Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

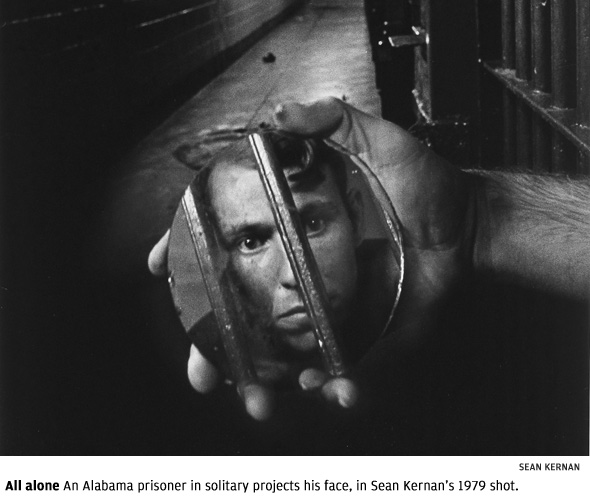

Supermax prisons and solitary confinement units are our domestic black sites–hidden places where human beings endure unspeakable punishments, without benefit of due process in any court of law. On the say-so of corrections officials, American prisoners can be placed in conditions of extreme isolation and sensory deprivation for months, years, or even decades. At least 80,000 men, women, and children live in such conditions on any given day in the United States. And they are not merely separated from others for safety reasons. They are effectively buried alive. Most live in concrete cells the size of an average parking space, often windowless, cut off from all communication by solid steel doors. If they are lucky, they will be allowed out for an hour a day to shower or to exercise alone in cages resembling dog runs.

Most have never committed a violent act in prison. They are locked down because they’ve been classified as “high risk,” or because of nonviolent misbehavior–anything from mouthing off or testing positive for marijuana to exhibiting the symptoms of untreated mental illness. A recent lawsuit filed on behalf of prisoners in adx, the federal supermax in Florence, CO, described how humans respond to such isolation over the long-term. Some “interminably wail, scream, and bang on the walls of their cells” or carry on “delusional conversations with voices they hear in their heads.” Some “mutilate their bodies with razors, shards of glass, sharpened chicken bones, and writing utensils” or “swallow razor blades, nail clippers, parts of radios and televisions, broken glass, and other dangerous objects.” Still others “spread feces and other human waste and body fluids throughout their cells [and] throw it at the correctional staff.” While less than 5 percent of US prisoners nationwide are held in solitary, close to 50 percent of all prison suicides take place there.

After three years of reporting on solitary confinement for Solitary Watch, a website I co-founded, I’m convinced that much of what happens in these places constitutes torture. How is it possible that a human-rights crisis of this magnitude can carry on year after year, with impunity?

I believe part of the answer has to do with how effectively the nature of these sites have been hidden from the press and, by extension, the public. With few exceptions, solitary confinement cells have been kept firmly off-limits to journalists–with the approval of the federal courts, who defer to corrections officials’ purported need to maintain “safety and security.” If the First Amendment ever manages to make it past the prison gates at all, it is stopped short at the door to the isolation unit.

As a reporter, I ran into solitary confinement three years ago in writing an article about Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox, members of the so-called Angola 3, who have lived in solitary confinement in Louisiana since they were convicted of killing a prison guard in 1972. After writing an initial article about the case, based on public records, I sought permission to visit Angola and interview the two men. I was told by a deputy warden that the prison wanted nothing to do with me, because officials didn’t like what I had written. The ACLU of Louisiana took up my case, gathering evidence to show that while the prison denied me entrance, it had welcomed many others, including press, politicians, religious figures, schoolchildren, tourist buses, Hollywood filmmakers, canoeists paddling past on the Mississippi, and such notables as Miss Louisiana. Since Angola had such an open-door policy, its discrimination against me was actionable. Warden Burl Cain backed off and granted me what turned out to be the standard guided tour of the plantation prison. It included numerous dormitories, chapels, and even the death chamber–but not the solitary confinement units. Even the ACLU couldn’t help me penetrate those fortresses of solitude.

It would be the first of many times I was turned away from such units. While reporting on solitary confinement in New York State, I was readily shown around Auburn Correctional Facility by the affable warden there. I saw all kinds of cells, yards, and workshops–everything but the so-called Special Housing Unit (SHU) where prisoners are held in solitary. These units, I was told, are never shown to the media. At another New York prison, I managed to visit (under the watchful eye of a guard) with a man who has been in solitary for nearly 25 years. Since the Department of Corrections media policy forbids media visits to prisoners in “segregation,” I had to withhold the fact that I was a reporter, and sign in as his “friend.”

Once I launched Solitary Watch, I learned of a handful of other reporters who were encountering the same restrictions–and working around them and in spite of them. “I was never able to get inside” a SHU in New York, Mary Beth Pfeiffer, a reporter for the Poughkeepsie Journal, wrote in an email. “In 2001, after I began writing about links between solitary confinement, mental illness, and suicide, they refused even to let me into any of their prisons except through the visiting room. Even there, I once had my notes seized by prison officials who claimed note-taking was not permitted.” Pfeiffer says she relied on “official reports of conditions and suicides there, and the accounts of former prisoners.”

George Pawlaczyk and Beth Hundsdorfer of the Belleville News-Democrat authored a series of articles called “Trapped in Tamms,” about the supermax prison in southern Illinois. The 2009 series, which won a George Polk award, revealed horrendous treatment of mentally ill prisoners and the cruel attitudes of the prison officials, including doctors. Unable to secure a visit, Pawlaczyk says their reporting was based largely on court documents, mostly depositions, and the surprise finding that one Illinois county’s mental health reports were filed and open to the public.

Susan Greene, the former Denver Post reporter who in 2012 wrote “The Gray Box,” a blistering report focusing on ADX, for the Dart Society, says she couldn’t even get close to the prison, which has been completely off-limits to the press since 9/11. “I have had absolutely no access to the place at all,” she told me. When she pulled up in front of the driveway to the remote prison complex, she was chased away by armed guards. But in addition to public records, Greene based her reporting on correspondence with prisoners in extreme isolation, carried on over more than a year. Ironically, once her article was published, she could not send it to her correspondents in ADX, due to a policy against allowing prisoners’ names in an article. “So I redacted all the prisoners’ names,” she said, “and then it came back saying something like, ‘You can still see it if you hold it up to the light.’ Out of frustration and wanting to be a pain in the ass, I Exacto-knifed out all the names and sent it, and it still didn’t get through.”

Shane Bauer, who wrote a 2012 expose about solitary confinement in California for Mother Jones, also relied heavily on correspondence with dozens of prisoners in Pelican Bay and other state SHUs who had staged several highly publicized hunger strikes after years or decades in isolation. Bauer spent more than two years in an Iranian prison after being captured on the Iran-Iraq border, including four months in isolation, and thus has the rare perspective of someone who has himself experienced solitary. He also succeeded in gaining access to Pelican Bay, though it was severely limited and carefully orchestrated. Bauer says he was taken to a unit full of men who had cooperated with prison officials by passing on information about prison gangs, “and was allowed to interview one inmate while the gang investigator stood by.” Visits to the solitary cells were refused, as were interviews by the warden and top corrections officials.

Lance Tapley began writing about solitary confinement for the Portland Phoenix seven years ago, when a supermax prisoner named Deane Brown got in touch with him. Brown “wanted to expose to the outside world the torture he was experiencing and seeing in the Maine State Prison’s Special Management Unit,” Tapley wrote to me. Initially denied access to SMU prisoners, Tapley was able to convince the governor’s office to intervene. Then he was allowed to interview several men “in hand and foot shackles on the other side of a Plexiglas window.” Those six interviews and a leaked official videotape of a cell extraction, plus interviews with the corrections commissioner, defense attorneys, and others, formed the basis of his first supermax stories. Once those stories were published, Tapley was banned from the prison. And like many prisoners who talk to the press, Deane Brown faced retaliation: He was shipped to a prison out of state.

Where journalists have succeeded, one way or another, in penetrating the black sites, their reporting has undeniably had an impact. In Maine, it helped spark a grassroots movement and a legislative initiative, which eventually spurred the prison system to reduce its use of solitary confinement. In New York, it became ammunition in a battle to keep mentally ill prisoners out of solitary. And in Illinois, it provided fuel for an effort that has convinced the governor to shut down Tamms supermax prison.

The stories have been effective. But their scarcity also suggests that the lack of press access to these sites around the nation has stifled public debate on a significant issue of policy and human rights. “Solitary confinement is a brutal form of prison punishment that has claimed many lives and caused untold suffering,” says Mary Beth Pfieffer. “That is the story that officials do not want told.” Until we are allowed to tell it properly–until we can visit solitary units ourselves, and speak unhindered with prisoners and corrections officers–we cannot fulfill our duty to shine a light into society’s darkest corners.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.