Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Nearly 40 years ago, a young journalist just out of Stanford traveled to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North and South Dakota and started a newspaper. That reporter, Bill Grueskin, would run the Dakota Sun for two years, the first step in a news career that would lead him to The Miami Herald, The Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg News.

That was in 1977. Last year, his daughter, Caroline, landed her own first newspaper job, at The Bismarck Tribune, where she quickly found herself in the middle of covering the protests over a proposed pipeline at Standing Rock, literally retracing many of her father’s early journalistic steps.

Bill Grueskin, 60, now a professor of professional practice at the Columbia Journalism School, and Caroline, 24, (whose mother, Rosalind Resnick, is also a former Miami Herald journalist) sat down recently with CJR Editor and Publisher Kyle Pope to talk about the synchronicity of their careers, how a father responds to his daughter’s Internet trolls, and the pride they both have in each other’s work.

***

CJR Bill, what brought you to North Dakota?

BG I graduated from Stanford with a degree in classics. And I had done a few journalism jobs or internships, one in Palo Alto, one in Italy at an English-language paper, and I’d always found each newsroom had these old guys who would sit around and say, “One day I’m gonna leave this place and go work on a little paper of my own.” And I thought, OK, I’m gonna get that out of my system early.

So I called VISTA–the domestic version of the Peace Corps–and said, “Do you ever need someone to start a newspaper or run one?” And they said, “That never happens.” Then, a couple weeks later I got a call from the head of VISTA in Denver, who said that there’s an Indian reservation that wants somebody to start a newspaper. He said “Standing Rock.” I’d never heard of it and it took me about 15 minutes to find a map that had it. A couple of months later I got in my Jeep and drove to Standing Rock.

CJR And you started the newspaper there from scratch?

BG There was nothing there. My sponsoring organization was a community college, and the president of the college, a guy named Jim Shanley, had this vision for how it would be good for the college and good for the community if there was a paper that covered Indian affairs.

Standing Rock in those days had 10,000 people. It was half Anglo and half Native American. And there was a white-run newspaper in a nearby town but they never did stories about the tribe or tribal issues.

CJR And the paper was called the Sun?

BG Yeah, the Dakota Sun. It was eight to 12 tabloid pages and came out every Thursday afternoon. At the beginning, we raised money by selling hot dogs at a pow wow at the end of August. I drove up to Bismarck and bought 1,200 hot dogs, thinking we’d sell them for a dollar each. It was a three-day pow wow and by the second day, we had sold about 80 hot dogs. So, I was looking at about 1,100 hot dogs in my freezer. What I didn’t realize is by the third day, most people are starting to run out of money, and we sold the other 1,100 hot dogs at cut rate. We ended up making $800 or $900 and that was enough to get us started.

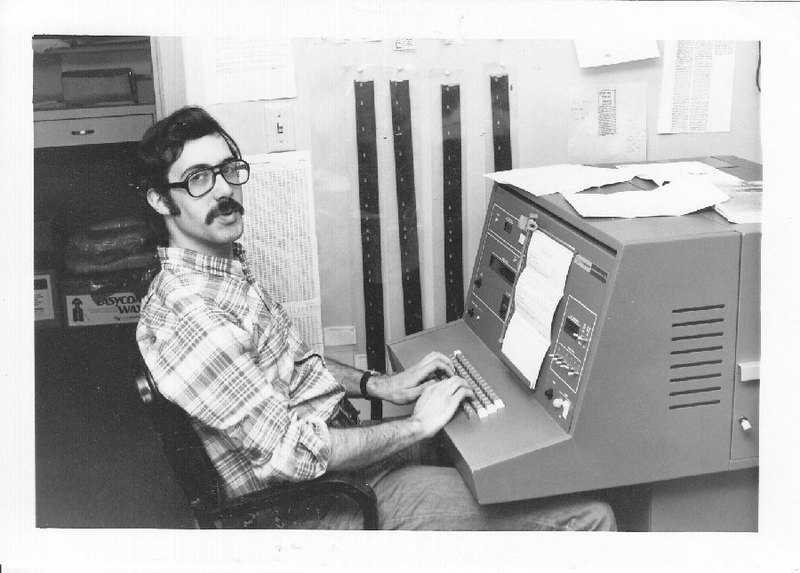

Bill Grueskin trying out the Dakota Sun‘s new typesetter in 1978, made possible after the Sun won the official-newspaper election in Sioux County, North Dakota.

CJR What did you cover?

BG Pretty much everything a small weekly newspaper would cover. We would occasionally take an issue broadly framed around Indian affairs and localize it. So, at the time, there was a lot of negotiation over a settlement over the Fort Laramie treaty, the one that gave the Black Hills to Indian tribes. That was a local issue for us.

We covered tribal council meetings, we covered crime. We’d do a recipe column based on commodity food. People would get these huge hunks of cheese, so we would do a recipe every week. Mostly melted cheese on rice or beans or some variation thereof.

CJR When you look back, other than it being a great experience, are you proud of the work? Was it good journalism?

BG Yeah, I thought it was. I remember there was a livestock program where the government gave a bunch of cattle to local Indians to get them started as ranchers, but they didn’t give them the proper infrastructure, and the cattle died during a blizzard. I still have those pictures of dozens of frozen cattle corpses with their hooves up in the air. It was an interesting story because it got at a well-intentioned government program going nowhere, leading to a lot of disappointment among both the tribe and the government.

CJR And what was life like there? Was it isolating?

BG It’s a hard place to live. In the winter the unemployment rate was about 85 percent. The alcoholism rate among men was over 50 percent. And the winters there are just incredible. Once, I’d been gone for a few days from my little house and one of the windows had broken out. And when I returned, there was a huge mound of snow in the living room. I had turned the faucet on in the kitchen to keep the pipes from freezing and it turned into a frozen waterfall. So, you had the big snowbank in the living room meeting the frozen waterfall from the kitchen.

CJR After you left there, you went on to your career elsewhere. In your personal career narrative, how dominant a role does this play?

BG It was a pretty central experience. When you’re running a small paper, there’s no disassociation between you and your readers and the impact of your stories. One time I was in the local grocery store and I felt someone hit me in the back. I turned around and I said, “Why did you do that?” She said, “You spelled my grandmother’s name wrong in the obituary today, and now I can’t put it under the glass on her dresser.” I felt terrible. I said, “I’ll write it again next week, with the spelling correct.” It taught me, you know, you have to sweat the small stuff as well as the big stuff.

CJR So, Caroline, growing up as a kid, did you hear a lot of North Dakota stories from your dad? Did you have a mental image of what North Dakota must have been like?

CG I just think it had this drab color and a lot of snow. I guess being kind of cold and bitter was the picture I had in my mind. I didn’t have a clear sense of what life was like for my dad out here.

CJR You grew up around New York City?

CG Some combination of Brooklyn, Manhattan, Westchester, New Jersey. Definitely a city girl. I went to a city prep school, ran around with friends in Manhattan. Pretty different from North Dakota.

CJR And how central was your dad’s work growing up, in terms of how curious were you about what he did and what that life was like?

CG I think I was interested, but my dad could be pretty private about what was going on at work. Journalism was never a career I considered.

I really wanted to be a historian. I was interested in European history during high school and thought I would go on with some kind of PhD program. I think I wrote one article for my high school paper and it was a Q&A with my favorite teacher.

CJR And where did you go to college?

CG I went to Stanford, as well.

CJR Ah, we have a pattern.

CG There are a lot of coincidences in our story. We both studied the humanities, too.

CJR So you graduated from Stanford with a degree in philosophy in 2014. Then what did you do?

CG I was looking for jobs in criminal justice. I had worked at some district attorneys’ offices and at the Justice Department and I was interested in working on criminal justice reform. And that was how I ended up at The Marshall Project. My dad had heard about this cool new criminal justice nonprofit that was starting. They hired me to be on the business side of the organization. While I was there, I thought that what everyone else was doing seemed way more fun. I wanted to be doing what they were doing.

CJR So then how did you go from there to North Dakota?

CG My co-workers let me, on the side, do some reporting, develop a few clips so I could go out try to find a daily newspaper job. After several months, I decided I should start applying for jobs and found myself out here in North Dakota.

CJR How did you find this job in Bismarck?

CG Journalismjobs.com. Literally, I was just scrolling through. I preferred a cops job or a courts job. I saw this one and North Dakota probably resonated more than some other states I’d never visited.

CJR So, Bill, what was your reaction when you heard that this job had surfaced?

BG I remember when she was working at The Marshall Project and she and I had lunch one day, and I could tell it was one of those lunches where you can tell there’s something on your kid’s mind, but they won’t quite come out with it. Then finally it’s like, “Dad, there’s something I have to tell you.” I was like, “Uh oh.” And it was, “I want to be a newspaper reporter.”

CJR Caroline, why were you nervous about disclosing this?

CG I think it’s a little embarrassing to tell your parents that, actually, you want to do exactly what they do. I felt kind of vulnerable in telling him that.

I was worried he’d think it was a stupid idea. I didn’t have the experience that most reporters do. I didn’t work at the college paper. I didn’t have newsroom internships. This was going to be, in some ways, kind of a fight for me to get that job.

CJR Did you have a sense of the extent of your father’s career and was that what made you nervous?

CG It did make me want to leave town. I wanted to start my career on my own terms and not be known as “the daughter of. . .” with people asking, “did you get this job because of. . .”

BG I’m very proud of her, and I also know she’s a very independent person. I felt good about the fact that she had come to the decision on her own, that at no point had I said, ‘Caroline, this is what you ought to be doing with your life.’

CJR What about when you learned where it was?

BG I had to laugh a little bit because of the way life works.

CJR And when you got there, how different was it from your mind’s-eye view of this barren place?

CG Before taking the job, I sat down with my editor in New York and we started Googling Bismarck. The first pictures that came up were of Otto von Bismarck, not even of the place. And then we kept coming across photos that we thought maybe were Bismarck but turned out to be St. Louis or Cincinnati.

So when I got here, it was way better than I’d expected. It has this cute downtown, historic buildings and an old train depot. And if you go down to the river, there’s just beautiful parks by the Missouri and bridges spanning it.

CJR You left The Marshall Project because you felt reporting sounded cooler than what you were doing at the time. And now you’re in a very traditional, local reporting job. Is it what you thought it would be?

CG It’s really, in terms of local reporting, exactly what I wanted. I start the day at the police station. I cover a lot of local crime. Even just today I was covering a house explosion and visiting with neighbors. I love knowing that I’m very close to the people I write for.

CJR Have you had your equivalent of the woman-punching-you-in-the-back story?

CG Oh, God. I have the internet equivalent. People take the punch in the back on Facebook, writing about me when they think that I have not been sensitive enough. Or, they think that I’ve been biased.

BG I see the way Caroline gets trolled online. Part of it is because the Standing Rock protests are so divisive. You’re either on one side or you’re on the other.

The Bismarck Tribune is very much a straight-up, objective newspaper that’s trying to tell the story from both sides–and that’s not what a lot of people want to hear. I’ve seen Caroline personally targeted on a lot of social media.

CJR Caroline, where do you think this is going to lead you?

CG I would love to stay in newspapers for at least another few years. It feels local and personal. People want to know exactly which church someone belongs to, which small town in North Dakota they’re from. It’s a place where details like that matter, because people actually know the people you’re writing about. I love that. And I want to stay with that somehow.

CJR After the election, there was a lot of talk about how the press missed the Trump constituency and that one of the reasons behind that was that local news infrastructure had been decimated and there just weren’t the people around to hear and understand the sentiments out there. Do you agree with that assessment?

CG Absolutely, especially being in Bismarck where, I want to say, two out of every three people voted for Trump. Republicans have control of the state house as well as two of the three members of the congressional delegation.

CJR But you feel you have an understanding of this Trump electorate in a way that you probably wouldn’t if you lived in, say, New York?

CG Oh, absolutely. I mean, getting to know people who have guns was even something new to me. I honestly didn’t know anyone who owned a gun in New York. I didn’t understand the concerns of people who lived on farms and on ranches.

I read a lot of national news stories right now and realize that they make arguments that wouldn’t make a lot of sense for most people here. It wouldn’t be relatable.

CJR Bill, you read her work obsessively.

BG I’ll confess I have a bookmark on my browser to search for her stories. Part of it is, the Standing Rock story is just incredible. So I’m personally interested in it.

CJR Do you ever offer Monday-morning quarterbacking?

BG I think I’ve been pretty good about that.

CG I call in occasionally when I feel like I’ve got something very sensitive. I trust my dad’s judgment.

CJR Is the fact that you know he’s reading so carefully in the back of your mind when you’re sitting down and typing?

CG It is a little bit of a safety net knowing that my dad is going to read it. It’s really flattering, but it also it’s just nice to know that someone’s going to follow you along so closely. Covering the Standing Rock protest has been one of the most challenging things I’ve ever done, especially trying to balance the perspectives of people. If I don’t get both sides of the story, I’ll come in the next day to four angry voicemails and twelve furious emails. It’s just been nice to know that he’s reading and that he supports me and the efforts that I’ve been making.

BG It’s also interesting being here at the journalism school and dealing with young people in similar stages of their careers. I see these people who are committed to staying here in New York City, or who will only be happy if they get a job at The Wall Street Journal. Caroline went to Bismarck and ended up having a national story. But you could say that about lots of cities and towns around the country. It’s a cautionary tale for a lot of people’s careers.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.