To read or print a PDF of this report, click here.

Executive Summary

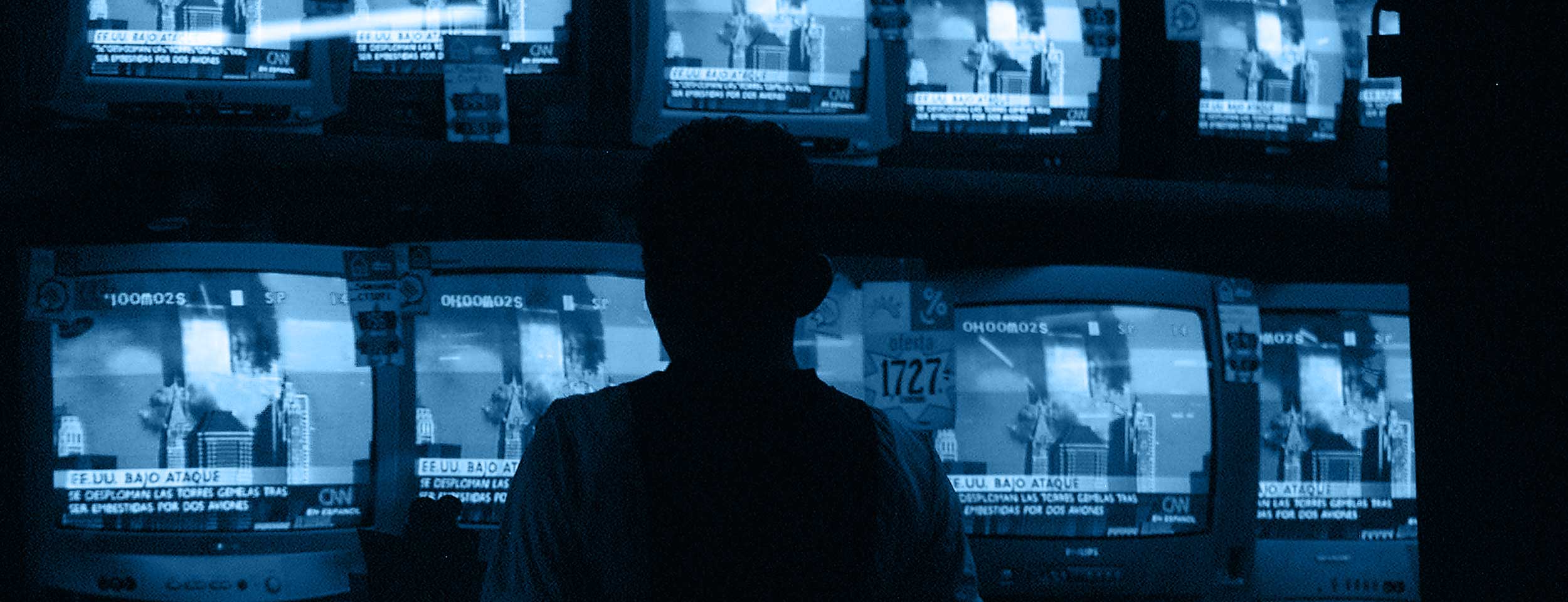

Terrorism is a brutal and violent practice, but it is also a media phenomenon. Terror is vital news: a dramatic, important story that the public needs to know about and understand. But terrorism also relies on such publicity to disrupt society, provoke fear, and demonstrate power. This problematic relationship predates digital technology. In 1999, American historian Walter Laqueur wrote:

It has been said that journalists are terrorists’ best friends, because they are willing to give terrorist operations maximum exposure. This is not to say that journalists as a group are sympathetic to terrorists, although it may appear so. It simply means that violence is news, whereas peace and harmony are not. The terrorists need the media, and the media find in terrorism all the ingredients of an exciting story.1

So what is the responsibility of journalists, who supply the oxygen of publicity? Journalism that reports, analyzes, and comments upon terror faces a challenge in creating narratives that are accurate, intelligible, and socially responsible. Many of the issues journalists face also relate to wider journalism practices, especially around breaking news and conflict journalism.2

In the last few years, this problem has become more acute and more complicated technically, practically, and ethically with the acceleration of the news cycle and the advent of social media. News events are amplified by social media, which often host the “first draft” of terror coverage. These platforms are specifically targeted by terrorists and referenced by journalists. Yet these companies often have only a short history of dealing with the political and commercial pressures many newsrooms have lived with for decades. The fear is that reporting of terror is becoming too sensationalist and simplistic in the digitally driven rush and that the role of professional journalism has been constrained and diminished. In February 2016, when the White House sought help to counterterror groups, it invited executives from Facebook, Google, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, Tumblr, and Microsoft to come up with ideas to halt the use of the internet by extremists.

This paper seeks to describe this developing situation in the context of changes in the very nature of journalism and news. It identifies trends, problems, and best practices for more constructive journalism about terror. In the first section, the paper will look at the problems facing journalism around terrorism: the increasing speed of the news cycle; new technologies and the limits on resources; the challenge of verification, definition, proportionality; and dealing with spin and propaganda.

The second section explores ways towards better reporting of terror: which systems should be in place; what language journalists should use; how journalists should judge perspective and give context in a fast-moving incident; the responsibilities of the journalist to show empathy, to demonstrate discretion, and to avoid sensationalism; and the possibility of creating narratives that show the relevance of what is happening to different communities and influence policy.

The third section will look at the role of the major platforms, especially Google, Facebook, and Twitter. What impact do they have on audiences? How do they relate to the creation of journalism about terror, especially in disseminating news? Social platforms have become part of the way the public understands and responds to terror events, but their ethical, social, and editorial responsibilities are yet to be determined. The role of the platforms is evolving significantly as they become part of the news flow. How transparent should they be about their algorithms or policies that shape the flow of content? New developments, such as live video, are creating fresh dilemmas.

Journalism has a responsibility to help society cope with the threat, reality, and consequences of terrorism. The role of independent, critical, and trustworthy journalism has never been more important. Yet, the news media has never been under such pressure economically and politically. This paper seeks to add to that pressure with a plea for better reporting. This is not just a moral or academic appeal. Unless journalism responds to the challenges that issues like terror pose, it will become less and less valued. Improving the work of journalists is central to the news media’s survival as a vital part of a modern, democratic society.

This is neither a handbook for journalism about terrorism nor a comprehensive research study. The aim of this paper is to provoke reflection and improve the diversity and quality of journalism. This paper also has a self-conscious bias towards American and European media, partly because of the importance of this issue in the current American and European electoral cycles.

Key Findings

- There is widespread concern that the news media is reporting terror events in a way that can spread fear and confusion. Journalists struggle with the accelerating pace of the news cycle and the complicated and diverse nature of terrorism itself. Especially in the context of breaking news, they have to adapt to the speed and complexity of information flows that are increasingly influenced by the authorities, the digital platforms, and even the terrorists themselves.

- There is a danger that news coverage can provide the publicity the terrorist seeks, as well as add to disinformation through poor verification and lack of context. Such publicity can even be seen to be helping terrorists increase their impact and make their recruitment more effective. The way journalists frame news around terror events can also reinforce prejudices and stereotypes.

- Social media amplifies the communicative scale and impact of terrorism, and it adds to the misinformation and emotional responses to terror events. Journalists using social media as a platform or a source do not always maintain the best editorial standards. Social media has changed the very nature of news around terror, for example, by providing imagery, eyewitness accounts, and live video. But it can also deceive, distort, and distract. Journalists are adapting to this new context, but there are still practical and policy problems in terms of verification and news judgment.

- Digital platforms are now where many people consume news about terrorism. They are influential in filtering information and shaping the flow of news, but they do not have the same ethos or practical capacity and experience as news organizations. They also have not yet come to fully understand their role or accepted their responsibilities in the mediation of terrorism, and are still negotiating their relationship with news media.

- Digital platforms have a special dilemma as open environments that also seek to protect their users from offense. While they provide an immense opportunity for journalists and the public to be better informed and to interact around these events, their algorithms and editing policies are still problematic.

Recommendations

- News media organizations need to have detailed guidelines on all aspects of terrorism coverage. They need to deal with language, significance, and context, as well as accuracy and balance. Coverage needs to be backed up by a self-conscious iterative process that allows journalists to reflect, discuss problems and best practices, and improve. Especially for those organizations that are larger or are multiplatform, these guidelines need to be communicated widely. Coordinated internal systems, including systems such as Slack, should be put in place to make sure best practices are maintained even in breaking news or developing story situations.

- Journalists need to be as transparent as possible with the audience about their sources and the limits of their knowledge. Transparency is key to trust. Social media can be a valid and important source, but it must be verified and put into context.

- News media and digital platforms need to develop better technical and editorial systems for verification and accuracy. This might include using “honest brokers” or other agencies and experts. Fact-checking needs to be central. The principle of “better right rather than first” has to be enforced across all publications or broadcasts on all platforms. Editorial management has to make sure the pressure to be fast does not threaten the audience’s right to be able to trust what is published.

- Journalists need to think harder about the way they are framing stories. The news media logic that determines how important a story is and what scale of treatment it gets is too often driven by herd mentality or repeated formulae. Journalists need to reflect on whether they treat similar stories in different places proportionally, and whether they include diverse voices and informed comments.

- News media should invest in the great opportunities for deeper reporting presented by new technologies. Not just to report faster and to more people, but to create better context and clarity. Data visualization offers the opportunity for more fact-based reporting, for example. New platforms offer creative ways to engage with different demographics. But ultimately, better journalism is about digging deeper and looking further. More constructive narratives that include empathy, resilience, and positive responses to terror should be created as part of the news coverage itself. The social impact of news coverage should be considered, not just audience numbers and the drama of the event.

- The digital platforms need to work more closely with news organizations to improve the production and distribution of trustworthy information and informed debate around terror events. They need to bring in more journalistic expertise to improve their own verification and filtering systems. They should use more “honest broker” organizations and be more transparent about their own systems. Above all, they need to accept their responsibilities as defacto editors of news about terror.

The Problem With Covering Terrorism

By its very nature, terrorism challenges normal narrative frames and processes. The basic facts themselves are often difficult to establish after a terrorist incident, much less analyze: What happened? Who did it? Why? What is the reaction of the authorities and the public? What policy or political change might it provoke? How can we report it without making it more likely to happen again?

This chapter looks at the challenges of covering terror events. Some of these are new problems, created by technological innovation or economic and political factors. Some are longstanding issues that have become much more complex in the digital environment, making good editorial practices more difficult to carry out.

Historical Coverage of Terrorism

Terrorism is always a relative term, and its application has changed over time. Former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher once labeled Nelson Mandela’s anti-apartheid African National Congress party as a “terrorist” organization before later going on to urge his release. The American extreme left-wing group the Weathermen, founded in 1969, began as an anti-imperialist group that bombed government buildings and ended up as a counter-cultural cult. The nationalist Irish Republican Army (IRA) was highly organized along military lines which Thatcher also described as terrorist, but with whom she initiated negotiations. Hamas has won elections and has a strong social service network but has also carried out attacks, including suicide bombings on civilians. The American government describes Hamas as terrorist, while others such as Turkey are prepared to treat it as a political actor in the Middle East and give it support.

Because of the term’s subjective nature, some people argue terrorism should not be used at all by journalists. But semantics are only part of the problem. For journalists, part of the challenge has always been how to reflect the perspectives of the authorities and public in their own countries. This is only made more complex with international terrorism and transnational media. For example, this year Turkey was subject to a series of attacks by different groups killing civilians. The way those narratives are framed by Western news media has not been consistent, according to Azzam Tamimi, editor in chief of the London-based Arabic channel Al Hiwar:

Whereas the Islamic State [Daesh] is considered a menace, the PKK and its affiliates are seen as legitimate actors or even freedom fighters. Few Western journalists can resist the temptation to take sides on ideological or cultural basis. The inherited fear or hate of Islam and Muslims usually manifests itself.

Terrorism has always had a symbiotic relationship with news media, one that predates the internet. Journalist and terrorism expert Jason Burke points out that those involved in violent struggle soon realized the opportunity provided by the arrival of mass media:

In 1956, the Algerian political activist and revolutionary Ramdane Abane wondered aloud if it was better to kill 10 enemies in a remote gully “when no one will talk of it” or “a single man in Algiers, which will be noted the next day” by audiences in distant countries who could influence policymakers.

As Burke writes, the same technological advances such as communications satellites which created a globalized media also gave opportunities for expanded publicity for terrorism:

In 1972, members of the Palestinian Black September group attacked Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics, the first games to be broadcast live and the first to be the target of a terrorist attack. The cameras inevitably switched their focus from the sports to the ongoing hostage crisis.

The September 11th attacks were, of course, a watershed moment. Observing the attacks unfold in real time was a communal event, shared by tens of millions of people around the world. A report by Annenberg on journalism and terror published two years later recognized the internet had become a significant factor. It points out that the internet allowed the public to “aggregate bits of information” independently and extended “reach” for smaller media organizations. It also notes that “problematic information is now available on non-journalistic sites.”

Al-Qaeda also exemplified the way that terror organizations have become media producers as well as media subjects. Most famously, Osama bin Laden made a series of videos that allowed him to speak through the world’s media. But as Burke has chronicled, from 2005 onwards with the expansion of the internet, the Al-Qaeda network with its widespread, diffuse organization of cells and affiliates prioritized the recording of its activities and the dissemination of its propaganda online. Some of this ended up in mainstream news media, such as the video of the beheading in 2004 of the American contractor Nick Berg in Iraq.

A few years later, the transformative effect of Web 2.0 and the meteoric rise of Facebook, Twitter, and other social networks would utterly reshape that digital context. Although the core editorial concerns of the report would remain, the media landscape in which terror attacks now unfold is on a very different scale.

Terrorism in the age of instant news and social media is a “different beast,” said former BBC Global News Director Richard Sambrook in an interview. He has worked through the last three decades and insists the subject is now more complex:

Twenty years ago reporting terror was simpler. You knew who had done it. A car bomb goes off outside Harrods, and the IRA communicate directly with code words. The police would know. The issues were more straightforward, and you knew who you were dealing with. Now it’s much more complicated. Terrorism is a different beast, and the fact that it is networked or that it is more likely to be indigenous raises a raft of issues.3

ISIS again raises the problem of how journalists define terror events. Acts committed in the name of ISIS don’t always have clear links with the core organization, and claims of responsibility are more tenuous. This amorphous form of terrorism raises the question of what other violent, ideologically motivated attacks on innocent civilians—designed to gain publicity for a cause and to create fear and reaction—fall under the label of terror. The 2016 attack on the gay nightclub in Orlando, the 2015 shootings in San Bernardino, and the 2016 Munich shopping center shooting were all very different kinds of events described as “terrorism” at some point. If we give a name to one incident, why not another?

The Challenging New Context For the Journalist and Audience

Social platforms are increasingly the place where terrorism is reported first. From ISIS beheadings to video from inside the Bataclan Paris nightclub, these sites are a key news player, sometimes shaping coverage.

There has been a fundamental shift, from news media having control over the flow of information to a more distributed set of sources and platforms. The journalist is no longer the primary gatekeeper. Today’s audiences have vastly more immediate and direct access to a greater volume of material and variety of sources online. The public can get information directly from other citizens, the authorities, or even terrorists themselves. The relative ease with which the news media are able to report events quickly and graphically—thanks to digital technology—means that audiences often report they feel overwhelmed and even repulsed by the onslaught of “bad news” events.

Around terror events, live broadcasting, and particularly television, remains the dominant news information source for a majority of the media-consuming public. However, over the last decade, those reports are becoming more reliant on social media. Coverage of the London bombings in 2005 featured grainy mobile phone video of survivors walking away from the wrecked train carriages down underground tunnels. In the wake of that, the BBC set up a user-generated content (UGC) hub specifically to gather and verify content created by citizens for use in its news.4 By the attacks in Mumbai in 2008, journalists were able to find imagery and information from citizen photography sites such as Flickr and the 900 tweets published every minute. Traditional news distribution agencies such as Reuters became clearing houses for UGC. AP appointed its first social media editor in 2012.

In 2016, the first phase of broadcast coverage of the attacks in urban centers such as Paris, Brussels, Munich, and Ankara was dominated by both video and stills harvested from social media. ABC News’s International Managing Editor Jon Williams, who has been making broadcast news for more than 30 years, points out that this is an historical change in the visibility of news events:

Clearly in the 1970s and 80s very often incidents would happen without pictures. In 1996 the only imagery of the IRA Manchester bombing came from CCTV some time after the event. Today there would be any number of people recording that on cellphones and inundating social media with it in real time.5

New technologies also provide opportunities for other kinds of enhanced visual input such as the live Google Map created by one journalist during the Mumbai attacks. The arrival of live video on social networks means that the citizen (as well as the journalist and terrorist) can become a social network broadcaster. As discussed in the second and third sections, this immediate streamed access creates editorial issues for news organizations and ethical problems for the platforms themselves. At the moment, their use around terror incidents is sporadic but becoming more common.

Social media networks also mean terror news intrudes directly into our intimate media sphere. The same profiles we use for personal content or the consumption of entertainment, routine information, and social exchange are now a space filled with dramatic and shocking images and messages. News is increasingly consumed on mobile devices and smartphones, making the news part our personal, socially connected lives. In their interaction with media, it is not surprisingly that people react more personally, emotionally, and instantly than ever before.6

Framing the Narrative: Definitions of “Terrorism”

There is enormous pressure with a major breaking story to come up with a fresh line amidst the surge of information. Audience expectations of instant reportage combined with the increasing market competition add to that need for journalists to work quickly and at the limits of their abilities and resources. This rush to certainty can lead to false leads from mainstream as well as social media. Journalists and audiences inevitably seek to fit terrorist incidents into a pattern. This is exacerbated by group think among journalists, especially on social media. In the race to publish and in the midst of a dangerous situation it is difficult to maintain a critical attitude to those dispensing authoritative information.

One manifestation of this is the expert commentator, who is often chosen as much for their closeness to a TV studio as for their relevant insights. Live broadcasters are developing a language that relativizes its statements: “this is what is being reported,” “this is what we are being told,” “reports on social media suggest.” The danger is the audience does not understand the precise nature of the qualifications involved.

Adding qualifiers such as “appears to be” or “potential” to “terrorism” is highly risky in a breaking news story. “Terrorism” has traditionally been seen as an external threat, such as 9/11, but as the London Bombings of 2005 and many of the incidents of 2016 show, there are “home-grown” terrorists who draw upon international networks as well as “domestic” terrorists with a local or national agenda. Individuals who carry out terror attacks are not necessarily a “lone wolf.” Someone with mental health issues might also be a terrorist. The descriptions are rarely clear. Section two makes the case for greater reflection on terminology and sets out some principles.

One option is to never use the word. Al Jazeera English made it clear that its journalists should not use the term, along with others such as “jihadist.” BBC guidelines do not ban the use of the term, but admit it is problematic:

The word “terrorist” itself can be a barrier rather than an aid to understanding. We should convey to our audience the full consequences of the act by describing what happened. We should use words which specifically describe the perpetrator such as “bomber,” “attacker,” “gunman,” “kidnapper,” “insurgent,” and “militant.” We should not adopt other people’s language as our own; our responsibility is to remain objective and report in ways that enable our audiences to make their own assessments about who is doing what to whom.

This approach has not changed significantly in principle in response to recent developments in terrorism or media technology.

ABC News in America has a similar approach. International Managing Editor Jon Williams says their journalists should not use the word “terrorism” except when quoting other people:

Words matter. We would not have described [the 2016 London Russell Square stabbing] as a “potential terror incident.” We would just describe it as a stabbing and have put it in the context of other incidents. Our modus operandi is to do what it says on the tin. We would wait to see how someone [in authority] characterized it. With the San Bernardino incident our assumption was that with the prevalence of mass shootings in America we should assume it’s just a shooting. It began as a workplace shooting but came into the context of people who had been radicalized but it still requires someone to characterize it as “domestic” terror or “inspired by ISIS.”7

As Sambrook points out, deciding whether to use the word “terror” is only part of the problem:

I think it’s a bit of a cop out to simply say you won’t use the word “terror” or “terrorism.” There are some actions to which that term will apply. I think there is a neat way through this. Simply describe what has happened and report what people have said. Recent incidents have shown how many factors are potentially involved. Is the killer suffering from mental illness, or if he shouts “Alluha Akbar” does that make it a Jihadist? In the end report what has happened and what people say and let the viewer draw their own conclusions 8

Above all, the growth of terrorists ascribing a religious motivation to their actions has raised fresh dangers of associating neutral words such as Islamic or Muslim with terrorism. While the terrorist may make religious claims, there is no reason for journalists to treat that uncritically.

Avoiding Harm: The News Media’s Relationship to Terrorism

Terrorists are now media producers themselves. Anders Breivik was acutely conscious of the role the media would have in promoting his beliefs. He sent a 1,500-word manifesto to more than a thousand people just before his first bomb went off. ISIS has an extensive media production capacity, creating videos and articles that are distributed through highly-developed social media activities. They use the kidnapped British journalist John Cantlie as a subject of their videos and then as a presenter. Much of the material is English-language targeted at potential sympathizers or recruits online internationally. To tell the story of what the terrorist is thinking, saying, and doing it is often useful to use this material. But the danger is that even in a critical context this effectively relays and amplifies the terrorist’s message. As Erica Chenoweth explains:

What’s important is that the imitative effects of mass shootings and terror attacks may not be unrelated to one another. The blurry distinction between what constitutes mass shootings versus acts of terror means that, functionally, those motivated to obtain notoriety or political power through graphic violence may not really care whether their competitors are “terrorists,” “shooters” or something else.

There is always a danger of media giving terrorists details about security operations that help them improve their work. This is particularly relevant in the midst of a terrorist operation. Live video or pictures of a scene may endanger security forces or hamper their work. It is essential that, when the public is at risk, the news media works closely with security officials.

There is also a wider problem that those authorities, especially politicians, frame their commentary on terror events to suit their own interests. Journalists have an obligation to report what powerful people say—but they do not have an obligation to replicate their perspective. As British journalist and former London Times editor Simon Jenkins argues, politicians have their own agendas:

To the media, terrorism is meat and drink. To politicians, it is an opportunity to flex muscles, brandish guns, boast revenge. Talk of war adds ten points to an approval rating. It saved George Bush as it is now saving France’s François Hollande. Counter-terror theory may advise caution and an emphasis on normality. Political necessity counsels the opposite; the trumpets and drums of battle. It requires the terrorist’s deeds to be amplified, headlined, exaggerated to justify a warlike response.

The sheer volume of terror news may make further attacks more likely. Michael Jetter, a professor at the School of Economics and Finance at Universidad EAFIT in Medellín, Colombia argues that increased coverage of terror attacks correlates to an increase in their frequency.9 He also argues that terror tactics that have greater media impact, such as suicide bombings, could lead to their increased popularity. The French political philosopher and expert on the causes of terror Olivier Roy argues that media coverage helps extremist organizations in recruiting and mobilizing terrorists. He says that the framing of terror events by politicians and the media “valorizes the up rootedness of uprooted people” and provides them with a sense of belonging and meaning.

Language is critical because the public make judgments about risk based on the terminology involved. Just because something creates “terror” does not make it a “terrorist” event. This Daily Mail Online headline uses the word “terror’—but the sub-head makes it clear that it was not “terror-related’:

At what point does a “hate crime” such as the Charleston church shooting become categorized as “terrorism”? Breivik had active links with extreme right-wing groups and used his actions to promote his anti-Islamic, anti-liberal ideology. His convictions included “terrorism.” However, in the media, he was most often referred to as a mass murderer or mass killer, not a terrorist. Likewise, Ali Sonboly, the 2016 Munich shooter was described by police as “inspired” by Breivik, but they said the incident was not “terror-related.” Sonboly had been receiving psychiatric treatment, raising the definitional problem around terror and mental health. In considering the mix of motives, it does seem that mainstream media has a propensity to describe events as “terror” if they have some element of jihadist or Islamist ideological ingredient.

Even if a recognized terrorist organization does claim responsibility, journalists may need to fine-tune the language. There was evidence that the 2016 Wurzburg train attacker was “inspired” by ISIS propaganda rather than controlled by them, yet ISIS still claimed it as part of their campaign in Europe. The Ansbach bomber Mohammed Daleel had stronger links to ISIS including a propaganda video he made pledging allegiance to the ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. His preparation for the bombing was more sophisticated and planned. Does that make him more of a terrorist? What significance should journalists have given to the fact that several of this summer’s German attackers were asylum seekers or refugees? As soon as perpetrators are identified with a minority group, the danger is that community will be impugned in a way that does not happen when perpetrators are seen to be from the majority population. In a political environment where in many regions there are tensions over ethnic identity, immigration, and cultural values, it is even more important that the news media does not make unqualified connections between race, religion, and terror acts.

Verification and Transparency

There are some obvious problems created by this new engagement from the audience on terror events. There is a great deal of misleading or false audience-created content, much of it highly reactive and subjective, and there is an increasing number of fake news sites that deliberately spread this content to attract traffic. Social networks are somewhat self-correcting and are moderated, but this can be delayed—by which time falsehoods or false impressions have spread, uncorrected.

A missing student Sunil Tripathi was named on Reddit in the wake of the Boston Marathon bombing in 2013, leading to a manhunt before police were able to rule him out. But in that four-hour period many journalists disseminated the rumor on their own social media accounts. They appeared to accept a lower standard of verification then they would have done for publication on their regular news channels or sites.

The primary function of journalism is still to get facts right. The volume of social media content and the fact that some of it is inaccurate or misleading should not make professional journalists complacent. News media content is now blended into the audience’s news feeds and audiences often do not discriminate between “amateur” and “official” or journalistic content online. Research shows that on social media people trust their peers as much as the news media (although that includes their peers sharing news media content).10

In this context, it is even more important that the news media distinguish itself by providing reliable information. Statistics show mainstream journalists are still trusted to varying degrees, depending to the medium, the user’s age, and the perceived partisanship of the news brand. One of the key variables is their perception of the accuracy and impartiality of the journalism.11 Verification of facts and the correct expression of “what we know to be true” is under enormous pressure as breaking news accelerates.

As discussed in the next section, editorial guidelines at most major news organizations have since been revised to make it clear that the same standards must apply to gathering material from or posting material on social media.

Better Terror Reporting

This chapter will identify how news organizations are best able to address the challenges set out in reporting on terrorism.

Reshaping the Newsroom

New skills are needed to understand user-generated imagery from social networks, terrorist propaganda on specialist websites (often not English language), government or security communications, expert and academic analysis/research blogs and websites, local, specialist, international, and foreign language news media organizations, aggregators, bots and campaign groups.

Yet a guiding philosophy through this complex network of information should be simple: Only report as facts what you know to be true. We can put aside philosophical debates over truth and focus on the journalistic process of identifying some kind of evidence-related process that gives us the best, most reliable account of who, what, where, when, and why.

The newsroom will always be core to this process: its resources, task management, technologies, skills, and infrastructure. Increasingly the larger broadcasters such as CNN and the BBC are the ones that have extensive online operations with the capacity to cope with the full range of sources and platforms. Legacy newspaper operations such as The Guardian and The New York Times have developed processes such as live blogs where they too are able to exploit and showcase a greater number of sources. At the same time, local news organizations have the advantage of intimately knowing their area, and are often able to keep ahead of their larger rivals as news breaks. Other specialist media, such as the nonprofit Conflict News Twitter account, act as aggregators, filtering information online.

Some news organizations such as The Wall Street Journal and the UK’s ITN have outsourced some of their newsgathering to agencies such as Storyful, which have highly developed expertise in verifying imagery, video, messages, and other data from social networks. “Real-time information discovery company” Dataminr specializes in scouring Twitter and its analytics for breaking stories including the first news alert on the death of Osama bin Laden. Banjo has developed software that allows it to monitor geo-located social media activity globally and provide news alerts to its media partners, including American Sinclair Broadcast Group. These companies often have commercial as well as news media clients and they do not claim to be journalism agencies. But they are engines for online discovery that can spot stories before newsrooms.

First Draft News is another coalition of organizations that provides verification insights, training, information, techniques, and research. There are also individual small-scale operations that focus on particular areas or issues, such as Bellingcat which its founder Elliot Higgins describes as “by and for citizen investigative journalists.” It has developed sophisticated forensic data-analysis tools and techniques to provide deeper information in the wake of events. The European Journalism Centre (EJC) has produced a Verification Handbook that gives detailed guidance on how this can work in emergency situations such as terror attacks.

Organizations such as First Draft and the EJC demonstrate the processes that journalists can adopt if they have the time and will to do so. The key is to have a set of guidelines related to breaking news and terror that can form the basis for newsroom culture, standards, and practice. Different news brands will make their own calculations about how to implement best practices universally across an organization. CNN and BuzzFeed use the internal messaging system Slack, for example, to ensure that all staff on all platforms are getting the same guidance as news breaks.

Getting To the Truth

CNN took a serious reputational hit for its mistake in coverage of the Boston Marathon. Like almost all major news organizations, it has adopted a more effective way of reconciling the competing demands from audiences for instant news and verified information. It now has a more coordinated editorial management structure with digital platforms integrated with broadcast.

The business as well as the ethical case for journalism in a media environment so full of false, partial, or provisional information must be based on trust. Citizens now have social media feeds full of messages, often from peers not professionals, that alert them to breaking terror news. When they click onto the mainstream news media material, they expect something more reliable. Journalists cannot police the internet for truth, but as well as getting their own facts right, journalists can also have a role helping to identify fake or mistaken information on social media. This kind of “myth-busting” helps arrests the spread of false information and can educate the audience in online verification.

“Publish and be damned” is not applicable in the terror context. Samantha Barry, CNN’s Head of Social Media, said in an interview that they are aware of changing expectations of the audience, but they sometimes have to pause before publication to retain trust:

It is really important for CNN to be right not necessarily first. Audiences are more forgiving than other media people when it’s a developing story. There was one example from the Dallas police shooting when police released a video of a suspect. We didn’t put it out on digital and social because we saw questions about whether it was a suspect. The police then rowed back. We get pressure for example, from people tweeting at us when they see something on social media. This happened around the recent evacuation of JFK airport. But we only put out the story when we had something we were comfortable with what we knew for ourselves.12

Newsgathering from social media should abide by the same principles used for any other source. However, the BBC gives additional advice in its guidelines on gathering user-generated content around issues such as copyright, crediting producers, and treating the public with respect and sensitivity. Organizations such as First Draft News also have more detailed advice on verification and the treatment of contributors.

Transparency In Breaking News

News organizations will make individual mistakes of fact, taste, or framing, but it is how you handle the development of breaking news overall that matters. News organizations are desperate for audience attention. Online analytics now provide instant, live statistics on page views, engagement, and traffic, as well as the usual broadcast audience levels and share. Competition is a vital motive for journalism, and especially during breaking news, it drives newsrooms to provide a rapid response as well as more considered context. So increasingly news organizations must develop a credible grammar for provisional narratives. Donald Rumsfeld’s famous aphorism is relevant here:

There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

Mainly through social media, but sometimes through other news media sources, the audience is now often conscious of the basic facts and “known unknowns” as news breaks, whether via social or traditional media. As Sambrook points out, social media tells people instantly that something has happened, but it cannot always explain what it is:

You get a situation like in Bangkok [2015] where we first know that something has happened because people start tweeting and then a bystander starts broadcasting pictures of the aftermath on live on Periscope [Twitter’s live stream tool]. The guy doing it literally didn’t know what he was showing and when he realized he was filming body parts he regretted it.13

As that amateur broadcast went out, viewers were able to comment and the man filming also responded, but while his actions gave the world images of this event, it could not give much insight.

This is now how news is made. There has been some kind of explosion. But we do not know what kind of explosion. One possibility at the front of people’s minds, regardless of statistical probability, is terrorism. But journalism’s key task is to find out what we don’t know.

Journalists covering breaking terror news are adapting their language and being humbler in publicly sharing their ignorance as well as their knowledge—something once unimaginable to newsroom culture. To say that something has not been confirmed is not adequate as a final narrative, but in the early stages of an incident it is as important to identify uncertain information. Authority is enhanced, not diminished, by making sources as clear and precise as possible. A general statement such as “reports on social media” is at the worse vague end of the spectrum, but if the platform and social media account is identified then that helps build a more nuanced picture. This is part of building much-needed media literacy in the audience. Detailed, continual transparency helps promote public understanding of the process of news as well as building trust in its outputs.

News organizations need to be aware that simply by reporting an emerging situation they are signaling that it is of potential significance. “We are getting reports” is not a phrase that should allow editors to suspend their usual judgment. That judgment, though, can now be more openly made.

News media institutions have intellectual and professional capital. It is good to share the caveats and conditions that are applied in the newsroom on screen. With breaking news—especially on a topic so fraught with competing and complex definitions and perspectives as terror—authority is gained not by automatic certainty but by sharing the journey towards understanding.

Using the Right Language

Journalists have to use shortcuts to compress complex realities into formats people can consume quickly. The formula of headlines, edited video, graphics and so on are part of the necessary process of simplification and communication under limited time and space. But with a complex subject like terror, precise language is vital, as Mary Hockaday, the BBC’s controller of World Service English wrote to me in an email:

The recent rapid sequence of events does challenge us about language. Terrorist, the lone wolf, the mentally ill, the loner, ISIS directed, ISIS sympathizer, ISIS inspired…. News events rush past and headlines simplify… but it’s really important we go on striving to be precise, recognize the complexity – of the people and indeed what the policy response needs to be. And use accurate, concrete language when we can rather than generalities.14

Language should be concrete and consistent. In Western media, critics say that with the post-9/11 rise in extreme violence that proclaims itself to have an Islamist motivation, there has been a tendency to reserve the term “terrorism” for only that category:

We used to use terrorist to describe all kinds of people, from Irish Catholic republicans to American Jewish radicals. But since 9/11, we’ve been using it much more swiftly in reference to Islamists. (Adam Ragusea, Slate).

Dylann Roof, the alleged perpetrator of the 2015 Charleston shooting of nine African American churchgoers was accused of a hate crime, not terrorism. Yet he had an ideological agenda and drew upon the ideas of white supremacist groups. Micah Johnson, who shot police officers in Dallas, appeared to have a strong political motive for his actions based on his anger at police shootings of black civilians. The BBC’s Director of Editorial Policy David Jordan warns against applying the term terrorist too widely:

The problem is with the word “terrorist” rather than “terrorism.” When you apply it to an individual you must do it with care and caution. In the case of the Charleston shooter he appeared to have mental health issues and political motives but was not associated with a political group that had the declared aim of using extreme violence against innocent people to achieve a specified goal. As an international news organization we increasingly find governments around the world who want to apply the label “terrorist” to anyone who opposes them and so it is important not to use it without thinking.15

As terrorism becomes more diffuse and the association of a specific act with an organization becomes harder to ascertain it becomes even more important that news organizations compare and contrast the way they use words—not just terrorism itself but also the accompanying adjectives and the assumptions they carry.

Language matters especially when it turns to metaphor. Most famously, the use of the “war on terror” metaphor should act as a warning. Its widespread deployment following the cue from the George W. Bush administration declined as mainstream media understood that actual wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and against ISIS were not working militarily. As one of the UK’s most senior judicial officials, the then Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Ken Macdonald made clear just two years after the London Bombings, the military metaphor also boosts the terrorist’s sense of power and ignores other policy options in countering their campaigns:

London is not a battlefield. Those innocents who were murdered on July 7 2005 were not victims of war. And the men who killed them were not, as in their vanity they claimed on their ludicrous videos, “soldiers.” […] We need to be very clear about this. On the streets of London, there is no such thing as a “war on terror,” just as there can be no such things as “war on drugs.” […] The fight against terrorism on the streets of Britain is not a war. It is the prevention of crime, the enforcement of our laws and the winning of justice for those damaged by their infringement.

Labels such as “lone wolf” or “evil” resonate but have little factual meaning. Apart from sensationalizing the perpetrator, they give the sense that the individual was operating in isolation. In fact, it is difficult to find any examples of terrorists not influenced to some degree by the messaging of terror groups even if their actions were not explicitly controlled or directed.

Likewise, the distinction between mental health and terror is rarely clearcut. On the one hand, the application of the label “mental illness” is a useful indicator if supported by some authoritative assessment that helps guide the audience. The London 2016 Russell Square stabber had been receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital, for example. But it is arguable that anyone who believes in killing innocent people for an ideological cause has a dysfunctional psychology. Mainstream news style guides do not refer to this dilemma specifically. Jordan says this is an area where guidance is still evolving:

The mental health issue regarding terror is a comparatively new problem and we are talking with other standards people to try to create guidelines. But by its nature it is complex. For example, just because someone once had treatment for a mental health problem does not mean that they are still “mentally ill. So as usual, we should avoid vague terms and only report facts.16

Language matters because it conditions the public acceptance, for example, of negotiations with extremist groups as political or military actors.

In the heat of reporting a breaking news incident such as the London Russell Square knife attack, we can see how the news media struggles to cope with these competing demands for categorization as “facts” are emerging. The attacker, Zakaria Bulhan, was arrested immediately after the incident occurred at around 10:30 p.m. on Wednesday August 3, 2016. The story broke quickly, partly through eyewitness accounts on social media. The news media initially reporting it prominently as a “possible” terrorist attack, based on police statements. By 11am the following day, the police were effectively ruling out terror. A random stabbing with one fatality by a person with a mental health problem would have been a story in its own right, but not necessarily the lead on the BBC’s flagship morning radio program Today without the terror connotation. The initial prominence of the story—and its later drop down the running order—is not necessarily a failure of journalism; it reflects the development of the story through time. At 5am as the Today program prepared to air, Assistant Commissioner Mark Rowley, from the Metropolitan Police, said:

This was a tragic incident resulting in the death of one woman and five others being injured. Early indications suggest that mental health was a factor in this horrific attack. However, we are keeping an open mind regarding the motive and terrorism remains one line of inquiry being explored.

As the editor of the BBC’s morning Today program, Jamie Angus, explains how they assessed a series of factors:

With the benefit of hindsight, we would not have given the story such prominence, but at the time it was right to treat it so seriously even though we did not have absolute confirmation that it was terrorism. When the story broke we got in extra people to prepare our morning report because the 1am statement by the police mentioned terror as a factor and they repeated that later. The genre of the attack was not clear, but it often isn’t a clear distinction between someone who is mentally ill or a Jihadist. Of course, radicalized people are often psychologically vulnerable anyway. The police had also mentioned that he was Norwegian with Somali heritage, which suggested they were considering a terror motive, too. We took our cue from the fact that such a senior officer was still mentioning the possibility of terrorism.17

Much of the pressure to publish live is driven by news breaking on social media first from “non-journalistic” sources. As one producer on a news channel says, the fear of missing out on a story surfacing on social media can lead to the temptation to cover it before significant details are confirmed:

I resisted “breaking” news of a shooting in a Spanish supermarket until we knew more. As it turned out, it was a domestic dispute. We didn’t report it at all. But my boss on the day wanted to break it because people were mentioning it on social media and he felt it “might” be something else.18

But the news media is not a tracking system for online activity. Platforms such as Facebook are increasingly a source for news for the public and can provide a great source of facts and opinion but it is highly selective. All the newsrooms spoken to for this report insist that they apply the same editorial standards to social media as to any other source. As the CNN guidelines state:

Citizen-generated reports are subject to the same strict review process that CNN applies to traditional reporting before they are included in CNN stories.

Working With Social Media

The best news media encourages interaction and listens and responds. Alex Thomson, Chief Correspondent for the UK’s Channel 4 News uses his Twitter feed to show and discuss his journalism as he gathers news. He posts smartphone footage and replies to comments. Other “traditional” international correspondents such as CNN’s Christiane Amanpour have used Facebook Live video to provide a more interactive user experience. Journalists say that while much of the feedback can be bland or unhelpful, it can help give a sense of what the public misunderstands and so encourage journalists to address those gaps.

Correspondents such as the BBC’s Matthew Price say even interacting with people who complain or are confused can be a useful way of understanding what people do not know. By correcting or responding to them you can help that individual but, of course, the message also goes out to the journalist’s wider network:

Covering the refugee crisis live from the field in its early phase, I got many comments saying that these were not real refugees because they were almost all men. So they were “just” economic migrants. I reflected on that and asked the refugees where the women and children were. They pointed out that often the men go ahead to prepare the way for their families. So although the images were of men, many were in effect, travelling ahead of their families. I then made sure to make that point on social media but also in my reporting.19

For Price, even a “mistaken” audience comment on social media can lead to better journalism.

Sometimes the public knows more than the journalist about an aspect of a story. They might have eyewitness accounts, local knowledge, or specialist insights. Social media can provide perspectives and information not available through the usual channels or sources and it can provide them quickly. Tapping into the social media of groups traditionally marginalized by mainstream media helps the journalist and the public understand the context of the extremist individuals who might draw upon those cultures. This could be the online discourse of US “alt right” activists or the social media messaging of youths in Molenbeek, the Brussels district with a high Muslim population where ISIS had text messaged locals. There is increasing evidence that those marginalized communities feel misrepresented by mainstream media. Paying attention to their online voice—albeit not always representative—can add to overall understanding for the journalist and audience.

Editors, too, should take the context of social media into account when making judgments around framing narratives. Just because posts on social media are often confused, misleading, or ill-informed does not mean they should be dismissed. This is especially true now that news coverage itself is subject to constant online critique. The Guardian’s social media editor, Martin Belam, said:

And all the time you’ve got people @-messaging you that you are doing it wrong, or serving an agenda, or displaying bias. With one tweet about the Iranian background of one of the recent attackers, the replies criticized The Guardian for being racist to even mention it, and other people criticized The Guardian for trying to suppress information that he was an ISIS fighter.

But these also raise valid points that can contribute to reflection in the newsroom about the framing of terror narratives.

Avoiding Harm, Relations with Authorities

Reporting on terror events must also be sensitive to security considerations. Journalists have a duty to report as fully as possible but in a terror-related scenario the news media has a responsibility to avoid causing harm. Journalists can legitimately not report facts if doing so would increase risks or hamper a security operation. This means responding to requests from the authorities to not report particular facts or not to show certain images. There should always be a due process within the news organization of making that decision. Ideally, the fact of any decision to restrict reporting should be reported.

During the 2004 school siege in Beslan, Chechnya, the BBC decided to go on a time delay for its live feed because of the danger of showing graphic imagery of hostages including children. During the security operation following the 2015 attacks on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris and the siege of a supermarket where hostages had been taken, the French broadcast regulator issued a notice to domestic newsrooms asking them to show “discretion.” Paris police on the scene told TV crews not to broadcast their officers in action. At the same time broadcasters were regulating themselves. Paris-based BFM TV chose not to broadcast the police rescue operation live. It also did not air an audio interview it recorded with the hostage-takers themselves until after the incident was over. BFM TV journalist Ruth Elkrief said it was a series of decisions they had to make for themselves in the newsroom:

It’s very difficult. We have to move fast. But are we undermining the investigation? Are we being manipulated? We’re asking ourselves these questions constantly. We had several emergency meetings during the day to debate what to do. We’re always checking ourselves.

Transparency about making those judgments helps build the understanding and confidence of the audience. Clearly, journalists cannot give a running commentary on all their editorial decisions, but a similar approach could be adopted to that when embedded with the military during conflicts, as suggested in BBC guidelines:

We should normally say if our reports are censored or monitored or if we withhold information, and explain, wherever possible, the rules under which we are operating.

Journalists have a civic duty to cooperate in the interests of public safety, but this does not mean automatically complying with police or security requests. The seizing of the laptop of BBC journalist Secunder Kermani—who had made contacts with extremists—appeared to challenge in principle the idea that journalists can ever talk to terrorists or their associates.

These judgments are hard at a practical level with breaking news. Journalists now have access to real-time live video and images of alleged participants instantly uploaded on social media. The news media should not wait for guidance before assessing whether using material might cause harm. Showing the outside of a building where an incident is taking place might, for example, give the terrorist information about deployment of security forces. Clear lines of communication with the police are vital. As one senior broadcast journalist said, there can be a moment when the natural desire to cover a breaking story clashes with security imperatives:

During recent shootings in Munich, the local police tweeted several requests that everyone refrain from speculation, and also that people stopped showing live pictures of police positions. We were doing exactly that at the time, taking live agency feeds of heavily armed cops, and staying on air by saying things like “we shouldn’t speculate but …20

For local media especially, the relationship with police can be mutually beneficial. During the Lindt Cafe siege, Channel Seven had remarkable access to police operations because they agreed to give them oversight of their picture feeds. The police were able to use the material to assess what was happening. The broadcasters in turn had to agree not to show sensitive images live, to have a time delay on their broadcast feed, and to keep some material back until the siege was over.

Not Helping the Terrorist

There is also a long-term issue about how detailed media coverage might help terrorists improve their operational effectiveness. As Javier Delgado Rivera has written, thanks to news media reports, terrorists now know how the FBI tracked the network of the San Bernardino shooters with information from their damaged cell phones. They know that French police linked one of the Paris attackers to the Brussels attacks through parking tickets. Perhaps future terrorists will be more careful:

Detailed media reporting on police investigations can inadvertently help attackers avoid past miscalculations and refine their modus operandi. Journalists would argue that their job is to protect society’s right to know. Yet in such exceptional circumstances, editors should ensure that the latest information they feed to their audience is useless to fundamentalists seeking to do harm.

This is especially important as terrorists become increasingly self-radicalized and train themselves partly through the study of previous incidents. Overall, it would be impossible for the news media not to report any circumstantial detail that could help a future terrorist, but as with the reporting of suicide, where journalists refrain from describing methods of self-killing, discretion around the depth of information on methods and countermeasures is possible.

This is part of the bigger issue about proportionality around reporting on terror, according to University of Western Australia Professor Michael Jetter:

The purpose of not reporting suicides fully is to not encourage copycats. What German newspapers are doing is they’re blowing it up so much that everybody who is seeking attention is really given the signal that, “I will be famous.” That is very likely a reason why you see so many more of those things. It’s a scary development and I do think they need to think about how they cover things.

As we have seen there are many reasons that journalists might decide to withhold facts or material. This can vary due to the news brand’s ethos and their audience culture. British broadcasters now rarely show ISIS propaganda videos, although there is no blanket ban. But when ISIS made a video of a four-year-old British child apparently blowing up a car with captives inside, the Sun newspaper ran the image as its front page: “Junior Jihadi” and the New York Post even ran the story with a slide show of “terrorist photos that made us gag.” The coverage was clearly hostile, but it was the kind of publicity ISIS sought. A few months later ISIS released videos showing children executing prisoners. The BBC’s Jordan said they chose not to show the images partly because of the issue of consent with a minor, but also because they did not want to help ISIS:

It was perfectly possible to tell that story without using the pictures. The danger is that by showing it there becomes a kind of diminishing return for the terrorist so the next time they have to create something even more outrageous. Arguably, if people had not published those images in the first instance then ISIS would not have made more. This is partly why we don’t show propaganda videos unless there is a serious news reason to do so.21

The counter argument is that to understand the full horror of terrorism, it is vital to show what they do in full detail. Yet, in a world where just about everything is available online it is difficult to argue that the public is being denied information. In the end, it is a decision that should be thought through by the individual organizations in relation to specific events.

By reporting on a terror event, research suggests that we make another one more likely.22 So it is important that the scale of reporting as well as its content is considered. The drama and danger combined with the ideological threat and human impact create a compelling narrative cocktail. For The Guardian, the 2015 Paris attacks saw more unique visits to its website than any event in its history bar one—the extraordinary story of Britain voting to leave the European Union. The increasing proximity of terror attacks to our everyday lives adds to their fascination and immediacy. The prominence given in terms of duration and visibility of reporting on terrorism sends a strong signal to the audience. Judgment on this is not a science, but journalists need to consider external perspectives as well as the temptation of “going big” on a particular incident.

Geographical Bias

There was a lively debate in the wake of the Paris and Brussels attacks comparing the coverage of those incidents with similar incidents in places like Beirut and Ankara. These events were reported in the Western media but not to the same extent. Journalists explained that many of the complaints on social media about this were inaccurate and suggested critics were trying to score political points and demonstrate their own ethical virtue. Journalists point out that even when reported, the coverage attracted far less interest from the public. This is partly because overall audiences will always respond more to news that has relevance to their own lives and for a Western audience, the French and Belgian attacks were on people and a society that the majority population could identify with more readily. ABC’s Jon Williams explains:

Our first responsibility is to the audience, and we have a US audience. For them a bomb in Paris is a bigger deal than Baghdad. They visit Paris, they know and care more about France. That’s not to say we don’t cover the Iraq incident but we will generally tell stories that connect with our audience. In the same way an earthquake in Italy is more important than the same deaths in Sumatra because these places speak to Americans in a way that others don’t. It’s different if you are a global broadcaster is like the BBC with a less defined idea of the audience—but our audience is in the USA.23

He also points out that the attacks in Europe this summer were significant because they represented a change in strategy by ISIS. They also raised fresh questions about community relations in those countries and the military/political strategy of governments in domestic and foreign policy areas.

The recent American terror events were also qualitatively different. The San Bernardino attacks were by “home-grown” extremists radicalized by online jihadist propaganda. The Orlando nightclub shooting was claimed by ISIS as inspired by them, although it seems the perpetrator was also driven by homophobia. Likewise, the Dallas police shooting challenged the usual frame of “terror” but it clearly had ideological motives, was connected to extremist groups, and sought to spread fear.

Journalists should always be reflecting on their editorial judgments and the quality of their coverage. Reporting by Western media of the European and American attacks tended to focus more on the victims. It used more emotive, compassionate, and outraged language. It stressed the surprise of the attacks, while the incidents in Lebanon, for example, were framed as just another tragedy in a violent region. More voices and detail from non-Western incidents would help redress the tonal balance, while more foregrounding of the connections with western politics would close the interest gap, too. These are perennial concerns regarding coverage of international stories but the paradox is that it is now much easier to cover distant events in the same way as “domestic” incidents.24The extent of the discrepancy is a matter of editorial choice and effort.

Quality, Context, and Constructive Reporting

Under the pressure of limited time and resources the news media is still a powerful and efficient resource for reporting and understanding complicated and challenging incidents. As the UK Editor of BuzzFeed, Janine Gibson, points out, the large amount of information around these events can paradoxically make creating a clear narrative more difficult:

Perpetrators now leave a much wider information footprint. They leave records of their lives on social media or they make videos and write messages. Friends or witnesses provide a whole load more material to sift through. We just know more about everybody. So the picture we try to build is much more complex and hard to simplify into the usual clichés.25

The audience now expects analysis and context almost simultaneously with reporting of the facts. Social media means that there is an instant explosion of often-erroneous information that presents the journalist with an additional task, that Gibson says BuzzFeed has taken on, along with its breaking news and background coverage:

In a breaking crisis situation, we usually set up a thread for “myth-busting” that will point out fake images or correct false leads and give basic background information. People expect us to do that and they trust us to do it. We ask readers to send us things they find and we will check it out. It’s a kind of media literacy and I think young people in particular feel pride in correcting mistakes seen on social or mainstream media.26

There are individual journalists such as Rukmini Callimachi of The New York Times who write compellingly, critically, and with a large reservoir of knowledge. Her lengthy piece based on an interview with a former ISIS member, for example, provided deep information on its organization, strategy, and training of recruits who then make up its diffuse international network. Research shows that this kind of narrative, using defectors, is effective in giving credible insights into terrorist motives.

Understanding the history helps understand the resultant terror attacks. The Financial Times special feature on ISIS’s dealing in the oil market was an outstanding use of interactive graphics that showed how the terror organization was funding itself and its links with international markets. This kind of background reporting is an essential supplement to the reporting of terror events. As media researcher Arda Bilgen has written, this helps with the “desecuritization” of narratives. Instead of concentrating only on the incident, the victims, and the drama of the disruption of normal life, this kind of objective, fact-based, nonpartisan reporting helps differentiate the various terror types and provide much-needed clarity.

Collectively, news teams now deploy new tools such as data visualization, video with text, and short-form explainers to enhance audience understanding across a wide range of platforms. These platforms, such as Snapchat, can also reach different demographics. “Digitally native” news organizations have been pioneers at finding new styles for gaining attention for these difficult topics. VICE documentaries on ISIS, for example, have gained remarkable access, and their style of less mediated, less formulaic reporting allows the audience a more direct insight into their subject.

Journalism must be independent, critical, and realistic, but there is opportunity for narratives of resistance, solidarity, and compassion. This would also help a fearful or jaded public engage with the issues and generate a more positive discussion about resilience in the face of the threat and a better quality of debate around “solutions,” according to Bilgen:

Implementing certain [editorial] policies that are different than the previous failed policies can facilitate the breaking of that cycle by forcing at least one side of the equation–the media–to act in a more responsible, more conscious, and more cooperative manner. Only then starving the terrorists of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend can become possible and more robust steps can be taken to win the ideological and actual battle against terrorism.

Perhaps most urgently, it would arrest a tendency towards Islamophobia. This is a problem for society, not just the news media. As Mary Hockaday, the BBC’s controller of World Service English, points out, this can be a question of responding to those who are themselves trying to create more constructive narratives around terror:

I thought it was very interesting that the Imams who attended the funeral in Rouen were quite clear they wanted to do it and needed to do it to “show” they are different. They fully understood image matters–and didn’t complain about needing to attend to that. It’s therefore really important that we the media report the voices who appeal to better nature, to peace, who show solidarity, and the people working hard and painstakingly at counter-radicalization. Not because I’m a softy, but because these things are also true and need to be said over and over again to counter the negative.27

One example of solutions-oriented journalism broadcast in the same week as the Brussels attacks was a short news film by the BBC that looked at Mechelen, another Belgian town with a high Muslim population, that seems to have avoided any significant radicalization through a policy of “zero tolerance” policing and outreach policies. It allowed the city mayor to explain his policies in detail and got high viewing figures.[102]

Journalism around terror events also has a role in mediating the emotional impact for the audience. There is an element of useful ritual about the creation of instant shrines at the scene of incidents, the memorial services, and the expressions of condolence. Social media and platforms now play a part in that, with special hashtags or profile flags to show solidarity. By showing this process of grieving, the news media helps communities recover from the trauma. By focusing on the victims rather than the perpetrators, journalists can bring humanity and dignity back into a narrative of destruction and fear. Samantha Barry of CNN explains:

Our audience tells us in a number of ways that they want us to focus on the victims. One of the most powerful pieces we did which achieved unprecedented levels of engagement across all platforms was when Anderson Cooper choked up reading the names of the Orlando victims. We try to be impersonal in how we report, but we are not robots. And the audience needs good news, too. Survivor stories are important as are those stories of personal courage such as the people who went back into the Bataclan nightclub to save their friends.28

Emotion used to be seen as an indulgence in hard news journalism, but when it comes to terrorism it is important to treat it as more than a commodity, especially with the advent of social media. Part of this is acknowledging the emotional impact of terrorist events on the journalist themselves.29 Anderson Cooper’s tears over the Orlando massacre run the risk of appearing too personally involved with the story. But it is possible to include feelings as part of storytelling without diluting factual and critical perspective. BuzzFeed’s Gibson says news organizations should be able to operate in different modes without compromising overall integrity:

With these events we are operating in three dimensions at the same time. We are simultaneously doing the breaking news, the analysis, and we are also sending reporters without a specific deadline to go find out what is going on—not to talk to the police but to talk to people to get the emotion behind the story. To go to vigils to talk to people to get their testimony but also to get the reasons why people were out and about in the wake of the event–seeing it from bottom up.30

Perhaps most important is to ensure that this is inclusive of the wider communities involved, be they the LBGT population of Florida or the Muslims of Europe. Humanizing terror’s victims and their communities may be the best counter-extremist measure media can provide.

Journalism, Terror, and Digital Platforms

This chapter will examine the increasingly important role of platforms such as Facebook, Google, Apple, and Twitter in providing information, connecting to journalism, and framing narratives around terror news events.

The Power of the Platforms

The major platforms are now increasingly the way the Western public accesses news about terror. Twitter, Facebook, Google, and Apple provide the infrastructure for mainstream news media to disseminate their material. Sixty-two percent of Americans now say they get news via social media. Sixty-three percent of American Twitter and Facebook users say they get news from those platforms, with Twitter especially popular for breaking news (59 percent). Facebook also owns the hugely popular social messaging apps Instagram and WhatsApp. Snapchat is increasingly used by news brands like CNN and Vice, who push content to users through Snapchat Discovery.

Platforms also aggregate news stories through Apple News, Google News, and Twitter Moments. They make deals with news organizations to feature journalism, further shaping the dissemination and consumption of news. They are also starting to provide new production tools for journalists such as livestreaming on Facebook and YouTube or through apps such as Twitter’s Periscope. Journalists have lost control over the dissemination of their work. This is a crucial challenge for the news media overall, but the issue is especially acute when it comes to reporting on terror.

The platforms provide an unprecedented resource for the public to upload, access, and share information and commentary around terror events. This is a huge opportunity for journalists to connect with a wider public. But key questions are also raised: Are social media platforms now becoming journalists and publishers by default, if not by design? How should news organizations respond to the increasing influence of platforms around terror events? Facebook is becoming dominant in the mediation of information for the public, which raises all sorts of concerns about monetization, influence, and control over how narratives around terrorist incidents are shaped.

As Guardian Editor Katharine Viner points out, we live in a world of information abundance, a world where “truth” is often harder to establish than before, partly because of social media:

Now, we are caught in a series of confusing battles between opposing forces: between truth and falsehood, fact and rumor, kindness and cruelty; between the few and the many, the connected and the alienated; between the open platform of the web as its architects envisioned it and the gated enclosures of Facebook and other social networks; between an informed public and a misguided mob.

It is in the public interest for these platforms to give people the best of news coverage at critical periods. But will that happen?

Facebook’s role in the dissemination of news is concerning because it is not an open and accountable organization. Recently, a Facebook moderator removed a story by Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten that featured the famous “napalm girl” image of a girl running from an attack during the Vietnam War. It was removed because the image violated the platform’s Community Standards on showing naked children. When Facebook deleted the image, Aftenposten’s editor accused Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg of “an abuse of power”:

I am upset, disappointed – well, in fact even afraid – of what you are about to do to a mainstay of our democratic society.

However, initially, even when the historic context of the image was pointed out along with its importance to the news story, Facebook stood by its stance:

While we recognize that this photo is iconic, it’s difficult to create a distinction between allowing a photograph of a nude child in one instance and not others.

Following a global outcry—including thousands of people posting the image on Facebook—they backed down and said they would review their policy and consult with publishers.