Executive Summary

News organizations are meant to play a critical role in the dissemination of quality, accurate information in society. This has become more challenging with the onslaught of hoaxes, misinformation, and other forms of inaccurate content that flow constantly over digital platforms.

Journalists today have an imperative—and an opportunity—to sift through the mass of content being created and shared in order to separate true from false, and to help the truth to spread.

Unfortunately, as this paper details, that isn’t the current reality of how news organizations cover unverified claims, online rumors, and viral content. Lies spread much farther than the truth, and news organizations play a powerful role in making this happen.

News websites dedicate far more time and resources to propagating questionable and often false claims than they do working to verify and/or debunk viral content and online rumors. Rather than acting as a source of accurate information, online media frequently promote misinformation in an attempt to drive traffic and social engagement.

The above conclusions are the result of several months spent gathering and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data about how news organizations cover unverified claims and work to debunk false online information. This included interviews with journalists and other practitioners, a review of relevant scientific literature, and the analysis of over 1,500 news articles about more than 100 online rumors that circulated in the online press between August and December of 2014.

Many of the trends and findings detailed in the paper reflect poorly on how online media behave. Journalists have always sought out emerging (and often unverified) news. They have always followed-on the reports of other news organizations. But today the bar for what is worth giving attention seems to be much lower. There are also widely used practices in online news that are misleading and confusing to the public. These practices reflect short-term thinking that ultimately fails to deliver the full value of a piece of emerging news.

What are these bad practices? Key findings include:

- Many news sites apply little or no basic verification to the claims they pass on. Instead, they rely on linking-out to other media reports, which themselves often only cite other media reports as well. The story’s point of origin, once traced back through the chain of links, is often something posted on social media or a thinly sourced claim from a person or entity.

- Among other problems, this lack of verification makes journalists easy marks for hoaxsters and others who seek to gain credibility and traffic by getting the press to cite their claims and content.

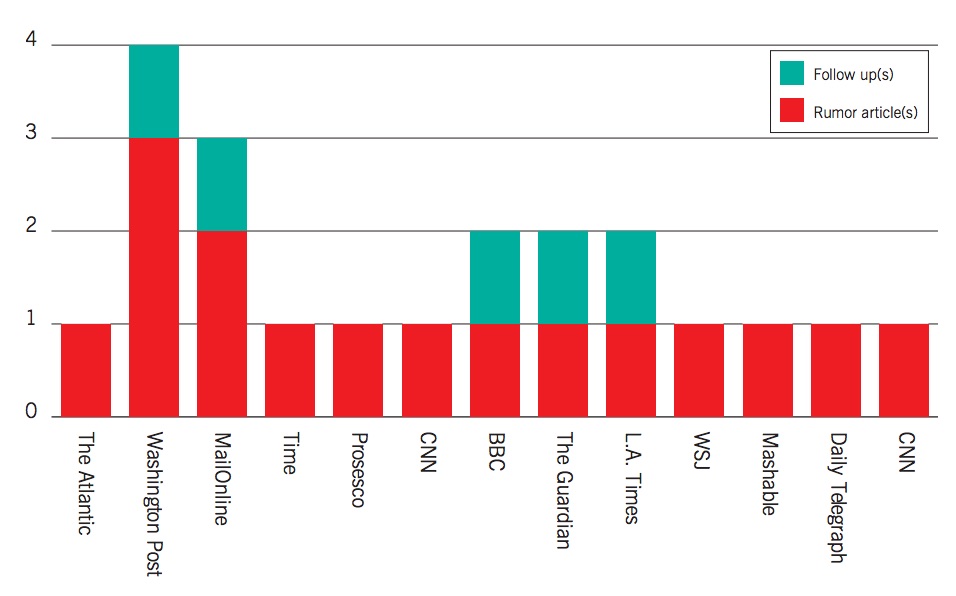

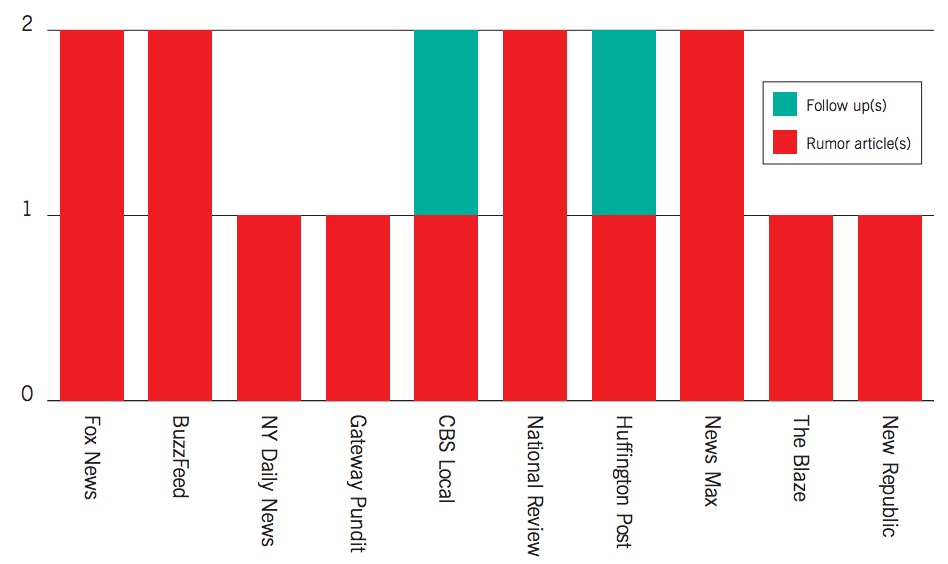

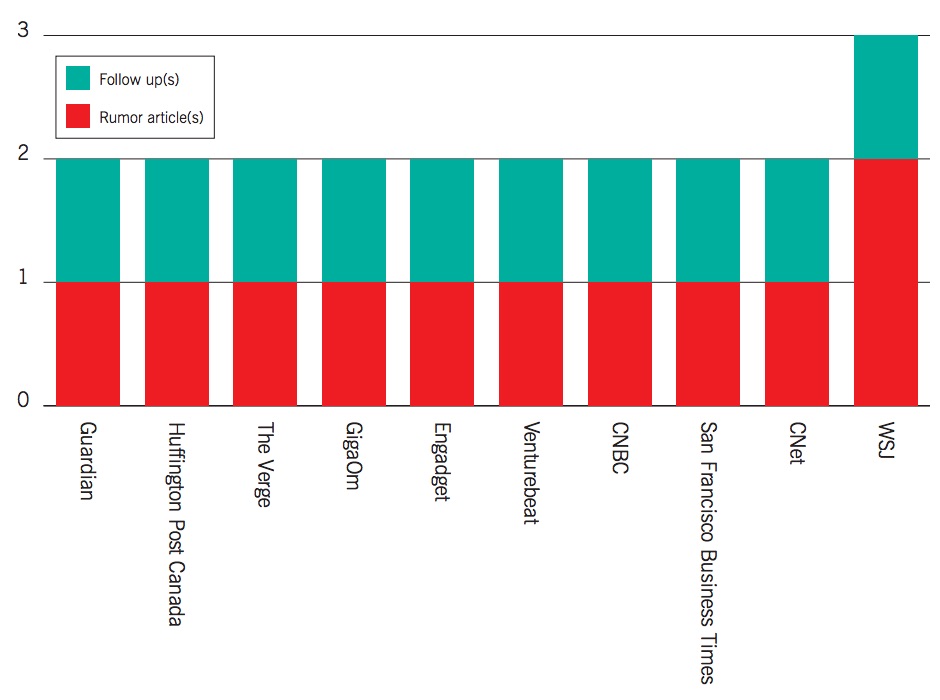

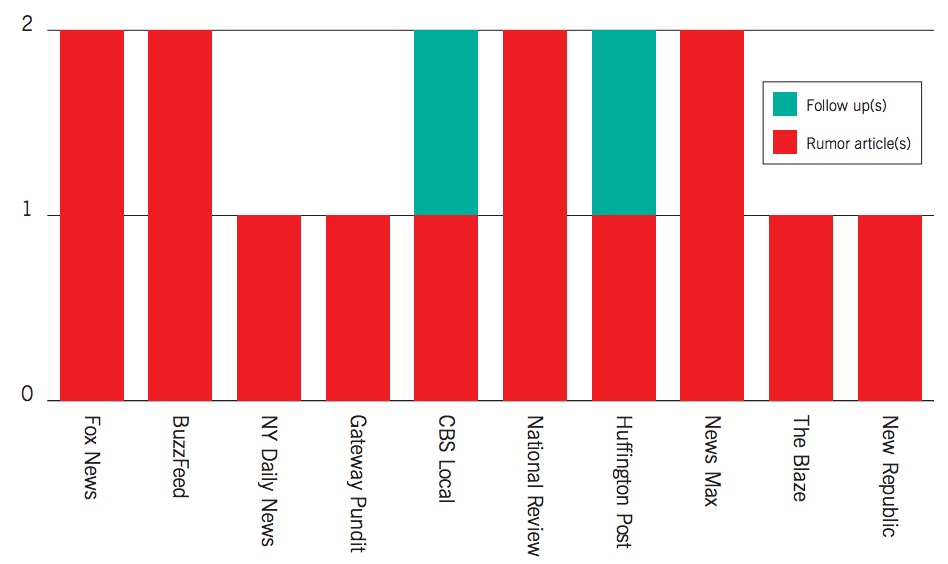

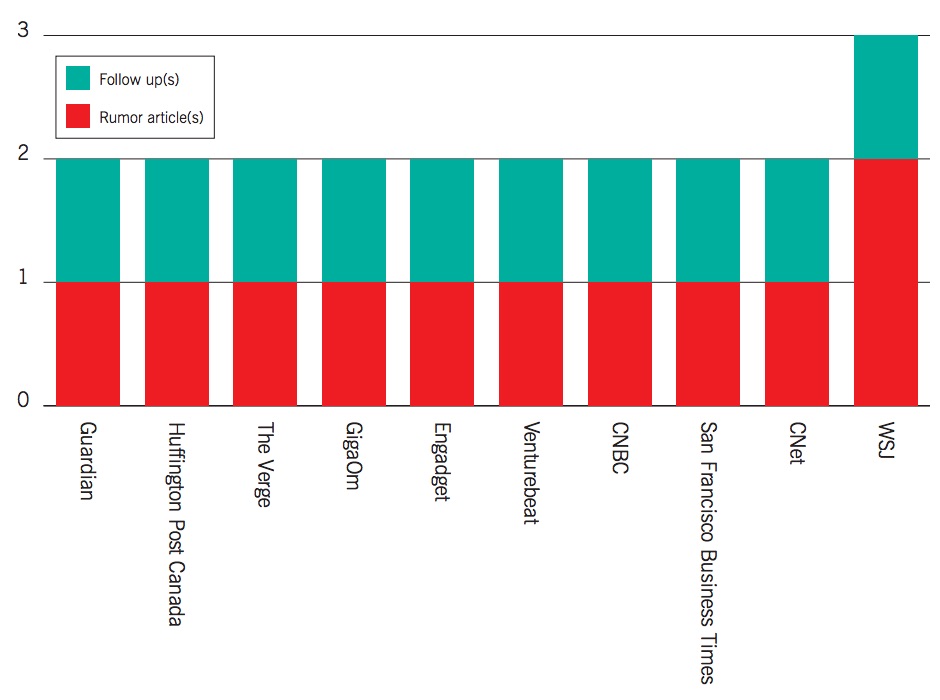

- News organizations are inconsistent at best at following up on the rumors and claims they offer initial coverage. This is likely connected to the fact that they pass them on without adding reporting or value. With such little effort put into the initial rewrite of a rumor, there is little thought or incentive to follow up. The potential for traffic is also greatest when a claim or rumor is new. So journalists jump fast, and frequently, to capture traffic. Then they move on.

- News organizations reporting rumors and unverified claims often do so in ways that bias the reader toward thinking the claim is true. The data collected using the Emergent database revealed that many news organizations pair an article about a rumor or unverified claim with a headline that declares it to be true. This is a fundamentally dishonest practice.

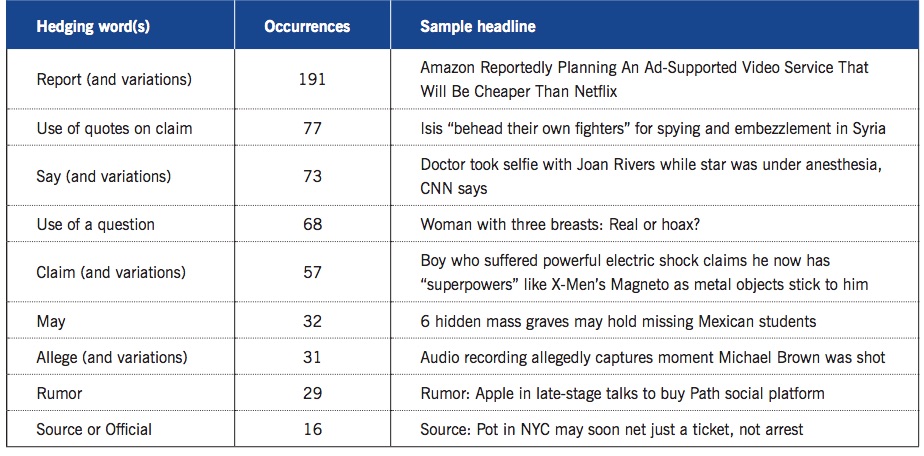

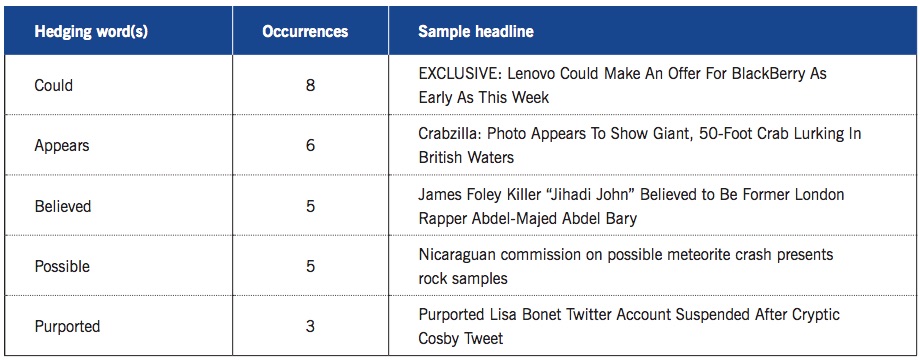

- News organizations utilize a range of hedging language and attribution formulations (“reportedly,” “claims,”etc.) to convey that information they are passing on is unverified. They frequently use headlines that express the unverified claim as a question (“Did a woman have a third breast added?”). However, research shows these subtleties result in misinformed audiences. These approaches lack consistency and journalists rarely use terms and disclosures that clearly convey which elements are unverified and why they are choosing to cover them.

Much of the above is the result of a combination of economic, cultural, temporal, technological, and competitive factors. But none of these justify the spread of dubious tales sourced solely from social media, the propagation of hoaxes, or spotlighting questionable claims to achieve widespread circulation. This is the opposite of the role journalists are supposed to play in the information ecosystem. Yet it’s the norm for how many newsrooms deal with viral and user-generated content, and with online rumors.

It’s a vicious-yet-familiar cycle: A claim makes its way to social media or elsewhere online. One or a few news sites choose to repeat it. Some employ headlines that declare the claim to be true to encourage sharing and clicks, while others use hedging language such as “reportedly.” Once given a stamp of credibility by the press, the claim is now primed for other news sites to follow-on and repeat it, pointing back to the earlier sites. Eventually its point of origin is obscured by a mass of interlinked news articles, few (if any) of which add reporting or context for the reader.

Within minutes or hours a claim can morph from a lone tweet or badly sourced report to a story repeated by dozens of news websites, generating tens of thousands of shares. Once a certain critical mass is met, repetition has a powerful effect on belief. The rumor becomes true for readers simply by virtue of its ubiquity.

Meanwhile, news organizations that maintain higher standards for the content they aggregate and publish remain silent and restrained. They don’t jump on viral content and emerging news—but, generally, nor do they make a concerted effort to debunk or correct falsehoods or questionable claims.

This leads to perhaps my most important conclusion and recommendation: News organizations should move to occupy the middle ground between mindless propagation and wordless restraint.

Unfortunately, at the moment, there are few journalists dedicated to checking, adding value to, and, when necessary, debunking viral content and emerging news. Those engaged in this work face the task of trying to counter the dubious content churned out by their colleagues and competitors alike. Debunking programs are scattershot and not currently rooted in effective practices that researchers or others have identified.

The result is that today online news media are more part of the problem of online misinformation than they are the solution. That’s depressing and shameful. But it also opens the door to new approaches, some of which are taking hold in small ways across newsrooms. A first, essential step toward progress is to stop the bad practices that lead to misinforming and misleading the public. I offer several practical recommendations to that effect, drawing upon research conducted for this report, as well as decades of experiments carried out in psychology, sociology, and other fields.

Another point of progress for journalists includes prioritizing verification and some kind of value-add to rumors and claims before engaging in propagation. This, in many cases, requires an investment of minutes rather than hours, and it helps push a story forward. The practice will lead to debunking false claims before they take hold in the collective consciousness. It will lead to fewer misinformed readers. It will surface new and important information faster. Most importantly, it will be journalism.

My hope is that news organizations will begin to see how they are polluting the information stream and that there is an imperative and opportunity to stop doing so. Organizations that already have good practices might also recognize that they can—and must—engage more with emerging news and rumors to help create real understanding and spread truth.

There is simply no excuse. We can and must do better.

Introduction: The New World of Emergent News

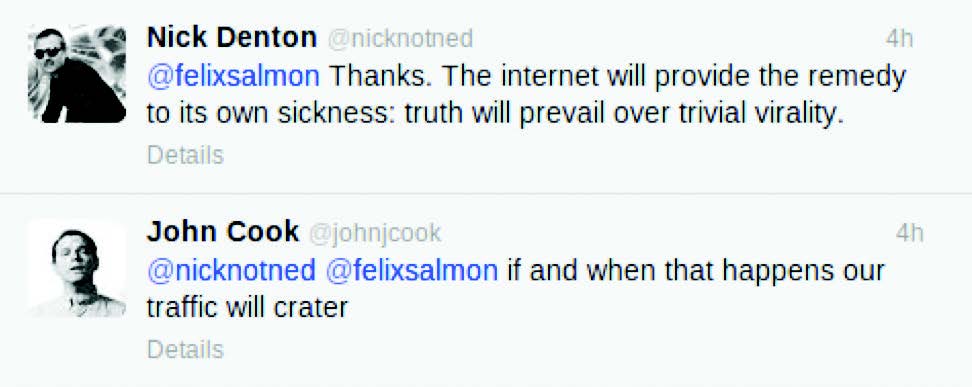

“It’s out there,” said Gawker Media founder Nick Denton. “Half of it’s right. Half of it’s wrong. You don’t know which half is which.” Denton was speaking to Playboy in an interview about today’s news and information environment.1

Reaching well over one hundred million unique visitors a month, Denton’s company is among the most popular and powerful of a new class of online media. The group’s eponymous flagship site regularly aggregates content that is already being shared or discussed online, or has the potential to go viral. This leads Gawker to feature those “out there” rumors and unverified claims and stories Denton described.

Often, that content ends up being false, or is not what it first appeared to be.

“Part of our job is to make sure we’re writing about things that people are talking about on the Internet, and the incentive structure of this company is organized to make sure that we are on top of things that are going viral,” said John Cook, the then-editor in chief of Gawker in a subsequent discussion about unverified viral content. “We are tasked both with extending the legacy of what Gawker has always been—ruthless honesty—and be reliably and speedily on top of Internet culture all while getting a shit-ton of traffic. Those goals are sometimes in tension.”2

Be they traditional publishers looking to gain a foothold online or the new cadre of online media companies, a wide range of news organizations feel this tension. What they share is an aspiration to plug into what’s trending and gaining attention online, and reflect (and monetize) that with their digital properties.

At the same time, digital natives and legacy media alike all seek to build or maintain a trusted brand and be seen as quality sources of information. Chasing clicks by jumping on stories that are too-good-to-check inevitably comes into conflict with the goal of audience loyalty.

Too often news organizations play a major role in propagating hoaxes, false claims, questionable rumors, and dubious viral content, thereby polluting the digital information stream. Indeed some so-called viral content doesn’t become truly viral until news websites choose to highlight it. In jumping on unverified information and publishing it alongside hedging language, such as “reportedly” or “claiming,” news organizations provide falsities significant exposure while also imbuing the content with credibility. This is at odds with journalism’s essence as “a discipline of verification”3 and its role as a trusted provider of information to society.

A source of the tension between chasing clicks and establishing credibility is the abundance of unverified, half-true, unsourced, or otherwise unclear information that constantly circulates in our real-time, digital age. It’s a result of the holy trinity of widespread Internet access, the explosion of social networks, and the massive market penetration of smartphones.

Today, rumors and unverified information make their way online and quickly find an audience. It happens faster and with a degree of abundance that’s unlike anything in the history of journalism or communication.

Rumors constantly emerge about conflict zones, athletes and celebrities, politicians, election campaigns, government programs, technology companies and their products, mergers and acquisitions, economic indicators, and all manner of topics. They are tweeted, shared, liked, and discussed on Reddit and elsewhere. This information is publicly available and often already being circulated by the time a journalist discovers it.

What we’re seeing is a significant change in the flow and lifecycle of unverified information—one that has necessitated a shift in the way journalists and news organizations handle content. Some of that shift is conscious, in that journalists have thought about how to report and deliver stories in this new ecosystem. Others, however, act as if they have not, becoming major propagators of false rumors and misinformation.

This paper examines the spread of unverified content and rumor in the online environment, and how newsrooms currently handle this type of information. It offers practical advice for better managing emerging stories and debunking the misinformation that is their inevitable byproduct. The intent of this report is to present best practices and data-driven advice for how journalists can operate in a digitally emergent environment—and do so in a way that helps improve the quality of confirmation, rather than degrade it.

The Opportunity and Challengeof Rumor

Journalists, by nature, love rumors and unverified information. Developing information tantalizes with the promise of not only being true, but also being as yet unknown on a large scale. It’s hidden knowledge; it’s a scoop.

At its best, rumor is the canary in the coal mine, the antecedent to something big. But it can also be the early indicator of a hoax, a misunderstanding, or a manifestation of the fears, hopes, and biases of a person or group of people.

Rumors and unverified information often lack context or key information, such as their original source. This presents enough of a pervasive issue for journalists today that a company like Storyful now exists (and was acquired by News Corp). A social media newswire, Storyful employs journalists to sift through the mass of content on social networks to verify what’s real and to keep their newsroom customers away from fake and unverified content.

One major challenge to emergent news is that humans are not well equipped to handle conflicting, ambiguous, or otherwise unverified information. Research detailed in this report shows that our brains prefer to receive information that conforms to what we already know and believe. The idea that a situation is evolving, still unformed, and perhaps rife with hearsay frustrates us. We want clarity, but we’ve been dumped into the gray.

The human and cognitive response to this is to do our best to make sense of what we’re seeing and even of what we don’t yet know. As a result, we retreat to existing knowledge and biases. We interpret and assimilate new information in a way that reinforces what we already believe, and we may invent possible outcomes based on what we hope or fear might happen. This is how rumors start. As inherently social beings, we seek to make sense of things together and to transmit and share what we know.

Today, as the saying goes, there’s an app for that.

Need for Debunking

The recent outbreak of Ebola in West Africa, for example, unleashed a torrent of online rumors—some true and many false. In early October, a woman in the United Kingdom contacted me to note that she had just received this message via the messaging app WhatsApp:

Ebola virus is now in the UK. PLEASE be very careful especially on public transports. Here are the list of hospitals that have ebola patients. Royal free hospital (north London). Newcastle upon Tyne hospital. Sheffield teaching hospital. royal Liverpool university hospital. Nurses are being infected too. Please BC to ur loved ones.

She said it came from a friend who is a nurse. At the time it was circulating, and at the time of this writing, there were no confirmed Ebola patients in the U.K. But fear of that possibility had birthed a rumor that was now spreading via at least one messaging app, and which could also be found on Facebook.

At roughly the same time that false message was circulating, people on Twitter were talking about a possible Ebola patient in Richmond, Virginia:

Virginia had recently tested two patients exhibiting Ebola-like symptoms. The tests were negative, and again, as of this writing, there are no confirmed Ebola cases in the state.

Later that same month, media outlets in New York began reporting claims that a doctor who had recently returned from West Africa was being treated as a possible Ebola case. On October 23, The New York Post published a story, “Doctor who treated Ebola patients rushed to NYC hospital”:

A 33-year-old Doctors Without Borders physician who recently treated Ebola patients in Guinea was rushed in an ambulance with police escorts from his Harlem home to Bellevue Hospital on Thursday, sources said.4

That claim proved to be true.

The challenge today for newsrooms is to find new and better ways to do our work amidst this unprecedented onslaught of ambiguity and rumor, and to do so in a transparent way that brings clarity to fluid situations—if not clear answers. Our responsibility to source and publish information also means we must debunk false rumors, hoaxes, and misinformation. This is more important today than ever before.

When the World Economic Forum asked members of its Network of Global Agenda Councils to name the top trends facing the world in 2014, they listed “the rapid spread of misinformation online” in the first ten. It was named along with issues such as “inaction on climate change,” “rising social tensions in the Middle East and North Africa,” and “widening income disparities.”5

“In this emergent field of study we need solutions that not only help us to better understand how false information spreads online, but also how to deal with it,” wrote Farida Vis, a research fellow at the University of Sheffield, who is a member of the WEF Councils and has conducted research into the spread of online misinformation. “This requires different types of expertise: a strong understanding of social media combined with an ability to deal with large volumes of data that foreground the importance of human interpretation of information in context.”6

Journalists play an important role in the propagation of rumors and misinformation. Vis cited research from the book Going Viral that underscores the importance of “gatekeepers” in helping spread information online. “These gatekeepers—people who are well placed within a network to share information with others—are often old-fashioned journalists or people ‘in the know,’ ” Vis said.7

Our privileged, influential role in networks means we have a responsibility to, for example, tell people in Virginia that there are no confirmed cases of Ebola and to ensure we strongly consider when and how we propagate rumors and unverified information.

Not long after the WEF published its list of top trends for 2014, BuzzFeed’s Charlie Warzel predicted another trend for the year. “If you’ve been watching Twitter or Facebook closely this month, you may have noticed the emergence and increasingly visible countercurrent: 2014, so far, is shaping up to be the year of the viral hoax debunk,” he wrote. “It’s a public, performative effort by newsrooms to warn, identify, chase down, and explain that … story you just saw—most likely on Facebook.”8

He continued:

Truth telling and debunking are fundamental journalistic acts, online or otherwise, but the viral debunk is a distinctive take on an old standby; it’s a form-fitting response to a new style of hoax, much in same the way that Snopes and Hoax-Slayer were an answer to ungoverned email hoaxes, or that Politifact and FactCheck.org arose in response to a narrow, but popular, category of misinformation—false statements by public figures, uncritically amplified in the frenzy of political campaign.9

Warzel suggested this emerging practice was in reaction to a new breed of viral hoaxes that attract a huge number of social shares and pollute people’s social feeds. Technology site The Verge also examined the problem of fake news and hoaxes in the fall of 2014 when Ebola hoaxes were rampant.

“On Facebook, where stories look pretty much the same no matter what publication they’re coming from, and where news feeds are already full of panicked school closures, infected ISIS bogeymen, and DIY hazmat suits, the stories can fool inattentive readers into thinking they’re real,” wrote Josh Dzieza in his article. “Fake news sites are using Facebook to spread Ebola panic.” In response, readers shared the story, “spreading the rumor farther and sending more readers to the story, generating ad revenue for the site.”10

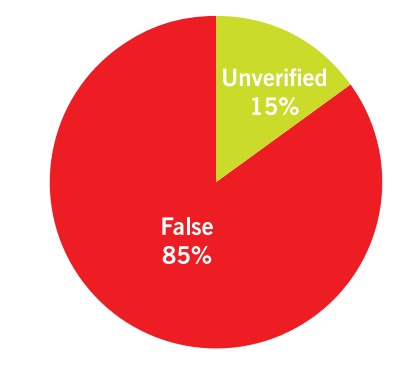

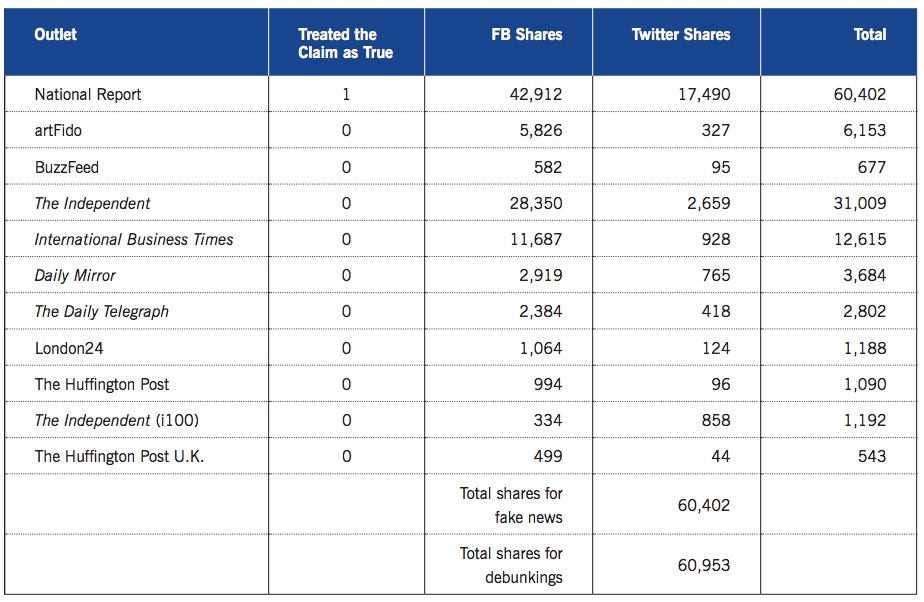

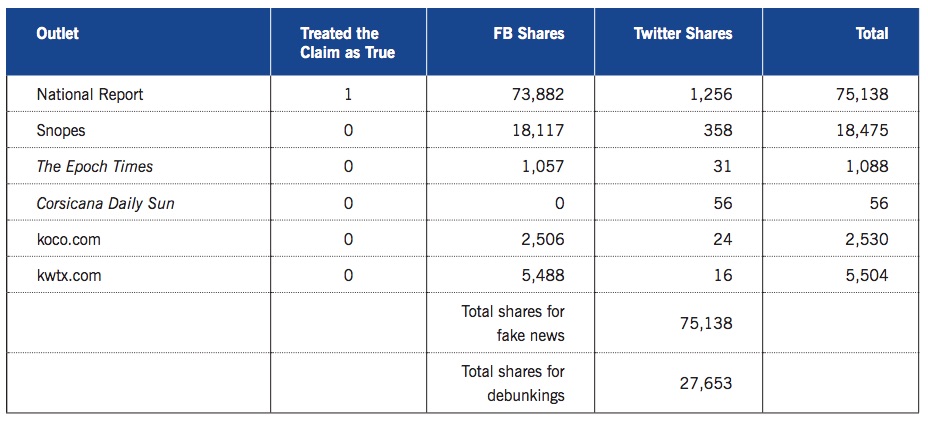

Dzieza pointed to an article from the fake news website NationalReport.net that falsely claimed an entire Texas town had been quarantined for Ebola. It quickly racked up over 130,000 likes and shares on Facebook. In research conducted for this paper, we identified five debunking articles from Snopes, The Epoch Times, and local Texas news outlets and discovered that, together, they achieved only a third of the share count of the panic-inducing fake.

Clearly, there is more work to be done in creating truly viral debunkings.

Filling the Gap

The importance and difficulty of addressing the spread of misinformation is arguably matched by a dearth of actionable data and advice for how to manage that task. This report presents quantitative and qualitative data to begin to fill that gap.

To gather data and information, I surveyed and interviewed journalists involved in covering real-time news and verifying emerging information—primarily information found on social networks.

I spoke with journalists, skeptics, and others who dedicate at least part of their time to debunking misinformation. This was all done in tandem with a review of the relevant scientific literature written by psychologists and sociologists over the last century about rumors, misinformation, and the challenges inherent in correcting misinformation.

I also worked with data journalist Adam Hooper and research assistant Joscelyn Jurich to create and populate a database of rumors reported in the online press. We used this database, dubbed Emergent, to power the public website Emergent.info, where people could see the rumors we were following and view the related data we were collecting.

The goal was to aggregate data that could offer a picture of how journalists and newsrooms report online rumors and unverified information. We also sought to identify false rumors that were successfully debunked, in the hope of identifying the characteristics of viral debunkings, if such a thing exists. As noted above, we measured the effectiveness of these debunkings using social shares as a metric.

The goal of this work, along with capturing how news organizations handle the onslaught of unverified information, is to offer suggestions for how journalists can better report unverified information and deliver more effective debunkings. You’ll find those covered most explicitly in the final chapter.

If “out there” is the new normal, then journalists and newsrooms need to be better equipped to meet the challenge of wrangling already-circulating stories. This work is a first step in that direction.

Literature Review: What We Know About the What, How, and Why of Rumors

Rumor Theory and the Press

It’s a very direct offer: Pay us money and we’ll give you rumors.

It works for ESPN. Rumors are a core part of the pitch for the outlet’s Insider subscription. It promises members exclusive access to Rumor Central, a website section where ESPN lists and analyzes the latest rumors about teams, players, and other aspects of sports.11

ESPN isn’t alone in monetizing and promoting rumor. The business and technology press thrive on hearsay—actively seeking out claims about earnings, new products, mergers and acquisitions, hirings and firings—to publish, sometimes with little sourcing. This is perhaps unsurprising given the old trader’s adage that advises people to “buy the rumor and sell the fact.” In the tech world, there’s even a small industry built around Apple product rumors. Websites such as MacRumors, Cult of Mac, AppleInsider, the Boy Genius Report, and others compete to source and report rumblings about the next iPhone, iPad, or Apple Watch.

These claims aren’t without effect. A 2014 study of merger rumors in the financial press found that “rumors in the press have large stock price effects.”12 Companies, like J.C. Penney, have seen their stock prices drop after rumors took hold on message boards, the trading floor, Twitter, and elsewhere.13 Researchers Kenneth R. Ahern and Denis Sosyura found that the “market overreacts to the average merger rumor, suggesting that investors cannot perfectly distinguish the accuracy of merger rumors in the press.”14

One reason why investors are bad at capturing full rumor value, according to the co-authors, is that they “do not fully account for the media’s incentive to publish sensational stories.”15 Sensational or not, rumors are a constant feature of journalistic work. Journalists seek out rumors, exchange them among themselves, and frequently report, propagate, and even directly monetize them.

To understand the larger context of the data in this paper about how online media handle rumors and unverified information, it’s important to explore the broader history and dynamics of rumor. Psychologists, sociologists, and others have conducted research into the nature and cause of it for close to a century. Their work offers much in the way of helping journalists evaluate and appreciate why rumors are invented and spread, and the powerful role the press plays in allowing people to believe them.

Why We Rumor

In their exhaustive look at rumor research and scholarship, Rumor Psychology: Social and Organizational Approaches, psychologists and researchers Nicholas DiFonzo and Prashant Bordia define rumor as:

. . . unverified and instrumentally relevant information statements in circulation that arise in contexts of ambiguity, danger, or potential threat and that function to help people make sense and manage risk.16

While theirs is a somewhat clinical definition, it communicates the key aspects of rumors: By their nature, they are unverified, emerge in specific contexts (danger, risk, etc.), and perform a distinct function.

Another characteristic of rumors is that they are communicated. They spread. “A rumor is not seated at rest inside an individual; it moves through a set of persons,” wrote DiFonzo and Bordia. “A rumor is never merely a private thought. Rumors are threads in a complex fabric of social exchange, informational commodities exchanged between traders.”17

They move by way of the technological means available and quickly adapt to new mediums. “Rumors readily propagate through whatever medium is available to them: word-of-mouth, email, and before email, even Xerox copies,” wrote a group of researchers from Facebook in a study of rumor cascades on the social site.18 “With each technological advancement that facilitates human communication, rumors quickly follow.”19

Rumor, simply put, is one of the ways humans attempt to make sense of the world around them. (Journalists are arguably trying to perform a similar service for people, but with facts and evidence.) They are not an accident, a mistake, or something we can fully stamp out. They are core to the human experience. “We are fundamentally social beings and we possess an irrepressible instinct to make sense of the world,” wrote DiFonzo in a blog post for Psychology Today. “Put these ideas together and we get shared sensemaking: We make sense of life together. Rumor is perhaps the quintessential shared sensemaking activity.”20

Natural disasters, such as Hurricane Sandy or Hurricane Katrina, birth an enormous number of rumors; so does a mysterious country like North Korea. Around these situations, we are trying to understand what’s happening but lack the information to do so. We engage in talk to help us better render what we cannot fully comprehend, what we don’t know. Rumors emerge to help us fill in gaps of knowledge and information. They’re also something of a coping mechanism, a release valve, in situations of danger and ambiguity.

Sociologist Tamotsu Shibutani outlined some of the situations that are ripe for rumor in his 1966 work Improvised News: A Sociological Study of Rumor. They include:

. . . situations characterized by social unrest. Those who undergo strain over a long period of time—victims of sustained bombings, survivors of a long epidemic, a conquered populace coping with an army of occupation, civilians grown weary of a long war, prisoners in a concentration camp, residents of neighborhoods marked by ethnic tension . . .21

Shibutani said the distinction between news and rumor is that the former is always confirmed, whereas the latter is unconfirmed. (The data presented farther into this paper challenges that distinction.)

Given Shibutani’s findings, it’s not surprising that interest in the study of rumor gained momentum during the Second World War. Wartime, with its elements of fear, uncertainty, and secrecy is fertile ground for rumor.

Types of Rumors

In his 1944 study of wartime communication, R.H. Knapp analyzed more than 1,000 rumors. He categorized them in three ways, according to DiFonzo and Bordia. There were “dread rumors” (or “bogies”), which expressed fear of a negative outcome; “wish rumors” (also called “pipe-dream” rumors), which were the opposite; and “wedge-driving” rumors, which are “expressive of hostility toward a people-group.”22 Authors DiFonzo and Bordia note that a fourth category was added a few years later: “curiosity rumors,” which are characterized by their “intellectually puzzling” nature.23

Which type of rumor have researchers found to be most prevalent? Sadly, it’s the dread-based kind. At a time when “explainer journalism” has become a trend, thanks to sites such as vox.com, rumors often emerge to provide explanation and context for events. “In ordinary rumor we find a marked tendency for the agency to attribute causes to event, motives to characters, a raison d’être to the episode in question,” (emphasis in original) wrote Gordon W. Allport and Leo Postman in The Psychology of Rumor.24 Along with sensemaking, “threat management” is a chief function of rumor. For people in dangerous or anxious situations, a rumor “rationalizes while it relieves.”25

But the rumor mill can also cause panic, riots, and civil disorder. DiFonzo and Bordia recounted the outcome of a rumor in 2003 during the outbreak of SARS:

False rumors that Hong Kong had been an area infected by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused widespread panic there . . . Telephone networks became jammed with people spreading the rumor, which resulted in bank and supermarket runs.26

Rumor Propagation

The stories we make up, the rumors we invent and spread, say something about our current situations. In this respect, rumors are valuable because, even when false, they reveal larger truths. They show what we think, fear, and hope. They are windows into our state of mind and beliefs. “[F]ar from being merely idle or malicious gossip, rumor is deeply entwined with our history as a species,” wrote Jesse Singal in a 2008 Boston Globe article examining how the Obama and McCain campaigns were working to quash rumors during the election process. “It serves some basic social purposes and provides a valuable window on not just what people talk to each other about, but why. Rumors, it turns out,” Singal continued, “are driven by real curiosity and the desire to know more information. Even negative rumors aren’t just scurrilous or prurient—they often serve as glue for people’s social networks.”27

The above reference to social networks relates to the person-to-person type, rather than Facebook and Twitter. But it reinforces that new digital networks amplify and accelerate a process that has existed as long as we humans have.

This is one area where it’s important to distinguish between rumor and gossip. If rumor is about sensemaking, then gossip is about social evaluation and maintenance. According to DiFonzo and Bordia, “Rumor is intended as a hypothesis to help make sense of an unclear situation whereas gossip entertains, bonds and normatively influences group members.”28 That’s why rumors, rather than gossip, are more closely linked with the press—given their connection to larger events. Hence why journalists often find themselves in roles of rumor propagators.

In his book On Rumors, Cass Sunstein summarized the four types of rumor propagators:

- Narrowly self-interested: “They seek to promote their own interests by harming a particular person or group.”

- Generally self-interested: “They may seek to attract readers or eyeballs by spreading rumors.”

- Altruistic: “When starting or spreading a rumor about a particular individual or institution, propagators often hope to help the cause they favor.”

- Malicious: “They seek to disclose and disseminate embarrassing or damaging details, not for self-interest or to promote a cause, but simply to inflict pain.”29

Most would characterize the online press as generally self-interested rumor propagators. They spread rumors because they expect to gain traffic or attention. The viral stories analyzed later in this report, including the Florida woman who claimed to have had a third breast implanted, offer little, if any, public or information value beyond being funny or shocking. Press outlets cover and propagate these stories because they attract eyeballs and promote social shares. They typically fit into the category of curiosity rumors.

Of course, journalists can also have altruistic goals. They want to bring important, relevant, or otherwise noteworthy information to the attention of the public. Finally, there’s also an argument to be made that journalists engage in narrowly self-interested and malicious propagation, though these more extreme cases are less common.

The above categories of propagators are useful to help journalists analyze their motivations for publishing unconfirmed stories. They also provide journalists with a framework to assist in evaluating the veracity of rumors and to examine why a rumor spreads among a specific group of people. The bottom line is that journalists should always evaluate the motivations of those engaged in rumor-mongering—including themselves.

Rumor Relevance and Veracity

Along with the motivations of a propagator, it’s also important to consider his or her connection to the given topic of a rumor. The more we care about a topic, or have a stake in it, the more likely we are to engage in its creation and spread. (Another element revealed in rumor research is the idea of imminent threat; if we feel that a rumor helps raise awareness about a threat, we are more likely to pass it along.)

Simply put, we’re more likely to spread a rumor if it has personal relevance. In a 1991 article for American Psychologist, rumor researcher Ralph Rosnow wrote that “rumor generation and transmission result from an optimal combination of personal anxiety, general uncertainty, credulity, and outcome-relevant involvement.”30 DiFonzo and Bordia similarly noted, “People are uncertain about many issues, but they pursue uncertainty reduction only on those topics that have personal relevance or threaten the goal of acting effectively.”31

Another element of rumor propagation relates to veracity. People are more likely to transmit a rumor if they believe it to be true. This is because we innately understand the negative reputational effects that come with being a source of false information. “Possessing and sharing valued information is also a way to heighten status and prestige in the view of others in one’s social network,” said DiFonzo and Bordia.32 Research has found that “a reputation as a credible and trustworthy source of information is vital for acceptance in social networks.”33

Both of the above quotes easily apply to journalists. Possessing valued information (scoops or new facts) heightens our status. Being seen as reputable and credible also raises our standing. The former explains why we might be inclined to push forward with rumors, while the latter provides reason for us to be more cautious.

In the end, however, it’s often the case that heedfulness gives way to the press’ desire to be seen as valuable, singular authorities. Perhaps no recent news story highlighted the tendency to seek shared sensemaking and threat management better than the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight Mh570.

Rumor and the 24-Hour News Cycle

When Mh570 went missing in March of 2014, it created a perfect storm of rumor-mongering in the press. A plane carrying 239 people vanished somewhere (presumably) in the Indian Ocean. This was an event that captured global attention. It was characterized by fear and a remarkable lack of real information: about where the plane was, why it crashed, who was responsible, and how a large jet could simply disappear in an age of radar and other advanced technology.

This set off a never-ending news cycle in which journalists sought out any piece of information or expert opinion, no matter how dubious, to aid in the process of making sense of the situation.

The drive to fill the empty space with something—particularly on cable news—was partly human nature, and also partly dependent on the need to meet the public’s insatiable demand for information. All of us—journalists and the public—sought to understand what had happened. But facts were sparse. So we engaged in collective sensemaking and rumor propagation to fill the void.

“On CNN, the plane rises from misty clouds accompanied by an eerie background score while anchors offer intriguing details—some new, some days old—of the disappearance of Flight 370,” wrote Bill Carter, The New York Times’ television reporter, in an article about cable news coverage of the story. “The reports, broadcast continually, often are augmented by speculation—sometimes fevered, sometimes tempered—about where the flight might have come to rest. And viewers are eating it up.”34

CNN more than doubled its audience in the two weeks after the plane first disappeared.35 People wanted information, and CNN dedicated seemingly every minute to the plane story. It also struggled to fill the void with real information. At times, segments were based largely on getting people to offer theories about what had happened. It was an invitation for rumor and speculation. This is a sample exchange from a CNN broadcast on March 11, just days after the plane disappeared (emphasis added):

RICHARD QUEST, CNN: . . . So, many questions, none of which, frankly, we’re going to be able to answer for you tonight. But many questions are raised by this new development. For instance, not least, how can a plane go like this and no one notices it’s off flight plan?

The former director general of IATA says he finds it incredible that fighter jets were not scrambled as soon as the aircraft went off course. I asked Giovanni Bisignani for his gut feeling about what happened to the plane.

Giovanni Bisigani, former Director General, IATA: It is difficult to imagine a problem in a structure failure of the plane. The Boeing 777 is a modern plane, so it’s not the case. It’s not a problem of a technical problem to an engine because in that case, the pilot has perfectly (sic) time to address this and to inform the air traffic control.36

CNN was often accused of being the worst offender when it came to over-coverage and rampant speculation. Longtime CNN host Larry King told Capital New York that he had “learned nothing,” from the channel’s reporting about the story and that “all that coverage has led to nothing.” He then called the coverage “absurd.”37

CNN was not alone in its rumor propagation, however. Many other outlets also engaged. There were soon an abundance of theories and rumors circulating, ranging from the plane’s landing in Nanning, China38 or North Korea,39 to its having been taken over by Iranian terrorists.40 In Carter’s Times article, Judy Muller, a former ABC correspondent and now a professor of journalism at the University of Southern California, characterized the combination of information-seeking, sense-making, and news-cycle pressures that came together in the story:

I fear I am part of the problem. I keep tuning in to see if there are any new clues . . . Of course, endless speculation from talking heads soon defines the coverage and that can lead to the impression that these folks know something when what they really know is that they have a 20-minute segment to fill.41

Infinite time to fill (or space online) plus a lack of real information about a global news event rife with uncertainty caused journalists to inundate the void with a constant stream of sensemaking and threat management in the form of “expert” commentary and imagined scenarios. Tom McGeveran, a co-founder of Capital New York, expressed his frustration with the onslaught of rumor and speculation in a tweet:

But given the inmate human processes at play in the creation and spread of rumors, that’s often truly easier said than done for the press.

Rumor and Belief

What makes us believe a rumor? And how do we evaluate its accuracy, if at all?

This is an important aspect of rumor. Evidence supports a connection between repetition and belief. “Once rumors are current, they have a way of carrying the public with them,” wrote R.H. Knapp in his 1944 study of wartime rumors. “Somehow, the more a rumor is told, the greater its plausibility.”42 This presents a significant challenge to journalists’ ability to debunk false rumors, as I’ll detail in the third section of this chapter.

Another factor that aids in the believability of rumor specifically relates to the press. One study found “rumors gained plausibility by the addition of an authoritative citation and a media source from which the rumor was supposedly heard.”43

The source of a rumor is important, as is the frequency with which it is repeated, and any additional citations that seem to add to its veracity. The ability to cite a media source provides ammunition for rumor propagation. This concept illustrates how important it is for journalists and news organizations to think about which rumors they choose to repeat and how they do so.

In summarizing what leads to belief in rumors, DiFonzo and Bordia listed four factors, as well as a set of “cues” that people use to evaluate rumor accuracy:

. . . rumors are believed to the extent that they (a) agree with recipients’ attitudes (especially rumor-specific attitudes), (b) come from a credible source, (c) are heard or read several times, and (d) are not accompanied by a rebuttal. Cues follow naturally from these propositions: How well does the rumor accord with the hearer’s attitude? How credible is the source perceived to be? How often has the hearer heard the rumor? Has the hearer not been exposed to the rumor’s rebuttal?44

These evaluations take place in the moments when we hear and process a rumor. It’s a rapid-fire assessment that mixes cognitive and emotional factors—and any evidence of media participation in the rumor can be a factor in what we ultimately choose to believe.

With the emergence of digital social networks, our instant evaluation of a rumor can now be followed by a remarkably powerful act of push-button propagation. Once we decide that a rumor is worth propagating, we can do so immediately and to great effect. This is particularly true when it comes to journalists and news organizations, as they have access to a larger audience than most. By giving a rumor additional attention in its early, unverified stage, they add credibility and assist in its propagation, which itself has an effect on belief.

“Rumors often spread through a process in which they are accepted by people with low thresholds first, and, as the number of believers swells, eventually by others with higher thresholds who conclude, not unreasonably, that so many people cannot be wrong,” wrote Sunstein.45 The result can be the rapid spread—and increased belief in—online misinformation.

The Power of Misinformation

She was dressed in fatigues with a rifle at her side. The camera focused as she smiled and flashed the “v” sign while surrounded by other fighters. She would soon be known as Rehana, the “Angel of Kobane.”

Her name and image came to global attention beginning on October 13, 2014, when an Indian journalist/activist named Parwan Durani tweeted that the woman in the photo, whom he called Rehana, had killed more than 100 Islamic State fighters.46 Durani called for people to retweet his message to celebrate her bravery. Nearly 6,000 did, and soon news articles began reporting the remarkable story of Rehana, the ISIS slayer.

Not long after, ISIS supporters claimed that she had been killed. Social media accounts sympathetic to ISIS began circulating an image of a fighter holding a decapitated female head. They claimed it was Rehana.

Once again, the press picked up the story, this time to mourn her apparent death. “Poster girl for Kurdish freedom fighters in Kobane ‘captured and beheaded by ISIS killers’ who posted gruesome pictures online,” read a Daily Mail digital headline.47 Business Insider reported something similar: “On October 27, rumors began to spread on social media that a Kurdish female fighter known by the pseudonym Rehana may have been beheaded by Islamic State (ISIS) militants in Kobani.”48 Others, such as the Daily Mirror, news.com.au, Metro UK, and Breitbart, reported the rumor of her death, citing the tweets as potential evidence. The story moved quickly, with some questioning whether the ISIS image was real and whether the head really belonged to Rehana. Many dismissed it as propaganda.

The Daily Mirror’s story, for example, included a denial:

She is said to have killed more than 100 jihadists in the battle for the strategically important town of Kobane, on the Turkey-Syria border.

Now IS has claimed that a photo of a grinning rebel holding a woman’s severed head is evidence that she is dead.

But Kurdish journalist Pawan Durani said it was untrue.

He wrote today: “Rehana is very much alive. ISIS supporters just trying to lift morale.”49

Durani, of course, is not a Kurdish journalist and there is no evidence he had direct content with, or information about, Rehana. But that is the least of the concerns about the overall story. The question of whether she had ever been fighting ISIS and, in fact, if her name was actually Rehana soon eclipsed the issue of her alleged murder. The story had captured massive attention but seemed entirely based on falsities.

Swedish journalist Carl Drott is perhaps the only Western journalist to have met the woman in question. He felt compelled to set the record straight after her initial story began to take hold. Writing on Facebook, Drott noted it was “very unlikely” that she had killed 100 ISIS fighters, since she is a member of an auxiliary unit that does not go to the front. “I met her during the ceremony when the unit was set up on 22 August,” he wrote. “The purpose of such units is primarily to relieve YPG/YPJ (“the army”) and Asayish (“the police”) of duties inside Kobani town, e.g. operating checkpoints.”50

The BBC tracked the evolution of the Rehana story and confirmed Drott’s account that the image circulating was originally taken in August.51 “The following day [in August], this image was posted on the blog ‘Bijikurdistan’ which supports the Kurdish effort in Kobane,” reported the BBC. “It then seems to have gone largely unnoticed until it was shared on Twitter over a month later by an English-language news outlet based in the Kurdish region, Slemani Times.52 That is when the stories and mystery around her began building up on social media.”53

Then in October came the tweet from Durani—and a legend was born.

In his post, Drott said Rehana is not a common Kurdish name and he had no idea how it came to be given to the woman in the photo. He said he never caught her name when they briefly spoke in August. Drott reflected on how the photo took on a life of its own:

She volunteered to defend Kobani against the Islamic State and risk her life. It’s an affront to her that some people think that’s not enough, but that more fantastic details have to be invented, and it also devalues the very many completely true and even more fantastic stories coming out of Kobani. Unfortunately, there’s not an iconic picture for every fantastic story, and vice versa.54

With only a handful of stories that examined the contradictions and false claims around the Rehana story, for the most part it’s one example of how narratives are invented, picked up, and spread in today’s information ecosystem. The simple story of the attractive Kurd who killed dozens of ISIS fighters is a powerful wish rumor. Add in a compelling image and it’s perfect for propagation on social networks. The result is that most of us will never know the woman’s true story—and the press bears a level of responsibility for that.

In today’s networked world, misinformation is created and spreads farther and faster than ever before. Research finds that attempts to correct mistaken facts, viral hoaxes, and other forms of online misinformation often fall short. Thus, our media environment is characterized by persistent misinformation.

New York Times technology columnist Farhad Manjoo is the author of True Enough: Learning to Live in a Post-Fact Society, a detailed look at related scholarly research and examples of misinformation in our increasingly connected world. “People who skillfully manipulate today’s fragmented media landscape can dissemble, distort, exaggerate, fake—essentially, they can lie—to more people, more effectively, than ever before,” Manjoo wrote.55

The ranks of these people are growing, and so too is their impact, thanks to a combination of social networks, credulous online media, and the way humans process (mis)information.

Networks Don’t Filter for Truth

“False information spreads just like accurate information,” wrote Farida Vis, a Sheffield University research fellow, in an article examining the challenges of stopping online misinformation.56 Networks don’t discriminate based on the veracity of content. People are supposed to play that role.

“Online communication technologies are often neutral with respect to the veracity of the information,” said the group of researchers from Facebook in their paper looking at rumor cascades on the network. “They can facilitate the spread of both true and false information. Nonetheless, the actions of the individuals in the network (e.g., propagating a rumor, referring to outside sources, criticizing or retracting claims) can determine how rumors with different truth values, verifiability, and topic spread.”57

Another factor that determines the spread of misinformation is the nature of the information itself. Falsehoods are often more attractive, more shareable, than truth. “It’s no surprise that interesting and unusual claims are often the most widely circulated articles on social media. “Who wants to share boring stuff?” wrote Brendan Nyhan, a professor of political science at Dartmouth who has also conducted some of the best research into political misinformation and the attempts to correct it.58

Writing for The New York Times, Nyhan said, “The spread of rumors, misinformation and unverified claims can overwhelm any effort to set the record straight, as we’ve seen during controversies over events like the Boston Marathon bombings59 and the conspiracy theory60 that the Obama administration manipulated unemployment statistics.”61 (Nyhan was writing about the research project that led to this paper.)

One challenge Nyhan noted is that a fake story, or an embellished version of a real one, is often far more interesting and more shareable than the real thing. Whether it’s the Angel of Kobane, a fake news story about a Texas town under Ebola quarantine, or a Florida woman’s claim that she’s had a third breast implanted (more on that later in this paper), these narratives are built to appeal to our curiosity, fears, and hopes. They target the emotions and beliefs that cause us to treat things with credulity—and to pass them on.

Emma Woollacott, a technology journalist writing for Forbes, put it well:

Who doesn’t feel tempted to click on a picture of an Ebola zombie or a story of a miracle cure? And even if you don’t actually like or share the story, your interest is still noted by a plethora of algorithms, and goes to help increase its visibility. The irony is that false stories spread more easily than Ebola itself—despite what you may have read elsewhere.62

Stanford professor, urban-legend researcher, and bestselling business book author Chip Heath argued in “Emotional Selection in Memes: The Case of Urban Legends” that “rumors are selected and retained in the social environment in part based on their ability to tap emotions that are common across individuals.”63

Sites like Upworthy depend on this in order to make the content they curate spread. (Upworthy employs researchers to fact-check content before it’s promoted.) They work to inspire an emotional reaction. For example, Heath found that rumors evoking feelings of disgust are more likely to spread.

Just as networks don’t filter for true and false, the same can be said for our brains. When information conforms to existing beliefs, feeds our fears, or otherwise fits with what we think we already know, our level of skepticism recedes. In fact, the default approach to new rumors is to give them a level of credence. “Even when the hearer is generally skeptical, most situations don’t seem to call for skepticism,” wrote DiFonzo in Psychology Today. “Most of the time, trusting what other people tell us works for us, lubricates social relationships, bolsters our existing opinions, and doesn’t result in an obvious disaster—even if it is just plain wrong.” He continued, “Indeed, civilization generally relies on our tendency to trust others—and we tend to punish those who are caught violating that trust.”64

Misinformation often emerges and spreads due to the actions and mistakes of well-meaning people (including journalists). But there are also those engaged in the conscious creation and spread of falsehoods.

Misinformation Ecosystem

There is a growing online misinformation ecosystem that churns out false information at an increasing pace. Its success often depends on two factors: the ability to cause sharing cascades on social networks and the ability to get online media to assist in the propagation, thereby adding a layer of credibility that further increases traffic and sharing.

This ecosystem has, at its core, three actors.

1. Official Sources of Propaganda

The story of Rehana is, in part, a story of propaganda. As of this writing, it’s unknown exactly where the claim of her killing 100 ISIS fighters originated (though we know when it took hold on Twitter). That apparently false claim is a powerful piece of propaganda against ISIS and in favor of the Kurds. In turn, the Islamic State met this piece of anti-ISIS propaganda with its own response—a false claim that its fighters had beheaded Rehana.

Warring sides have always used propaganda to spread fear and doubt. Today, they do so online. After Malaysia Airline’s flight Mh37 was shot down over Ukraine in July, the Russian government made many attempts to place the blame on Ukrainian forces for downing the jet. Meanwhile, investigators such as Eliot Higgins, who goes by the pseudonym Brown Moses, gathered evidence from online sources to show that the Buk missile launcher that took down the jet came from Russia. In response, Russia engaged in an effort to refute the claim by creating its own “evidence” and seeding it online.

“Faced with evidence that its proxies in Ukraine had committed a terrible crime, Russian officials tried to turn the tables with a social media case of their own,” wrote journalist Adam Rawnsley in a post for Medium.65 (Rawnsley has worked for The Daily Beast and also written for Wired and Foreign Policy.)

Russian officials said that a YouTube video showing the Buk in fact revealed that it was in Ukrainian territory. “Russia pushed back on the claims, arguing that a blow-up image of the billboard showed an address in Krasnoarmeysk, a town in Ukrainian government control—the implication being that Buk was Ukrainian, not Russian,” Rawnsley wrote.66

Though the Kremlin claims were false, the government still managed to activate a network of sympathetic supporters and media outlets to propagate its refutation. Often, networks of fake accounts set up on Twitter help push out one side’s view.

Rawnsley quoted Matt Kodama, vice president of products at Recorded Future, which enables people to analyze large data sets (and has been funded by the CIA’s venture arm):

[In] A lot of these hoax networks, all the accounts will pop up all at the same time and they’ll all be following each other. But if you really map out how the accounts relate to each other, it’s pretty clear that it’s all phony.67

2.Fake News Websites

Satirical news sites such as The Onion and The New Yorker’s Borowitz Report are built on producing fake takes on real events and trends. However, these sites often have prominent disclaimers about the satirical nature of their content. (Of course, people still end up being fooled, as the website Literally Unbelievable shows.)68

But a new breed is emerging: websites that often don’t disclose the fake nature of their content and aren’t engaged in satirical commentary at all. Instead, they church out fake articles designed and written to present as real news. They do it to generate traffic and shares and to collect ad revenue as a result. These sites have official sounding names, such as The Daily Currant, National Report, Civic Tribune, World News Daily Report, and WIT Science. “These sites claim to be satirical but lack even incompetent attempts at anything resembling humor,” wrote Josh Dzieza in an article about Ebola hoaxes for The Verge. “They’re really fake news sites, posting scary stories and capitalizing on the decontextualization of Facebook’s news feed to trick people into sharing them widely.”69

Perhaps the worst offender is NationalReport.net. It offers no disclosure about its fake nature anywhere on the site and it regularly publishes articles that make alarming false claims.

When Ebola arrived in the United States, National Report soon began issuing daily stories about infections. At one point, it claimed that the town of Purdon, Texas had been quarantined after a family of five was infected with Ebola.70

The story read like a real news report, replete with comment from a source at a local hospital:

A staff member at the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, who wished to remain anonymous, contacted National Report with a short statement about the Ebola situation in Texas. We were told the following.

“As far as we know, Jack Phillis had not come in contact with either the late Thomas Duncan or Mrs. Phan. It is perhaps possible that he was within a close proximity of the infected parties, but it is otherwise unknown as to how Phillips was infected with Ebola.”71

The article invited readers to follow live tweets from the scene from Jane M. Agni, its reporter. Her bio, which is of course fake, says she is the author of The States Of Shame: Living As A Liberated Womyn In America and that the book “appeared on Oprah’s Book Club.”72 Agni is also listed as a writer for two other related fake websites, Modern Woman Digest73 and Civic Tribune.74

National Report published other Ebola stories, including, “Ebola Infected Passenger Explodes Mid-Flight Potentially Infecting Dozens.” To add credibility to that story, the site included a fake comment on the article from the supposed pilot of the flight:

I was the pilot for this flight and there is (sic) a few discrepancies in the story. Yes, the woman did pass away, and it is true that she tested positive for the ebola virus. However, she did not “explode” as your article implies. When her organs liquified, they fell out onto the floor of the plane, which resulted in a splashing sound. None of the other passengers (to my knowledge) were hit with any of her bodily fluids. Only the people in the read (sic) cabin are being held for testing, as that is where the woman in question was seated.75

The owner of the site goes by the pseudonym Allen Montgomery. He believes he’s acting in the public interest. “We like to think we are doing a public service by introducing readers to misinformation,” he told Digiday. “As hard as it is to believe, National Report is often the first place people actually realize how easily they themselves are manipulated, and we hope that makes them better consumers of content.”76

In an email to me, Montgomery said he created the site to understand online misinformation and virality. “I became aware of the feeding frenzy of misinformation on the fringe of the right wing years ago (along with the rise of the Tea Party) and wanted to learn more about how they were able to build such large and loyal followers who disseminated their information across the net while seeming to suspend reason,” he said. “As a news junkie myself, I figured I would throw my hat in the game and see how easily it was to infiltrate the fringe and sadly, it wasn’t difficult.”

Montgomery complained that he gets “the most vile death threats on a daily basis,” but said the hostility is misdirected. “I often tell them, to put it in rapper terms, ‘Don’t hate the player, hate the game,’ ” he wrote. “I myself am a player in a game that I hate.”

The reality is that Montgomery and others push out fake news every day, and they generate tens of thousands of shares, driving traffic that can reach more than one million uniques per month, according to Quantcast data on National Report.77 Ricardo Bilton, the author of the Digiday article, believes that the site is part of a bigger problem and ecosystem. “In reality, the site has placed itself at the center of a media environment that actively facilitates the spread of misinformation,” he wrote. “It’s really just a symptom of larger problems.”78

3. Individual Hoaxsters

Montgomery’s claim that he’s trying to expose the problems with online media and social networks is the same motivation purported by a solo hoaxster who prefers to work primarily on Twitter. On that network, Tommasso Debenedetti has impersonated the Russian defense minister, the Italian prime minister, Vatical official Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un, and former Afghan leader Hamid Karzai, among others. He cycles through fake accounts, bringing his followers with him when he can, tweeting out fake news reports. His goal is to get journalists to spread the news.

“Social media is the most unverifiable information source in the world but the news media believes it because of its need for speed,” he told The Guardian in 2012.79 Debenedetti says his day job is as a school teacher in Italy. But his passion is for fakery—and fooling the media.

Before he moved to Twitter, he wrote fake interviews with famous people and sold them to credulous Italian newspapers. The New Yorker outed him for this in 2010, but not before he’d sold and published fake interviews with Philip Roth, Mikhail Gorbachev, and the Dalai Lama.80

“I wanted to see how weak the media was in Italy,” he told The Guardian. “The Italian press never checks anything, especially if it is close to their political line, which is why the rightwing paper Libero liked Roth’s attacks on Obama.”81

Debenedetti is among the most dedicated and prolific of online hoaxsters, but many others crop up. There was the British teenager who convinced thousands of Twitter followers, and some professional athletes, that he was a prominent football writer for The Daily Telegraph and other publications.82

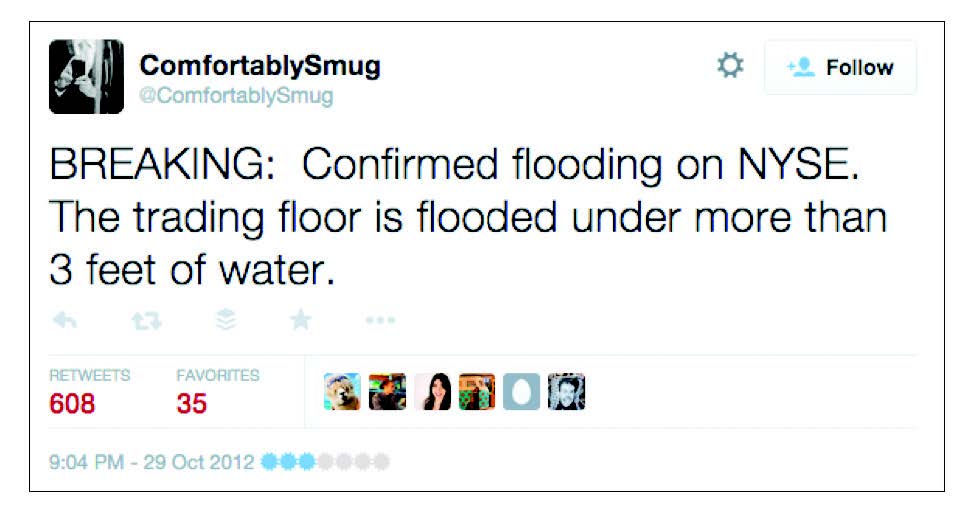

And there are people who use major events, such as Hurricane Sandy, as opportunities to push out false information, like this person (who, it turned out, worked in New York politics):

Journalists and news organizations soon began distributing this claim, many of them failing to offer any attribution:

If it’s newsworthy, such as the report of flooding at the NYSE, at least a few journalists are likely to jump on it prior to practicing verification. If one (or more) credible outlet moves the information, others are quick to pile on, setting off a classic information cascade. When a rumor or claim starts generating traffic and gets picked up by other media outlets, then it’s even more likely journalists will decide to write something.

The danger, aside from journalists becoming cogs in the misinformation wheel, is that it’s incredibly difficult to make corrections go just as viral.

Failure of Corrections

Two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013. In the ensuing hours, as people tried to understand what had happened, many items of misinformation were birthed and spread. Famously, there were attempts on Reddit to examine photos and other evidence to pinpoint those responsible. (That effort is the subject of a case study in a forthcoming Tow paper by Andy Carvin.)

Media outlets made mistakes. In some cases, they incorrectly reported that a suspect was in custody. The New York Post famously published a cover showing two young men who had been at the marathon and labeled the pair, “BAG MEN,” reporting that the FBI was looking for them. (The newspaper later settled with them for an undisclosed amount.)

A group of researchers investigated one false rumor claiming that one of the victims was an eight-year-old girl who had been running the race. (An eight-year-old boy had been at the marathon as a spectator, and he was killed in the blasts.) The rumor about the young girl began not long after news of the boy’s death became public. At least one Twitter user, TylerJWalter, appeared to conflate the two, tweeting, “An eight year old girl who was doing an amazing thing running a marathon, (sic) was killed. I can’t stand our world anymore.”

Then another Twitter user, _Nathansnicely, tweeted the same information, along with a picture of a young girl: “The 8 year old girl that sadly died in the Boston bombings while running the marathon. Rest in peace beautiful x https://t.co/mMOi6clz21.” (These tweets are no longer online.)

From there, the rumor began to spread.

Researchers from the University of Washington and Northwest University studied the dissemination of three false rumors associated with the Boston bombings. Their paper, “Rumors, False Flags, and Digital Vigilantes: Misinformation on Twitter after the 2013 Boston Marathon Bombing,” offers a look at how difficult it is to get corrections to spread as fervently (and via the same people) as the initial rumor.83

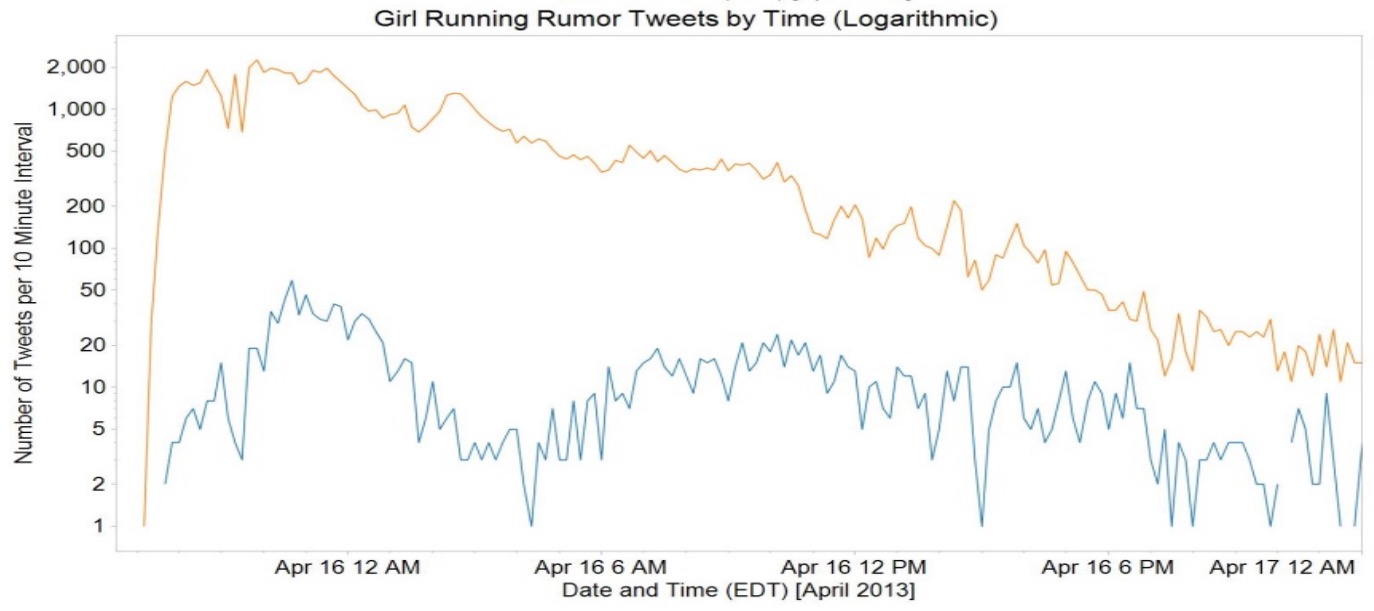

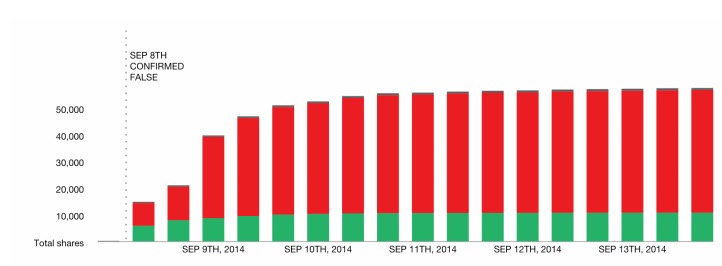

With regard to the rumor of the eight-year-old girl, they captured 90,668 tweets that referenced it as true. There were only 2,046 tweets that offered corrective information, “resulting in a misinformation to correction ratio of over 44:1.”84 The graph below from their paper illustrates the spread of misinformation versus corrections on Twitter. (Misinformation is in orange; the correction is in blue.)85

“Perhaps the most troublesome aspect of the graph shows misinformation to be more persistent, continuing to propagate at low volumes after corrections have faded away,” they wrote.86

The researchers studied two other examples of misinformation that spread in the wake of the bombing. One example, which claimed the U.S. government had a role in the blasts, resulted in 3,793 misinformation tweets and 212 corrections.

The final false rumor study related to claims that Brown student Sunil Tripathi was one of the bombers. Regarding this, they identified 22,819 misinformation tweets and 4,485 correction tweets. This example was somewhat encouraging in that correction tweets eventually overtook the misinformation in terms of longevity, though certainly not in overall numbers.

When officials named the Tsarnaev brothers as suspects, the third rumor reached a turning point, according to the researchers. This served to amplify the trend toward correction that had begun prior to the announcement. “For this rumor, corrections persist long after the misinformation fades as users commented on lessons learned about speculation,” they wrote. This final example aligns with a common piece of advice offered to those trying to debunk misinformation: Present an alternate theory. In this case, the emergence of the Tsarnaev brothers as viable suspects helped blunt the spread of the Tripathi rumor.

Still, the Boston bombings research evidences that there are more tweets about misinformation than correction. Another recent paper examined whether misinformation and correction tweets come from the same people and clusters. Meaning: Do people who tweet (and see tweets with) misinformation also get exposed to the corrections? Unfortunately, they do not.

At the Computational Journalism symposium held in The Brown Institute for Media Innovation at Columbia University in late October of 2014, Paul Resnick and colleagues from the University of Michigan School of Information presented a paper about a rumor identification system called “RumorLens.” It included a case study that examined whether people who were exposed to a false rumor were also exposed to its correction.

They chose to study a false report about the death of musician Jay-Z. The researchers determined that 900,00 people “were followers of someone who tweeted about this rumor.”87 They found that 50 percent more people were exposed only to the rumor, as opposed to those who saw its correction. Overall, they concluded, “People exposed to the rumor are rarely exposed to the correction.”88 Moreover, they found that the audiences for the rumor and the correction were “largely disjoint.”89

A final data point comes from the previously mentioned Facebook study. Part of that research examined what happens to the spread of a rumor on Facebook after it has been “snoped.” Something is considered snoped when someone adds a link from Snopes.com to the comment thread of a rumor post. (The link could be debunking or confirming the rumor, as the rumor-investigating website does both.)

One encouraging conclusion in the Facebook research was that true rumors were the “most viral and elicited the largest cascades” after being snoped. However, the news was far less encouraging for false rumors and those with a mixture of true and false elements. The Facebook researchers found that “for false and mixed rumors, a majority of re-shares occurs after the first snopes comment has already been added. This points to individuals likely not noticing that the rumor was snoped, or intentionally ignoring that fact.”90

Misinformation is often more viral and spreads with greater frequency than corrective information. One reason for this is that false information is designed to meet emotional needs, reinforce beliefs, and provide fodder for our inherent desire to make sense of the world. These powerful elements combine with the ways humans process information to make debunking online misinformation a significant challenge, as I’ll detail in the next section.

The Debunking Challenge

Brendan Nyhan was hoping for some good news, but what he found was largely depressing. Nyhan is a professor at Dartmouth College who researches political misinformation and the attempts to correct it. He is also a regular contributor to The New York Times blog The Upshot and is a former contributor to the Columbia Journalism Review.

Some of his research has attempted to identify ways to effectively tackle misinformation. But Nyhan often ends up with findings that reinforce the painful truth: It is incredibly difficult to debunk misinformation once it has taken hold in people’s minds.

This was never more obvious than in a 2014 study Nyhan conducted in an area of persistent misinformation: vaccines. The study, published in the American Medical Association journal Pediatrics, tested different ways of communicating information about vaccines to more than 1,700 parents via a web survey. Participants were shown a range of information and content about the safety and benefits of vaccines, including images of children with diseases that are prevented by the vaccines, a narrative about a child who almost dies from measles, and a collection of public health information. The goal was to identify if one or more approaches were effective in convincing parents who are skeptical of vaccines to change their minds.

Now for the depressing part: Nyhan and his colleagues found that “parents with mixed or negative feelings toward vaccines actually became less likely to say they would vaccinate a future child after receiving information debunking the myth that vaccines cause autism.”91 When given the facts, in various ways, these people actually moved further away from vaccines. This behavior has been shown to happen time and again in research related to political issues and other topics. Present someone with information that contradicts what they know and believe, and they will most likely double down on existing beliefs. It’s called the backfire effect and it’s one of several human cognitive factors that make debunking misinformation difficult. The truth is that facts alone are not enough to combat misinformation.

The previous section of this paper examined the persistence and creation of misinformation and the failure to get corrections to spread. This section shows that even if we can tackle the challenge of making truth as interesting as fiction, we are greeted by another significant obstacle: our brains. Our preexisting beliefs, biases, feelings, and retained knowledge determine how we process (and reject) new information.

Our Stubborn Brains

There is, of course, a distinction to be made between information that speaks to deeply held beliefs, such as one’s political views, and information that doesn’t have as much at stake for the recipient. An example of the latter might be a viral news story about an Australian man who said that a spider burrowed its way into a scar in his chest while he vacationed in Bali.

Most people react emotionally to this story. It’s a powerful mixture of curiosity fused with disgust—and therefore highly shareable. But readers wouldn’t have a strong stake in whether it was true or not. They would presumably be open to subsequently learning that it was most likely not a spider in his chest, as that insect has never been documented to burrow under the skin. But there remain cognitive challenges.

One difficulty is that once we learn something, or have it stored in our brains, we are more likely to retain it intact. We like to stick to what we already know and we view new information within that context. “Indeed, social cognition literature on belief perseverance has found that impressions, once formed, are highly resistant to evidence to the contrary,” wrote DiFonzo and Bordia.92 Once we hear something and come to accept it—even if it’s not core to our beliefs and worldview—it’s still difficult to dislodge. “We humans quickly develop an irrational loyalty to our beliefs, and work hard to find evidence that supports those opinions and to discredit, discount or avoid information that does not,” wrote Cordelia Fine, the author of A Mind of Its Own: How Your Brain Distorts and Deceives, in The New York Times.93

Another complicating factor for debunkers is the way they’re received by the people they attempt to inform. If a person is harsh or dismissive in the way they correct someone, it won’t work. (Meaning: Chastising someone as stupid or gullible for sharing a false viral story is a bad strategy.) Tone and approach matter; the person being corrected needs to be able to let down his or her guard to accept an alternate truth.

Clearly, there are a lot of factors that need to be met (and overcome) in order to achieve effective debunking. I will examine those in more detail, and with suggestions tailored to newsrooms, later in this report. For now, it’s important to understand what we’re up against. Below is a look at seven phenomena that make it difficult to correct misinformation. Remember, again, that these barriers take hold when we’re able to overcome the initial hurdle of getting the correction in front of the right people.

The Backfire Effect

In a post on the blog You Are Not So Smart, journalist David McRaney offered a helpful one-sentence definition of the backfire effect: “When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.”94

This is what appeared to happen in the vaccine study, something that has been documented time and again.

McRaney delved further into the backfire effect in his book, You Are Now Less Dumb: How to Conquer Mob Mentality, How to Buy Happiness, and All the Other Ways to Outsmart Yourself. He offered this summary of how it manifests itself in our minds and actions:

Once something is added to your collection of beliefs, you protect it from harm. You do this instinctively and unconsciously when confronted with attitude-inconsistent information. Just as confirmation bias shields you when you actively seek information, the backfire effect defends you when the information seeks you, when it blindsides you. Coming or going, you stick to your beliefs instead of questioning them. When someone tries to correct you, tries to dilute your misconceptions, it backfires and strengthens those misconceptions instead.95

Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias is the process by which we cherry-pick data to support what we believe. If we are convinced of an outcome, we will pay more attention to the data points and information that support it. Our minds, in effect, are made up and everything we see and hear conforms to this idea. It’s tunnel vision.

A paper published in the Review of General Psychology defined it as “the seeking or interpreting of evidence in ways that are partial to existing beliefs, expectations, or a hypothesis in hand.”96

Here’s how a Wall Street Journal article translated its effects for the business world: “In short, your own mind acts like a compulsive yes-man who echoes whatever you want to believe.”97

Confirmation bias makes us blind to contradictory evidence and facts. For journalists, it often manifests itself as an unwillingness to pay attention to facts and information that go against our predetermined angle for a story.

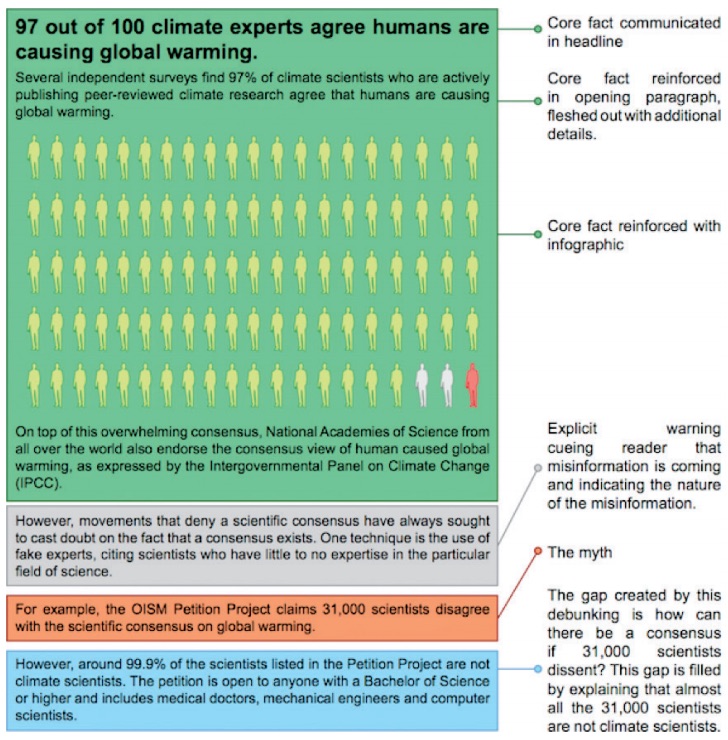

Motivated Reasoning