Yesterday, we published a report that explores journalists’ experiences with and views of newsroom social media policies. Below are six responses to the report written by journalists and media scholars. Each of these focuses on a specific issue raised in the report, including legal considerations (Victoria Baranetsky), online harassment (Michelle Ferrier), representation (Leonor Ayala Polley), audience trust (Benjamin Toff), objectivity (Laura Wagner), and solidarity (Jessie Shi).

Media Lawyers Should Defend Against Tweets, Not Just Lawsuits

By D. Victoria Baranetsky

Today media attorneys are focused on the rising number of lawsuits that threaten their reporters from telling truthful stories, but the threats that we should be most concerned about are those that our journalist colleagues face online.

In 2017, Mackenzie Mays, a Politico reporter who formerly worked the Fresno Bee, published an article that quoted the Fresno Unified School Board President’s disdain of California’s sex-ed laws. After public alarm ensued, the Board President lashed out at Mays, calling her “fake news” and the “ministress of propaganda.” He then put Mays’s phone number on Facebook and encouraged others to go to her house—emboldening an army of trolls to threaten her safety both online and offline.

The next year, Mays wrote a separate story about a lawsuit alleging that a charity fundraiser on a yacht devolved into a debauch with drugs and prostitution. Mays reported that the cruise was sponsored by a winery in which Devin Nunes, a California congressman, is a limited partner.The article did not state that Nunes was on the boat and clarified that it’s “unclear” whether Nunes was affiliated with the event. And though Nunes did not respond to a request for comment, the Congressman filed a lawsuit for $150 million in damages.

Immediately after the story ran, Nunes accosted Mays online, in television ads and a 38-page mailer that condemned Mays and contained a photo of her. After both of these backlash events Mays weathered exceptional vitriol, including specific violent threats made against her family members.

Mays shifted my perspective on what constitutes a threat in the field of journalism. I heard her speak about these harrowing events on a panel in 2019 covering threats in journalism, where I also delivered a speech. While my remarks warned against the rise of lawsuits brought against newsrooms, Mays’ experiences made me realize that paper filings might not in fact be the most pressing danger to journalism.

In 2019, Mays won the National Press Club’s John Aubuchon Press Freedom Award. The president of the National Press Club Journalism Institute heralded Mays as “the best of local journalism.” She continued, “Mays persevered in the face of an anti-media scourge that is now all too common: online trolling, nuisance lawsuits and implied or direct threats. We have sometimes seen such verbal smears transform dangerously into physical attacks and even murder.”

But while Mays’s endurance of vitriol may represent the best of journalism, a question remains: does the profession of journalism return the favor to Mays, and others like her? As Jacob L. Nelson’s paper, “A Twitter tightrope without a net: Journalists’ reactions to newsroom social media policies” aptly asks “What do the newsrooms do to help? What structures were in place to offer support?”

To the Bee’s credit, its editors published statements condemning the threats against Mays. But what Mays’ story highlights—and Nelson’s report underscores—is the crucial question of what more could have been done? Why didn’t the newspaper fight back with legal action against the harassment? Why didn’t the paper prepare Mays for this possibility?

As Nelson’s report accounts, these questions have still not been answered since Mays was attacked; in fact, they’ve only become more persistent. Nelson lists numerous incidents of harassment online. In my own experience, as a general counsel of a nonprofit newsroom, Reveal, I have seen online harassment increase by multiples. At the same time, Nelson’s research shows that most media companies’ social media policies tend to narrowly focus on how journalists “should—and should not—behave” online but do not address “how journalists should grapple with the risks and challenges that social media presents, and what resources (if any) newsrooms make available to help them.” Nelson’s interviewees suggest that social media policies “need to build in protections for journalists,” by emphasizing “what you’re maybe going to be experiencing and getting back, whether it’s harassment, whether it’s threats, whether it’s a concerted smear campaign.” And by failing to do this, as one editor told him, “Reporters are usually on their own when it comes to trolls.”

But one additional question Nelson’s report does not consider is: What role media lawyers should play? Media lawyers often think of themselves as the main line of defense for journalists. We are often vigilant about cease and desist letters and lawsuits, as powerful figures routinely and more frequently threaten legal action to squelch critical reporting. But our profession is not as engaged on the question of how to defend reporters against threats made against them online—even while those threats are perhaps more effectively silencing the press.

This question is especially crucial as reporters, especially female reporters, are seeing more of these intimidations on a daily basis. Just this year, the newsroom I work for, Reveal from The Center for Investigative Reporting, has dealt with multiple threats made to reporters online. In response to this trend, Reveal now institutes a threat assessment to stories that could spur online backlash prior to journalists even engaging in the investigation. Editors and legal counsel now try to speak with reporters before their investigation begins about the possible risks that they might face, even long after publication, in order to prepare them and preemptively protect them from these dangers. For instance, journalists about to embark on contentious investigative subjects, like abortion or gun violence, are now encouraged to sign up for programs that delete personal information online. Reveal also has guidelines to follow once a reporter is harassed.

As newsrooms begin to engage in this proactive process, in-house lawyers should think to do the same, especially as tweets are becoming ever more the subject of libel litigation. This past month, a federal appeals court rejected Nunes’s defamation suit against Hearst. (This is a different lawsuit from Nunes than the one involving Mays.) But at the same time, the court revived Nunes’s claim that he was libeled when a reporter tweeted out a link to the story.

The United States Court of Appeals stated that when reporter Ryan Lizza tweeted out a link to his story, published in Esquire, Nunes had already filed a defamation suit over it and so Lizza republished facts knowing that there was a denial. Therefore, the court said, Lizza showed evidence of actual malice, the standard developed in the Supreme Court that requires a reporter who knowingly publishes false material about a public figure to face liability.

Hearst, which owns Esquire, along with a coalition of other media groups have submitted briefs to challenge this decision. Setting aside whether hyperlinking counts as a republication for a defamation claim, which courts have almost unanimously decided it does not, this decision reaches another disturbing conclusion: that courts can look to tweets to determine a reporter’s intent––including even the timing of the tweet.

The fact that tweets can lead to litigation is not a new development. Back in 2009, Courtney Love was the first person sued for defaming someone in a tweet. By 2011, in a now-decade old article (that now reads like a relic of the late aughts), Poynter concluded that tweets “could have legal implications” for a newsroom. But at that time most newsrooms were merely concerned with the content of the tweet resulting defamatory statement – but not going to the intent of a reporter. The Hearst case shows that now any circumstantial facts about a tweet can be used in a lawsuit – even when the tweet was tweeted and even to show a reporter’s intent.

While Nelson’s article stresses that reporters wish to speak openly on Twitter journalists must know that today, powerful actors are using every mechanism they can to intimidate the press – and tweets are now evermore a part of the litigation strategy. As was done in the Hearst case, a journalists’ tweets are often scoured to be used in lawsuits to develop evidence of actual malice. A journalist’s social media account can open them up to attacks online, in the court, or even in person. Those 280 characters can have consequences. But this should not dissuade reporters from using social media, or silence them from sharing the truth.

Instead, newsrooms’ lawyers, alongside security experts, should create training sessions that exclusively cover tweeting and social media, to explain how these tools can be used safely, and how they can conversely be wielded to injure a reporter. Media lawyers should catalog the harassment the newsroom suffers and should empower journalists by reviewing tweets and explaining what reporters should do when they become a recipient of harassment, including creating a log of incidents. But most important, these trainings should convey that newsroom lawyers “would have [journalists’] backs” by “stepping in when harassment escalates,” and “responding to or reporting bad actors,” as Nelson similarly suggests for newsroom management. Because to do otherwise might continue the sin of normalizing harassment as “a rite of passage.”

Failing to act would otherwise fail to accurately identify Mackenzie Mays, and other reporters like her, as what they are: extraordinary. Mays’s response and ability to endure her trauma were not and should not be heralded as ordinary or expected. Female journalists and journalists of color should not ‘tough it out’” when being targeted. They should have an army of management and lawyers helping guide them through the hazardous landscape of bullies that threaten them from sharing the truth.

Victoria Baranetsky is general counsel at The Center for Investigative Reporting, where she counsels reporters on newsgathering, libel, privacy, subpoenas, and other newsroom matters.

Social media policies put journalists at risk

By Dr. Michelle Ferrier

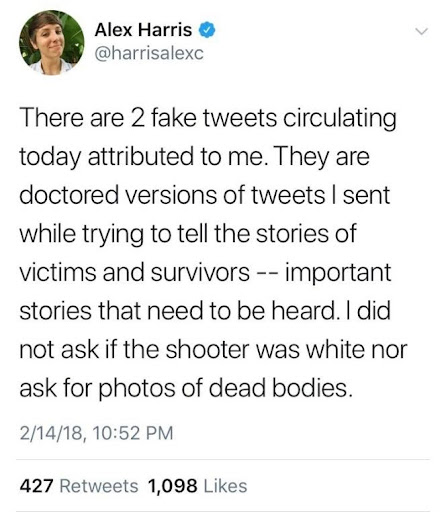

Alex Harris, a journalist with the Miami Herald, reached out using social media in the aftermath of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School attack on February 14, 2018. Like many journalists, social sourcing is critical to her work, especially in breaking news scenarios, Harris said in an interview with NPR. “Twitter is where you reach out to people who are self-selected saying, I’m in this situation, I am in a place where I can say something on social media.”

She sent a tweet calling out for sources. And the dark Web sent back an altered version, suggesting that Harris was inappropriately soliciting the racial identity of the shooter from witnesses. The doctored tweets went viral.

Fellow journalists jumped into the Twitter swarm and amplified Harris’s call that she was being impersonated through the doctored tweets. Others offered emotional support against the barrage of outrage coming at Harris. Some helped to explain that Harris’s tweet is a part of how journalists work. Others reported the more insulting and aggressive tweets.

The imposter tweets had achieved their objective––to cast doubt on the credibility of a journalist, to chill her ability to her job, and to discredit the reporting coming from the Miami Herald. And according to Harris, the tweets diminished the overall reporting efforts of her team, impeding their ability to tell the story.

By 2010, journalists sought to create more intimate, authentic portraits of themselves, using their personal and professional accounts to build their online reputation. Journalism textbooks encouraged students to “build a personal brand.” Social media follower counts became a metric in newsrooms for measuring reach into new audiences and encouraging new readers and subscribers. Social influence could garner a journalist lucrative television appearances as media pundits, or even a new job.

One journalist I interviewed at a global media company said it this way:

“There are certain people…I don’t have an agenda. A self-promotion agenda. I’m not trying to get a CNN gig. And it’s a different industry than it was in the past. You have to build up a personal brand more.”

As journalists’ work migrated onto digital platforms to reach audiences, online harassment followed, using the anonymity, speed and distributed nature of the internet to mount swift, coordinated campaigns. And recent research from Marjan Nadim and Audun Fladmoe found that targeted women are more likely than targeted men to become more cautious in expressing their opinions publicly. As the harassment becomes more aggressive and directed toward group characteristics, they found, gender differences increase.

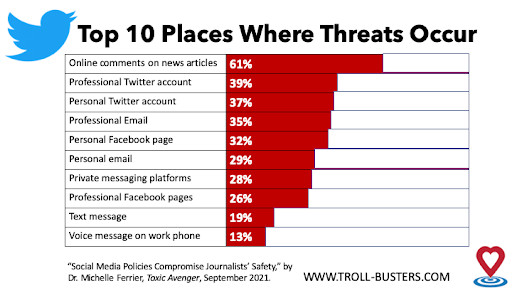

While social media tools like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram have been the primary vector of digital attacks, they can manifest in a variety of ways. According to research by TrollBusters (www.troll-busters.com) , online threats tend to occur most in the online comment sections on news articles (61 percent), followed by professional Twitter accounts (39 percent), then personal Twitter accounts (37 percent):

From professional critiques to insults, doxing to death threats, I found that journalists were fielding threats on multiple platforms and of varying severity. Online attacks frequently reference personal features or family and personal relationships. Many of the threats women journalists receive online are sexist in nature, designed to intimidate or shame the journalist. Gendered attacks seek to discredit women journalists, damage their reputations, and ultimately silence them. Journalists of color receive some of the most racist and violent types of harms, with sustained activity on multiple platforms. Perpetrators of these physical and online threats operate for the most part with impunity, leaving individual journalists to navigate how best to respond.

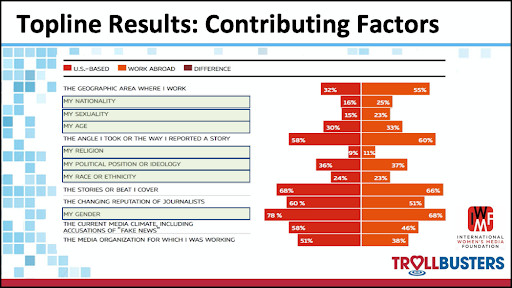

In my research work, journalists identified the following contributing factors—both professional and personal—as to why they believe they are under attack. Top factors for journalists both in and outside the US include gender at 78 percent of respondents, followed by political position or ideology (36 percent), then age and race or ethnicity (24 percent).

Social media policies of media organizations have not kept pace with the growing hostilities of “fake news” and “enemy of the people” and eroding trust toward journalists in digital spaces. Social media policies often put journalists directly at risk by blending personal and professional identities. And journalists don’t feel supported or their concerns addressed when they bring these issues and threats to management.

The social media policies of media organizations leaves little guidance for journalists on what to do if they become the target of an attack. My review of the social media policies of some media organizations shows the conflicts inherent in their guidance:

- Most publications encourage journalists to have social media accounts––to promote the publication’s work, add to the organization’s digital presence, and increase the brand credibility and trust.

- Journalists have to stay in line with the publication’s values on social media, social media policies apply to public and personal accounts.

- Under no circumstances are they allowed to post, like, or retweet anything taking a side.

- However, media organizations don’t provide concrete advice on dealing with online abuse.

This social media abuse has consequences for the individual journalists and the news business at large. Recent reports of burnout and mental health issues in the journalism profession point to the long-term effects of online harassment on journalists. Online threats also have a chilling effect on the news enterprise, slowing or preventing journalists from doing their work. As individuals, journalists may not be able to “get off of the internet” or adjust privacy settings as they may need to maintain that public presence for their jobs. And while the exact relationship between online harassment and staff churn is unknown, dealing with online harassment on an ongoing basis can contribute to higher burnout rates, staff turnover, and long-term censorship of lines of investigation.

Some journalists experienced professional or social retaliation (33 percent) for reporting these online harms to management. Others report being blamed for the situation or being denied promotions. Some journalists have been taken off their beat or fired for violations of social media policies (8 percent).

In my 2018 survey, I asked our respondents how they respond when attacked or threatened in person or online. Two-thirds share the event with a family member, friend or colleague. More than half will use blocking tools on the offenders. Nearly one-third have reported threats and attacks to social media platforms. Others personally replied to the harassment, either publicly (28 percent) or privately (34 percent). However, more than one-third of our respondents had never reported their abuses to management (35 percent). A significant number of respondents did not report the abuses to management for fear of retribution or punishment. Nearly one third (29 percent) indicated that they feared retaliation/reprisals from the persons who initiated the attack, and an equal number feared they would be taken off their beat or lose future work.

Fifty-six percent indicated that they didn’t think anything would be done, and that is why they did not report to management. Twenty-six percent indicated they didn’t know how to report the threats. More than a third said they felt uncomfortable making a report or they felt that they would be labeled a troublemaker. Another 29 percent indicated they had heard of negative experiences of others who had reported their threats to management. While not widespread, some respondents reported retaliation in the workplace—19 percent indicated they experienced social retaliation from coworkers, and 14 percent reported professional retaliation where they were removed from their beat, lost privileges or were denied a promotion.

For women journalists and journalists of color, these attacks serve a double blow––to their private lives and to their professional mobility. In our survey, nearly 29 percent of respondents indicated the threats and attacks they received made them think about getting out of the profession. However, when we examine the data by age, early-career journalists (ages 18-29) are nearly twice as likely (36 percent) to have considered getting out the profession as their older colleagues, ages 40 and older (18 percent). Another 24 percent indicated that their career advancement had been negatively impacted. As a result of harassment, respondents told us, they engaged in self-censorship when going about their work: 37 percent indicated that they avoided certain stories and another 23 percent indicated they had trouble establishing rapport with interviewees.

Journalists around the globe are currently in the crosshairs of bad actors online, creating a hostile work environment that chills press freedoms and silences individual journalists. While social tools like Twitter and Facebook can be used to broaden and improve reporting, the boundaries between personal and professional identities continue to blur. How can journalists protect future job opportunities from their tweets of today? How can they continue to call out authority while protecting their online impartiality? How can they engage controversy without becoming the story? News organizations must urgently engage in these debates.

Dr. Michelle Ferrier is the founder of TrollBusters, www.troll-busters.com and executive director of the Media Innovation Collaboratory, www.mediacollab.org.

Diversity is not enough. Management must empower journalists of color to speak up.

By Leonor Ayala Polley

As a veteran social media manager, Micah Grimes gives the same advice to everyone: “Social media is the fastest way to grow your own brand—and the fastest way to get fired.”

Journalists are asked to both be active on social media and uphold traditional principles of objectivity. It’s a double-edged sword—one that women and journalists of color have been discussing for years. How are social media policies in newsrooms shaped and by whom? Who has a seat at the table during these discussions? Who are these policies designed to protect? Is there room to protect both the brand’s integrity and the journalists on the frontlines of the social media battlefield?

Jacob Nelson’s “A Twitter tightrope without a net: Journalists reactions to newsroom social media policies” lets readers in on the often-secretive discussions that shape industry policies. The report shows how these social media guidelines are rife with contradictions that often leave women and journalists of color exposed to an uneven enforcement of the rules.

One journalist recommended to Nelson: “Hire more women journalists and journalists of color, and give those journalists the agency with which to not only shape the social media policies of their organizations, but to contribute to larger discussion surrounding the values of those organizations as well.”

It is this latter part that resonates. It is simply not enough to have one or two diverse voices helping to shape an organization’s policies. Representation does not always equal equity and inclusion, nor does it have the power to remove barriers. I have seen women and journalists of color be “in the room where it happens” without true power to influence change. In fact, I’ve been in that position myself. While most newsrooms encourage employees to speak up, dissenting or challenging views are not always welcome.

“I was told [by Senior leadership] not to continually post about what was happening in my home country of Venezuela, even though those stories weren’t being published or broadcast on any other mainstream platform, which I found very dejecting,” said Mariana Atencio, a television host and former correspondent for MSNBC and Univision. “The more I spoke out to point out flaws and biases in the system, the more protected I felt. I would tell young journalists to speak up!”

Atencio has 65,000 followers on Twitter and has been the subject of barrages of social media attacks. She says that she didn’t feel that her employers supported her, in large part because they simply did not know what to do. Her bosses were largely white and practiced journalism at a time before social media.

“Senior leaders need to include the upcoming generation, as well as diverse journalists who truly understand these platforms to draft the newest handbooks and as consultants on their ethics, social media and talent departments,” Atencio said.

In some news rooms, there are no diverse senior leaders at the table to participate in these discussions at all. A 2019 American Society of Newspaper Editors diversity survey, found that just 18.8% of all print and online newsroom managers were people of color. A RTDNA 2019 survey shows that only 17.2% of TV news directors and 8.2% of radio news directors were people of color.

Most newsrooms have pre-existing social media policies and guidelines that are refreshed as needed by a standards and ethics department. New hires and employees will train on those rules as part of the onboarding process. But journalists rarely have the opportunity to shape the rules they need to live by.

Grimes, who is currently the VP of News at Atmosphere TV, has guided high profile on- and off-air talent through doxing, trolling and other forms of online harassment. “If you’ve never experienced a targeted attack on social media, it’s hard, if not impossible, to understand and appreciate the overwhelming helplessness and anxiety mentally, and sometimes, physically,” he said. Grimes said he saw women bear the brunt of online harassment and attacks. He also added that it was a reporter who enlightened him on how he could offer better support as a leader. “You’re dealing with peoples’ lives. Improving response should be a top priority always.”

Guidelines that currently feel opaque or haphazardly enforced will become more tangible and manageable for both senior leaders and journalists alike when these policies are shaped by a panel of newsroom employees who are likely to face the consequences of any missteps. Detailed rules about enforcement and a transparent process that ensures equal enforcement is critical to retaining talent of color.

Diverse voices with the power to enact necessary changes and revisions to policies will help create safe spaces that ensure the safety—physical and mental—for all journalists. Newsroom leadership would be best served by including a variety of stakeholders across the newsroom who possess diversity of thought, and experience- both in life and professionally in their decision-making about social media policy.

Leonor Ayala Polley is the head of audience development/recruiter at URL Media. She previously led the strategic expansion of NBC Universal Newsgroup’s flagship learning and development programs centered on newsroom diversity -on-air and off-air.

Does the way journalists present themselves on social media reduce audience trust in news?

By Benjamin Toff

Jacob Nelson’s report does a commendable job drawing attention to the “Twitter tightrope” that many journalists, especially women and journalists of color, increasingly find themselves walking in the US and abroad. While engagement with audiences on social media platforms has long been viewed as desirable for expanding reach and building trust by deepening relationships with readers, it also comes with indisputable professional, reputational, and mental health risks—consequences that newsrooms focus on selectively (if at all) while holding their own employees to standards that are unevenly and sometimes unfairly applied.

The report includes several much-needed and overdue recommendations. Among them is the common-sense notion that news organizations ought to have clear-cut, standard operating procedures for protecting employees from toxic and threatening harassment online. Furthermore, as Nelson writes, the industry as a whole should seriously consider normalizing the practice of not using Twitter at all. The centrality of the platform to American journalism is more about the industry’s self-infatuation than it is about meaningful engagement with audiences; only a small fraction of the public—just 13 percent of Americans, according to the Reuters Institute’s 2021 Digital News Report—uses the platform for news.

One of the recommendations in the report, however, does give me some pause: the idea that newsrooms might consider deemphasizing concerns about objectivity when it comes to their own social media policies. While there are many reasons why transparency generally ought to be championed for its own sake, newsroom leaders are not necessarily misguided to worry about perceptions of violations of objectivity. Certainly growing numbers of journalists (and academics) offer compelling arguments around why traditional notions of objectivity should be revised or replaced—especially those more performative aspects that invite false equivalency and other problematic practices. However, even the appearance of bias can be highly damaging in an environment where news audiences are already predisposed to think the worst of journalists. There is immense value that comes from a brand being seen as “fair and balanced,” whether that brand is Fox News or the BBC, and while many journalists feel trapped when it comes to maintaining a veneer of detached impartiality online, the trade-offs around lifting that veil ought to be taken seriously.

I offer this assessment with a great deal of humility. There are no simple solutions here, and there is much more that we do not know about the impact of social media disclosures from journalists on audience perceptions of news. Below, I highlight three main findings based on research from an ongoing project on trust in news that I have been conducting with a team at Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. This project has afforded me some modest insights into how some audiences think about the questions raised in Nelson’s report—although, as I note in my conclusion, there are many limits to constructing newsroom policies based solely on what audiences say they care about without knowing more about what they actually do.

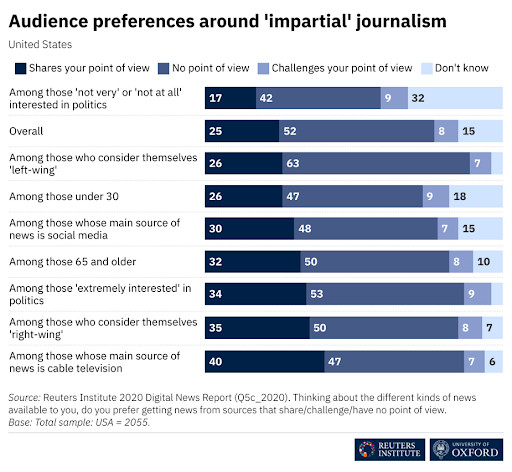

- There is limited appetite for news that deviates from traditional standards of objectivity

Most news audiences overwhelmingly continue to say they prefer “objective” news, free from bias or a “point of view.” This is true in most countries, including the US, where impartial or objective news is favored by a more than two-to-one margin over alternatives. In 2020, the Reuters Institute included a question on its annual Digital News Report to capture people’s preferences around purportedly neutral approaches to news reporting compared to alternatives. The question asked respondents whether they preferred sources of news which shared their point of view, challenged it, or had no point of view at all. The question is far from a perfect encapsulation of the idea of objectivity—after all, many people have different notions of what news with “no point of view” actually means. (That becomes very clear when you actually converse with people on the subject, as we did in our second report.) But responses in most places around the world are similar. Most people are averse to forms of news that deviate from its most neutral form.

Those in the US who are most likely to say they prefer news aligned with their point of view are not necessarily the left-leaning critics of news who are particularly outspoken on social media. Instead, it is older, more right-leaning, cable television viewers who are most likely to gravitate toward like-minded journalism. This point is worth keeping in mind when considering approaches that deemphasize objectivity online. It may be a more satisfying approach to a few highly engaged news junkies, but it runs the risk of alienating many more.

We investigated some of these expectations further in our research this year on trust in news, which also showed broad agreement (80 percent of respondents) that journalists should “separate fact from opinion when reporting the news.” A majority of people in the US who often used social media for news agreed that journalists should even go so far as to disclose their political leanings (56 percent), although a smaller share of the public overall felt the same (45 percent).

- Audiences are already highly attuned to seeing bias in most things journalists do

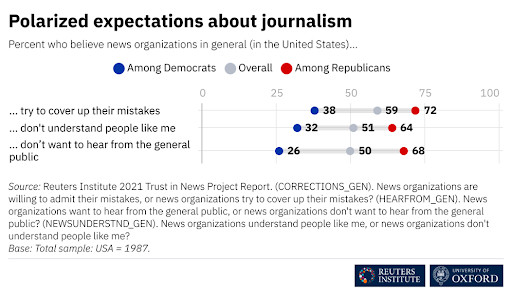

Levels of cynicism about journalism in the US are not only high—they are exceptionally polarized along partisan lines. This year, when we asked Americans whether news outlets in general were willing to admit (or cover up) their mistakes, whether they understood their audiences, or whether they genuinely wanted to hear from the public, a majority held negative views on all three measures. Even more striking, responses to these questions were highly polarized by partisanship, with two-thirds or more of Republican-leaning respondents holding journalists in low esteem.

What’s more, audiences held generally low expectations about whether other basic tenets of objectivity were typically upheld. Eighty-six percent of Republicans and 72 percent of Democrats thought journalists sometimes or very often allowed their “personal opinions to influence their reporting.” Similar percentages said the same about how often journalists “try to manipulate the public” (81 percent of Republicans and 67 percent of Democrats) or “get paid by their sources” (78 percent of Republicans and 63 percent of Democrats). Given this already wide gulf between the public and the press, transparency around journalists’ subjective viewpoints may not be widely embraced.

- Audiences are more interested in knowing about how journalistic decisions are made than the backgrounds of individual journalists

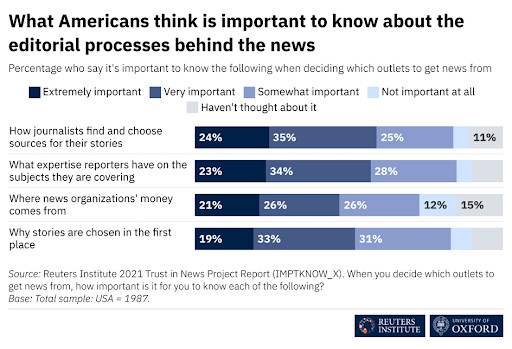

In our most recent report, we also asked a separate set of questions around what audiences paid attention to when differentiating between news outlets. While the least trusting were most indifferent toward knowing more about, for example, how journalists find and choose sources or why stories are chosen in the first place, a majority of Americans said such matters were important to them. Agreement on these measures was even higher among those who said they often used social media to get news.

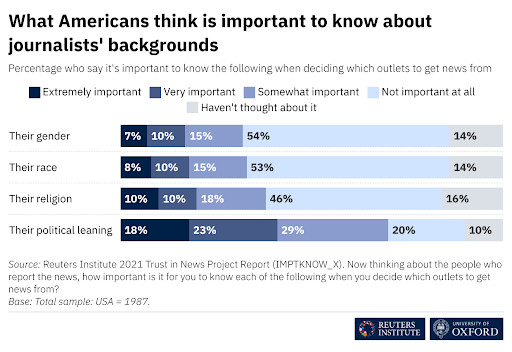

As a point of comparison, audiences said knowing about journalists’ backgrounds—their race, gender, religion, or political leaning—was generally less important.

How worried should news organizations be about journalists’ presence on social media?

We cannot know based on these responses alone how important these characteristics really are to the way news audiences think about objectivity. On the one hand, survey responses suggest that audiences are more interested in the substance of reporting practices than the subjective perspectives of individual journalists. This is likely true in general, but there are strong social desirability biases here. The experiences of individual journalists captured in Nelson’s report tell a somewhat different story, on the other hand. Clearly some portion of the public (if not most people) see engaging with journalists on social media as an opportunity for targeting them with abuse, not as a chance for engaging in open dialogue with three-dimensional human beings.

Political science research has long shown how voters often make assumptions about the ideological leanings of candidates on the basis of their gender, race, and other characteristics, and news audiences almost certainly do the same. That means people likely hold journalists to different standards on the basis of their backgrounds—even if they disavow doing so in surveys. This tendency undeniably puts women and journalists of color in a bind: the mere fact of their identities invites some audiences to see them as ideologically compromised while their white male colleagues’ backgrounds are more often treated as neutral by default. This dynamic is extraordinarily unfair, but ignoring it does not make it go away.

There are clear risks for both individual journalists and news organizations when engaging with audiences on social media, and the burdens associated in doing so are disproportionately shouldered by some far more so than others. News organizations do a disservice to their own employees when they do not adequately acknowledge and grapple with this problem, even if they are rightly worried about placing a premium on their brand’s reputation for impartiality.

Benjamin Toff is a senior research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the study of Journalism and the University of Oxford. He is also an assistant professor at the Hubbard School of Journalism & Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota.

Who is ‘objectivity’ meant to serve?

By Laura Wagner

The debate about journalistic objectivity is an unwieldy thing. At its most confused, it attempts to contend with squishy questions about the nature of truth itself. At its most useful, it is concerned with the practical matter of reporters and editors doing the most effective and transparent journalism they possibly can. “A Twitter tightrope without a net,” Jake Nelson’s Tow Center report on newsroom social media policies, largely focuses on the latter.

Nelson’s report, based on interviews with three dozen media workers, details how newsrooms attempt to provide their audiences with an image of journalistic objectivity by controlling—and unevenly enforcing—what their workers can and cannot express on social media platforms like Twitter. The report begins to differentiate between the various definitions and interpretations of journalistic objectivity. As Gabe Schneider, journalist and co-founder of The Objective, said, there is the “objectivity of self” (an awkward goal that deals haphazardly with what it means to be a reporter and a person) and “objectivity of practice” (a worthwhile goal that deals with the reporting process). Additionally, the report clearly lays out how such social media policies hold journalists of color and women journalists to different standards, and how the same policies are primarily concerned with protecting institutions and the power of those who oversee them—not the journalists themselves.

The report concludes by suggesting ways newsrooms could change their approach to social media policies to improve the quality of their journalism and the working conditions for their employees. Among the suggestions—some of which, including the creation of more democratic systems, would be of immediate practical use in most newsrooms—is that institutions and journalists should prioritize transparency with regard to both the reporting process and individual reporters’ opinions over vague notions of objectivity, an approach that engages many of today’s thorniest problems within journalism.

Before attempting to tackle the idea of journalistic objectivity, it’s important to understand where it came from in the first place. While today’s conventional thinking assumes that journalistic objectivity is an inherent, natural feature of the American press, there is actually nothing natural about it. In fact, for much of American history, newspapers staked out partisan positions and provided pointed analysis as a matter of course. The notion of journalistic objectivity—the broad idea that it is 1) possible and 2) beneficial to cleave facts from certain contexts, analyses, and opinions—didn’t become popular until the early 1900s. And it didn’t arise from any principled consideration of the essence of information and democracy, but from those with power observing a raw economic reality. Newspaper consolidation in the 1920s meant there were fewer papers providing news to readers. Fewer papers meant that each one served, or had the potential to serve, a larger portion of the market. As a result, newspapers were incentivized to adopt a pose of neutrality, lest they risk turning off chunks of potential paying customers, be they readers or the companies trying to advertise to them. This concern for the bottom line led news organizations and reporters to take a “just the facts” approach to journalism. And despite the many well-documented failures of “objective” journalism over the decades, as well as numerous cycles of rebellion against the objectivity regime, these same market concerns, and an ever-consolidating media landscape, continue to animate the fight to preserve the status quo.

This position is reflected in the report. Under the heading “Upholding traditional notions of ‘objectivity,’” several journalists critiqued repressive social media policies that “presume that it is possible for any one person to ever be truly objective about anything.” The report continued:

To be sure, others I spoke with disagreed […], and felt that audiences indeed want their news to be delivered by journalists who do not broadcast their political views, especially if those views run counter to their own. [Now-former McClatchy editor Cal] Lundmark, for example, described how she had started using phrases like “gun rights” instead of “gun control” and “abortion legislation” instead of “reproductive rights” when she began doing audience growth and retention work for McClatchy’s southeast newspapers.

“It’s the same story. It’s the same reporting, but it’s going to be framed in a way that makes that news accessible to our readers,” she said. “Everyone in our community doesn’t necessarily agree with us, and we have to serve those people too. That’s when a really good audience team will come into play.”

It’s unclear what about the phrasing “gun rights” is more “accessible” than “gun control,” especially when set up against the other example that casts “reproductive rights” as less “accessible” than “abortion legislation.” Objectivity in this context, it seems, means saying whatever it is that doesn’t alienate the greatest number of audience members. (What’s not made explicit is that news organizations need an audience in order to earn revenue in order to stay in business.) This seemingly innocuous word choice is also rather insulting to the very people who Lundmark is supposedly serving, implying as it does that these hypothetical readers would be unable to “access” a news story if the framing didn’t precisely cater to their ideological positions.

The assumption that audiences want their news to be delivered by journalists who do not broadcast their own political views also merits a citation. The report says:

As Lundmark’s examples make clear, these policies—and their underlying notions of objectivity—stem not just from norms and values within journalism, but also from assumptions among journalists about what the public wants from news. And social media policies by and large tend to imply that audiences will abandon news sources if the journalists working at those sources reveal that they have perspectives or opinions that run counter to prevailing notions of objectivity.

“We have readers who have been with us forever, and this is their paper,” said [former audience engagement editor Nikki] Naik about the State newspaper in South Carolina. “This is their home paper, and I think they have developed this sense of trust. We get comments from our readers saying, ‘What agenda are you trying to push here?’ But that doesn’t mean we should feed into it, right? Just because they think that doesn’t mean we should just say, ‘Yeah. You’re right. Let’s just keep going with it.’ No. We’re going to give you both sides. That’s our job at the end of the day.”

At the end of the day, a newspaper’s job is two-fold: to inform its readers about the reality of what is going on in their communities (not to shy away from it in order to preserve its audience), and to help readers make sense of the world (which often is not the same thing as giving “both sides”). By Naik’s own account, it seems readers do want to know where reporters and editors are coming from when they publish news stories. With that in mind, the report’s suggestion that “newsrooms should pin their credibility on the process of the journalism itself rather than on the type of person that is doing the journalism work” is perhaps the most useful.

Whether any of this is possible on a grand scale in the current media landscape, which has been shriveled by Facebook and Google and gutted by private equity, is an open question. But the ongoing reconsideration of journalistic objectivity is related to that question. Because, as evidenced in the report, it’s clear that the objectivity regime functions as a bulwark of the status quo, preserving and protecting hierarchies within and journalism and without.

Laura Wagner is a reporter and co-owner at Defector, where she covers labor and media. She previously worked at Vice, Deadspin, and Slate.

A more supportive newsroom social media policy starts with us standing up for each other

By Jessie Shi

What can newsrooms do to help journalists facing threats and harassments on social media? What structures are in place to offer support?

When Jake Nelson asked me these questions. I believed that trolls and threats on social media affect journalists’ mental health, but I had never thought about how newsrooms could offer support. “Reporters are usually on their own when it comes to trolls,” I said while acknowledging that these questions are great food for thought.

Jake’s report provided some relief, but also concern. Relief because I knew I was not the only one who needed to take breaks from social media. It was tough to read about the deaths of COVID-19 patients, misinformation about public health, the 2020 presidential election, and hate crimes against Asians and other racial and ethnic groups. Concerned because abuse and harassment are so common among reporters, especially journalists of color like me.

I have been fortunate to work with caring and supportive managers in my professional career. My gratitude to them is beyond words. An updated social media policy matters, and nothing else can replace it. But even a few kind words from managers and other colleagues go a long way.

Just reading about hatred and violence on social media can still hurt, but newsroom managers can support journalists before trolls reach their direct messages, tweet replies and Facebook comments.

The hate crimes against Asian communities in mid-March took a toll on my mental health. A San Antonio restaurant was vandalized with messages including “No Mask,” “Hope you Die,” “Go Back 2 China” and “kung flu.” Two days later in Atlanta, a gunman killed eight people in several spas. Six of the victims were Asian women.

It was gut-wrenching to see a series of violent crimes hit my own community in just three days, and promoting those heartbreaking stories on social media meant reliving those traumatic moments. As the only social media editor for the San Antonio Express-News, I felt obligated to tell the stories, stay mentally strong and help unite the Asian community. As a human, I felt the negative impact from reading about hate crimes on social media. It affected my productivity at work. It usually took me a few minutes to read a story and craft a tweet and Facebook post. It took me half an hour or longer on those days. But a few kind words from my former manager, Randi Stevenson, made a big difference.

“Jessie – I’m so sorry about everything happening in the Asian community. It’s awful, and I hope you never have to experience anything like it in San Antonio. Don’t hesitate to reach out if you need anything – some time to talk to, info on the Hearst* mental health program (which a lot of people in our newsroom have taken advantage of!). Just know we’re here for you 🙂

And know that we’re all ears if you have ideas/thoughts/concerns on our coverage. You’re a valuable voice in the newsroom,” she wrote in a Slack message to me.

I choked up when I read it. Asians account for less than 3 percent of the total population in the area. I enjoyed working with everyone on my team, but I didn’t expect anyone to send their thoughts. In fewer than 100 words, my former manager recognized my feelings, told me she and the rest of the team were there for me, mentioned helpful resources and showed appreciation for my work. After I read her message, the fear and anger I had been overwhelmed with was replaced by love, care, and support. When hatred and harassment crush reporters, support from managers and other colleagues can renew feelings of strength and empowerment.

We still need to address in our social media policies how to deal with online harassment and what newsrooms should do to support journalists, but we don’t have to wait for the updated policies to stand up for each other.

I feel grateful for the support and encouragement I received. I also feel sad that they seem to be the exception rather than the rule. As Jake wrote in his report, journalists wished more than anything else that their newsroom managers would have their backs. To make newsrooms obliged to protect journalists from trolls, we need to update social media policies and develop mandatory training in dealing with online harassment. That starts with addressing real-life examples of how journalists experience harassment and abuse and what newsroom managers do to support them.

There is no easy answer, but supporting each other is an important step forward. Address any harassment and abuse we receive on social media. If our colleagues are the victims, express empathy, mention helpful resources, and show appreciation for them in emails or direct messages. We need to share these situations to our managers and teams and suggest that our cases be included in updated social media policies and training.

Chinese philosopher Laozi said “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Developing procedures to protect journalists from trolls will take time, patience, wisdom and tenacity. Jake’s report has points us in the right direction. Let’s take that first step toward a more protective, supportive, diverse, and inclusive journalism community.

*Hearst is the parent company of the San Antonio Express-News.

Jessie Shi is a social media editor for MarketWatch. She previously was the social media editor for the San Antonio Express-News.

Tow Center provides journalists with the skills and knowledge to lead the future of digital journalism and serves as a research and development center for the profession as a whole.