The Washington Post does a good job highlighting a detail that usually gets glossed over in coverage of the unemployment crisis: those who’ve been without work for 99 weeks or more simply aren’t going to get any more unemployment insurance.

It’s a fact that’s easy to lose sight of in all the he-said, she-said coverage of Congress and its failure to extend unemployment benefits. Even this long AP analysis, “How 2 million lost jobless benefits,”—about the erratic way that unemployment insurance has been extended, and then lapsed—doesn’t deal with the 99ers.

The ins and outs of the unemployment system are a tiny bit tricky; the total number of weeks that someone can collect benefits depends on the unemployment rate in their state and state laws where they worked. (The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has a good primer here.)

As the Post explains, “Since the recession began in December 2007, lawmakers have passed several extensions that stretched the normal 26-week limit for unemployment benefits to as long as 99 weeks in the hardest-hit states.”

But when members of Congress talk about extending unemployment benefits, they’re talking about keeping those extensions in place, not about allowing anyone to collect more than 99 weeks in state and federal benefits.

The Huffington Post’s Arthur Delaney made this point well back in May, but it certainly bears repeating now:

This bill isn’t for the ‘99ers’ and there’s no proposal on deck to give them additional weeks of benefits.

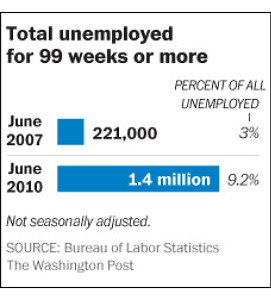

In usual times, those who have been unemployed that long make up a small fraction of the unemployment picture. But these aren’t usual times, and the 99ers have become a big part of the story, as this Post graph shows:

Yup, you’re seeing that right. A whopping 1.4 million people who have been unemployed for at least 99 weeks, or 9.2% of all unemployed. As the story explains:

The 99ers are glaring examples of the nation’s most serious bout of long-term joblessness since the Great Depression. Nearly 46 percent of the country’s 14.6 million unemployed people have been out of work for more than six months, and forecasters project that the situation will not improve anytime soon. Currently, the Labor Department says there are nearly five unemployed people for every job opening.

The Post spoke with a couple of 99ers, including a former construction worker who also spent time working on oil rigs on the California coast and in the Gulf of Mexico. “He also was a bounty hunter,” the paper tells its readers. Oh really? Does that come with health insurance?

In any case, that was then. Now:

Frazee, 50, has applied for work at more places than he can remember since he lost his construction job two years ago. He has tried car dealerships, Kmart, Home Depot and the funky shops on the boardwalk in Seaside Heights, near Toms River. He looked into becoming a commercial crabber, working in title insurance and as a bail bondsman. But no dice.

While searching for work, he lived on $585 a week in unemployment payments. But the checks were cut off in May when he reached 99 weeks. Now Frazee, who is married and has a 5-year-old daughter, is in a financial free fall with no safety net.

“My life has been total stress. I sleep maybe four hours a night, worrying about money,” he said. “I understood the president and Congress had to stabilize the banks, get Wall Street going. I figured something would be done for middle-class Americans, that they couldn’t abandon us. But I was wrong.”

Despite all that good, on-the-ground reporting in New Jersey, the Post gets a little careless closer to home:

Congress’s inaction has been accompanied by a growing sentiment among lawmakers that long-term unemployment benefits create a disincentive for the jobless to find work.

“Workers are less likely to look for work, or accept less-than-ideal jobs, as long as they are protected from the full consequences of being unemployed,” said Michael D. Tanner, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. “That is not to say that anyone is getting rich off unemployment, or that unemployed people are lazy. But it is simple human nature that people are a little less motivated as long as a check is coming in.”

There’s a quick rebuttal from Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney (D-N.Y.), who cites a recent study and declares that benefits “do not inhibit job seekers from vigorously looking for or accepting work.”

But that she-said hardly takes care of it.

As Dean Baker points out, that first part is just some doe-eyed attempt at analysis:

How does the Post know what sentiments members of Congress have? Furthermore is there any reason to believe that their sentiments explain their votes on important issues?

There’s also, as we’ve said before, the flimsy economics behind the claim that the existence of unemployment insurance discourages people from looking for work.

Here’s what the Post had to say on this very question back in March:

Although the availability of long-term unemployment benefits “could dampen people’s efforts to look for work,” the Congressional Budget Office said in a February report, that concern “is less of a factor when employment opportunities are expected to be limited for some time.”

Well, employment opportunities have certainly been limited, and they’re expected to be that way for some time. Hopefully the Post can point this all out, the next time someone tries to make that argument.

In the meantime, good job in pointing to the plight of the 99ers.

Holly Yeager is CJR’s Peterson Fellow, covering fiscal and economic policy. She is based in Washington and reachable at holly.yeager@gmail.com.