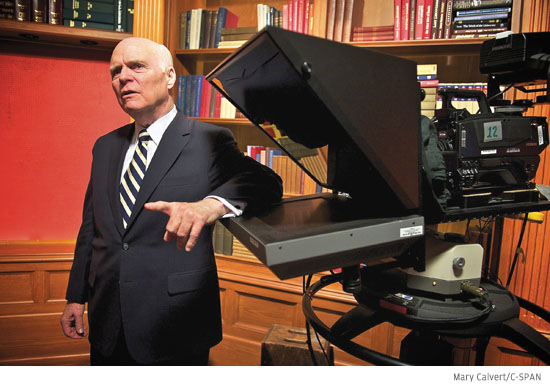

In 1979, Brian Lamb, then the head of Cablevision’s DC bureau, achieved what now seems unimaginable: He convinced Congress and cable executives to back his plan to create a nonprofit that would broadcast the proceedings of the House of Representatives, gavel to gavel. It was called C-SPAN, or the Cable Satellite Public Affairs Network, and 34 years later, it has grown to include three channels and a radio presence, and has become America’s most reliably nonpartisan media outlet. (It also provides reliably good fodder for Saturday Night Live skits.) CJR’s Erika Fry spoke to Lamb in early April, just after he stepped down as C-SPAN’s CEO; he will continue to serve as executive chairman and to host the program Q&A.

Why stop now?

I had been planning it for a couple of years. Susan Swain and Rob Kennedy, who took over as joint-CEOs, were running the show anyway—it was time for them to have the title that comes with the responsibility and authority. And I just turned 70. I feel very good about the timing.

Tell us about the beginning.

I had started talking to people as early as the late ’60s and gotten a lot of blank stares. Their reaction was, “We’ve got three networks, why do we need any more?” The delivery costs of transmitting a signal from New York to Washington to the rest of the country were exorbitant, so no one could get in unless they had a lot of money. When satellite transmission began in the mid-’70s, the costs came down, and people who were interested in creating new programming for television could dream about it.

You launched and sustained C-SPAN entirely with funding from the cable industry. How did you manage that?

Bob Rosencrans, the owner of the Madison Square Garden Sports Network, was the first one to say, “I like the idea, and I’ll write you the check for $25,000 to make it happen.” The cable industry had so much respect for him, and that, probably more than any other reason, was why we were able to succeed—they trusted him, not me.

What’s C-SPAN’s role today?

We haven’t changed people’s lives so much as the multiplicity of channels has. People don’t have to watch anything they watched in the past. People have genuine choice. A lot of people consider what we do to be boring. The only problem with that is that the boring part of your government makes decisions that cost you lots of money. You may not pay attention, but if you ever want to know more, we’re there.

Who watches C-SPAN?

It has never been a huge audience grabber. C-SPAN appeals to the kind of person who is interested in going in-depth.

What do you make of the partisan nature of the current media landscape?

The beauty of cable is that you’ve got choice all over the place. We’re having to relearn as a society how to deal with information. The burden is on us as individuals; it used to be all on the news organizations.

In terms of news and information, is there anything left to innovate?

Time. We need more time. And we need more people who are interested in what’s available to them. The percentage of people that pay attention is quite small—unfortunately we haven’t been able to change that much.

You recently started teaching a course on media and politics at your alma mater, Purdue. What do you hope to impart to your students?

The concept of “follow the money.” You ought to know who is paying the bills for every media institution you use. Then you can get some sense of why a media institution is doing what it’s doing.

Erika Fry is a former assistant editor at CJR.