Sunil Tripathi was already dead when Reddit famously fingered him as the Boston bomber. Or alleged Boston bomber. Or maybe not the bomber at all, just a guy who looks like the guy the FBI was looking for.

Tripathi wasn’t a bomber, or a suspect. He was a 22-year-old Brown University student who had been missing for a month when Dzhokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev bombed the Boston marathon in April 2013. But three nights after the bombing, he was wrongly accused on Reddit, convicted on Twitter, and vilified on Facebook.

A new film called Help Us Find Sunil Tripathi–the title of a Facebook page created by his family–introduces viewers to Sunil, called Sunny by family and friends, as a boy and later a college student battling depression, and takes them through the events of the night he was briefly identified as a terrorist. By showing us who Tripathi really was, and who he was to his family, the film highlights the cost of shoddy journalism.

The tripathi siblings: Sangeeta, Sunil, and Ravi.

In many of the post-mortems that explored what went wrong, blame was assigned either to social media for its irresponsible speculations, or to the journalists who tweeted or retweeted the rumors. Journalists on Twitter weren’t the only ones acting on the misinformation. Offline, journalists from mainstream outlets, including AP, CNN, Bloomberg, and Reuters did, too. They called the Tripathi family all night, leaving voicemail after voicemail, and sent TV cameras to the family’s Boston home.

Sangeeta Tripathi, Sunil’s sister, received 58 missed calls on her cell phone between 3 and 4 that morning. “My mother kept wanting to answer the phone because she said, ‘What if it’s Sunil?’” Sangeeta says in the film. “I told her, ‘It’s not Sunil.’”

Neal Broffman, a broadcast journalist and the film’s director, had met Sangeeta shortly before Sunil went missing, and had helped the family during the search. The journalists’ behavior that night prompted him to make the film, he told CJR.

At various moments throughout the film, shots of a cell phone lying on a table are accompanied by audio of the journalists’ voicemails. “It’s not a phone call a journalist has to make. It’s actually a phone call a journalist shouldn’t make,” Broffman told CJR, certainly not when based only on hearsay. In one voicemail, a reporter from Talking Points Memo repeats a rumor that spread on Twitter and has never been substantiated as if it were fact: “The Boston Police scanner has identified your brother as a potential suspect in the marathon bombing.”

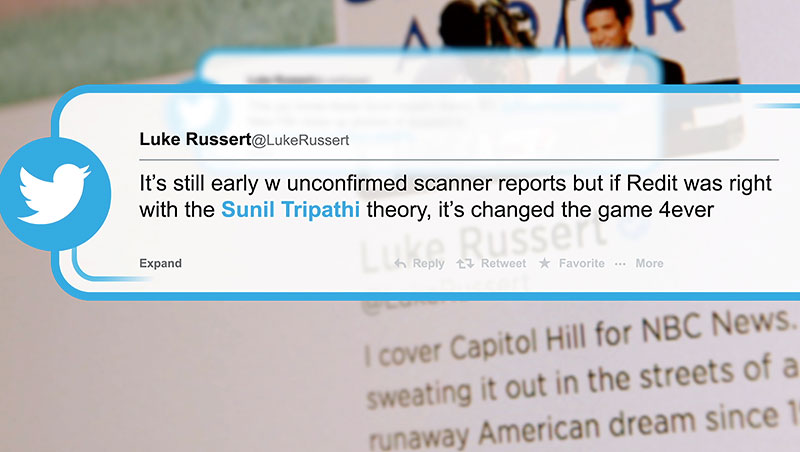

That piece of misinformation began with a tweet, “BPD (Boston Police Department) has identified the names: Suspect 1: Mike Mulugeta. Suspect 2: Sunil Tripathi.” None of it was true. Mulugeta had been mentioned on the scanner, unrelated to the bombing. And his first name wasn’t Mike. The officer had spelled the name, “M as in Mike, Mulugeta.” Tripathi’s name was not mentioned.

Marcus DiPaola, a freelance photojournalist who was on the ground in Boston covering the search for the bombers, watched much of this unfold. “It was a failure to understand how a scanner works,” DiPaola told CJR. He’d found Reddit useful in guiding his reporting during the search, since many Reddit users were listening to police scanners and transcribing what they heard. “It was like having an assignment desk for a freelancer,” says DiPaola. Based on Reddit’s information, DiPaola got shots of the FBI executing a search warrant, and of the National Guards staging area, where hundreds of soldiers were being deployed.

The Reddit users were committed, but they didn’t have journalistic training, so DiPaola shared a few basic principles in a comment, including what’s ethical or unethical to share. Under “Unethical” he wrote “Names of suspects, victims, people who were just in the area.”

A still from the film Help Us Save Sunil Tripathi

“Journalists,” Broffman says, “are supposed to be the firewall between all the noise and something that is trustworthy.” Many failed. On the morning of April 19, the FBI released the names of the suspects. On April 23, Sunil Tripathi’s body was found. He had killed himself more than a month earlier on March 16, the day he went missing.

In the intervening days, the Tripathis called every journalist who had called them and said they were still looking for Sunil. The Facebook page they’d taken down because of the vile social attention they were receiving went back up. Thousands of people around the world joined a campaign to write messages to Sunil on their hands and post photographs of the messages to Facebook. “You are loved Sunil,” they wrote. “You matter.” “Come home.”

Tripathi’s name will forever be connected to the Boston bombing, not as the bomber, but as a cautionary tale for journalists. Getting the story wrong has consequences, even in an age when the error may be as seemingly innocent as hitting retweet.

Chava Gourarie is a freelance writer based in New York and a former CJR Delacorte Fellow. Follow her on Twitter at @ChavaRisa