“Food Prices Are Soaring and Washington Doesn’t Care,” screeches conservative site The Federalist. The New York Post blares, “Meat, poultry, and fish prices spike to all-time high.” CNNMoney declares, “Soaring prices make it hard to be a foodie.” Even anti-vax quack site Natural News joined in with “Ground beef prices hit all-time high in US.”

Then there’s The Wall Street Journal, ever looking out for the well-to-do, with “High Food Prices Lead to Trade-offs Even in Upper-Income Households,” which relates the story of a dog-spa owner who’s substituting heirloom tomatoes and fresh mozzarella for shrimp at her annual feast for 200 this year. And there was the spate of “BBQ Indexes” around the Fourth of July that said food prices were “exploding.”

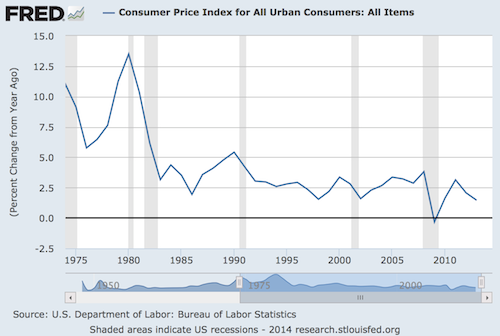

You might get the impression from this cacophony of coverage that inflation is going crazy. But it’s not. When you look at the numbers and not the headlines, you learn that inflation is actually at very low levels, up 2 percent in the last year.

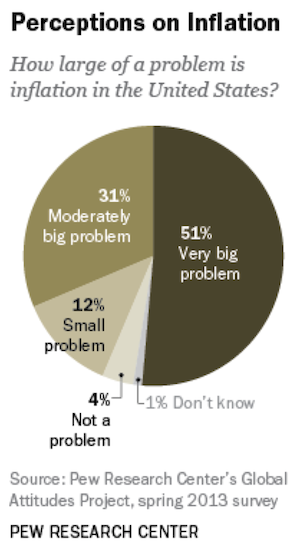

Food inflation, like overall inflation, is low, up 2.5 percent in the past year. But most of us have no idea that’s the case:

Food prices are volatile, which means the press can get lots of easy stories about “soaring” prices when they’re on the uptick (falling prices don’t command as much attention). But they tend revert to overall price trends, context that is almost always left out of these pieces.

People are notoriously bad at knowing what prices are doing. In 2001, the Cleveland Federal Reserve found that respondents thought prices had gone up 6 percent a year in recent years, when they were actually up less than half that. All demographics significantly overestimated inflation, but the most striking disparity in misjudgments was by income group. The poorer you were, the more you overestimated inflation.

That happens to be politically convenient for the very wealthy, who own the vast majority of the assets in the economy. Every asset is a debt debt is an asset on the other side of the balance sheet, and those debts are disproportionately held by the poor and middle classes. Policies that lead to somewhat higher inflation levels make debt easier to pay off (reducing the holding value of assets). Very low inflation or outright deflation makes it harder. In the aftermath of a crisis caused by the inability to service massive amounts of debt, low inflation is a very bad thing for the economy as a whole. See the Eurozone, which is very close to tipping into deflation.

Much inflation overestimation is due to cognitive biases that have nothing to do with the press. Price increases make more of an impression on us than price decreases do, something known as loss aversion. We also pay more attention to price increases in cheap stuff like food that we buy all the time than on more expensive things like clothes or computers that we buy less often. Research in the European Economic Review found that “perceived inflation tends to be higher during periods in which prices of frequently purchased goods (e.g. basic food products like milk and vegetables) experienced larger increases” and that “perceptions are in general not rational, average perceptions of inflation are too high.”

Media coverage exacerbates the problem, in part because, well, journalists are people too–and ones that aren’t necessarily any better with numbers–but also because of the natural journalistic tendency to search for the exception, to play up a “record” this or a “for the first time” that. This CNNMoney segment is a particularly cringeworthy example of that:

A key point to remember when covering prices is that the inflation rate is an average of the retail price changes of many, many different items. No kidding, you say. But this is an important point. It’s the difference between anecdotal evidence and statistical evidence, and lots of people who ought to know better don’t.

All you have to do to get a “prices soaring” story is to select certain items that are up big (there’s always something up big: food prices are volatile) and have them represent “food prices” as a whole. Hamburger meat is up 10 percent from last year, but bread, for instance, is down 0.3 percent. Coffee is off 1.5 percent and vegetables are 0.5 percent cheaper.

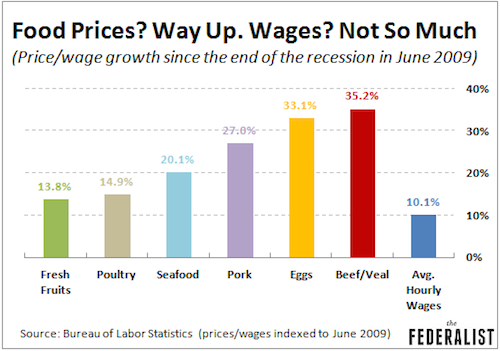

Ben Domenech, the conservative author (one hopes!) who wrote the Federalist post above, gives us a classic example of this misdirection with “Food Prices Are Soaring and Washington Doesn’t Care.” Here’s his misleading chart:

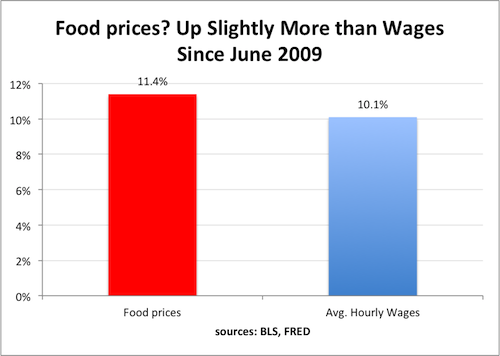

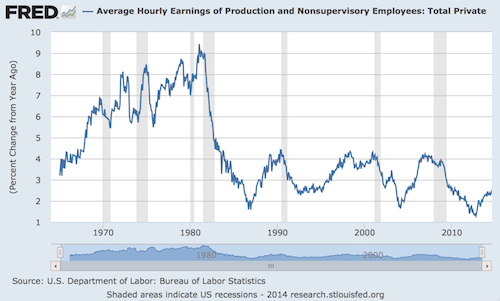

And here’s what his chart looks like when you compare wage growth with actual overall food prices:

This cherry-picking isn’t limited to bloggers. Here’s Stephen Moore, formerly of the Wall Street Journal editorial board:

Nobody believes the statistics out of Washington and often for good reasons. A 2% inflation rate. Ha. Most Americans see the rate of price increases for the things they have to buy – milk, bread, vegetables, medicines, health insurance premiums, college tuitions, gas at the pump – rising at sometimes two to three times faster than the official CPI.

Moore is chief economist at the Heritage Foundation.

The issues with news coverage are typically less glaring, but are still problematic. The New York Post and CNSNews.com both say that hamburger meat prices are at a record high. That’s just not true. In 1980, for instance, a pound of ground chuck cost $1.86 in real terms. It costs $3.92 today. A pound of choice round steak cost $8.12 back then in real terms. It’s $5.58 today.

Then there’s this Wall Street Journal story, “High Food Prices Lead to Trade-offs Even in Upper-Income Households.” The WSJ reports, “Rising prices have been battering the budgets of low-income consumers in recent years. Now, researchers say more high-income households, defined as those earning more than $100,000 a year, report feeling pressure, too.”

But the WSJ is confusing the cost of living with the standard of living. The cost of living has been rising at rates well below historical levels in recent years.

The standard of living is what the WSJ should be concerned about. Wage gains at the bottom and in the middle have been so low that they’re not keeping up with very low price increases.

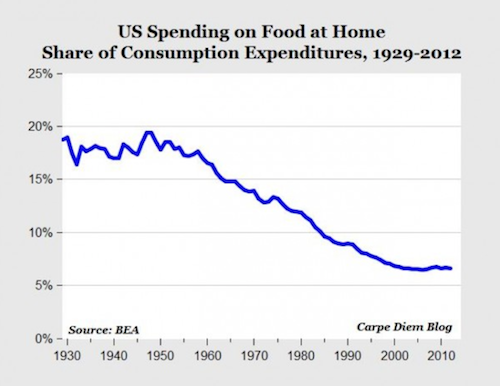

But food expenditures now account for less than 7 percent of consumer spending, half the level of 40 years ago.

This misreporting matters more than you might think. The inflation question isn’t just a simple matter of whether prices are rising. It goes to core arguments about the economy, who holds power, and where policy should go.

Ryan Chittum is a former Wall Street Journal reporter, and deputy editor of The Audit, CJR’s business section. If you see notable business journalism, give him a heads-up at rc2538@columbia.edu. Follow him on Twitter at @ryanchittum.