Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

I’m about to celebrate my one-year anniversary as a podcaster. I started a show with two of my friends (one is my co-host, the other is our producer) last year because we noticed that more and more people were talking about and listening to podcasts, and we wanted to figure out what makes the medium tick. In some ways, being only a year deep into this endeavor makes us newbies—after all, podcasts have been around for a decade. In other ways, we’re established—we’ve built a big enough audience that we can start selling ads. Also, we’ll always be able to say we started podcasting before Serial blew up.

For a long time, podcasting has been both old hat and the next big thing. “In a nascent state, podcasting is the platform du jour, the latest form of jailbreak media that has plain old citizens pulling up the microphone and mainstream media running scared,” David Carr wrote in 2005. Since then, niche audiences like tech insiders and comedy fans have remained devoted to podcasts. But most of us paid little attention to the medium. Just last year, Pew’s State of the Media report concluded that the audience for podcasts had “largely leveled off” and that only 29 percent of Americans had ever listened to a podcast.

Now there’s an industry-wide sense that the podcast is on the cusp of revival. The journalists and entrepreneurs who have staked their professional future on podcasting point to a few reasons why: There’s a growing audience thanks to in-car technology that makes on-demand listening as easy as tuning in to traditional radio. There’s a podcast app that comes standard on all iPhones, meaning more people are inclined to subscribe to shows and give them a listen when they see a little notification pop up that there’s a new episode. And then there’s the runaway success of Serial, podcasting’s first megahit, which garnered more than 5 million listeners—numbers that rival some cable TV shows.

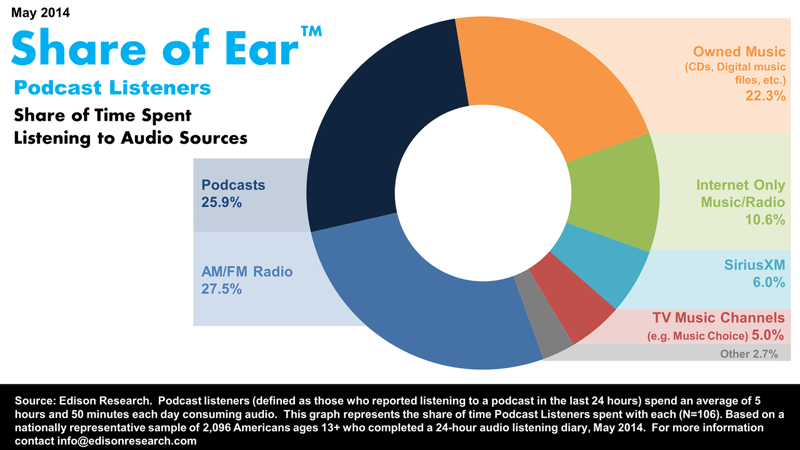

But the real reason established media companies are starting to take podcasts seriously has more to do with the nature of their listeners. Podcast consumers, according to Edison Research, listen to an average of six episodes per week. Once they find a podcast they like, they tend to be devoted. The medium feels intimate. Unlike the audience online, which tends to click through and then bounce away quickly, podcasts draw people in for the duration of the episode. They feel a deep, personal connection with the hosts. In an era when other ad rates are plummeting and publications are trying to position themselves as membership organizations, this level of fervent fandom is something that most media outlets would kill for.

For media companies that were slow to adapt to digital and weary of constantly generating page views to compensate for sagging ad rates, podcasts present both a do-over and a new opportunity: Could this be a medium that’s financially viable? To understand how they might make money in the future when the audience is presumably even bigger, it makes sense to look at how podcasts are making money now.

The barriers to entry are famously low—indeed, I podcast from my closet, using a high-quality microphone I bought for $119 and software I downloaded for $49. But even though our producer has years of radio producing and editing experience, our podcast is, admittedly, still rather amateurish. The equipment and editing talent required to make more professional shows is significantly pricier. To cover production costs, most podcasts rely on a combination of listener donations, ad sales, and, increasingly, premium or bonus content that’s available only to paying subscribers. (In the tech world, this last model is referred to as “freemium.”) They’ve also organized into networks of shows with similar styles or subject matter so they can sell ads, share resources, and cross-promote to each other’s audiences.

Public radio has long relied on the pledge-drive model, and many podcast hosts make direct pleas to listeners on an annual basis, or when they want to expand. In 2012, the design podcast 99% Invisible became the most-funded journalism Kickstarter in the crowdfunding site’s history. Since then, host Roman Mars has gone on to create Radiotopia, a network of storytelling podcasts that are also aired on traditional radio through Public Radio Exchange. Other networks, like the comedy-oriented Maximum Fun, have a semi-annual fundraising drive, with a portion of the proceeds distributed across all shows in the network.

Some podcasters have gone after venture capital. Courting investors in his new podcast network Gimlet Media was a big plot point in the first half of Alex Blumberg’s StartUp podcast. But VC money is not a way of generating income off the product, or making an actual profit.

A few of the more established podcasts, like WTF with Marc Maron (who’s been podcasting since 2009) and The Dawn and Drew Show (which has been around since 2004), have gone “freemium,” charging subscribers for access to premium content, such as archival episodes, an extra episode each week, or bonus interviews.

But most podcasts, even those that are also fundraising or offering paid premium content, have adopted a pretty traditional ad-sales model—with a few twists. If you’ve ever listened to a podcast, you’ve probably heard custom pitches for companies like Mail Chimp, Audible.com, Squarespace, Nature Box, and Stamps.com. This “native ad” model, which causes so much handwringing in print and digital, is actually a pretty natural fit on podcasts. The host casually inserts an endorsement, often for a web-based business or a tech product like email newsletter services. Because podcast listeners are still mostly early-adopters of technology, many podcast advertisers are tech-oriented businesses interested in direct conversions. The podcast’s host usually directs listeners to a sponsor’s website and urges them to use a certain code when purchasing the product.

Direct-response advertisers, those that are always looking for ways to measure the number of new customers they are reaching, love being able to use codes and surveys. Other “brand advertisers,” who are less interested in tracking which sales come from which podcast, are more like billboard buyers or radio sponsors of the past. They just want to get their name out there. They’re less common in the podcast world, but a growing group. And they don’t seem particularly troubled by the fact that podcast listener measurement tools are, as several people described them to me, more of a blunt instrument. Whereas web advertisers can see exactly who viewed their ad—and who clicked and whether they went on to buy anything—podcast analytics are notoriously murky. Just because someone downloads a podcast doesn’t mean they listen to it, and there’s no way to track who’s merely started an episode and who’s heard it all the way through.

Despite the fuzzy metrics, or perhaps because of them, right now podcast ads are expensive. According to one recent estimate, podcast ads are selling for $20-$45 per thousand listeners—a number known, in ad-sales parlance as CPM. That’s far more than either radio, network tv, or web ads, which tend to have CPMs in the $1-$20 range. There’s a Catch-22 with these high podcast CPMs, though. Right now most podcast audiences are (relatively) small and devoted. Listeners feel a special connection with the host, and probably only listen to a handful of shows, so the personal ad pitch works really well. But does that special listener-host relationship start to fade away as a podcast grows in size? I feel like I know the hosts of The Read, one of my mainstays, but not Ira Glass, who is by now not merely a host but an audio archetype. And does this personal-endorsement model work for journalistically minded podcasts? Reply-All, a new reporting-oriented podcast about digital culture, got into trouble when, as part of an advertisement, it interviewed a kid who uses Squarespace. The problem was that his mom was under the impression the interview was for This American Life, not an ad. Oops.

These hiccups haven’t diminished podcasters’ confidence in their financial future. And for some advertisers who have been sponsoring podcasts since before the Serial rush, the ground is shifting beneath them. “I can definitely feel it changing,” says Ryan Stansky, who manages the media-buying team at Squarespace, which advertises on about 100 podcasts and has been advertising on podcasts for five years. “You can see how the relationships change from partner to partner. Some say, there’s more demand, we should raise prices. There was one partner who is already selling 2016 inventory. I’m like, this is insane. We’re not going to commit to 2016 right now.”

One thing that separates the modern hopes for podcasting from the predictions of 10 years ago is that now podcasts are getting organized. They’ve banded together in affiliate networks to cross-promote and share resources. Comedy and chat podcast networks like Earwolf, Maximum Fun, and Nerdist have been around for awhile. But in the last year, more journalistically oriented networks have sprung up, too. Radiotopia was Kickstarted into existence, making several shows and getting them on traditional radio via PRX. This American Life alum Alex Blumberg chronicled the founding of his network Gimlet Media on his StartUp podcast. And then Slate announced it was expanding its own considerable podcasting efforts to produce shows for other big media brands, too, under the network name Panoply. “The business has been going well for us for the last few years, we’ve been selling lots of ads and paying for our shows as we go,” says Panoply’s chief content officer, Andy Bowers. “The audience for podcasting is the most engaged I’ve ever seen in nearly 30 years in broadcasting, and advertisers are starting to notice the same thing.”

That doesn’t mean there aren’t detractors. “Podcast networks are like record labels: they promise exposure, tools, distribution, and money,” wrote Marco Arment, a programmer and entrepreneur who created, among other things, the podcast-listening app Overcast. “But as the medium and infrastructure mature, their services are often unnecessary, outdated, and a bad deal for publishers.” To be fair, he wrote that in June of last year, before Serial’s success made podcasting so attractive to big media brands. And even he would seem to agree that even if a podcast remains nominally independent, it’s helpful to have someone else selling ads for you. One podcast network, Earwolf, created Midroll, an ad-sales network to sell sponsorships for both its own podcasts and those that aren’t on the network.

Of course, all of this is moot if your podcast has fewer than 50,000 downloads per episode—which is generally seen as the threshold a podcast needs to cross in order to attract advertisers. “Your view of the ad part of the equation depends on where you’re sitting,” says Erik Diehn, vice president of business development at Midroll Media, which sells ads on behalf of about 200 podcasts. “If you’re the host of a successful podcast with download numbers in the six figures and you’re successfully monetizing because you’re going through someone like us, you’re pretty happy with the state of the world. If you have a small podcast, you’re probably a little more worried.”

If you’re relatively small, finding an audience and getting paid can present a challenge. Most podcasters—those on the opposite end of the spectrum from Serial, the most successful podcast in history—are hobbyists who dabble in lots of different types of media, says Nicholas Quah, author of the regular Hot Pod newsletter. He likens it to blogging. “When I think about how the money flows, chances are that a very small number of people are able to make a full living just making one or two podcasts,” he says. Max Linsky, who cohosts the Longform podcast, echoed that analogy: “I think podcasts are gonna be like blogs were a few years ago: Everyone starts a podcast and does a couple episodes and fades out.” There are some glimmers of hope—ACast, a Swedish podcast-hosting company, has an app that runs short ads at the beginning and end of each podcast. They sell ads against podcasts of all audience sizes, and offer podcasters a 50-50 revenue split—which means that even podcasters with a few thousand listeners could make a little cash. The app is popular in Sweden, and they’re planning to launch in America soon.

For listeners, the podcast boom presents both hope and frustration. The iTunes podcast app is the primary way listeners get their podcasts—it’s where more than half of all podcast downloads happen, with Stitcher and Soundcloud trailing behind. There are a lot of podcasts out there, but after listeners binge on one, iTunes doesn’t do a great job of directing them to what they might want to download next. It’s notoriously difficult to share audio on social media. It seems like this chaos would be an impediment to gaining listeners. But for podcasting networks like Gimlet, Panoply, Radiotopia, and Earwolf, this is an opportunity.

Networks are betting that an endorsement from a trusted host is a way to guarantee that the new podcasts they start will be successful. Earwolf, a network of mostly comedy podcasts, has between 300,000 and 400,000 listeners across its more than 50 shows. If it launches a new podcast hosted by someone who’s been a guest on one of its existing hits, it can expect 30,000 listeners for the show, right off the bat, says Diehn. Which means it’s already of interest to advertisers. The most extreme example is what several podcasters call “the Ira Glass bump.” In case you can’t guess, that means if your show is featured on This American Life you can expect a massive increase in listeners. Blumberg’s investors in Gimlet Media referred to his This American Life connection as his “unfair advantage.”

Right now, “it’s a lot easier to get someone to go from one podcast to another podcast than it is to get them to go from listening to no podcasts to listening to your podcast,” says Matt Lieber, Blumberg’s Gimlet cofounder. But presumably, the listening hours of existing podcast fans will be maxed out at a certain point. If the short-term question is how to get your podcast into the ears of someone who already likes podcasts, the long-term question is how to get podcasts into the ears of someone who doesn’t already listen to podcasts. More and more people are listening in their cars. And it helped that iTunes recently created a separate app for podcast listening. But podcasts still tap only a fraction of the audience that other media reach.

This is why you can expect to see more established media companies dabbling in podcasting—not just those like The New York Times. BuzzFeed is set to launch its first podcasts this month, and audio director Jenna Weiss-Berman says the focus is on content first and not monetizing the shows. But the fact that podcast analytics are so murky could present a challenge to media outlets that are accustomed to showing advertisers exactly who has clicked on what and for how long. “For a place like BuzzFeed that’s really measurement obsessed, to not be able to really measure podcasts is obviously a big problem,” Weiss-Berman says.

Until all this is sorted out, it’s still the wild west. “It is naive and wrong to describe it as anything other than really, really early. The technology is still terrible. The distribution is pretty broken. And I don’t think anyone’s got it figured out yet,” Linsky says. “But the level of investment is about to be higher than it’s ever been. And someone, somewhere, is going to want to see a return on that.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.