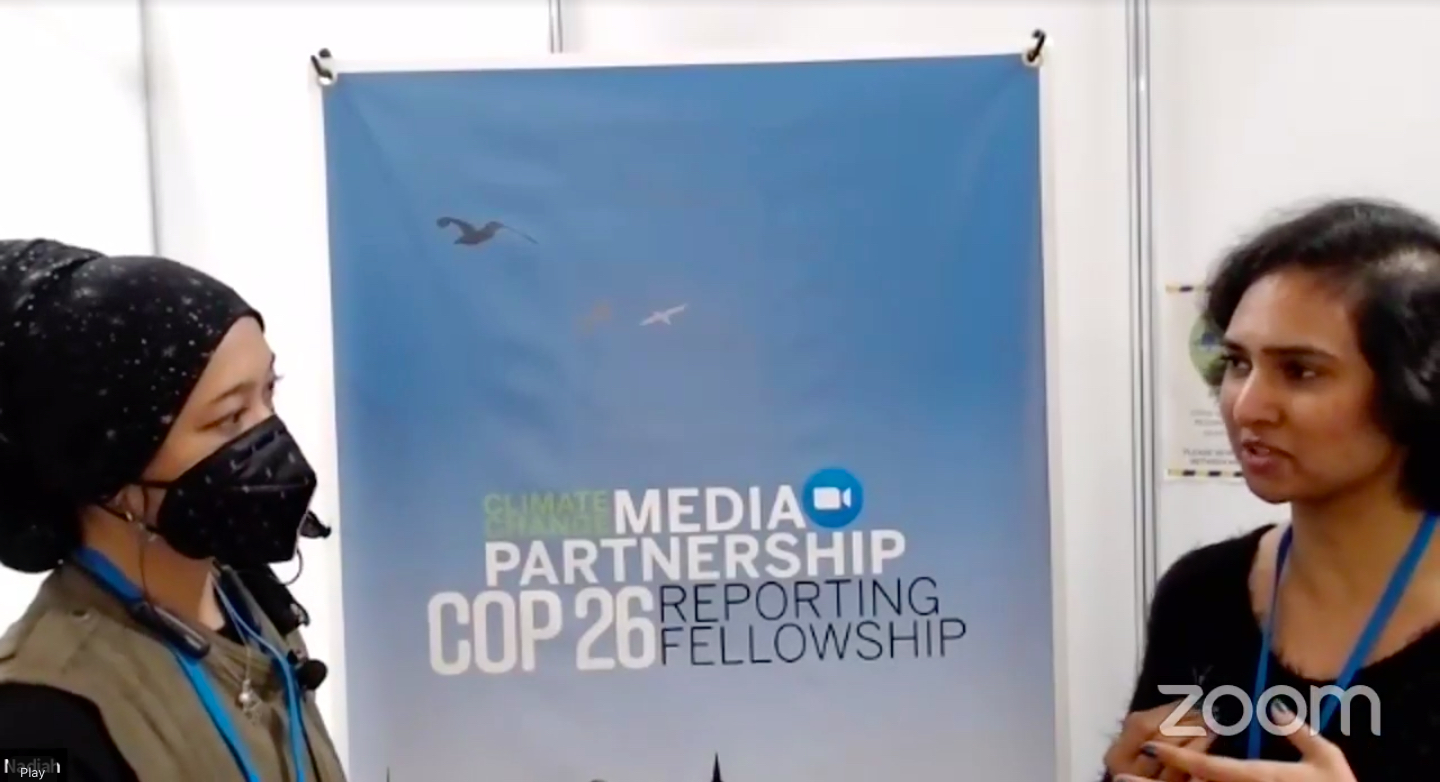

GLASGOW — At 2pm UK time on Monday, shortly before Barack Obama took the stage at the COP26 climate summit for a speech that was beamed around the world, an organization called the Earth Journalism Network started a live broadcast of its own from its makeshift, white-paneled cubicle on the top floor of the conference’s media center. EJN, which was founded in 2004 to support environmental journalism in developing countries, organized and paid for more than twenty reporters from four continents to come to Glasgow alongside a number of staffers, one of whom, Nadiah Rosli, opened the broadcast. “It is critical for low- and middle-income countries to have the opportunity to report live from COP26,” Rosli said, “but of course, this year, it is a bit more difficult because of COVID-19 and also the travel restrictions, so this broadcast we hope will help journalists covering COP-26 remotely.” The broadcast focused on loss and damage caused by the climate crisis, a key—and historically marginalized—issue for many poorer nations that was Monday’s main theme at COP. Rosli asked Saleemul Huq, a Bangladeshi climate expert, how journalists ought to think about the topic. “There’s a lot of non-economic costs,” Huq said. “Loss of cultures. Loss of temples and graveyards of people’s families.”

EJN—which is itself a project of Internews, an international media nonprofit—selected the journalists it brought to Glasgow in partnership with the Stanley Center for Peace and Security, a foundation based in Iowa. Around four hundred people applied for the fellowship; the reporters who were selected collectively represent news organizations in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tunisia, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Brazil, and Colombia. James Fahn—EJN’s executive director, who himself covered the second COP on a fellowship while working for a newspaper in Thailand in 1996—told me that his organization began taking reporters to climate conferences starting with the 2007 COP, in Indonesia. The logistics, he said, are always complicated, but the pandemic piled on additional challenges this year. Almost all of the journalists selected were already vaccinated and at least one was able to take up the British government’s offer (which has broadly had mixed success, at best) to send vaccines to COP delegates, but Fahn and his colleagues still had to reckon with the UK’s ever-shifting “red list” of countries, visitors from which would be required to quarantine in a hotel. “There’s a lot of risk involved,” Fahn said. “We don’t want people getting sick.”

Previously at COP26: Inside the biggest story in the world

Early last month, British officials took nearly fifty countries off the red list, with the seven that remained, including Colombia, scratched three weeks after that. María Mónica Monsalve, an EJN fellow who covers climate for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador, was checking in at the airport when the latter announcement was made, but it took effect too late to save her, and she spent the next five days in a London hotel room with a window that didn’t open. (She was occasionally permitted fifteen minutes of fresh air under strict supervision; after her quarantine ended, she got straight on a train crammed with unmasked passengers.) Monsalve covered the first days of COP, when world leaders including Colombian President Iván Duque showed up, from her hotel room; when she finally got into the venue, she found it a challenge to know where to look amid the hustle and bustle and technical talks, but was able to ask for help from EJN staffers who have covered COPs before. “I’m really glad my first COP was with this fellowship, because COPs are crazy,” she told me. “Otherwise, I think I would be crying in a corner.” She’s since covered stories around gender and access to the event, with activists blasting COP26 as historically exclusionary. “This is kind of personal because I had to quarantine,” she said.

Throughout the conference, The Scotsman newspaper has been publishing stories that the EJN journalists have written, billing them as “reports from the frontline of climate change.” One was a dispatch by Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi for the Peoples Gazette, a Nigerian news site, about multinational corporations’ practice of gas flaring in the Niger Delta region, where she grew up and still lives. Kevin-Alerechi told me that she got hooked on journalism as a kid, when her dad would make her watch CNN and Nigeria’s NTA network. (She didn’t always want to change the channel, she said, “but each time I watched people talking on TV, it captured my interest.”) She worked in radio before jumping to the Gazette when it launched last year, covering a regional beat to which climate is central. She’s written four stories from COP so far while also continuing to work on an investigation about devastating recent flooding in Nigeria. When I asked if her perspective on the climate crisis differs from that of a typical Western journalist, she said it doesn’t really. The flooding, she said, is “similar to what is happening around the world.”

Kevin-Alerechi said that being at COP has given her an opportunity to connect with journalists and activists from across Western Africa while also holding power to account. “Sometimes, when you go to communities, they will ask you, what is the international community doing about our issues?” she said, noting that at COP, she can put their questions directly to international power brokers. She’s also tried to chase down Nigerian officials; they’ve so far given her the runaround, but she reckons her odds of speaking to them at COP are better than at home, and she intends to keep trying. (In its short existence, Peoples Gazette has already faced official legal threats and web blockages.) Sim Kok Eng Amy, EJN’s Asia-Pacific program manager, told me that some of its journalists at COP have close relationships with their home country’s delegation; others don’t, but are at least able to corner officials at public-facing events, to “remind them of who they are here for.” Delegates’ negotiations, of course, are only one part of COP—indeed, many of the most interesting stories to come out of the conference so far have focused on activists and others in civil society, who actively want media attention. Being present on the ground, Monsalve said, “you get to see the whole picture, not only the official side of it.”

On Monday, during EJN’s live broadcast, Rosli spoke with another one of its journalist fellows: Rishika Pardikar, an independent journalist who has been covering the conference for The Wire, an Indian news site. As Pardikar started to speak, the background hum of journalists in neighboring cubicles (Bloomberg to the left of them, Reuters to the right) gave way to Obama’s speech blaring out from speakers in the media center. It wasn’t really audible to those watching the EJN broadcast over Facebook or Zoom, fortunately; still, sitting only a few feet away in EJN’s cubicle, I had to lean in to hear Pardikar talk about covering COP. “The way things have been going in terms of outcomes, or lack of outcomes, is not surprising to me, because many people have told me before that this is how it works,” Pardikar said. “But what I have been surprised by is how much happens here—and how much you can learn just by observation.”

Other notable stories, by Mathew Ingram:

- Employees of the Kyiv Post, the main English-language newspaper in Ukraine, were told when they came to work on Monday that they were all fired and the newspaper is shutting down, according to a report from Illia Ponomarenko, the paper’s defense reporter. A statement written by the Post‘s newsroom staff said that Adnan Kivan, the wealthy businessman who bought the paper in 2018, planned to start up a Ukrainian-language paper under the same brand name, and had hired an editor to oversee it, something existing staff saw as “an attempt to infringe on our editorial independence.” In retaliation, they said, Kivan fired all the paper’s editors and reporters, and now has plans to restart the paper with all new employees. “We see this as the owner getting rid of inconvenient, fair, and honest journalists,” the statement said.

- Journalists at Wirecutter, the product-review site owned by the New York Times, plan to go on strike during the site’s peak traffic period on Black Friday, according to a report from Bloomberg on Monday. “Over ninety percent of Wirecutter union members have voted to authorize a work stoppage lasting one or more days in late November, according to the NewsGuild,” the news site reported. The NewsGuild represents around 1,300 other editorial and business workers at the Times, and gained the right to represent staffers at Wirecutter two years ago. Black Friday, which is typically one of the biggest shopping days of the year, occurs the day after the Thanksgiving holiday; this year, it falls on November 26. “We know what we’re worth,” Wirecutter writer Katie Okamoto said. “We feel that it’s appropriate for us to, if we have to, demonstrate how worth it we are.”

- In the current environment of “political turmoil, economic change and a pandemic-driven focus on how we work,” labor has become a hot news beat, writes Ben Smith, media columnist for the Times. One sign of the increase in interest, he says, is the attention being paid to The Chief-Leader, a broadsheet founded for firefighters in 1897 that has covered the public service in New York ever since. Ben August, an entrepreneur who sold his human resources business, bought the paper this summer from the family who had owned it for more than a century, and says he wants to “transform it into a national voice of public and private-sector labor,” Smith writes. Meanwhile, Vice noted that this is the fourth time Smith has written about the NewsGuild without mentioning that he opposed the unionization of the BuzzFeed newsroom—which was represented by the NewsGuild—when he was the editor-in-chief there, before he joined the Times.

- Eoin Higgins, an investigative reporter who writes a newsletter called The Flashpoint, says management of the Guardian newspaper in the UK tried to intimidate him after he reported on episodes of transphobic behavior by certain members of the paper’s newsroom. “The Guardian’s Director of Editorial Legal Services Gill Phillips just contacted me this morning to demand a retraction,” Higgins reported on November 5. “That’s not going to happen. I stand by my reporting. Laws in the UK on defamation and libel are quite strict. It’s very easy to silence critical voices through the country’s legal system. But I’m based in the US, so these veiled British threats mean nothing.” Higgins said the paper accused him of defamation for noting that workers at the paper “described lead opinion writer Susanna Rustin as a ‘militant and obsessive anti-trans activist.’”

- Emilie Friedlander writes for Vice about a new cryptocurrency-based writing platform called Mirror, which used to hold an online popularity contest to determine who would get access to the platform, but recently opened up its services to everyone. “On one level, Mirror is a simple blogging platform like Substack or Medium. But it also offers an ever-expanding suite of crowdfunding tools made possible by blockchain technology that pushes the act of raising money on the Internet into psychedelic new shapes,” she writes. “Through Crowdfunds, a writer can issue financial backers a custom token that gives them fractional ownership of an essay—and a future cut of the proceeds if the writer decides to auction it off as an NFT.” Some writers have raised tens of thousands of dollars to finance their writing, Friedlander says.

- The Collaborative on Media & Messaging for Health and Social Policy—a project that is affiliated with Wesleyan University in Connecticut, the University of Minnesota, and Cornell University—has launched a new website it says is designed to help explore the question of how journalists can build healthy and equitable communities. The site features a resource library that collects research work relevant to media and messaging for health policy, and the group of institutions says that this “body of evidence can provide a road map for shifting opinions and changing narratives to advance health equity, while identifying potential obstacles and pitfalls to avoid along the way.” The resource library is searchable by focus area, research methodology, type of media, and specific topics, the collaborative project said in a statement.

- McClatchy says that since last month, it has been experimenting with a service that allows readers to play auto-generated audio versions of its news stories by clicking on a widget on the story page. The publisher of newspapers such as the Sacramento Bee and the Miami Herald said that clickthrough rates on the audio player have ranged from one to five percent across all of its news pages, depending on the length of the story and the section of the paper they’re in, according to a report in Digiday. Last month, the McClatchy sales team ran its first advertising campaign based on the audio feature, which included both pre-roll and mid-roll spots. The paper said that about seventy-five percent of readers completed the mid-roll ads, and almost one hundred percent of the pre-roll ads.

ICYMI: McClatchy to decline future Report for America participation, following hedge-fund critiques