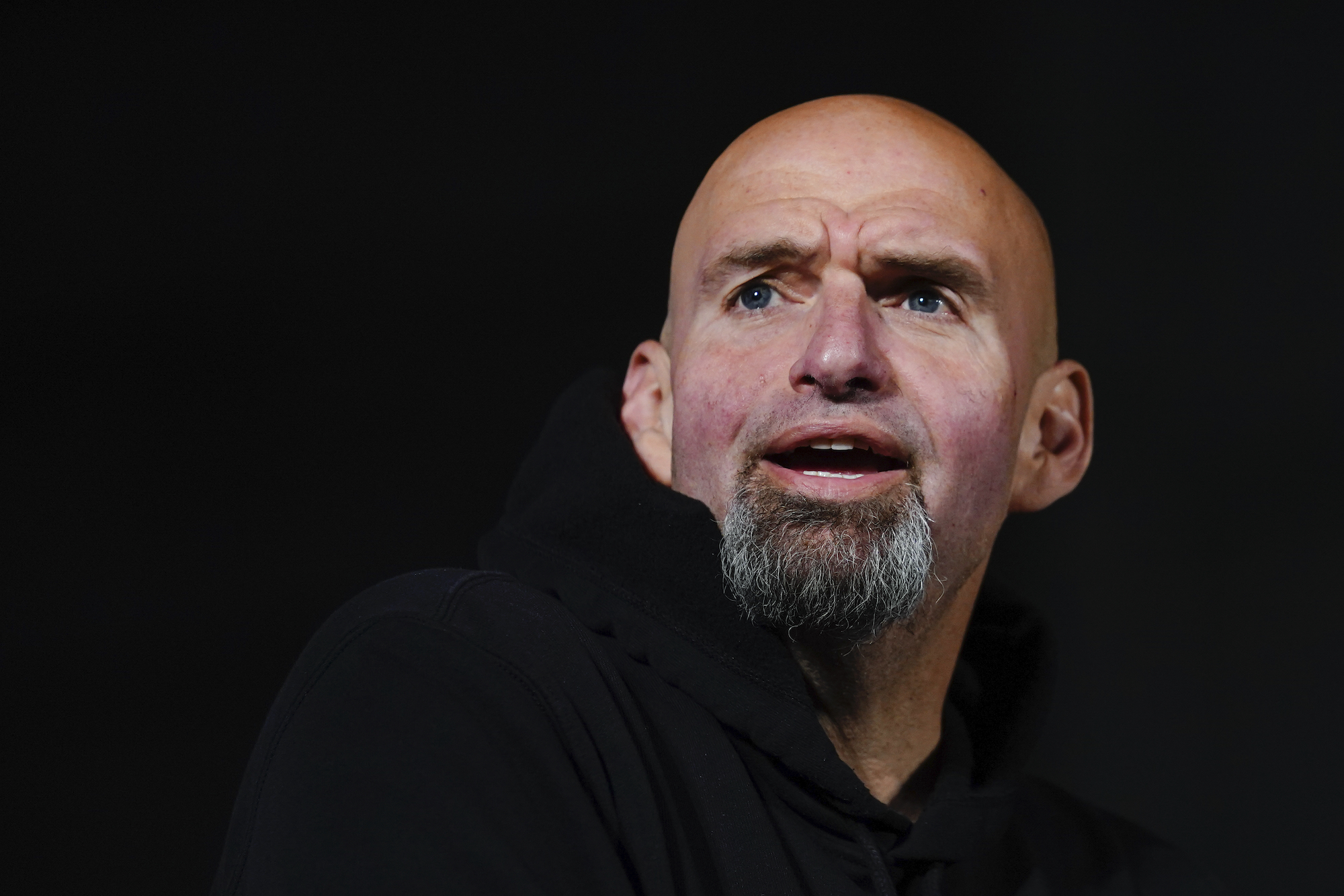

A week ago, New York magazine dropped a cover with a simple yet striking image: a close-up shot of John Fetterman, the hulking, goateed Democratic nominee for US Senate in Pennsylvania, staring straight forward, his brow slightly furrowed, alongside the headline “The Vulnerability of John Fetterman.” The cover accompanied an in-depth profile by Rebecca Traister, who landed perhaps the highest-profile interview with Fetterman since he had a major stroke just days before the Pennsylvania primary in May; they spoke over Google Meet, with Fetterman using closed-captioning technology to read Traister’s questions due to his ongoing difficulties with auditory processing. “As summer turned to fall, Fetterman returned to the trail in person, powering through his convalescence at rallies and via television and newspaper interviews, his physical condition visibly improving,” Traister wrote. “But what gained more traction in September and October in both the right-wing multiverse and the mainstream political press were” Republican attacks suggesting that Fetterman “was weak, both physically and in his approach to crime”—and that, when it came to his health, he was still hiding something.

Traister’s interview made a splash—but not as much as a different Fetterman interview that also came out last week: his first in-person TV sit-down since his stroke, with NBC’s Dasha Burns. The full interview lasted more than half an hour, but only a three-minute cut made its way onto NBC’s Nightly News, where Lester Holt introduced the sit-down as “not a typical candidate interview” and then threw to Burns, who noted that Fetterman had “required” closed captioning for the interview, then claimed that, “in small talk before the interview, without captioning, it wasn’t clear he was understanding our conversation.” There followed clips showing Fetterman pausing to read a question about his fitness for office from a monitor and tripping over the word “empathetic” (“That’s an example of the stroke,” Fetterman said, of the stumble), before Burns was shown asking Fetterman why he hasn’t released his medical records or made his physician available for an interview. (Fetterman’s campaign did publish a doctor’s letter back in June.) The final minute of the Nightly News package flashed up a Republican attack ad as a prelude to Burns asking Fetterman whether he’s “soft on crime,” before the conversation turned, for twenty seconds or so, to abortion. “Dr. Oz likes to make fun of me that I might miss a word,” Fetterman said (referring to his opponent, the TV doctor turned Republican politician Mehmet Oz), “but he’s missed two words, and that is ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on the national abortion ban.”

ICYMI: War coverage escalates, and goes back to the beginning

The interview—and, in particular, Burns’s contention that Fetterman seemed not to understand what she was saying without closed captioning—quickly drew criticism, including from Traister, who insisted, having herself interviewed Fetterman, that while his auditory processing is impaired, his comprehension, a very different faculty, is not; Kara Swisher, who also recently interviewed Fetterman and is herself a stroke survivor, was more scathing, referring to Burns’s comment as “nonsense” and suggesting that she might just be “bad at small talk.” Various prominent advocates for people with disabilities also pushed back on the fact that the interview was framed around Fetterman’s condition, describing it as “ableist,” a charge also leveled by Gisele Barreto Fetterman, Fetterman’s wife. “Recovering from a stroke in public isn’t easy,” Fetterman himself tweeted. “But in January, I’m going to be much better—and Dr. Oz will still be a fraud.” Oz, for his part, signal-boosted Burns’s question about Fetterman’s perceived lack of transparency, while other Republican campaign accounts amplified her “small talk” comment. Tucker Carlson did likewise on his Fox show. “What she just told you is that before the machine was turned on, John Fetterman could not understand human language,” Carlson said, musing aloud as to “where the man ends and the machine begins.”

Burns, for her part, clarified in subsequent appearances on MSNBC that she’d spoken to stroke experts who had told her that Fetterman’s reliance on closed captioning does not indicate “any sort of cognitive impairment”—but she also reiterated her claim that Fetterman had seemed not to “understand” what she was saying, and she otherwise defended her interview, stating, in response to Swisher, that different journalists can have different experiences with a candidate, and that all she could do was report on hers. “Our reporting did not and should not comment on fitness for office. This is for voters to decide,” Burns added on Twitter. “What we do push for as reporters is transparency. It’s our job.” (Burns also sat for an interview with Oz last week, pressing him as to why, as a medical doctor, he’d allowed his campaign to make light of Fetterman’s stroke.)

While Burns’s interview kicked off the media furor around Fetterman’s condition last week, it did not do so in isolation—right-wing media figures, in particular, have been questioning Fetterman’s health for weeks, and mainstream reporters and pundits seemed eager to weigh in on Burns’s interview with thoughts of their own. Sanjay Gupta, a doctor and CNN’s chief medical correspondent, assessed Fetterman’s apparent condition on air while pointing to colored zones on a plastic brain. Jonathan Martin, recently of the New York Times, called the Burns interview “rough” for Fetterman on the grounds that it would “only fuel questions about his health,” while Ed O’Keefe, of CBS, asked whether Pennsylvania voters are “comfortable with someone representing them who had to conduct a TV interview this way.” Back in the NBC Extended Universe, Joe Scarborough, of Morning Joe, slammed Burns’s critics as “idiots” and accused them of behaving like Trump supporters; on the same show, Chris Matthews—lesser-spotted since he timed out of his own MSNBC show in 2020, amid allegations of sexist conduct—described Burns’s questions as “soft” and “reasonable” before referring to Fetterman as “a guy who cannot answer the question because he had to look at the monitor.” (In fact, he used the monitor to answer Burns’s questions.) A newsletter from NBC’s Meet the Press, meanwhile, led with the headline “Fetterman, Walker face political challenges outside of the overall environment”—equating Fetterman’s health, at least in terms of political liability, with allegations that Herschel Walker, the anti-abortion Republican Senate candidate in Georgia, paid a woman to have an abortion.

The Fetterman furor was strange, in one sense, since there should have been nothing unexpected in Fetterman using closed captioning in an interview; he’s done so repeatedly since returning to the campaign trail, and been very open about it, as Traister pointed out on The Ringer’s Press Box podcast last week. (NBC made a “basic accommodation” for Fetterman’s health sound like an investigative finding, Traister said.) That said, there’s also nothing unexpected in the media homing in on the cognitive functioning of a prominent politician—that increasingly seems to be a favored pastime, especially of commentators on the right, but also of liberal pundits and the objective journalism crowd who position themselves in between. Often, such coverage is tied to another hot-button topic in US political discourse right now: advanced age. (Indeed, for her previous major profile, Traister wrote about the eighty-nine-year-old Democratic senator Dianne Feinstein, reporting primarily on her political record but also on the fact that she appears “mentally compromised.”) The age debate often revolves around President Biden, and last week was no exception. Politico ran a story on his upcoming eightieth birthday, writing that it “will likely intensify scrutiny of Biden’s health” and decision as to whether he will run for reelection. CNN’s Jake Tapper, meanwhile, scored a rare sit-down interview with Biden and asked him to respond to concerns about his age. (Biden responded by telling Tapper to “look what I’ve gotten done.”)

Two years ago this month, with Donald Trump in the hospital following his diagnosis with covid, Ben Smith, then the media columnist at the Times, wrote about the increasing urgency of working out how to cover the condition of America’s elderly leaders at a time when there are so many of them, concluding that, while journalists have often seen a politician’s age as the sort of thing one doesn’t talk about, the US needs “a reporting culture that’s ready to handle the public decline of this generation of leaders as long as they insist on declining in public,” and that “searching questions about everything from sleep to cognition shouldn’t be off limits.” Smith was right, and yet, as he also acknowledged, such stories aren’t easy; they must, ultimately, be told with care and sensitivity. Cultural squeamishness around covering the age of our leaders can be an impediment to needed scrutiny—but the heightened level of attention that often accompanies such stories can also incentivize journalists to tell them compassionately and to ensure that they are based on solid evidence, not just idle political gossip. In return, it’s reasonable for reporters to expect at least some degree of medical transparency from aging people with immense power. (Trump’s medical team infamously failed this expectation following his covid hospitalization.)

Coverage of a politician like Fetterman doesn’t revolve around age, of course (he’s fifty-three), and in some ways, age and disability in politics demand very different coverage frames—the former, for instance, raises questions of generational representation that are separate from individual health concerns. Still, some of the same issues apply here: around transparency, yes (and reasonable observers can probably disagree as to how much is enough in Fetterman’s case), but also, on the media’s end, around sensitivity and compassion—and a recognition that while a politician’s condition is a story, it’s rarely the only story worth telling about them. (Again, Traister did a good job of holding Feinstein accountable for her worldview and policies while also reporting on her mental acuity.) NBC’s Fetterman interview, at least as it was packaged for the Nightly News, failed on these terms. It presented Fetterman’s condition as the key takeaway from the interview without ever justifying why it should be seen as such, failing, among other things, to add prominent medical context as to what viewers might expect to see from a stroke survivor at Fetterman’s stage of recovery, and using language loosely. Again, understanding and auditory processing are not interchangeable concepts.

Even if it wasn’t Burns’s intention, the framing of her interview implicitly did comment on Fetterman’s fitness for office, by presenting a reasonable and normal accessibility accommodation for people with his condition as sufficiently abnormal to merit top-takeaway treatment. (If Fetterman had worn eyeglasses for the interview, Burns would not have remarked that he couldn’t seem to see her until he put them on.) It’s true that it’s rare to see a candidate for major office using closed captioning in an interview, and that Burns didn’t state any conclusions about Fetterman’s fitness. But the framing choices we make do influence how people vote, and it’s never good enough to pretend that we have no power over news consumers’ perceptions, even if we can’t control how the Tucker Carlsons of the world twist our words. This is particularly true when it comes to basic questions of accommodating disabilities in politics. If Fetterman is unusual as a political candidate using closed captioning, the most pertinent question we can ask is why. The fact that this was “not a typical candidate interview” says much more about who gets to be a political candidate in America than it does about John Fetterman.

In political journalism, “vulnerability” usually carries a negative connotation—referring to political Achilles’ heels in a world that rewards strength and toughness. In her recent profile, Traister interrogated a very different meaning of the same word, asking whether Fetterman—once a cartoonish avatar of political strength-projection—might have conjured a new type of political appeal out of his stroke and subsequent condition. “Voters have been knocked flat by a pandemic, by Dobbs, by storms and mass shootings and rising prices—by reckoning with it all,” Traister wrote. “The vision of a human being who has also been knocked flat making his way back toward health along an unlikely and precarious path is very powerful.”

Below, more on representation and the Pennsylvania Senate race:

- Representation, I: For Teen Vogue, Sarah Blahovec, a disability community organizer and consultant, writes that NBC’s Fetterman interview unleashed a wave of ableist discourse that has been “deeply disappointing and speaks to why so few people with disabilities run for—or win—elected office.” Disabled people are underrepresented in politics, though not enough data is available to determine the precise extent of the problem, Blahovec writes. “Disabled people know their behaviors and actions will be heavily scrutinized by the press or even become the story rather than the policies they’re fighting for. They know that their required accommodations will be seen as a big deal rather than something perfectly reasonable that many people use in their daily lives.”

- Representation, II: For the Times, David M. Perry, a journalist and historian who regularly writes about disability, criticized Burns for “implying that NBC was doing Mr. Fetterman a favor by using captioning,” before charting the long history of stigma around disability in US politics and media coverage thereof; FDR, for example, “tried to keep the press from photographing him being transferred into and out of his wheelchair.” Today, “politicians as diverse as Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas, Senator Tammy Duckworth of Illinois and Representative Madison Cawthorn of North Carolina use wheelchairs, and even their most virulent political opponents generally don’t bring up their disabilities,” Perry writes. “But when it comes to invisible disabilities, and in particular ones that involve communication or mental function, stigma is trickier to detect and dispel.”

- The race, I: Rolling Stone’s Kara Voght profiled Gisele Barreto Fetterman, who has become a “political star” after her husband’s stroke forced her into the limelight. “As a former undocumented immigrant from Brazil, standing in the spotlight runs counter to years of warnings her mother gave her to ‘be invisible,’” but Gisele has “found herself not just surviving in uncertainty, but thriving,” Voght writes. The media response to the NBC interview and the broader questions around Fetterman’s condition have “cast Gisele into yet another role: defending her husband against attacks she views as ableist.”

- The race, II: Another interview Fetterman did last week was with the editorial board of PennLive, a local news outlet, as he sought the board’s endorsement. (I wrote about the status of the newspaper endorsement in a newsletter last week.) Oz did not respond to a request that he also sit for an endorsement interview. “I had a stroke, and I showed up,” Fetterman wrote on Twitter. “What’s your excuse Dr. Oz?”

Other notable stories:

- In an essay adapted from her new memoir, Newsroom Confidential, Margaret Sullivan, the former media critic at the Post, called on members of the press not to cover Trump as they did in 2016 if he runs again in 2024. “Journalists—specifically those who cover politics—must keep a sharp focus on truth-seeking, not old-style performative neutrality,” Sullivan writes. Meanwhile, the New Republic’s Jacob Bacharach asks whether Sullivan should have been even tougher on the media in her book; Sullivan is “a fierce critic,” he writes, and her book is “never boring,” but “one nevertheless senses a hesitance to burn certain bridges, and I couldn’t put down the suspicion that some punches were pulled.”

- In 2013, Rupert Murdoch split his media empire in two, putting its TV and entertainment assets under the “Fox Corp” umbrella and its publishing assets under the “News Corp” umbrella. Since then, Fox Corp has sold most of its entertainment properties to Disney, while News Corp has outperformed expectations. Now, the Wall Street Journal’s Cara Lombardo, Dana Cimilluca, and Jeffrey A. Trachtenberg report, Murdoch is weighing bringing Fox Corp and News Corp back under the same roof—a move that would be similar, in some ways, to the 2019 re-merger of Viacom and CBS (now Paramount).

- In August, the union that represents staffers at the Times published an analysis finding that employees of color have been significantly less likely to get strong performance ratings than their white counterparts. Over the weekend, Marc Lacey, a managing editor at the Times, told a roundtable organized by Journal-isms that he and other top editors have acknowledged that there is a “problem” with the paper’s performance-evaluation system and are working to “overhaul” it. (CJR’s Feven Merid profiled Lacey last year.)

- On Friday, two brothers in Malta pleaded not guilty to the murder of the investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017—then reversed course and pleaded guilty. A judge sentenced them to forty years in prison; a wealthy businessman who stands accused of ordering the murder is still awaiting trial. Yesterday, demonstrators gathered in Malta to demand justice for Caruana Galizia on the fifth anniversary of her death.

- A judge in El Salvador ordered the arrests of several high-ranking former military officials on suspicion of complicity in the 1982 murders of Jan Kuiper, Koos Koster, Hans ter Laag, and Joop Willemsen—four TV journalists from the Netherlands who were in El Salvador covering a leftist rebel movement in the country’s civil war. One of the officials now resides in the US and faces extradition. The AP’s Marcos Alemán has more.

- The Observer’s Deepa Parent has an update on the crackdown on press freedom in Iran, where more than forty journalists have now been arrested since the death of a young woman in police custody sparked mass protests. (CJR’s Merid wrote about the crackdown two weeks ago.) Over the weekend, a significant fire broke out at the notorious Evin prison, in Tehran, which has often been used to hold detained journalists.

- Also for The Observer, Shanti Das reports on the “sweeping restrictions” that photojournalists and broadcasters could face in their coverage of the upcoming soccer World Cup in Qatar, which has moved to ban recording at a range of locations including private businesses and residences. The prohibitions will make it harder for visual journalists to cover non-sports stories, including the mistreatment of migrant workers.

- And Betsy Morais, CJR’s managing editor, spoke with John Bennet—a longtime former editor at The New Yorker, with whom Morais worked and became close friends—shortly before he died of cancer earlier this year, recording his thoughts on his life, career, and approach to his work for a podcast that also features the voices of some of the writers whose copy Bennet edited. You can listen to the podcast and read more here.

Listen: How John Bennet went from East Texas kid to New Yorker editor

Jon Allsop is a freelance journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Review of Books, Foreign Policy, and The Nation, among other outlets. He writes CJR’s newsletter The Media Today. Find him on Twitter @Jon_Allsop.