Executive Summary

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a major piece of EU legislation that will transform the operating landscape for any organization that handles data about EU residents. While the regulation, which goes into enforcement effect on May 25, 2018, will have the greatest impact on technology companies and advertising networks that directly monetize user data, the media companies that often depend on them for both reach and revenue will also be significantly affected by the changes it brings—both directly and indirectly.

The goal of this report is to provide an overview of the regulation and its likely impacts for news organizations and publishers with primary audiences outside the European Union. Unlike its predecessors, the GDPR applies to organizations that collect data about EU residents, whether or not that organization has a physical presence in the EU. What’s more, violations can incur fines of twenty million euros or more. Thus, while non-EU news organizations may be less likely to come under immediate scrutiny because of the GDPR, they are still subject to its provisions and will benefit from thinking strategically about many of the issues it addresses. Moreover, the GDPR is likely to cause substantial changes in the operations of both digital platform and advertising companies, the effects of which will have undeniable consequences for publishers.

Key findings

- The GDPR applies to any organization that offers goods or services to EU residents and wishes to collect data about them. In particular, global publishers will be considered “data controllers” with regard to some of the personal data they collect through their websites, and therefore will be partly responsible for ensuring their lawful use. This includes publishers located outside the EU who target content toward EU residents and host digital ads that collect data about site visitors, etc.

- The GDPR definition of “personal data” is far broader than is typically understood in the United States. The GDPR considers any data that can be linked to a person—even if only in combination with other data—to be “personal data.” This greatly expands the types of data that require consent to collect.

- Consent must be obtained before any data is collected. Consent must also be specific and easily withdrawn. Web pages that load data-collecting ads before consent is obtained may violate the GDPR. Likewise, consent notices that employ legalese or require users to provide information unrelated to the services provided are invalid under the regulation. Finally, data subjects must be able to access, transfer, correct, or erase their data at any time, as well as withdraw consent for its continued use.

- Despite added complexities, media organizations with strong user trust may gain increased leverage with platform companies and ad networks once the GDPR is in place. Experts suggest that because these other players will have difficulty obtaining the consent they need from data subjects directly, publishers with strong user relationships will be able to do so more effectively and will therefore have more negotiating power in transactions with these companies.

Introduction

On May 25, 2018, one of this century’s most significant pieces of technology regulation will take effect. For all residents of the European Union (EU), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) will fundamentally transform the relationship between organizations that collect data and the people whom that data is about. While data regulations in the EU are hardly new—Europe has had digitally oriented legal frameworks for data in place since the mid-1990s—the GDPR differs substantially from its predecessors in the scope and immediacy of its impact. Specifically, this “generational” regulation is both immediately binding on all Member States, applies to data collected about EU residents by organizations located anywhere in the world, and carries significant financial penalties for non-compliance: fines of up to twenty million euros or four percent of the company’s annual global revenue.

While there is little doubt that global technology organizations—from software producers to service providers—will be the most impacted by the GDPR, because the new regulation applies to any organization that collects data about EU residents, media companies that target EU audiences will also be subject to the regulation. As many news organizations’ websites and apps may be the vehicle for collecting data about users—since they host, for example, third-party advertisements or even in-house analytics tools that place cookies on users’ devices—they will also be subject to GDPR requirements. Indeed, though the simple availability of a website in the EU is not sufficient for triggering GDPR applicability, any publisher that targets content to the EU may be subject to the regulation, whether or not they have an office or other physical presence in the region. Even for media organizations without an EU audience, the essential ways in which the GDPR will transform both social media and digital advertising will no doubt have strong reverberations throughout global publishing.

The purpose of this report, therefore, is twofold. First, it is meant to act as a primer and reference on the key provisions of the GDPR, with a focus on how they differ from previous EU regulation, and from prevailing U.S. customs and law. Second, through review of policy papers and interviews with industry experts, we offer an overview of the potential impacts of this regulation on technology platforms, digital advertisers, and publishers. We also cover how media companies around the world can begin to prepare for the challenges and opportunities this regulation will present.

Background: Privacy, Data Protection, and the GDPR

The GDPR is designed to bring consistency and uniformity to the governance of personal data in the EU. As adopted by the European Parliament, the GDPR enshrines and enforces Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union drafted in 2000, which “considers the privacy of communications and the protection of personal data to be fundamental human rights.”1 Although the Charter itself only became binding in 2009,2 general EU attitudes toward data privacy were first articulated in 1995 with the adoption of the Data Protection Directive, establishing the Article 29 Working Party (WP29, officially the Data Protection Working Party).3

While the Data Protection Directive outlined many key data rights for European citizens and created the “Data Protection Authorities” (DPAs) upon which the GDPR also relies for enforcement, unlike the GDPR, the actual implementation of the Directive was left up to Member States. Moreover, territorial applicability of the Data Privacy Directive was ambiguous:4 to be subject to the Directive, an organization had to use processing “equipment” located in the EU. This led both to uncertainty in enforcement and a series of legal disputes over whether this condition was met in the case of different digital “equipments”—for example, web cookies, JavaScript, ad banners, and spyware.

‘Adequacy’ Decisions and Safe Harbor

Where applicable, the Data Privacy Directive stipulated how information about EU citizens could be transferred to a country outside the EU, a circumstance only possible if the European Commission determined that the country in question offered an adequate level of personal data protection with “particular consideration given to the nature of the data, the purpose and duration of the proposed processing operations, the countries of origin, and final destination of the data, and that country’s laws, rules, and security measures.”5 These decisions are known as “adequacy decisions.”

While “adequacy decisions” were reached for a number of non-European countries in the years following the Data Privacy Directive adoption (including Andorra, Argentina, Canadian commercial organizations, the Faeroe Islands, Guernsey, Israel, the Isle of Man, Jersey, New Zealand, Switzerland, and Uruguay), the absence of “a single, overarching data privacy and protection framework”6 in the United States prevented it from receiving an adequacy decision under the Data Privacy Directive.

To ensure that the absence of an adequacy decision did not prevent the transfer of personal data between the EU and the United States, however, in 2000 both parties agreed on the “Safe Harbor Privacy Principles.” This agreement allowed U.S. companies to meet the “adequate level of protection” required by the Data Protection Directive by self-certifying annually to the U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC) that they adhered to certain data privacy requirements.7 The key principles of these requirements included: notice, choice, onward transfer, security, data integrity, access, and enforcement.i

Although participation in Safe Harbor was open to any U.S. organization subject to regulation by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) or the Department of Transportation (DOT)—for example, U.S. air carriers and ticket agents8—it was not the only mechanism through which American organizations could transfer EU data to the United States. Standard Contractual Clauses (SCC) approved by the European Commission and Binding Corporate Rules (BCR) were another option for multinational organizations. Moreover, the European data protection framework provides derogations under which data can always be transferred, such as: the performance of a contract, legal situations, and any time an organization has obtained the free and informed consent of the data subject. For example, this could include having the user accept the Terms of Service or privacy policy of a website or mobile app.

In principle, Safe Harbor required U.S. companies to self-regulate for privacy, while persistently failing to do so could potentially expose those companies to lawsuits in the United States and interrupt their EU-U.S. data flows. In fact, however, it would not be until an Austrian national, Maximillian Schrems, filed a lawsuit in Ireland in 2015 that Safe Harbor would come under review once again.

The U.S. Context

Although the U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment is often broadly construed as providing a “right to privacy,” the reality is that, unlike the EU, the United States “does not have a single, overarching data privacy and protection framework.”9 Instead, its data privacy laws are often described “as a ‘patchwork’ of federal and state statutes.”10 In particular, the U.S. framework rests largely on the concept of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), which is similar but not nearly as comprehensive as the EU concept of personal data.ii

The U.S. Privacy Act of 1974, for example, addresses how the federal government should manage the personally identifiable information it possesses (such as Social Security numbers), while the Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended government restrictions on telephone wiretapping to include computer transmission of electronic data. Yet for the most part, federal consumer privacy laws in the United States are almost exclusively industry-specific. For example, the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), along with its associated Privacy and Security Rules, places limits on who can access, share, and transfer many kinds of health data.11 In the education space, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) limits the ability of educational institutions to disclose information about a student’s educational record without the individual’s consent (or parental consent, if the student is under eighteen years old).12 Individual U.S. states may also have more general privacy protections in place. For example, Section 1 of the State Constitution of California names privacy as one of individuals’ “inalienable” rights.13 In general, however, data collected and shared in the course of regular business operations not governed by these specific regulations is not considered private and can be freely bought, sold, and exchanged.

In general, U.S. officials and industry representatives contend that the U.S. approach is nimbler than the one-size-fits-all EU approach; they also argue that the U.S. approach promotes and sustains technological innovations by enabling companies to use personal data in innovative ways, unhindered by cumbersome data protection regulations. Privacy-related U.S. advocacy groups in the United States, on the other hand, have long expressed concerns with the inconsistencies of the U.S. approach, and continue to urge Congress to enact comprehensive data protection legislation.14

Failure of Safe Harbor

On October 6, 2015, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) declared the Safe Harbor invalid. This decision stemmed from the complaint brought to the Irish DPA by Austrian Maximillian Schrems, concerning the transfer of his data from Facebook’s EU-based servers in Ireland to Facebook’s servers in the United States.15 Schrems argued that the United States “does not provide for an adequate level of data protection” since U.S. authorities may access personal data that is transferred over to Facebook’s U.S. servers.16 Initially, the Irish DPA dismissed the complaint, finding that it had no basis to evaluate the complaint since Facebook adhered to Safe Harbor.17 Schrems then took his claim to the Irish High Court, which referred the case to the CJEU.18

The CJEU’s October 2015 decision declaring Safe Harbor invalid was based principally on the finding that Safe Harbor has too many loopholes.19 For example, Safe Harbor may not apply if “national security, public interest or law enforcement requirements” are at stake, all relatively vague conditions which may be broadly interpreted. Moreover, U.S. public authorities such as local and national law enforcement agencies were not required to comply with Safe Harbor requirements.20 The CJEU concluded that the Safe Harbor scheme therefore “enables interference” by U.S. authorities, in part because it does not refer to U.S. rules or effective legal protections for data subjects, such as the option of judicial redress.21

Safe Harbor 2.0: EU-U.S. Privacy Shield

The CJEU’s ruling led to months of negotiations between the United States and the EU to replace Safe Harbor. On February 2, 2016, the European Commission and the U.S. Government reached a political agreement based on a new framework: the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield. The Commission adopted the framework on July 12, 2016, and it became operational shortly thereafter on August 1, 2016.22 At that time, the European Commission also committed to reviewing the Privacy Shield on an annual basis, to determine if it continued to ensure an adequate level of protection for personal data.23

The Privacy Shield framework is substantially longer and more detailed than the Safe Harbor, and was designed in large part to address the prior agreement’s perceived shortcomings. While the changes are far-reaching, they focus on addressing three main areas of concern, specifically, the handling of Europeans’ personal data by U.S. companies, the placement of limits and restrictions on U.S. Government access to and sharing of Europeans’ data, and the creation of judicial redress options for EU citizens who believe their data has been misused. In addition, companies participating in the Privacy Shield commit to abiding by the following seven Privacy Principles,iii which expand on the principles laid out in the Safe Harbor Agreement: notice requirements, limits on use, opt-out choices, security assurances, access rights, rights of recourse and liability, and accountability for onward transfer.iv

Umbrella Agreement, Judicial Redress, and the Trump Administration

Foundational to the Privacy Shield negotiations were two key agreements: the Umbrella Agreement and the Judicial Redress Act of 2015. The Umbrella Agreement24 protects the personal data of European citizens when it is exchanged between U.S. and EU law enforcement authorities, while the Judicial Redress Act extends protections under the U.S. Privacy Act of 1974v to citizens of “covered countries,” a list whose membership the U.S. Attorney General has the discretion to amend. On January 23, 2017, then-U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch extended this list to include all EU countries.25

The efficacy of both these agreements and the Privacy Shield in general, however, became the subject of uncertainty and concern just two days later when, on January 25, 2017, President Trump issued an Executive Order for “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States.”26 The Order requires, in part, that:

agencies shall, to the extent consistent with applicable law, ensure that their privacy policies exclude persons who are not United States citizens or lawful permanent residents from the protections of the Privacy Act of 1974 regarding personally identifiable information.27

This raised questions about whether the Order undermined privacy protections addressed by the Privacy Shield.

The U.S. Department of Justice has assured that this Order will not affect the privacy rights extended to EU citizens under the Umbrella Agreement, Judicial Redress Act, and Privacy Shield, though privacy advocates argue that this Order represents a “changed approach to privacy protections for non-U.S. citizens.”28

The 2017 Privacy Shield Review

The European Commission report of the first Privacy Shield review was published in October 2017. According to the report, the Privacy Shield continues to ensure an adequate level of protection for the personal data transferred from the EU to participating companies in the United States.29 The report confirms the United States has the necessary structures and procedures in place to ensure proper functioning of the Privacy Shield, including options for redress.30 It does, however, offer several recommendations to ensure the Privacy Shield’s continued success, including:

- “More proactive and regular monitoring of companies’ compliance with their Privacy Shield obligations by the U.S. Department of Commerce. The U.S. Department of Commerce should also conduct regular searches for companies making false claims about their participation in the Privacy Shield.”31

- “More awareness-raising for EU individuals about how to exercise their rights under the Privacy Shield, notably on how to lodge complaints.”32

- “Closer cooperation between privacy enforcers, i.e. the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Federal Trade Commission, and the EU Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), notably to develop guidance for companies and enforcers.”33

- “Enshrining the protection for non-Americans offered by Presidential Policy Directive 28 (PPD-28), as part of the ongoing debate in the U.S. on the reauthorization and reform of Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).”34

- “To appoint as soon as possible a permanent Privacy Shield Ombudsperson, as well as ensuring the empty posts are filled on the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board (PCLOB).”35

The WP29 also conducted a review of the Privacy Shield in November 2017,36 and outlined many of the same concerns, prioritizing the nomination of PCLOB members and of a Privacy Shield Ombudsperson, as well as legal protections for the privacy of EU citizens in U.S. law and demanding that they be “resolved” by May 25, 2018, when the GDPR enters into force. Thus, despite the relatively positive review of the Privacy Shield, concerns and uncertainty remain as the GDPR’s enforcement date approaches.

GDPR: Overview, Structure, and Governance

The first version of what would become the GDPR was released by the European Commission on January 25, 2012,37 as a proposal designed to put “individuals in control of their own data and reinforce legal and practical certainty for economic operators and public authorities.”38 The goal of the GDPR is to work toward a Digital Single Market by harmonizing and strengthening data privacy laws across Europe, thereby reshaping the way organizations across the region (and beyond) approach data privacy.39 Arguably, the most significant aspect of the GDPR is that it also applies to any company that handles the data of EU residents, wherever they are located:40

The GDPR will apply to the processing of personal data by controllers and processors in the EU, regardless of whether the processing takes place in the EU or not. The GDPR will also apply to the processing of personal data of data subjects in the EU by a controller or processor not established in the EU, where the activities relate to: offering goods and services to EU citizens (irrespective of whether payment is required) and the monitoring of behavior that takes place within the EU. Non-EU businesses processing the data of EU citizens will also have to appoint a representative in the EU.

Moreover, the fact that the GDPR is a regulation makes it immediately binding upon all Member States in its entirety. This stands in contrast to its predecessor, the Data Protection Directive, which had to be implemented separately by Member States. The GDPR will enter in force on May 25, 2018.41

Data Collection Model and Requirements

The GDPR does not, of course, simply prohibit the collection or use of individuals’ data by companies. While the general model for data collection under the GDPR can be broadly construed as “informed consent,” the GDPR spells out in substantial detail how (and when) consent must be obtained, and places important limits on how personal data can be stored and transferred. Likewise, the GDPR requires certain companies to appoint Data Protection Officers (DPOs), specific individuals who are responsible for ensuring and demonstrating compliance. In addition, it provides concrete avenues for individuals to file complaints about data misuse, and outlines the procedures by which such complaints will be evaluated and resolved.

Though the GDPR expands on many of the provisions of the Data Protection Directive, it also adds many new rules and concepts, including principles governing the processing of personal data, new rights for data subjects, more obligations for data controllers and processors, and provisions regarding redress.

Principles governing the processing of personal data

- Accountability: the GDPR provides that “the controller shall be responsible for, and be able to demonstrate compliance with [the principles related to processing of personal data]” (GDPR, 5).vi The designation of a Data Protection Officer, the conduct of audits, or the publication of Data Protection Impact Assessments for the most sensitive information all go toward this principle of accountability.

- Child protection: the GDPR includes the necessity to receive authorization from “the holder of parental responsibility over the child,” when the child is below sixteen years old—or thirteen years old in certain jurisdictions (GDPR, 8).

Rights of the data subject

- User interface: the information related to data processing should be “concise, transparent, intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language” (GDPR, 12).

- Right to erasure: the GDPR includes a right to “obtain from the controller the erasure of personal data concerning him or her without undue delay” (GDPR, 17).

- Data portability: the GDPR includes a right to “receive the personal data concerning him or her, which he or she has provided to a controller, in a structured, commonly used and machine-readable format and have the right to transmit those data to another controller without hindrance from the controller to which the personal data have been provided” (GDPR, 20).

- Automated decision-making opt-out: the GDPR includes a right “not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, which produces legal effects concerning him or her or similarly significantly affects him or her” (GDPR, 22).

Obligations for data controllers and processors

- Privacy by design: the GDPR provides that data protection should be protected by design (“implement appropriate technical and organizational measures, such as pseudonymisation, which are designed to implement data-protection principles, such as data minimisation, in an effective manner and to integrate the necessary safeguards into the processing”) and by default (“only personal data which are necessary for each specific purpose of the processing are processed. (. . .) In particular, such measures shall ensure that by default personal data are not made accessible without the individual’s intervention to an indefinite number of natural persons” (GDPR, 25).

- Data breach notification: the GDPR provides that “the controller shall without undue delay and, where feasible, not later than 72 hours after having become aware of it, notify the personal data breach to the supervisory authority. (. . .) Where the notification to the supervisory authority is not made within 72 hours, it shall be accompanied by reasons for the delay” (GDPR, 33).

Provisions for redress

- Compensation and liability: the GDPR gives “any person who has suffered material or non-material damage as a result of an infringement of this Regulation (. . .) the right to receive compensation from the controller or processor for the damage suffered,” under the following conditions:

- “Any controller involved in processing shall be liable for the damage caused by processing which infringes this Regulation.”

- “A processor shall be liable for the damage caused by processing only where it has not complied with obligations of this Regulation specifically directed to processors or where it has acted outside or contrary to lawful instructions of the controller” (GDPR, 82).

Changes in Enforcement Mechanisms

As with the Data Protection Directive, the key actors for the enforcement of the GDPR are the national Data Protection Authorities (DPAs), which have significantly more power than they did previously. For example, under the GDPR, DPAs can levy fines of up to twenty million euros or four percent of annual global turnover, whichever is higher. Previously, national DPAs like the French CNIL were only able to levy a maximum fine of 300,000 euros.

Classes of administrative fines

The GDPR also creates two categories of administrative fines. Depending on “the nature, gravity and duration” of the infringement, its “intentional or negligent character,” any “action taken by the controller or processor to mitigate the damage suffered,” as well as the “degree of cooperation with the supervisory authority,” and whether notification was done properly, the GDPR outlines two tiers of penalty:

- The first tier can be subject to fines up to “10 000 000 EUR, or (. . .) up to two percent of the total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.” This category includes infringements of the following provisions by the controller and the processor:

- Child’s consent

- Data protection by design and by default

- The responsibilities of the Data Protection Officer

- The obligations of organizations related to certification schemes

- The second tier can be subject to fines up to “20 000 000 EUR, or (. . .) up to four percent of the total worldwide annual turnover of the preceding financial year, whichever is higher.” This category includes infringements of the following provisions by the controller and the processor:

- The basic principles for lawful processing of personal data, including conditions for consent and the provisions for special categories of personal data

- The rights of the data subject, as defined in the Regulation

- The obligations in the case of an international transfer of personal data

- In the case of non-compliance with an order by a DPA to suspend processings of personal data or data flows, as well as a failure to provide access to all information required by the DPAs, including access to the premises and equipments

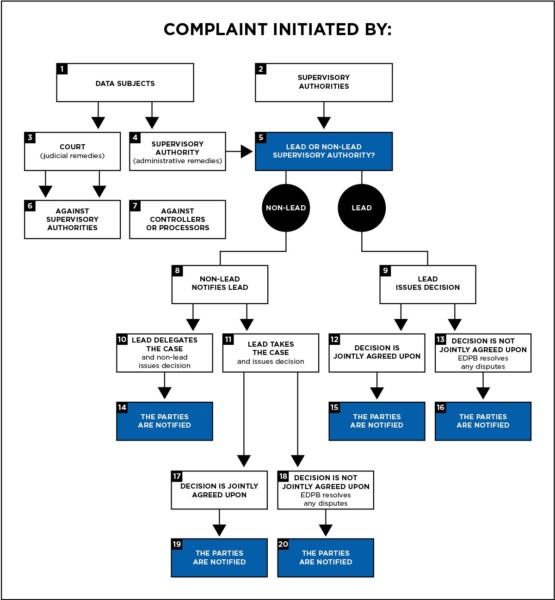

The GDPR also creates a “lead supervisory authority” for every organization established in the EU, which corresponds to the country where the organization has its main establishment (in most cases, its headquarters).vii While data subjects will be able to file complaints in their own Member State (as well as States where they work or suspect the infringement occurred), the lead supervisory authority of the company will always have the option of ruling, or delegating to the non-lead authority where the complaint was filed. This gives companies a “one-stop shop” for data protection issues, while giving the citizens the option to file their complaints in their home country. DPAs will also be able to pursue infringement actions on their own accord. Organizations subject to the GDPR that do not, however, have an EU establishment will be required to deal with the supervisory authority of any member state in which a complaint is filed. A full map of the complaint process follows.42

Figure 1: An overview of the GDPR complaint process. Source: https://iapp.org/resources/gdpr-tool/

The GDPR’s Impact on the Media Industry

No one in the news business needs to be told that nearly everything about the process of producing, distributing, and funding journalism has changed dramatically over the past twenty years. Yet arguably one of the most challenging aspects of the digital transformation has been its impact on the advertising ecosystem, and on publishers’ roles within it.

In a print-dominated journalism landscape, publishers were a requisite intermediary in the two-sided market between advertisers and consumers: publishers gathered readership and advertisers paid to reach these audiences. In addition to providing a channel for advertising, however, in a print-based world publishers had an effective monopoly on the data about their readers, as well as on the access to them. Through subscription data and direct surveys, publishers collected and controlled the vast majority of reader data, which, combined with the relatively limited amount of available ad “real estate” available in print publications, created a premium market for advertising alongside traditional journalism. The rise of the web, of course, broke these models in multiple ways.

As speciality sites rose to prominence (Craigslist being an oft-cited example), they siphoned off standing streams of revenue that had demanded little investment or ongoing development from publishers. In mid-2003, the constraints on available ad space were shattered by the launch of both WordPress and Google’s AdSense43—the former making organized, visually appealing web publishing accessible to non-programmers at little or no cost, and the latter allowing even small websites to place contextual advertising alongside their content.viii For the first time, advertisers were able to reach audiences without going through media publishers.

Moreover, with the 2005 launch of Google Analytics44 and its subsequent purchase of DoubleClick in 2008,45 publishers’ control over audience data also began to erode. This process was accelerated by the launch of Facebook Marketplace (2009) and even by organizations like BuzzFeed, which in 2010 made its “viral dashboard” available to other publishers (including partners like Time, Fox News, and Huffington Post46) in exchange for their organizations’ audience data. With these, the intermediary function that publishers played as data brokers between advertisers and audiences was lost. As the CEO of one online data-brokerage site told Julia Angwin at The Wall Street Journal in 2010, “Advertisers want to buy access to people, not Web pages.”47

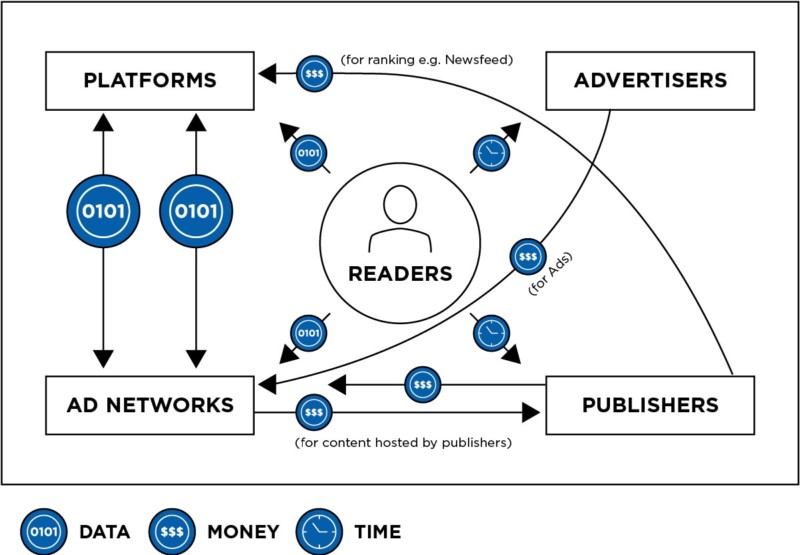

Today, it is difficult for publishers to compete with advertising networks on the market for online advertising because they control only a fraction of both the advertising space and their audience data. The result is that there are essentially four players in the internet data and advertising ecosystem:

- Platforms (such as Google and Facebook), which collect both original data provided directly by consumers (in the form of shares, web searches, and the like) in addition to operating advertising networks

- Ad networks, which typically collect incidental data (e.g., web-browsing activity) and place ads

- Advertisers, which collect little data and rely on both ad networks and platforms to conduct data-collection and targeting on their behalf

- Publishers, which create and host content where ads are servedix

An overview of the resource flows among key players in the online economy.

While arguments about platform versus publisher designations surely abound,48 49 50 the GDPR defines actors’ responsibilities under the regulation not by these categories, but by their role in handling personal data: either as “controllers” or as “processors.” In short, data controllers (of which there may be more than one) determine why data is being collected, while data processors are only in charge of the processing. Crucially for media organizations, data controllers are in charge of ensuring that data processors abide by the consent of users throughout the data life-cycle. This is a new responsibility that publishers will have to adopt: they will be in charge of ensuring that every organization processing data collected on their website does so for purposes compatible with the purposes for which it was collected.

Who is a ‘controller’? Who is a ‘processor’?

According to the GDPR a “controller” is:

the natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which, alone or jointly with others, determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data (GDPR, 4 [7]).

By contrast, a “processor” is:

a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller (GDPR, 4 [8]).

Given the above definitions, of course, whether a particular organization is a controller or a processor in a given situation is not always obvious—and in certain situations a single organization may be a controller, a processor, or both, depending on the particular data collected and how it is used. For example:

Case 1: Direct marketing/in-house ads

If a news organization collects personal information from subscribers that is then processed by the marketing team for sales purposes, the news organization would be both controller (i.e., the party deciding what gets collected and how it is used) and the processor (because it is also doing the analysis in-house).

Case 2: Publishers contract third-party services

For example, if a news organization uses third-party services such as MailChimp to manage and send a newsletter, MailChimp would be a processor, since its services involve hosting, accessing, and querying data that the news organization (the controller) has decided to collect and use.

Case 3: Publishers sell ad space on their websites

In many cases, news organizations host third-party content (such as digital advertisements) that collects data about visitors. Although in some ways it is the ad network that “determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data,” in this circumstance the news organization is at least one controller of the data because it technically has the option of not providing any data to the ad network, though clearly at the cost of ad revenue. In most of these cases, however, the ad network itself is also both a controller and a processor. As a result, news organizations and digital ad networks may often be joint controllers (GDPR, 26).

In almost every circumstance, then, news organizations are at least data controllers, if not also data processors. What this means is that news organizations that target content or services to EU residents will need to plan carefully how they collect, handle, and share any information about their readers. Given news organizations’ direct relationships with their readers, we posit that well-prepared news organizations may actually benefit from the GDPR, especially relative to other actors in the space.

Impact on Platforms, News Organizations, and Ad Networks

Arguably, the GDPR will have the largest impact on platforms, for whom the rules requiring that consent be freely given “by a clear affirmative act” (GDPR, 32) and limits on “further processing” of data may reduce their ability to accumulate long-term profiles about individuals, as well as use what data they do have for ancillary purposes.

This is particularly likely given the very specific way in which the GDPR determines whether consent is, in fact, freely given. Specifically, the regulation states that consent is not “freely given” if “the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment” (GDPR, 42). Similarly, the regulation does not view consent as “freely given” if “the provision of a service . . . is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract” (GDPR, 7 [4]). Thus, any “free” app or service that is, in fact, monetized through the use or resale of personal data (especially unrelated to the specific service being provided) will only be successful to the extent that it can persuade users to actively consent to such uses.x

Further complicating the landscape for large platforms in particular are the logistical challenges posed by the GDPR’s “right to access” provisions, which give data subjects far-reaching rights around the personal data held about them by companies. For example, the GDPR specifies that data subjects have the right to an electronic method for requesting, free of charge, “access to and rectification or erasure of personal data” (GDPR, 59). The regulation then goes on to specify that these requests should be fulfilled “without undue delay,” but more specifically, “within one month” (GDPR, 59).

These provisions may raise particular challenges for companies that aggregate data for the purposes of analysis, during which a direct connection between the data subject and the data itself may, under current systems, no longer be explicitly maintained. In fact, such processes help comply with the GDPR’s mandate for “privacy by design” (GDPR, 78; GDPR, 25).

Yet removing explicit identifiers (such as name, address, handle, or user ID, etc.) may also not be enough to ensure that aggregated data is no longer considered “personal data” under the GDPR, which treats as personal data “any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person” (GDPR, 4). As both substantial reporting and academic research have shown, truly de-identifying data is not a simple task. For example, in 2000, Harvard professor Latanya Sweeney demonstrated that eighty-seven percent of the U.S. population could be uniquely identified using a combination of their gender, birth date, and five-digit zip code; in 2006, researchers Arvind Narayanan and Vitaly Shmatikov demonstrated that the “Netflix prize” dataset could be used to identify individual users, despite the removal of identifying information.51 52 53 In the decade since, thanks in part to the volume and prevalence of online information, the ability to re-identify individuals using data that has no explicit identifiers has only grown, and has been frequently highlighted in the press using data sets like taxi rides54 55 56 and online browsing histories,57 among others.xi

This raises the question of whether the GDPR’s right to erasure and correction will require companies to maintain these links in some form or simply discard data more promptly. Either way, these regulations imply serious technical and business-practice overhauls that are likely to be felt more acutely by companies whose business models are built on large-scale data collection and analysis.

News organizations

Although news organizations do collect and process personal data, the majority of GDPR-relevant personal data collection by news organizations is done via their websites or apps for advertising purposes—and this data is often not retained by the news organization itself. However, since, as we explained, news organization are at minimum a “joint controller” of such data, they will be responsible both for obtaining consent from data subjects and for ensuring that the data handling processes of any vendors with whom they contract (e.g., online advertising networks) are compliant with the regulation. To the extent that news organizations do collect and store such information for internal purposes, of course, they will be responsible for its proper processing as well.

On the one hand, these requirements suggest significant new burdens for news organizations that may not currently have well-defined processes or oversight for the handling of such data. For example, many news organizations may not even have a comprehensive inventory of all of the companies that are collecting personal data on their websites and what those companies are doing with that data. As one editor from Le Monde told us: “On any page, you’ll find between five and fifteen ad trackers and you try to find out . . . what they’re collecting and what they’re doing with the data . . . And some of them just don’t say.”

Indeed, recent research indicates that perhaps most website owners do—and potentially cannot—effectively audit the trackers and other materials that are loaded on their sites. A recent post from Princeton researcher Arvind Narayanan and his colleagues detailed which websites may potentially host “session replay scripts,”58 which record user interactions on websites as if they were “looking over your shoulder.” Among the sites that may load such services are realclearpolitics.com, cbsnews.com, and others. In addition to being able to capture data like passwords and other personal information,59 these scripts often cannot be effectively detected by site owners.60 Under the GDPR, news organizations will be responsible for ensuring that any third-party scripts or advertisements loaded by their pages comply with the regulation’s requirements, or risk liability for the mishandling of audience data, essentially putting a due diligence requirement on website owners to “clean their websites” and make sure that no third parties are tracking users, with or without the owners’ knowledge.

One particular topic of concern is that the GDPR requires that consent be obtained from site visitors before any data is collected about them. If enforced strictly, news organizations may have to rethink the timing and placement of advertisements and other scripts on some of the most valuable ad real estate they have: the homepage. In conversations with the CNIL (the French DPA), for example, Le Monde editors said they were struggling to devise a plan for their homepage that would satisfy the regulation without cutting homepage traffic and ad revenue off at the knees. While many European sites currently use small pop-up notices to inform readers that a site uses cookies (as part of their compliance with the Data Privacy Directive), the CNIL has indicated that this may not qualify as genuine “consent” under the GDPR, since some ads may be loaded (and data collected) before the required consent click has taken place. As a result, a more radical solution, such as a “roadblock” consent agreement or “splash page” for new users, might be required. However, as a Le Monde editor described it:

Basically, [a splash page is] what CNIL would like all of us to do because in their—in their opinion, [it’s] the only way to make sure that the proper consent is given. And, of course, no French editor wants to do this because you know that if you do that you’ll have fifteen or maybe twenty percent of your traffic that will disappear.

Moreover, it’s unclear as yet whether consent to data-collection can be made the “price of access” to a site; while the European IAB has interpreted the GDPR as allowing this,61 other organizations disagree.62 Regardless, publishers who are already reluctant to put up paywalls may be understandably hesitant to demand that users consent to tracking instead. Either way, the risk to homepage ad revenue could be serious, especially given the importance of those ads to publishers’ revenue streams. As a Le Monde editor put it: “[Homepage ads are] the ones you sell at the highest price. You can’t cut them unless you’re willing to take [something like a] forty percent drop in your ad revenue.”

Yet as tricky as GDPR compliance will be, compared to other businesses news organizations may, on balance, actually gain from the new regulation. Because all organizations will need to obtain consent in order to collect data, the direct and trusted relationship with consumers that news organizations have (or can repair) may help them obtain this consent more readily, giving them a valuable edge over ad networks that lack name recognition, or even large platforms about whom users may be conflicted.

Chris Pedigo, a senior vice president for Digital Content Next—a trade organization for digital content companies including the Associated Press, Bloomberg, the Financial Times, Hearst, and The Washington Post—believes that media companies will be in a favorable position, especially as compared to their platform and ad network counterparts:

Think about, you know, a publisher like The New York Times. They tend to want to know more about their audience so that they can see how they use the site, so they can recommend other articles that they might be interested in, remember a customer when they come back . . . [but] that’s the sort of extent of it . . . But even if you had to go to a customer and say, you know, “Hey, we would like consent to track you while you’re on our site so we can recommend other articles for you, so that we can remember you when you come back to visit us,” most—most people are going to say that’s fine. They get that relationship with The New York Times.

By contrast, said Pedigo, platform companies like Google and Facebook will have a harder time getting consumers’ consent under the GDPR because “they’ll have to list out all the reasons that they want to track the consumer.” Many of these reasons may include the types of activities that consumers feel are simply an invasion of privacy,63 making them less likely to agree. Moreover, given the limited revenue that publishers actually garner from these platforms,64 publishers may choose to hold on to the audience data they do collect, and attempt to strike more favorable terms than they currently provide.

An editor at The Guardian shared a similar view, saying, “I think some publishers are more positive than others about the impact that the GDPR will have because, in theory, you just have more trust in news brand websites than . . . any other websites.”

Advertisers

Perhaps the sector that will face the most challenges under the GDPR will be the third-party ad networks that are not already part of one of the large platform companies (e.g., Google, Facebook). As of 2017, Google and Facebook claim seventy-seven cents of every dollar spent on digital advertising in the United States, with no other single company claiming even as much as three percent of the total market share.65 While the GDPR may hinder some of these companies’ data collection and/or sharing activities, the regulation may well squeeze smaller advertising networks even more, potentially magnifying the dominance of this duopoly in online advertising. These smaller ad networks, for example, typically lack the direct consumer relationships needed to secure consent from users on their own behalf, but may also find that media publishers and other website hosts are reluctant to ask for user consent for the broad range and volume of data that these advertisers can presently access without hindrance. Without access to the data on which they currently rely, smaller advertising networks may be simply cut out of the online market altogether unless they can find a way to gain some advantage over the platforms in compliance, user-friendliness, or rates. In this environment, platform companies and website hosts—such as media companies—that have a brand-name relationship to their users are likely to have more success in persuading individuals to give up their information, and therefore may have increased power in the advertising market under the GDPR.

Other Concerns for News Organizations

While the impact of the GDPR on both business processes and revenue streams is understandably the focus for many companies, the impact for news organizations which rely on information gathered about people to do their work may have other ramifications.

Journalistic data gathering and retention

While the GDPR does explicitly note that exemptions should be made for data processed “solely for journalistic purposes,” and that it is essential to interpret artistic, academic, and journalistic activities “broadly” (GDPR, 153), some journalists are still concerned about the impact that data subjects’ right to erasure, for example, may pose to newsgathering. As one Guardian editor put it: “I think from a journalism perspective, if you had to get rid of data that you processed after a certain amount of time, you [might] lose . . . long-term investigations.”

Although the GDPR does provide a “public interest exception” when it comes to the removal and erasure of information, it explicitly stipulates this only in the case of official documents.xii Instead, the GDPR specifies exemptions on any data processing required “for exercising the right of freedom of expression and information” (GDPR, 17 [3]), but these are left up to the Member States to define and implement (GDPR, 153). Thus, there is the possibility for uneven interpretations of these exemptions from country to country.

The ‘Right to Be Forgotten’

When the “Right to be Forgotten” (RTBF) was established in Europe in March 2014, many in the news industry feared that the result would have a chilling effect on both news gathering and publishing.66 Yet in the three years since it was enacted, research suggests that the impact of the Right to Be Forgotten on access to news information has, in fact, been minimal.67 Though the GDPR unsurprisingly enshrines this right, it also modifies the methods of redress in ways that some experts fear may ultimately be problematic for freedom of expression.

In the landmark RTBF case, Google Spain v. AEPD and Mario Costeja González, the courts rejected the idea that the news publisher should be forced to take down content.68 Google was, however, ultimately forced to remove links to the specified material in some of its search results. With the increased penalties imposed by the GDPR for failing to delist content in a timely way, some scholars fear that digital intermediaries (such as social media sites) will be too quick to comply with removal requests once the GDPR is in effect, which may chill online speech by placing liability concerns—and stiff financial repercussions—ahead of the freedom of information and expression rights of other parties that might be affected.

As Daphne Keller, director of Intermediary Liability at the Stanford Center for Internet and Society, explains in her recent paper, “The Right Tools: Europe’s Intermediary Liability Laws and the 2016 General Data Protection Regulation”: “Even Data Protection experts can’t say for sure how the GDPR answers hugely consequential questions, like whether hosting platforms must carry out RTBF removals.”69

Keller also points out that different interpretations exist as to whether hosts like Facebook or Twitter are, indeed, engaging in the kind of data indexing and “profiling” described in the Google Spain case, which was the foundation of the order requiring Google to delist content. As Keller notes, however:

Another possible interpretation is that hosts trigger RTBF obligations when they let users search hosted content for names, generating a search result “profile” based on content stored on the host’s servers. If that were correct, and if Twitter were a Controller, it would not have to delete my tweet about Matilda Humperdink—but it might have to delist it from results in the Twitter’s search box.

Keller thus highlights an important issue that may arise: the path of least resistance for content hosts would be to avoid both fines and additional scrutiny by removing reported material “inconspicuously, without acknowledging any Controller status or legal obligation, [and] by classing the removal as voluntary.” An obvious potential consequence of this is that even valid content may be hidden from view, even in cases where the complaints themselves are substantially invalid.

However, while delisting does make it harder to access this content, the WP29 guidelines on the implementation of this RTBF clearly state that “the original information will still be accessible using other search terms [that the data subject’s name], or by direct access to the publisher’s original source,”70 which reduces the impact of systematic removal by content hosts.

Keller also addresses a second potential issue: a threat to freedom of expression. She argues that relying on the existing Intermediary Liability laws under the eCommerce Directive for notice-and-takedown and absolving content hosts of any Right to be Forgotten obligations would be effective in mitigating the risks that the GDPR currently poses to freedom of expression.xiii While the RTBF clearly has not had the impact on freedom of expression that some of its opponents thought it would, it is currently unclear how some GDPR provisions will be interpreted and enforced.

In this respect, despite its nature as a Regulation and not a Directive, the GDPR relies on DPAs for enforcement. While the network of DPAs has been preparing to cooperate and coordinate post-May 25, 2018, logistical challenges still remain. The road to EU-wide consistent enforcement of the GDPR is uncertain.

Preparing for Enforcement

Who is affected?

As noted throughout this report, the GDPR applies to all organizations offering “goods and services” to individuals in Europe, regardless of whether or not the service requires payment (GDPR, 23), or whether the organization has a physical presence in the EU. At the same time, the fact that a website or service is available to EU residents is insufficient to trigger governance by the GDPR:

The mere accessibility of the controller’s, processor’s or an intermediary’s website in the Union, of an email address or of other contact details, or the use of a language generally used in the third country where the controller is established, is insufficient to ascertain [applicability]; factors such as the use of a language or a currency generally used in one or more Member States with the possibility of ordering goods and services in that other language, or the mentioning of customers or users who are in the Union, may make it apparent that the controller envisages offering goods or services to data subjects in the Union (GDPR, 23).

In other words, virtually any media organization with content directed toward European audiences might be considered liable for enforcement under the GDPR, especially if subscriptions are offered within the EU (whether or not a subscription requires payment, or is mandatory for access to all content).

Who can complain?

As illustrated in Figure 1, there are actually multiple parties that can file a complaint under the GDPR. In addition to an individual whose data is being collected (the “data subject”), supervisory authorities can initiate complaints as well. Moreover, the GDPR does allow for a kind of “class action” suit, in which a data subject may:

mandate a not-for-profit body, organisation or association . . . to lodge a complaint on his or her behalf with a supervisory authority, [and] exercise the right to a judicial remedy on behalf of data subjects or, if provided for in Member State law, exercise the right to receive compensation on behalf of data subjects (GDPR, 142).

Obtaining Consent

While the GDPR does not specify particular mechanisms for obtaining consent, the regulation stipulates that consent must be obtained before any data is collected. As previously noted, in practical terms this may mean requiring a splash page for organizations that have ads on the homepage, or delaying the display of ads until consent has been obtained. While it is not yet clear whether such extreme measures will be required, it is worth noting that the notion of consent under the GDPR is far broader and more nuanced than U.S. organizations might expect.

For example, the regulation requires that:

Consent should be given by a clear affirmative act establishing a freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous indication of the data subject’s agreement to the processing of personal data relating to him or her (GDPR, 32)

While this may seem straightforward enough, the regulation is extremely particular about what constitutes “freely given” consent. For example:

Consent should not be regarded as freely given if the data subject has no genuine or free choice or is unable to refuse or withdraw consent without detriment (GDPR, 42).

Finally, it states:

When assessing whether consent is freely given, utmost account shall be taken of whether, inter alia, the performance of a contract, including the provision of a service, is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the performance of that contract (GDPR, 7 [4]).

In other words, the GDPR puts significant limits on the ability of companies to collect data from users that is not directly related to the provision of the service being offered—a regular practice of many apps.71 72 73 74

The regulation also describes the manner in which consent must be obtained. Given that most people do not read privacy policies75 (perhaps because they do not have time76), the regulation stipulates that:

The request for consent shall be presented in a manner which is clearly distinguishable from the other matters, in an intelligible and easily accessible form, using clear and plain language. Any part of such a declaration which constitutes an infringement of this Regulation shall not be binding (GDPR, 7 [2]).

In other words, requests for consent cannot be obfuscated within “long illegible terms and conditions full of legalese.”77

Withdrawing consent

Embedded within the consent provisions of the GDPR is the requirement that just as companies must obtain consent to collect data, they must provide an equally easy method for withdrawing consent:

The data subject shall have the right to withdraw his or her consent at any time . . . It shall be as easy to withdraw consent as to give it (GDPR, 7 [3]).

Yet while withdrawal of consent does not “affect the lawfulness of processing based on consent before its withdrawal” (GDPR, 7 [3]):

a data subject should have the right to have his or her personal data erased and no longer processed where . . . a data subject has withdrawn his or her consent (GDPR, 65).

From a data management perspective, this requirement presents a fundamental departure from prior practice, especially in the United States. For example, when the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) revised the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule (COPPA) in 2012, it explicitly exempted from the (then) newly introduced parental consent requirements any data (including images or videos of children, or audio of their voices) collected before the rule went into effect on July 1, 2013.78 Under the GDPR, once a user has withdrawn consent, no further processing of their data may take place, even if collected prior to the withdrawal, which might force companies to audit their data centers for such data.

The potential technical challenges to complying with the consent withdrawal process, moreover, are significant. As previously discussed, the association between a given piece of data and the person to whom it pertains may not be maintained in many existing data storage systems, and relying on the removal of explicit identifiers to maintain privacy may be materially insufficient under the GDPR. Given that the GDPR considers personal data to be any data which “could be attributed to a natural person [including] by the use of additional information” (GDPR, 26), the impact on technical systems that are not designed to easily identify and erase the data of a particular individual could be significant.

This is even truer for larger systems, where backup copies of data may be kept in multiple locations (including “cold” backups in offsite warehouses) in order to protect against power loss, data corruption, or simply to improve system performance. For the managers of such systems, the imperative to both withdraw consent and allow “erasure” (discussed in the next section) has far-reaching business implications.

Handling Breaches, Access, Erasure, and Portability

In addition to the broad scope of the organizations and data types that are governed by the GDPR, the regulation provides detailed stipulations about how data must be handled once it has been collected.

Breaches

According to the GDPR, a personal data breach constitutes:

a breach of security leading to the accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to, personal data transmitted, stored or otherwise processed (GDPR, 4 [12]).

Given the relatively broad definition of personal data under the GDPR, these breach notification requirements apply to a much greater volume of incidents than in the United States. For example, though breach notification laws vary from state to state, they often apply only to data that contains some kind of account or ID number, such as driver’s license, credit card, debit card or social security number, or data that permits access to accounts (such as passwords and security questions).79

The GDPR also places much more stringent time requirements on notifying both authorities and consumers about personal data breaches. In any case where a breach is deemed to pose “a risk for the rights and freedoms of individuals,”80 the notification must be made within seventy-two hours of its discovery, unless “early disclosure could unnecessarily hamper the investigation of the circumstances of a personal data breach” (GDPR, 88). By contrast, only a handful of U.S. states even specify a time frame, with those that do allowing from thirty to ninety days.81 To cite a recent example, Uber’s disclosure of a data breach more than a year after it took place would almost certainly be a violation of the GDPR and would leave the company open to hefty fines.82

Right to access, data portability, and transfer

In line with the right to withdraw consent, the GDPR also stipulates that data subjects be given the right to access and, where applicable, correct any data held about them:

Modalities should be provided . . . to request and, if applicable, obtain, free of charge, in particular, access to and rectification or erasure of personal data and the exercise of the right to object (GDPR, 59).

Moreover, an electronic means for making these requests must be provided, and:

The controller should be obliged to respond to requests from the data subject without undue delay and at the latest within one month (GDPR, 59).

In addition to being able to access and correct their data via electronic means, under the GDPR data subjects must also be able to retrieve any data that is processed via “automated means” in a “structured, commonly used, machine-readable and interoperable format” (GDPR, 68). Moreover:

The data subject shall . . . have the right to transmit those data to another controller without hindrance from the [original] controller . . . the data subject shall have the right to have the personal data transmitted directly from one controller to another, where technically feasible (GDPR, 20 [1–2]).

To support this, the GDPR encourages the development of such “interoperable formats,” but little guidance is offered as to how this should be approached.

Right of erasure/Right to Be Forgotten

The GDPR also uses “Right to Be Forgotten” language to describe its erasure stance, which requires that individuals be given:

the right to erasure should also be extended in such a way that a controller who has made the personal data public should be obliged to inform the controllers which are processing such personal data to erase any links to, or copies or replications of those personal data (GDPR, 66).

Importantly, this “informing” of other controllers may also explicitly include “technical measures” (GDPR, 17 [2]), such as automated notification or, presumably, programmatic flags or notices.

Demonstrating Compliance

There is, of course, no one-size-fits-all solution to GDPR compliance. It would be unrealistic to suggest that compliance requires less than a comprehensive examination of an organization’s data collection, handling, storage, and retention practices. For organizations whose data-analysis activities are large-scale and central to their business (read: platforms companies, though media companies that do significant data analysis and cross-targeting might potentially qualify), the GDPR requires the appointment of a Data Protection Officer (DPO) who must be provided with sufficient access, independence, and resources to monitor and ensure compliance with the GDPR within the company.xiv Crucially, in its accountability provision, the GDPR stipulates that controllers need to be “demonstrably compliant” with the law (GDPR 5 [2]).

For other organizations, sufficient guidance should be available via the Data Protection Board, whose composition, authority, and duties are also laid out in the GDPR.xv

Compliance, then, is essentially a matter of identifying the risks to personal data within an organization and the best practices for mitigating those risks, followed by the implementation “of approved codes of conduct, approved certifications, guidelines provided by the Board or indications provided by the Data Protection Officer” (GDPR, 77). Exactly what those codes of conduct, certifications, and other guidelines will be remains to be seen, but organizations would do well to stay aware of the Data Protection Board’s proceedings on these topics.

Privacy by design

While the current dearth of approved policies and codes of conduct may seem daunting, documentation of efforts to meet the above-mentioned requirements with respect to consent and data rights will no doubt play a role in any evaluation of potential violations, especially in the early days of the regulation’s enforcement. To support this, the GDPR advocates a general approach of “privacy by design”—a methodology which stipulates that privacy considerations be represented at every stage of design and engineering processes. In the language of the GDPR:

Such measures could consist, inter alia, of minimising the processing of personal data, pseudonymising personal data as soon as possible, transparency with regard to the functions and processing of personal data, enabling the data subject to monitor the data processing, enabling the controller to create and improve security features (GDPR, 78).

Data minimization, moreover, might include:

technical and organisational measures for ensuring that, by default, only personal data which are necessary for each specific purpose of the processing are processed . . . In particular, such measures shall ensure that by default personal data are not made accessible without the individual’s intervention to an indefinite number of natural persons (GDPR, 25 [2]).

Certification bodies

The Data Protection Board may designate certification bodies that are authorized to certify specific processes and practices, and may also:

adopt implementing acts laying down technical standards for certification mechanisms and data protection seals and marks, and mechanisms to promote and recognise those certification mechanisms, seals and marks (GDPR, 43 [9]).

The criteria for accrediting such certification bodies will be made public and transparent (GDPR, 43 [6]) by the Data Protection Board.

Deploying New Technologies

Like most regulations, the specifics of the GDPR are designed to address the data privacy and control issues presented by current technologies. However, just as data collected before the adoption of the GDPR is not exempt from its rules (such as the right of erasure or withdrawal of consent), the regulation stipulates that the impact of new technologies on data rights be evaluated before they are deployed. Specifically:

Where a type of processing in particular using new technologies . . . is likely to result in a high risk to the rights and freedoms of natural persons, the controller shall, prior to the processing, carry out an assessment of the impact of the envisaged processing operations on the protection of personal data (GDPR, 35 [1]).

Though at first glance this may seem like a straightforward requirement, the reality is that evaluating the privacy implications of a new process is far from a simple proposition, and identifying privacy-preserving ways to perform tasks like large-scale computation and data analysis remains an area of active computer-science research.83 84) While GDPR compliance may realistically slow the deployment of new data-analysis technologies, it may simultaneously spur more active research and development in the areas of privacy- and security-related technology.

Conclusion

There is no doubt that GDPR compliance will have a radical impact on the operations and business practices of any organization that deals with data about people, which in today’s web-driven environment means virtually every organization imaginable. While news organizations and media companies whose work makes them subject to the GDPR will certainly have some changes to make, the most substantial impact will be felt by technology platforms and advertising companies, whose cross-purpose data use and complex user relationships will likely complicate the process of obtaining consent for the types of business practices upon which some of their revenue streams currently depend.

Of course, any fallout for platforms and advertisers will necessarily have an impact on media companies, many of whom rely on the reach and revenue that these industries provide in order to disseminate and support their work. Yet on balance, the regulation may ultimately strengthen the position of news organizations that have strong relationships with their audiences, and may even partially restore news organizations’ role as intermediaries for reader data. This would then allow news organizations to more selectively (and profitably) share this data with advertisers and/or platforms companies. Thus, while the direct impact of the GDPR on news gathering is likely to be minimal, media organizations with European audiences would do well to not only prepare themselves to be compliant with the regulation, but to avoid business decisions that may be profitable in the short term at the cost of reader trust, clearly a reinforced asset post-GDPR.

For media companies without a substantial EU audience, of course, the implications of the GDPR are less clear. Yet while non-EU-facing news organizations will not have to immediately concern themselves with GDPR compliance in their own practices, it is unlikely that they will be fully shielded from the effects of the regulation, especially as it necessarily transforms the practices of platforms and advertisers. In the short term, for example, non-EU markets may see an increased share of online advertising dollars, as the complexity of the regulation and concerns about compliance and liability temporarily make less-regulated markets more attractive for both ad networks and advertisers. As the markets in Europe normalize, however, news organizations in other regions may experience a set of longer-term secondary effects.

For example, unless GDPR enforcement produces dramatically negative economic effects (as was predicted around the Right to Be Forgotten,85 but has not clearly materialized as argued), it is possible that similar regulations may be imposed in other regions; Brazil, for one, may be headed in this direction,86 and in September 2017 the UK introduced legislation designed to substantially mirror the protections of the GDPR87 in advance of Brexit. Given Americans’ increasingly negative attitudes toward third-party informations sharing (see Pew’s recent work on “Privacy and Information Sharing,”88) and even some indications from Congress that companies should be held liable for information collected about consumers,89 it is not unthinkable that increased data regulation will come to U.S. markets in the next several years.

More immediately, companies subject to the GDPR must decide whether they will achieve compliance by building separate, parallel systems and processes for use in European markets, or whether they will simply convert all of their business processes to conform to the regulation. Especially for large, multinational corporations (such as platform and technology companies) the cost of lost interoperability and maintaining parallel systems may make a fully compliant approach more cost-effective in the long run. The result is that their global practices may change substantially, in ways that all organizations dependent on their services (as so many news organizations are) will likely feel.

While the GDPR is not the only significant piece of privacy legislation that will affect publishers in the near future—the ePrivacy Regulation90 provides some complementary detail around cookie use, in particular—the GDPR will have global impact, as both a test case and a precedent for increased privacy protection and data collection accountability on the internet. Fortunately for media companies and their audiences, the net effect of these regulations may well be positive in the long term, especially for organizations that cultivate strong reader relationships. Though few may welcome the new complexities the GDPR promises in the near future, eventually it may prove a valuable mechanism for helping rebalance the scales among advertisers, platforms, ad networks, publishers, and audiences.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank staff and fellows of the Tow Center—especially Emily Bell and Abigail Hartstone—for their ongoing support and interest in this project. We would also like to thank the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and School of International Public Affairs, which were our respective home sduring the conception and execution of this report. Finally, we’d like to thank those professionals and experts who so graciously shared their time and insight with us as we attempted to unravel the implications of this important and complex piece of legislation.

Appendix I: Safe Harbor Detailed Definitions

- Notice: Organizations must inform individuals about the purposes for which their information is being collected and used and by whom; individuals must also be provided with information about who and how to contact about inquiries or complaints.91

- Choice: Organizations must offer individuals the opportunity to choose whether their personal information is disclosed to a third party or used for a purpose that is incompatible with the purpose(s) for which it was originally collected or subsequently authorized by the individual. Notably, for sensitive information, individuals must explicitly opt in when personal data is to be transferred to a third party or used for a purpose other than the one for which it was originally collected or subsequently authorized.92

- Onward transfer: “In transferring information to a third party, organizations must apply the Notice and Choice Principles. Third parties acting as agents must provide the same level of privacy protection either by subscribing to Safe Harbor, adhering to the Directive or another adequacy finding, or entering into a contract that specifies equivalent privacy protections.”93

- Security: “Organizations creating, maintaining, using or disseminating personal information must take reasonable precautions to protect it from loss, misuse and unauthorized access, disclosure, alteration and destruction.”94

- Data Integrity: Personal information must be relevant for the purposes for which it is to be used. Organizations should take reasonable steps to ensure that data is reliable for its intended use, accurate, complete, and current.95

- Access: “Individuals must have access to the information about them that an organization holds and must be able to correct, amend, or delete that information where it is inaccurate, except where the burden or expense would be disproportionate to the risks to the individual’s privacy or where the rights of others would be violated. Furthermore, the Safe Harbor principles may be limited to the extent necessary for national security, public interest, or law enforcement requirements.”96

- Enforcement: “Effective privacy protection must include mechanisms for verifying compliance, provide readily available and affordable independent recourse mechanisms in cases of noncompliance, and include remedial measures for the organization when the Principles are not followed. Sanctions must be rigorous enough to ensure compliance.”97

Appendix II: Privacy Shield Provisions

- Handling Europeans’ Personal Data: U.S. companies transferring personal data from the EU must commit to satisfying, robust obligations regarding how that data is processed. U.S. DOC and FTC will monitor and enforce these commitments, and any company handling personal data from the EU must commit to comply with decisions by European data protection authorities.98

- USG Access to Data: The United States has given the EU written assurances that access to information by public authorities for law enforcement and national security purposes will be subject to clear limitations, safeguards, and oversight mechanisms. There will be an annual joint review conducted by the EC and the DOC to ensure that the agreement is functioning—and the first annual review was published on October 18, 2017.99

- Redress: Under the agreement, EU citizens who believe that their data has been misused will have several redress possibilities, and companies to which complaints are directed will have deadlines to respond to such complaints. European data protection authorities may refer complaints to the DOC and the FTC, and for complaints of suspected access to information by national intelligence authorities in the US, a new ombudsperson will be created within the U.S. Department of State.100