Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Remember one year ago when then-Attorney General Eric Holder supposedly tightened restrictions on the Justice Department so it could not easily conduct surveillance on journalists’ emails and phone calls? Well it turns out the Justice Department inserted a large loophole in its internal rules that allows the FBI to completely circumvent those restrictions and spy on journalists in secrecy—and with absolutely no court oversight—using National Security Letters.

And what, exactly, are the Justice Department’s rules for when they can target a journalist with a National Security Letter (NSL)? Well, according the government, that’s classified.

For those unfamiliar with NSLs, they are a particularly pernicious and controversial surveillance order that the FBI can serve on internet and communications providers to demand all sorts of digital information without any oversight from judges or courts. Worse, NSLs almost always have a gag order attached to them, preventing the phone or email companies not only from telling the target of the NSL that he or she is under surveillance but from publicly acknowledging they received an NSL at all. Various aspects of NSLs have been ruled unconstitutional in the past (including in a case still ongoing), but because of slight changes by Congress and the courts, they still persist.

In July 2015, Freedom of the Press Foundation—the organization I work for—sued the Justice Department under the Freedom of Information Act, seeking disclosure of the secret rules governing the use of NSLs to conduct surveillance on reporters. Over the past few weeks, we’ve received documents back from the government in response to the lawsuit that shed a little light on how the letters are used.

The crux of this case dates back to 2013 and 2014, when the Justice Department was stung by a public backlash over the outrageous surveillance the agency conducted on Associated Press and Fox News reporters while investigating reporters’ sources. At the time, the Justice Department had secretly subpoenaed over 20 AP phone lines affecting more than 100 AP journalists in search of a leaker, without notifying the AP until after the surveillance was over. In a separate case, the Justice Department got access to Fox News reporter James Rosen’s Gmail account and alleged in court documents that he was “aiding and abetting” violations of the Espionage Act.

In response to intense criticism from news organizations, Holder vowed to update the agency’s “media guidelines,” which lay out when and how the government can obtain the phone or email records of journalists with subpoenas, warrants, and other types of court orders.

Over the next year the Justice Department altered its guidelines on two occasions; apart from a few quibbles, the changes seemed like big step forward. They raised the bar for when and how the government could conduct surveillance on reporters and (hopefully) would prevent what happened to the AP and Fox News from happening again.

But here’s the loophole: Holder’s changes to the media guidelines had no effect on using NSLs to spy on the communications records of journalists, because the guidelines don’t cover NSLs at all. As the Times’ Charlie Savage reported:

There is no change to how the F.B.I. may obtain reporters’ calling records via “national security letters,” which are exempt from the regular guidelines. A Justice spokesman said [NSLs are] “subject to an extensive oversight regime.”

We filed a FOIA request based on this reference in The New York Times (plus a redacted report the Justice Department had released earlier in the year), asking for the “extensive oversight regime” governing NSLs aimed at journalists to be made public. The Justice Department didn’t respond to our request for months, so in July, we sued.

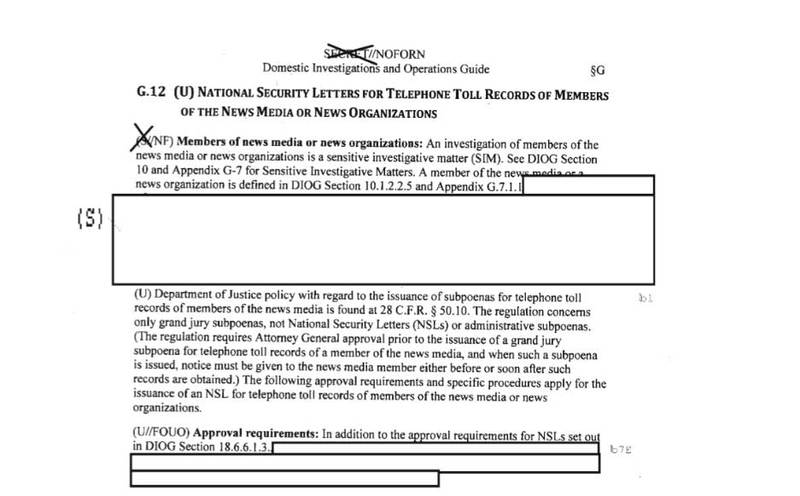

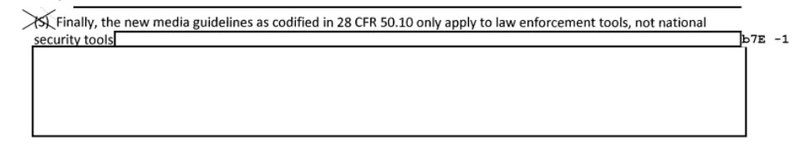

Over the holiday break, we received two batches of documents from the Justice Department. In the released material–which includes Justice Department emails, training presentations and part of the agency’s internal rules for conducting investigations–the government confirms that the media guidelines “only apply to law enforcement tools, not national security tools,” and that those national security tools include NSLs, as well as secret FISA court orders.

The documents–which you can read in full here–also confirm that the Justice Department’s rules for issuing such surveillance orders on journalists are classified. The government has redacted the rules in emails that reference them. Shamefully, the government is still claiming that those rules should remain secret.

A redacted page in the Justice Department’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide (DOIG) makes clear the government can spy on journalists with NSLs while circumventing the Attorney General’s media guidelines

It’s not just a hypothetical worry that the FBI will use NSLs to spy on journalists. The government itself–in heavily redacted Inspector General reports–has admitted to using NSLs to conduct secret surveillance on unnamed New York Times and Washington Post journalists during the George W. Bush administration. Three-time Pulitzer-winning reporter Barton Gellman revealed in 2014 that he had been told that his phone records were also obtained by the government using an NSL.

And it’s quite possible there has been more surveillance we just don’t know about, given that hundreds of thousands of NSLs have been issued in secrecy since 9/11.

Given that all federal leak prosecutions in the past decade that have involved the surveillance of journalists were national security cases, why should the revised media guidelines comfort journalists at all? Instead of having to follow the strict media guidelines, instead of serving subpoenas or warrants, the FBI and Justice Department can simply use NSLs and FISA court orders under even more sweeping secrecy rules than they did in the AP and Fews News cases.

These are just the first documents we‘ve received in this lawsuit. Freedom of the Press Foundation will continue to fight until the Justice Department releases its secret rules for targeting members of the media with national security orders.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.