NPR last week announced its decision to shut down comments on its website in favor of comments on social media—saying “the audience itself has decided.” In a post explaining its decision, NPR’s ombudsman and public editor Elizabeth Jensen says only .06 percent of site users comment on the site. NPR guesses that the commenters on the NPR site are not representative of the demographic of their listenership. Conversations are, instead, being held on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media. Based on the cost of the system and the small fraction of users, maintaining comments just isn’t worth it for them—or even feasible.

NPR is only the latest news organization to close commenting systems in favor of social media. Yet, shutting down comments isn’t ideal. The moves also shutter some really positive aspects of commenting—mainly, the opportunity to connect with readers. There are dedicated commenters out there who could be a great resource for reporters, and whose contributions should be highlighted. But as it stands, among organizations that maintain comment sections, time is so devoured by dealing with negative comments and trolls that there’s little opportunity to tap into productive comments.

One group—The Coral Project, a collaboration between The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Mozilla Foundation, funded by a $3.89 million grant from the Knight Foundation (which also funds the Tow Center for Digital Journalism)—is developing open-source tools for newsrooms everywhere to cut through the negative trolls and tap into potential of audience engagement for journalism. Their vision is ambitious: to expand the realm of possibility for connecting with readers, and ultimately to give even small newsrooms an easy way to manage engagement—normally reserved for those who can pay for it.

“What is the comment box for?”

The Coral Project, its name inspired by the elegant filtering capabilities of coral in the ocean, started out as a collaboration between The New York Times and The Washington Post, who wanted to join forces to improve commenting, invite reader interaction, and expand our notions of audience engagement beyond comment moderation. The project aims to help publishers foster meaningful conversations with readers on their own sites.

Since The Coral Project was first announced two years ago, they have identified and are developing three highly customizable and open-source tools, as well as a guide to the tools and issues of audience engagement. I spoke with The Coral Project’s director, Andrew Losowsky, who told me, “This isn’t just, how do we build a better comment box? That doesn’t answer the bigger question of what is the comment box for? And what do we want?” The team spoke to more than 150 newsrooms in 30 countries to figure this out:

The conversation that we always start with, [is]: What is the role of audience in your journalistic mission? And what could the role of the audience be in your journalistic mission if you had the right tools? Some of them can answer the first, and almost no one can answer the second.

The reason for this, Losowsky says, “is because newsrooms haven’t had the luxury of being able to think about these things, especially not the people who work in engagement.”

The idea is that Coral’s tools will work with sites’ existing systems. Currently, most news organizations use free services like Disqus or paid ones like Adobe LiveFyre to host commenting on their sites. Disqus is often the most straightforward solution. It is a simple embed and uses a universal login for commenters across sites that use Disqus. It is not only free for news organizations to use but also a source of revenue (through sponsored ads). Disqus helps moderators by providing a “reputation” badge for each user—a vague, Disqus-wide classification that identifies high- and low-quality commenters. The downside is that Disqus controls all of its user information, Losowsky says, so that the publishing companies don’t know anything about their users over their whole site.

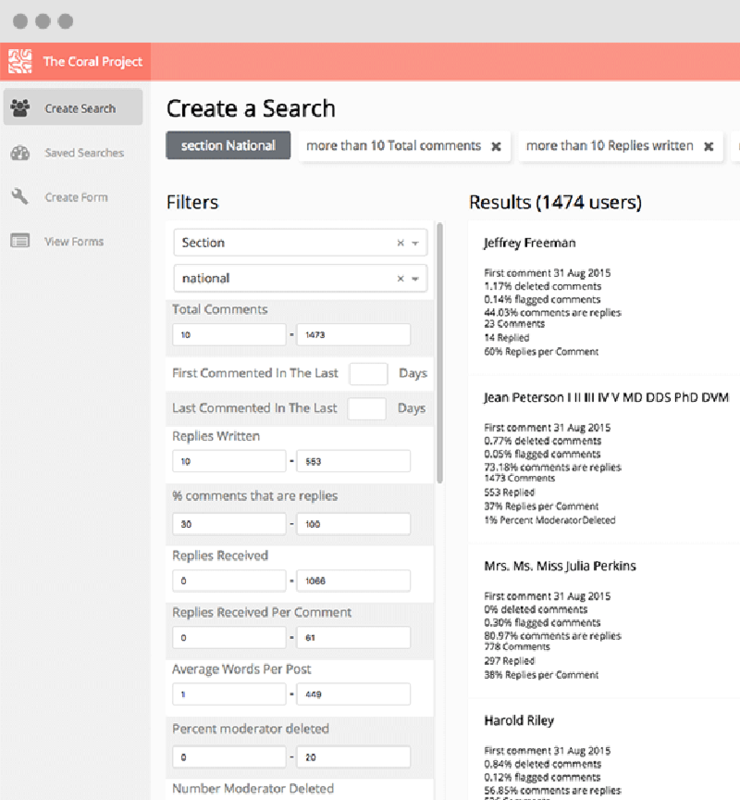

The Coral Project’s first tool, called Trust, will allow news organizations to access user data, and therefore enable them to find and identify the best commenters. Losowsky is “fairly confident” the Trust tool will be able to plug into Disqus, Adobe LiveFyre, and the rest. The Washington Post is currently testing a Trust beta, which Losowsky demoed for me. The interface looks like a database of every person who has ever commented on The Post. It is easy to manipulate the terms to very quickly create lists based on various parameters—the number of comments in any given section, a percent of comments flagged by moderators, highly rated comments, and so on.

A slice of a Trust prototype gives an idea of what the tool can do.

Trust is meant to “highlight the good as much as punish the bad,” says Losowsky. If, for example, you limit your search to commenters who have made at least 30 comments on the WaPo site, none of which have been removed by moderators and are all over 20 words long, you suddenly have a much shorter list of the best commenters. Then, you can set parameters so that these commenters bypass moderation and their comments are automatically featured. Commenters who tend to be flagged, on the other hand, can be sent straight to pre-moderation. Publishers can specify, down to the number of Tweets, the threshold at which they want to moderate.

Coral’s other tool, called Ask, is a basic, customizable survey aimed at curating conversation, not just moderating it. “We’re not going to have a good conversation around Donald Trump,” Losowsky points out. “So, instead, we’re going to ask you to tell a story, and then we publish the best answers. It…makes [the conversation] more controlled.”

The organization is in the process of developing another piece of software called Talk that is meant to look more like a typical comment-box system. It’s still in the early stages of production. The hope is The Coral Project’s tools will ultimately help connect reporters to sources and build networks with interested communities.

Connecting with readers

Even small changes can shape reader interaction and encourage positive engagement. That’s why Coral also hopes to educate users on how “the design of comments changes the kinds of interactions you have,” according to Losowsky. Community managers have already developed ways to work with the limited tools they do have to improve interactions.

I emailed with Lilah Raptopoulos, community manager at the Financial Times, about what successful audience engagement looks like. She is not officially affiliated with Coral, but she participated in some of Coral’s initial brainstorms.

She says engagement is most valuable when readers can be resources for reporters. She shares an example of how the FT dealt with a recent high-profile issue: Brexit. In general, she says,

For the months before the referendum, the comments in the stories on Brexit were overwhelmed with readers campaigning or arguing for Remain or Leave. Often they were repetitive, and not very illuminating, and sometimes personally insulting. But the minute the polls were closed, that campaigning and arguing stopped, and what emerged were thoughtful reflections on the weight of this decision, and thoughts about what was ahead….I sense that is what’s happening with the US election, too.

She highlights some of the strategies she used after the referendum:

The morning after the referendum vote, we picked up on a comment from a young FT reader named Nicholas Barrett on what he called, in the comment, “the three tragedies” of its outcome. I featured it as an editor’s pick…and added it to this comments hub, which I created specifically to curate and highlight the best user comments over that week….

At about noon, we realized that another FT reader had shared that same comment on Twitter that morning, and it quickly took on a life of its own, with 95k retweets and about 4 million impressions total.…So the question became, what can we do with this? We worked with the op-ed desk to commission a piece from Barrett….

In the first hour after Barrett’s’ piece was published, over 100 comments had accumulated, none of which were written from a millennial perspective—in fact, many were complaining that the UK’s younger voters hadn’t come out to vote. So I tried a prompt asking for young people’s thoughts. In the 24 hours that followed, dozens of unique millennial perspectives had accumulated, the tone improved, and conversations had taken off from them.

FT then created a follow-up story with a roundup of the best comments. Another tactic, she says, is to ask readers to contribute expertise: “One example is us asking legal expert readers to help us answer the tough questions on Brexit that still didn’t have answers a few days before the referendum.” FT developed a feature from those answers. While she didn’t use Coral in this example, Coral’s tools would aim to streamline such a process, making it easier for those without a community team to do similar work.

Featuring reader comments also has a positive effect on those readers’ future engagement. In June 2016, the Engaging News Project (which is partnering with The Coral Project to survey commenters) released a study of 9 million New York Times comments, assessing how the in-house Times redesign in November 2011 affected comments. Among other things, the redesign put comments directly below the article—previously, they had been on a separate page, linked at the bottom of articles. The study found that, in the year after the redesign, Times comments solicited fewer abuse flags—suggesting an improvement in the civility of discussion—and that having a comment featured by an editor led to a boost in commenting by that reader.

The Times has also de-threaded comments so they feel more like statements, which discourages argument threads, and has experimented with structured online comments to focus conversations. Using questions to prompt readers and help them formulate an opinion before typing is emerging as one of the best tools for focusing conversation. As Raptopoulos says, “If we find a way to structure the conversation with a question that sits up at the top of the comments, we can not only give people some guidance that really improves the quality, but we also speak to all these people who wouldn’t normally comment.”

Of course, every organization is different. Annemarie Dooling, who ran community at The Huffington Post (and worked with Losowsky there) and is now the director of programming at Racked.com, writes via email: “Racked is moving toward a distributed model, meaning that our most important stories will be in our newsletter in full, as well as having a presence on the site.…So even though we do have on-site comments, they are not a tentpole of our long-term plan because we’ve noticed reader behavior is to gravitate to our newsletter and then have private discussions.” The important thing, writes Dooling, is to tailor your work with an understanding of your audience:

No one should be writing a story just to write one. You always have an intention in mind. Maybe you want your reader to buy something, or contribute to a Kickstarter [project], or have a greater understanding of an issue, or send in a recipe….There’s no one end goal for all reader engagement.

“The largest problem with commenting is philosophical, not technical,” writes Dooling. News sites don’t think enough about what they’re trying to achieve through comments. Losowsky cites the same phenomenon, mentioning that comments were grandfathered in from original blog designs but that many organizations haven’t given thought to how they’re using them.

Meanwhile, news sites are craving “positive and constructive” reader input, as NPR’s Jensen writes in her post. They are looking for less reactionary reader comments, before the story gets written rather than after. NPR will be using Hearken to build audience engagement and solicit reader feedback.

Whether The Coral Project will be able to drive news sites away from shutting down their own commenting systems and encouraging discussion on social media instead is yet to be determined. But The Coral Project only provides the tools—how successful newsrooms are in connecting with readers has to do with the initiative that news organizations themselves take, whether they are proactive in building audiences or hand over commenting to social media platforms where they have little control.