You’ve probably heard: The US Forest Service is savaging the First Amendment.

It’s trying to codify a provisional rule, in place for several years, regulating photography and filmmaking in designated wilderness areas. The rule amends the Forest Service Handbook to add criteria for the service to use when considering whether to grant certain photographers and filmmakers a permit to shoot in those areas.

If you followed the news last week, you might have concluded that (1) the permit requirement applies to all manner of photography and filmmaking, including newsgathering activities, (2) the permit costs up to $1,500, and (3) anyone who fails to get a permit when required, journalists included, faces fines up to $1,000.

Cue the outrage. And indeed, there are some genuinely concerning elements of the Forest Service rules.

But the situation isn’t exactly as it seemed at first, either. The early news reports and the Forest Service both misinterpreted the rule and its related provisions—in different ways. Since then, the coverage has gotten more precise, underlining some of the questions the government should answer before the rule is finalized. Still, it’s worth unpacking how we got here, and just what is at stake.

Here’s how the early coverage unfolded:

- Rob Davis, a reporter for The Oregonian, broke the story Sept. 23, writing, “[A] reporter who met a biologist, wildlife advocate or whistleblower alleging neglect in 36 million acres of wilderness would first need special approval to shoot photos or videos even on an iPhone,” with exceptions “only for breaking news coverage of events like fires and rescues.” Davis noted that “permits cost up to $1,500” and that violators “face fines up to $1,000,” attributing those figures to a Forest Service spokesman.

- Hunter Schwarz, a staff writer for The Washington Post, wrote the next day, “[S]till photography and commercial filming in Congress-designated wilderness areas would require a permit, and shoots would also have to be approved and meet certain criteria like not advertising any product or service and being educational.” Schwarz noted the $1,500 and $1,000 figures, citing Davis’ report.

- Eric Vilas-Boas, an assistant editor at Esquire, wrote Sept. 24, “[The rules] state that—across this country’s gloriously beautiful, endlessly photogenic, 36 million acres of designated wilderness area administered by the USFS—members of the press who happen upon it will need permits to photograph or shoot video.”

News spread quickly: Davis’ piece has been shared 24,000 times on Facebook, and Vilas-Boas’s piece 17,000 times. Soon, the Forest Service was clarifying (and/or backtracking on) just what the rule would do. Chief Tom Tidwell told The Associated Press Sept. 25 that the rule “does not apply to newsgathering activities.”

The same day, the Forest Service released a statement saying that “provisions in the [rule] do not apply to newsgathering,” and that the rule “pertains to commercial photography and filming only.” The statement also said the $1,500 permit fee “cited in many publications is erroneous.”

Those assurances didn’t entirely square with the text of the rule, or earlier Forest Service statements. The AP highlighted some of the discrepancies, and at The Oregonian Davis covered them in back-to-back follow-up stories. Although his original piece missed the mark a bit, as I explain below, his reporting was evolving and becoming more nuanced.

“The Forest Service initially told us,” Davis told CJR, “that the [rules] would apply to news organizations … planning to use the material to raise money, sell a product, or otherwise realize compensation in any form (including salary during production). The only exception would be for breaking news.

“By late last week, the chief announced the agency wouldn’t be interpreting the rules that way. That changed the tenor of our characterization of the rules. … Still, as we’ve continued to note, a wide gap remains between what the chief said about the rules’ intent and what they say.”

The Forest Service Press Office did not respond to a request for comment.

The letter of the rule

The rule itself amends part of the Forest Service Handbook, section 45.51b, which sets out the criteria the Forest Service uses to decide whether to issue a permit for still photography and commercial filming in designated wilderness areas. Specifically, the new rule adds criteria for the service to use in that process.

The rule’s first few words are: “A special use permit may be issued (when required by sections 45.1a and 45.2a) to authorize the use of National Forest System lands for still photography or commercial filming …” (emphasis added). Those sections contain the permit requirements for still photography and commercial filming, respectively.

Under the still photography section, a permit:

1. Is required for all still photography … activities on National Forest System (NFS) lands that involve the use of models, sets, or props that are not a part of the natural or cultural resources or administrative facilities of the site where the activity is taking place.

2. May be required for still photography activities not involving models, sets, or props when the Forest Service incurs additional administrative costs as a direct result of the still photography activity, or when the still photography activity takes place at a location where members of the public generally are not allowed.

The section also states: “A special use permit is not required for still photography when that activity involves breaking news.”

Next, under the commercial filming section, a permit “is required for all commercial filming … activities on National Forest System lands.” Again, a permit “is not required for broadcasting breaking news.”

Obviously, we need to define some terms to evaluate the implications. The handbook defines still photography circularly as taking pictures using models, sets, or props that are not naturally part of the site; or taking pictures in a restricted area of the wilderness, or in a manner that imposes costs on the Forest Service.

Meanwhile, the handbook defines commercial filming as an audio or visual recording whose purpose is to generate income—excluding “activities associated with” broadcasting breaking news, which the handbook defines as “[a]n event or incident that arises suddenly, evolves quickly, and rapidly ceases to be newsworthy.”

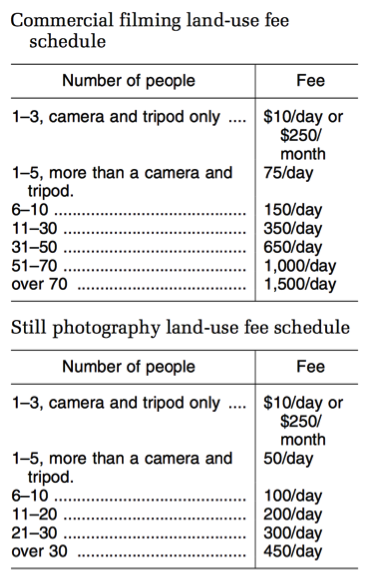

And, finally, the permit fees. According to a separate entry in the Federal Register, the fee schedule runs from $10 per day to $1,500 per day, depending on the number of people involved and the type of project. There’s no mention of fines.

So: Is the Forest Service savaging the First Amendment with its permit requirements?

The implications for press freedom

The starting point is breaking news. If a photography or filmmaking project doesn’t qualify for that exemption, it may be subject to the permit requirements. That’s problematic because the definition of breaking news is narrow, given its emphasis on currency. It excludes not only journalistic enterprise and feature photography and filmmaking but also Ansel Adams-type work. As press freedom advocates have noted, if the Forest Service doesn’t intend for these criteria to apply to any newsgathering, it should change the text of the rule to say so.

Still, even if a project doesn’t qualify as breaking news, a permit is required only if the project meets the conditions under 45.1a or 45.2a, the sections containing the permit requirements, respectively, for still photography and commercial filming. Otherwise, the permit doesn’t come into play.

Notably, the photography section is not as sweeping as the early news reports claimed. For example, recall that Davis wrote that a journalist “who met a biologist, wildlife advocate or whistleblower alleging neglect in 36 million acres of wilderness would first need special approval to shoot photos or videos even on an iPhone.”

That’s not quite right. 45.1a focuses on taking pictures using models, sets, etc., that are not naturally part of the site; or taking pictures in a restricted area, or in a manner that imposes costs on the Forest Service. By the text of the rule, as long as the journalist doesn’t trigger one of those conditions, she doesn’t have to get a permit.

The filmmaking section, though, is not as narrow as the Forest Service has claimed. For example, recall that Tidwell told the AP the new rule “does not apply to news-gathering activities.” But the handbook’s definition of “commercial filmmaking” is broad:

Use of motion picture, videotaping, sound-recording, or any other type of moving image or audio recording equipment on NFS lands that involves the … creation of a product for sale. … For purposes of this definition, creation of a product for sale includes a … television broadcast …, when created for the purpose of generating income (emphasis added).

The income phrase is vague and plausibly would require, at minimum, broadcast journalists covering non-breaking news for a commercial station to get a permit. Davis, of The Oregonian, has reported that he initially was told by a Forest Service spokeswoman that “reporters shooting videos, even on iPhones, would need special permits.” He’s right to continue hammering that point.

Most troubling, though, are the new criteria the rule creates for the Forest Service to use when deciding whether to issue a permit. Let’s say a project requires a permit—it’s for a non-breaking news piece, in the form of commercial still photography or an audio-visual recording, the two forms of expression subject to the new criteria. The Forest Service may grant the permit if the project meets this criterion, among others:

[The project has the] “primary objective of dissemination of information about the use and enjoyment of wilderness or its ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical value.”

As Gabe Rottman of the ACLU pointed out, that language is so vague it could be used arbitrarily by Forest Service officials to block projects that depict poorly the service or any other government entity. That’s fundamentally incompatible with the press’s general rights to report information free from government interference or influence.

Again, that criterion applies only when a permit is required, and for a variety of reasons it appears a permit won’t be required as often as the early reports suggested. Still, it’s a creepy suggestion of message control, and the sort of thing press freedom advocates might object to. You can do that here.

Update, 10/1: A coalition of news organizations and advocacy groups this evening expressed concern about the proposed rule in a letter to Thomas Tidwell, the Forest Service chief. “We contend the proposed permanent policy limits far more speech than is necessary to achieve the government’s stated purpose,” wrote Mickey Osterreicher, general counsel for the National Press Photographers Association. “[W]e strongly urge the Forest Service to include us in any public meetings and then continue to work closely with us to craft an unambiguously worded policy that protects not only our natural resources but our First Amendment guarantees.”

Jonathan Peters is CJR’s press freedom correspondent. He is a media law professor at the University of Georgia, with posts in the Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication and the School of Law. Peters has blogged on free expression for the Harvard Law & Policy Review, and he has written for Esquire, The Atlantic, Sports Illustrated, Slate, The Nation, Wired, and PBS. Follow him on Twitter @jonathanwpeters.