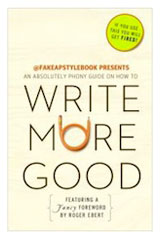

Write More Good: An Absolutely Phony Guide | by The Bureau Chiefs | Three Rivers Press | 272 pages, $13.00

Just one day after it launched in 2009, @FakeAPStylebook, the Twitter-based satire of the AP’s (in)famous usage manual, had 10,000 followers. Five days after the launch, it had amassed 30,000—surpassing, in the process, the real AP Stylebook Twitter account. By January of 2010, following in the footsteps of be-sitcommed handle @shitmydadsays, the @FakeAPStylebook feed—and the vaguely anonymous collective of “Bureau Chiefs” who ran it—had scored a book deal.

As the Bureau Chiefs write in the product of that arrangement, the just-released Write More Good: An Absolutely Phony Guide: “Facebook? Tumblr? Digg? These are not worthwhile subjects, and neither are their peers. Except for Twitter. Did you know you can get a fucking book deal just by writing some jokes on Twitter?”

As the Bureau Chiefs write in the product of that arrangement, the just-released Write More Good: An Absolutely Phony Guide: “Facebook? Tumblr? Digg? These are not worthwhile subjects, and neither are their peers. Except for Twitter. Did you know you can get a fucking book deal just by writing some jokes on Twitter?”

You sure can! The question, though, is whether you can get a good book out of the deal. Can a clever Twitter feed translate into a similarly clever print product?

In some sense, the answer to that question is, really, “Who cares?” Because actually reading the book—sitting down with it and curling up with it, beside a roaring fire or whatnot—seems, somehow, beside the point. Write More Good is an artifact as much as a piece of literature, the kind of thing you might find displayed on a table in the Ironical Kitsch section of Urban Outfitters, piled next to Awkward Family Photos and a picked-over array of Mr. T bobbleheads. The book’s physicality—the fact that it exists in the first place—is itself part of the joke.

Write More Good is the kind of book, in other words, that is there to be seen as much as read. (Its tagline: “If you use this, you will get FIRED.”) And the book’s context—the fame of the @FakeAPStylebook Twitter feed, the speed of its Web-to-book trajectory, the simple symbolism of a new medium being siphoned up into an old—is a crucial element of its content. At least half the humor of Write More Good comes by way of its concept—which means, if my math’s right, that the book’s actual contents can be a maximum of 50 percent funny.

(When opining, disguise poor logic with math—preferably math that involves percentages.)

So—with the significant caveat that it’s hard to think of any situation save for a book review that would lead one to hunker down, fireside, with Write More Good, devouring the literature contained within—let’s talk percentages. If the universe of Funny Things can be neatly divided according to the reactions those things elicit—the “HA!” versus the “heh”—then Write More Good breaks down to about 20 percent “HA!” and 80 percent “heh.” As it explores topics like Science (“and the Blinding By Thereof”), Media Law (“You Are So Screwed”), and Punctuation and Grammar (“LOL”), the book certainly has spurts of funniness. (“When plagiarizing, be sure to use the word ‘reportedly.” And also: “Use ‘disgraced politician’ on first use, ‘expert political analyst’ on later mentions.” And also! “Laissez-faire: Alan Greenspan’s safeword.”)

Awesome. I’d totally retweet that. But, then, there’s also:

“Absolute privilege: Enjoyed by the inhabitants of Cape Cod, Hyannis Port, and Bill Clinton’s orbiting space fortress.”

And:

“In the twenty-first century the reporter with his press card-adorned fedora and notepad has given way to a guy in a laser-etched bubble helmet holding a Venusian calculotron.”

And:

“Scoop: Using a discarded newspaper to pick up your dog’s poop during walksies.”

(GOL: Groaning out loud. See also: “Eye rolling,” “ennui,” “loss of precious seconds of one’s life to the yawning abyss of eternity.”)

The jokes here, across 272 pages of faux-nology, tend to return to the same predictable punchlines: Bloggers are morons! Reporters are drunks! Politicians are jerks, and probably gay! Ladies are secretaries, and hopefully slutty! Which, you know: Heh. (Though, of course, it could well be that Write More Good is actually 100 percent witty and 200 percent satirical, making it, obviously, 300 percent hilarious…and that it is your correspondent, not the book, who is lacking in humor. So caveat FakeStylebooker, and everything.)

Anyhow, 20 percent funny, it’s worth noting, isn’t half bad considering that 90 percent of Write More Good‘s content is original—that is, not simply repurposed from the @FakeAPStylebook Twitter feed. “I would like to praise the authors for not doing what anyone else in the Internet Age would have done, which is simply cutting and pasting together a slew of tweets, calling it a book, and raking in the dough from Old Media,” Roger Ebert, an expert in both Twitter and Old Media, writes in the book’s introduction.

And, totally: The Bureau Chiefs could have easily compiled their feed’s 1,000+ tweets into a document, bound the thing up, and called it a day. Instead, they’ve created an almost wholly new set of short entries while also expanding their purview beyond simple style notes—the bread and butter of the Twitter feed—and into longer, actual-AP Stylebook-like explanations about the coverage of political campaigns, sports, the future of the news industry, etc. It’s an ambitious, and in that admirable, undertaking.

But a consequence of The Bureau Chiefs’ literary moxie is that @FakeAPStylebook, expanded into Write More Good, becomes less “joke told in 1,000 parts, with 1,000 different punchlines”…and more one big meta-joke, with a single, ongoing punchline. (“We wanted it to not be an Internet book per se but a real comedy book that had some depth to it,” Ken Lowery, Write More Good‘s co-editor—and one of its fifteen writers—explained.)

But, then, depth isn’t an unalloyed good. Twitter isn’t just an infrastructure; it’s also, to some extent, an insulation—from verbosity, from complexity, from, generally, high expectations. Narrative platforms vary not just in length, but in form (Marshall McLuhan: Wannabe journalist known principally for his cameo in “Annie Hall”); the jokes coming from @FakeAPStylebook—the feed, now at 200,000+ followers, is still going strong—feel ad hoc and organic. And so does the audience interaction with them. If the tweets are funny, they might elicit a chuckle; if they’re really funny, a retweet. And if they’re neither of those…hey, no harm done. Twitter, free and easy in pretty much every sense, is the ultimate low-stakes environment—for both the producer of content and the consumer of it.

Not so for a book, though, which carries into every transaction the luggage of intellectual and financial expectation. Which is another way of saying that poop jokes printed in a book are different from poop jokes posted to Twitter. As a feed, dynamic and ephemeral, @FakeAPStylebook—its humor popping up, fully formed, between breaking-news updates and friends’ Foursquare check-ins—is a treat, subversive and surprising and satirical all at the same time. The tweets catch you off-guard, in a good way. They’re like being Rickrolled by E.B. White himself.

In book form, though, in the aggregate, the subversive and surprising and satirical become sort of…sad. Without the benefit of Twitter’s enforced brevity—not to mention its levity—the meta-journalistic humor becomes a little too sharp, a little too raw, a little too awkward; it’s as if Mr. White, having had one cocktail too many, has suddenly backed you into a corner, forcing you to listen as he shouts about the sorry state of contemporary journalism. In the alchemy that spins tweets into Gutenbergian gold, irreverence gives way to, of all things, bitterness. “Fourth Estate: A term journalists use to make themselves feel like they make important contributions to society so they don’t eat a gun after covering their twentieth ham-and-beans fundraiser.” And then: “Do not use emoticons in headlines or the body of your text. If for some reason your story is about actual emoticons, please kill yourself.”

Funny? I guess. But also: :-(

Click here for a complete Page Views archive.

Megan Garber is an assistant editor at the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University. She was formerly a CJR staff writer.