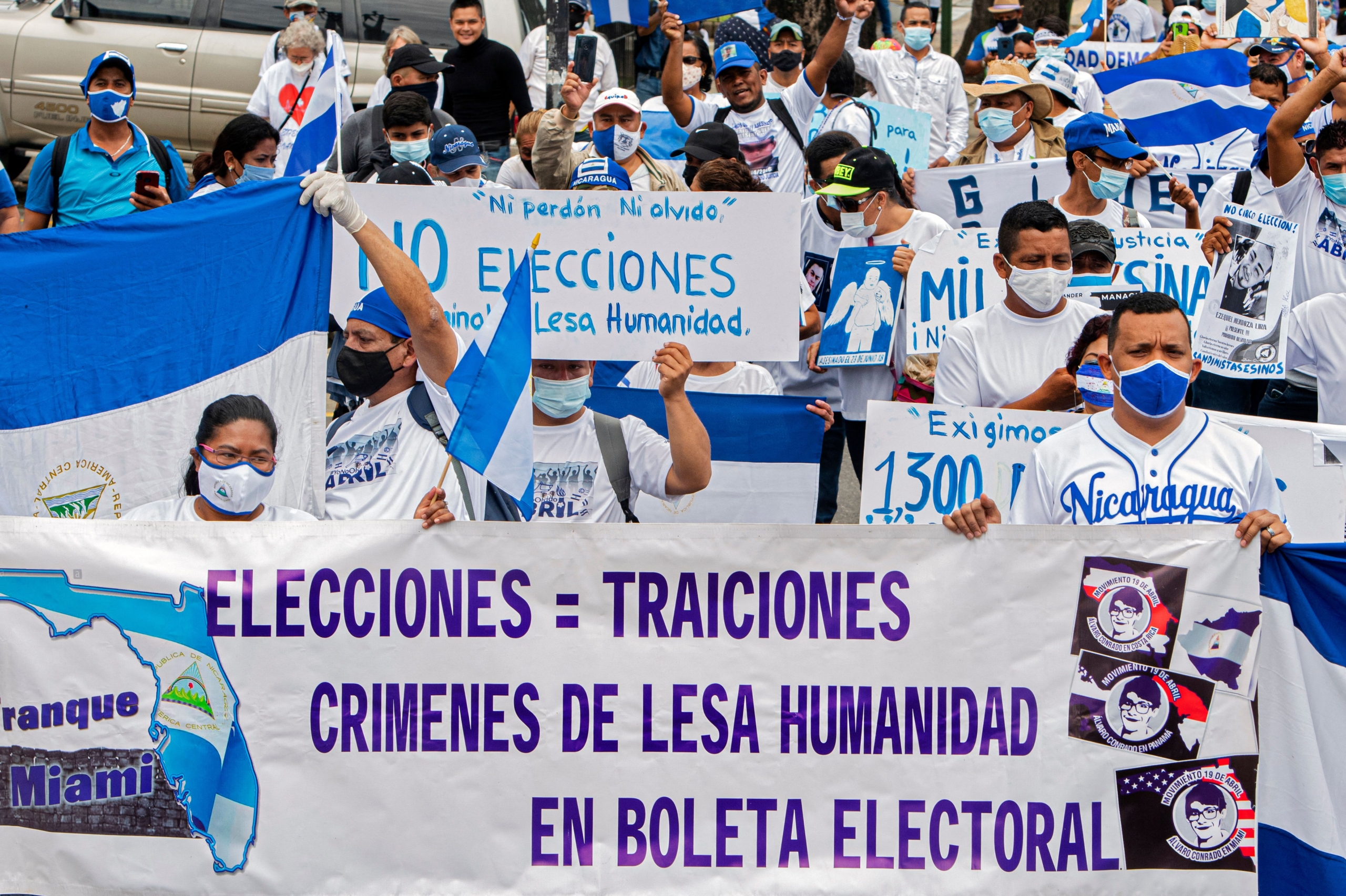

In 2018, tens of thousands of Nicaraguans flooded the streets to protest against the nation’s increasingly repressive president, Daniel Ortega, and his wife Rosario Murillo, who holds an amalgam of positions, including vice president and communications coordinator. The protests posed a serious threat to Ortega’s fourteen-year hold on power; with news outlets doggedly covering the country’s biggest story, the Ortega regime blockaded print materials needed to run newspapers, ransacked newsrooms, and arrested and tortured some journalists. Since then, the administration has continued its brutal crackdown on independent journalism, as Oswaldo Rivas documented for CJR earlier this year. In November, Ortega will be up for reelection; with a number of former journalists running against him, one could argue that the fate of Nicaragua’s free press is also on the ballot.

This summer has seen the Ortega administration grow increasingly brazen in its attacks on journalism. In late May, police officers raided and ransacked several newsrooms, detained some of their staffers, and launched sham investigations into prominent journalists and opposition leaders. By early June, favored opposition candidate Cristiana Chamorro––a popular journalist and the daughter of a former Nicaraguan president (who beat Ortega for the office in 1990)––was placed on house arrest, where she remains, under dubious money-laundering charges. Throughout the summer, the Ortega regime arrested six more presidential candidates—including Miguel Mora, another journalist—under similar pretenses.

Since then, dozens of journalists have been summoned for questioning related to these investigations. “There is an attempt to turn the exercise of journalism into a crime, by defining what is a lie,” Fabian Medina, a columnist for La Prensa, told PEN International, a press freedom group, in June. In July, Reporters Without Borders, another press freedom group, added Ortega to their “predators gallery,” with the likes of Mohammed bin Salman, Viktor Orbán, and Kim Jong-Un.

At least twenty-six journalists have gone into exile between June and August. Two weeks ago, a report in La Prensa, a prominent independent newspaper in Nicaragua, documented eighty attacks on press freedom in the month of August alone; seventy-eight, it said, were carried out by “state agents.” One of those attacks included another raid on La Prensa, forcing it to shut print operations and leading to the arrest of its manager, Juan Lorenzo Holmann Chamorro. Last week, La Prensa––the last independent print newspaper in Nicaragua––laid off half its staff, in part, it said, to “guarantee the survival of the company in the midst of a hostile environment imposed on us by the dictatorship.” The newspaper added, “La Prensa will prevail to narrate the fall of Orteguismo.”

The country’s press-freedom dynamics are not unique in the region. In El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele has fostered hostilities toward the free press, with much of his ire trained on El Faro (“The Lighthouse”), a digital newsroom and an investigative powerhouse that has exposed countless wrongdoings in his administration. A report from earlier this month by the Association of Journalists of El Salvador documented 177 attacks against journalists this year, thirty-four of which were carried out by the National Civil Police. “From the highest authorities and from government spokespersons, guarantees of press freedom are being eroded,” Pedro Vaca, a press freedom advocate, told the LatAm Journalism Review.

In Cuba, since anti-government protests began in July, dozens of writers and artists have been imprisoned; cybersecurity laws proposed in August further threaten the livelihood of online dissent. In Guatemala, advocacy groups have warned about President Alejandro Giammattei’s anti-press rhetoric, particularly surrounding Covid. There, in July, Pedro Alfonso Guadrón Hernández, a local reporter, was shot and killed in a small town near the borders of Honduras and El Salvador; press advocates have drawn connections between his murder and his reporting on local corruption and drug trafficking.

Three Central American countries now rank among the lowest in the world in Article 19’s freedom of expression index. In Nicaragua and El Salvador, the decline has been rapid: Between 2010 and 2020, on the group’s hundred-point scale, Nicaragua dropped from 39 to 8, with much of its decline occurring since 2015, while El Salvador dropped from 80 to 57. As the report states: “Populist leaders and those who seek to entrench their own power hate accountability.”

Below, more on journalism in Latin America:

- “Under an avalanche of memories”: Among those under investigation in Nicaragua is Sergio Ramírez, an acclaimed novelist. Earlier this month, Ortega issued a warrant for his arrest––a familiar pattern in a country with a sordid history of jailing writers and intellectuals under the Somoza dictatorship. Though the two fought together in the Sandinista revolution, Ramírez’s latest novel, Tongelele No Sabía Bailar, recounts the country’s spin into dictatorship since 2018. Ortega has also ordered customs officers to impound copies of the book. Ramírez spoke to The Guardian from exile in Costa Rica.

- In better news: Ecuador is seeking to reform a restrictive communications law, enacted in 2013, that essentially imposed sanctions on news media. While some elected officials still favor the most restrictive parts of the law, Assemblymember Marjorie Chávez told the LatAm Journalism Review, “I believe [reform] is something that the country is waiting for, the change of model. And to stop waiting for the State to tell you what to consume, what kind of information to consume and under what conditions.”

Other notable stories:

- For CJR’s latest magazine, Shinhee Kang, Ian Karbal, and Feven Merid interviewed ten political journalists who began their careers in the Trump era. They discuss their relationships with news consumers, the ways they view journalistic objectivity, and how they see the future of political journalism.

- The Washington Post dove into how the disappearance of Gabby Petito became a social media sensation. The hashtag of her name has been viewed on TikTok more than 212 million times, the Post writes. The article adds, “People go missing every day, but few cases receive this kind of unwavering attention.” Last year, Alexandria Neason wrote for CJR on the disappearance of Vanessa Guillén: “The unsolved disappearance of Guillén is the story of Breonna Taylor is the story of Nina Pop is the story of Tony McDade. The details of each life and death differ in important ways, but the press is always a character, often making the wrong choices about focus and framing.”

- On Thursday, Win McCormack, the owner and editor in chief of The New Republic, endorsed Nick Kristof, a New York Times columnist on leave to make a run for governor of Oregon. (Or, as Defector put it: “Hack Meekly Endorses Hack.”) Earlier this month, Jon Allsop wrote about the porous boundaries between politics and media.

- In more gubernatorial news, apparently Beto O’Rourke is running for governor of Texas. Vanity Fair, do your thing.

- Ben Smith, the Times’s media columnist, spoke with Antony Blinken, the secretary of state, about the US’s botched evacuation of Afghan journalists. Blinken insisted that the government has done, and will continue to do, everything in its power to help Afghan journalists. However, those involved in the evacuations dispute his claim. “We didn’t see any policy here,” Joel Simon, head of the Committee to Protect Journalists, told Smith. “Our experience was that powerful media organizations were able to leverage their own relationships and use their own resources.”

This post has been updated to clarify a reference to Nick Kristof.

Savannah Jacobson is a contributor to CJR.