On the afternoon of Wednesday, August 28, as the Democratic National Convention was called to order by Chairman Carl Albert on the floor of the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, I was sitting at the back of the Central Control Room of the Columbia Broadcasting System convention headquarters several hundred feet away, watching the proceedings on a bank of monitors and listening to the talk on the Central Control intercommunications system among the men who were in charge of various aspects of the CBS coverage. I was there to try to get some sense of the process of communication involved in the portrayal of a modern political convention by a great television network. As it happened, I was to get something else, too: a sense of the problems involved in the television coverage of a confrontation between the myrmidons of established political authority and modern political protestants.

Although the television editorial process embraces many stages of preparation and selection, for my purposes Central Control was the best place I could think of to take in both the final televised act itself and the flow of material contributing to it, and to obtain some feeling of the editorial judgment being exercised in the compilation of the stream of images that went out on the air to the tens of millions of people watching CBS on their home screens that day. Network coverage of political conventions is a massive logistical undertaking. For CBS in 1968, it involved the deployment, first to Miami Beach and then to Chicago, of some 800 people—engineers, camera crews, trouble-shooters and expediters of all kinds, news writers, directors and producers, and on-the-air correspondents and commentators—and of perhaps two hundred tons of very complex and expensive equipment, including huge self-contained trailer or mobile van units housing a staggering array of electronic gadgetry, office trailers, and control rooms, as well as mobile electronic camera units. In addition to transporting all this equipment to Chicago and arranging it in a cluster interconnected by a highly intricate wiring system, in a large warehouse-like area forming part of the International Amphitheatre building, CBS News had also erected, within the Amphitheatre itself, two fixed installations that overlooked the convention floor—its anchor booth for Walter Cronkite, the CBS anchor man, and a much smaller booth, very high up on one side of the Amphitheatre, from which the work of the CBS News correspondents on the convention floor could be directed. Also, just outside the convention floor, CBS had erected a large newsroom and another television studio, called the analysis studio, from which Eric Sevareid and Roger Mudd were to make periodical commentaries or to interview political figures.

Besides the Central Control Room, CBS had several other trailer control rooms into which television images flowed and in which editorial judgments were made. These included Perimeter Control, which received the output of cameras placed outside the entrances to the convention floor and from immediately outside the delegates’ entrance to the Amphitheatre building, and Remote Control, which, with another trailer control room called Videotape that was served by five videotape recording and storage vans, received the output of electronic and film camera crews at the Conrad Hilton Hotel—the headquarters for the Democratic National Committee—and the Blackstone Hotel in downtown Chicago, and from roving crews on assignment around the city. Because of a long-standing strike of telephone workers in Chicago that made impossible the installation of remote microwave transmission equipment in the city, live coverage of activities in Chicago concerning the convention was limited to the International Amphitheatre. Thus, whatever images were fed into CBS headquarters at the Amphitheatre from downtown arrived there in the form of videotape or film sent by courier to the Videotape Room, from which it could be fed to the Remote Control Room.

From all the control rooms through which such streams of images passed, after a preliminary editorial straining that might select, say, the output of two television cameras out of eight that were available, tributary streams then flowed into Central Control. There, from a large bank of monitors, the shots that actually were to go on the air could be finally selected. Physically, Central Control consisted of two huge trailers placed side by side, with one wall of each removed so as to produce a large unobstructed area, and this area was further increased by the addition of a fixed enclosure between the two open sides. The focal point of Central Control was the bank of monitoring screens I have referred to. There were five rows of screens and individual monitors identified by such titles as “CAM 1,” “CAM 2,” “REMOTE A,” “REMOTE B,” “PERIMETER A,” “PERIMETER B,” and so on. Before this bank of monitors were two long rows of consoles staffed by technicians and production people, including Vern Diamond, CBS News Senior Director; Gordon Manning, a CBS vice-president who is Director of News; and Robert Wussler, executive producer and director of the CBS News Special Events Unit. Wussler, who is in his early 30’s, is a round-faced man with a large forehead and rather prominent eyes. He has a controlled manner and a flow of energy that round-the-clock working habits seem in no way to diminish. It was essentially through Wussler’s marshaling of subject matter, usually minutes ahead of its actual appearance on the air, that the general pattern of the CBS coverage seemed to emerge. Wussler sat in the center of the second row of consoles, wearing a microphone-earphone headset, and in front of him he had an intercommunications box connecting him with each of the producers in the various sub-control rooms: Robert Chandler in Perimeter Control; Bill Crawford in Videotape; Casey Davidson and Sid Kaufman in Remote Control; Paul Greenberg in Floor Control, a small booth high up in the Amphitheatre from which the work of the CBS floor correspondents was guided; Sanford Socolow, the producer attached to the anchor booth; and Jeff Gralnick, an associate producer who sat next to and was the immediate liaison with Walter Cronkite, the anchor man, or, as he was sometimes simply referred to on the intercom, “the Star.” Through an extra earphone I was able, while sitting in Central Control and watching the bank of monitors, to hear Wussler’s conversations over the intercommunications system with all his producers, as well as with Diamond, who had responsibility not only for the direction of cameras on the convention floor but also for the exacting job of choosing, from among the bank of monitors, shots that actually went on the air. That Wednesday I was able to see and hear how, in this nerve center, CBS News went about the business of informing its audience on subjects that included the debate on the issue of that part of the Administration-backed platform dealing with the war in Viet Nam, and also, later on that evening, the violence that was to erupt between police and anti-war demonstrators, and other events in downtown Chicago.

On that day, CBS had been on the air since 12:30 p.m., Eastern Standard Time. The proceedings at the convention were opened at 1:08 p.m. by Chairman Albert—only eight minutes after the scheduled time. (Three weeks earlier, in Miami Beach, the Republican National Convention had broken all convention records by actually starting exactly on time.) Now Chairman Albert started things off by bringing forward Mahalia Jackson to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Between the start of the CBS convention programming and the convention opening there had been a number of interviews with delegates by CBS floor correspondents. Walter Cronkite had told the television audience that the previous day’s boom for Senator Edward M. Kennedy had been finished by a statement by Kennedy that he was not available for the nomination. (This alleged boom actually had never got beyond the stage of a few sputtering fuses, most of which had the appearance to me of having been lighted around the place by eager network floor correspondents rather than by Kennedy’s men. I had seen how, after these correspondents had been pumping away for a few hours at the notion of a Kennedy boom, a number of hand-lettered “DRAFT TED KENNEDY” signs, got up by people who presumably were not unaware of what the correspondents were saying on television, began to appear on the convention floor. When the signs appeared, the television cameras that were endlessly panning around the hall searched them out as visual confirmation of the so-called boom. It seemed to be a case of Kennedy signs and Zoomar lenses encouraging one another.)

While Mahalia Jackson’s image was on the screen marked LINE in the center of the bank of monitors in the control room, showing that it was on the air (this image was a duplicate of another, directly above it, marked POOL, which was the product of one of several cameras operated jointly by the three networks to cover proceedings on the podium), other monitors were showing a variety of scenes being recorded by CBS cameras, but not being fed to the air. On these monitors, there was a great variety of movement—shots in which one camera after another would be panning the convention floor, constantly zooming and searching, homing in now on one delegate and now on another. Sometimes the cameras would be just slewing around in apparently aimless fashion. The effect on me was an extraordinarily dizzying one. It was something like watching the outside world through the windows of a train, except that as seen through adjacent panes parts of the scenery seemed to be moving not in one but in quite different directions. Through some windows, the view was flying to the right, through others to the left. In yet others, it seemed as though the train itself must have suddenly thrown itself off the tracks, moved sideways at express speed, plunged down an embankment, suddenly stopped short within a foot of a man’s face. Then, as abruptly, it would reverse its course and pull off in yet another direction.

As I watched this array I could hear, on my car phone, Wussler talking with his producers.

“Next, we’ll go to Walter,” Wussler told them. “Walter will throw it to a New York commercial and a station break, and out of that if we can fit it in we’ll get in that piece on the Illinois caucus—it’s on Videotape Number Four.”

“Bobby, there’s a CND [Columbia news division] story that McCarthy is coming to the convention this afternoon,” Gralnick’s voice said, as Cronkite, on the air, said a few words that served as a transition from “The Star-Spangled Banner” to a commercial for Zest.

About 1:30 p.m., Kenneth O’Donnell had just finished telling Josh Darsa, a CBS News reporter, that Humphrey might well be better off running against Nixon, whom he called “the super-hawk,” on the minority Viet Nam plank rather than on the majority plank. Then Greenberg’s voice came in on the intercom, “Are you interested in Charles Evers? He’s a dove.”

“Mmmm, we just had a dove on,” Wussler said. “I’d like to get a—”

“You want a hawk?” Greenberg said. “How about Governor Connally? The biggest hawk that ever took wing.”

“Aaah, we’ve had him on the air so much,” Wussler said.

“He’s the biggest hawk on the floor,” Greenberg’s voice said, in eager tones.

On the bank of monitors I could see shots of Roger Mudd and Art Buchwald, who were sitting together rather glumly at the analysis desk, and of Cronkite in the anchor booth, and of Carl Albert on the podium. Alongside the shot of Albert there was a practice zoom-in-and-out shot of Governor Connally, who was standing on the floor with Dan Rather.

“Okay, let’s go Rather-Connally,” Wussler said.

“… Dan Rather is with Governor Connally of Texas on the floor there,” Cronkite said, almost after an echo’s interval. Instantly, the image of interviewer and interviewee on the monitor multiplied itself and sprang onto the screen marked LINE.

Rather said, on the air: “Governor John Connally of Texas, how do you think this platform vote is going to go?”

On the intercom, Greenberg said, “Bob Wussler, Mike Wallace is offering Burns, the state chairman of the New York delegation, on the possibility of nominating Johnson.”

Connally was telling Rather that the minority plank “just does not reflect the feeling of the people of this country.”

“I think they’re getting down to business on the podium, Bobby. Boggs has the gavel,” Socolow’s voice warned on the intercom.

“Interested in the possibility of Chairman Burns nominating Johnson?” Greenberg’s voice persisted.

“We’re getting into Viet Nam, Paul, so we’ll cool it for a while,” Wussler told Greenberg. Wussler added, referring to the onscreen interview with Connally, “Wrap him up. Wrap him up!”

The order was relayed immediately. “Governor, one last question,” Rather said, on camera, within two or three seconds, “How much of this is personal animosity to President Johnson?”

On the bank of monitors, I saw Art Buchwald being made up at the analysis desk. What he was going to say before the cameras—which was how much he missed the presence of Lyndon B. Johnson at the convention—was to be recorded on videotape for later use. Another monitor showed a delegate on the floor reading a newspaper. On the monitor marked LINE, Congressman Boggs was introducing Congressman Phillip Burton.

“And thus (And-a thuss) the debate begins,” Cronkite’s voice, with its characteristic syllabic pump-rhythm, sounded over the image.

“Love to use that Wallace story on Johnson, Greenberg. But we gotta stay on the platform now,” Wussler said.

And, with the exception of a few intercutting shots of the hall and of individual delegates in close-up, the cameras stayed pretty much on speaker after speaker—in turn, one representing the minority plank on Viet Nam, one representing the majority plank, and so on—for the three hours of the debate. From the anchor booth, Cronkite intervened only occasionally. With this emphasis on straightforward relaying of the sound and sight from the podium, Wussler’s intercommunications system grew relatively quiet, with only occasional advisories: “Bobby, the Illinois caucus has just broken—112 votes to Humphrey. We have videotape coming back with Daley saying it”; “The spotter has told us that if the minority report is defeated the South Dakota delegation is going to set out to have people wear black armbands all over the floor”; “Dan Rather, offering a spot about Connally’s people smuggling bullhorns onto the floor—they say that if the majority plank on Viet Nam is accepted they’ll stage the loudest demonstration you’ve ever heard.”

After about an hour and a half of the debate I went out of the Central Control Room, picking my way along narrow plywood corridors through a maze of CBS trailers, out of which, at the sides, great bundles of cables spilled, some of them fat like entrails, others finer, with multicolored strands like the exposed nerves in an anatomical drawing. I wandered around to the CBS newsroom, loud with ringing phones, urgent voices, the incessant riffle of typewriters, the line-by-line chugging of news tickers and the sounds of the CBS convention coverage coming from a loudspeaker near a row of three network monitors that also showed what NBC and ABC were putting on the air. From the nearby office of William S. Leonard, a CBS News vice president who is Director of News Programming, I managed to borrow for a very short time one of the extremely scarce passes that gave the bearer access to the CBS anchor booth overlooking the convention floor. After running the gantlet of suspicion through seemingly endless checkpoints of Secret Service and other security men, I reached the doorway of a small producer’s booth immediately adjacent to the anchor booth, and overlooking it through two glass windows. Through one of these windows I could see Cronkite, sitting in bright lights at the anchor desk, and behind him, even more brightly lighted and compressed into a garish mosaic, the crowd on the convention floor and galleries. Socolow was there in the little producer’s booth. Near him, a couple of people were tapping out, in oversized print on electric typewriters, pieces of copy for Cronkite to read before the cameras.

Socolow took me into the anchor booth itself, and for a minute or two I stood between two cameras that were trained on Cronkite at the anchor desk. The red lights on the cameras were off momentarily, indicating that Cronkite wasn’t on the air. Cronkite’s desk was semicircular, faced with teak veneer, and it had set into its top, out of view of the audience, several monitors. Next to Cronkite, three feet or so to his left, was Gralnick, the Star’s primary contact with the whole CBS communications machine that was geared to feed information toward him. When Cronkite and his whole anchor desk were visible on the air, Gralnick was out of sight because his seat was down at the floor level, so that he sat with his legs in a small pit sunk into the studio floor; this pit was filled to the brim with monitors, and when I moved over to one side to make a closer inspection of it, I could see that Gralnick’s shoes were in a certain amount of debris—crumpled papers blacked with footmarks, an occasional sandwich wrapper. From this nether world, Gralnick’s job was to cue Cronkite, to hand him bulletins, brief handwritten notes (“MUDD-SEVAREID NEXT”; “WRAP UP DARSA”). However, Gralnick, as he told me later, didn’t have to sit in his hole out of sight too much, because usually the cameras could be trained on Cronkite so as to exclude him. At the moment, Gralnick was standing in his pit. Cronkite, swiveled around in his chair, was scanning the rear of the convention floor area—“eyeballing it” as one of his men described such a direct view. To improve his view, Cronkite picked up a pair of binoculars and focused on a particular area on the floor. Pierre Salinger had just finished a speech for the minority plank, and a demonstration was going on, particularly in the California and New York delegations, with loud chants of “Stop the war!” “I notice there are people down there who seem to be cheerleaders in these delegations,” Cronkite told Gralnick and Socolow as he peered through his binoculars. “You ought to pass that on.”

“I’ll get that to Greenberg,” Socolow said.

I left the anchor booth, found my way back to Leonard’s office, and after an interval returned to the Central Control Room. Onscreen, Congressman Hale Boggs was making a summation of the majority plank. Off-screen, Greenberg, in Floor Control, was reporting excitedly to Wussler that Mike Wallace had a story that a telegram had been received from Ted Kennedy that Kennedy wanted read to the convention; the telegram said that he supported the minority plank. Greenberg let Wussler know where on the bank of monitors Wallace could be seen: “He’s right in that pile of people on Camera Three and he’s also on Five. Five is probably a better shot.” He added, pleadingly, “Can you go?”

“I can’t go during Hale Boggs,” Wussler said.

“This is really something. The opposition will have it on the air in a second,” Greenberg said. “Dick Goodwin is standing near Mike. And vanden Heuvel. Mike can talk to them about it.”

Wussler, for several seconds, was silent. Finally, he said, “We’re going to give it to Walter right now.” He repeated Greenberg’s information for Gralnick’s benefit.

On the air, Congressman Hale Boggs was saying, from the podium, “I would turn, too, to another area on God’s earth—the Middle East. The Middle East, my friends… a powder keg….”

On the bank of monitors, the screen emanating from Camera Five zoomed in close-up on Mike Wallace, standing on the convention floor.

“We’ve got a clean beat on this—we’ve got to go!” Greenberg said.

Gralnick’s voice said, “Bobby! Bobby Wussler! Walter says he’d rather Wallace took it if you want to cut away from Boggs—he doesn’t think it’s important enough to cut away from the summary.”

“It’s Teddy Kennedy, supporting the minority plank,” Wussler said, in a tone of exhortation.

“I told Walter,” Gralnick said.

Socolow’s voice cut in. “Walter’s point is that it’s only a matter of another minute or so before Boggs is finished. Then we can go,” he said.

Greenberg’s voice came in, anguished from what he saw on his monitors upstairs. “Here comes NBC, for Christ’s sake!” he cried. “Here comes Vanocur!”

“Well, we’re moving! We’re moving!” Wussler said.

“Yeah, but we’re gonna lose it!” Greenberg said.

“Jeff, tell Walter we’re going to go to it. We’re going to go to it now,” Wussler said.

“Come on!” Greenberg’s voice said, agonized.

Gralnick, in a deliberate voice, said, “Walter says you’ll have to bring Mike up cold.”

Wussler did not answer immediately. “Did you hear that?” Gralnick said.

“Okay,” Wussler said. He went on. “Wallace, stand by. I’m going to you direct. Walter will not intro it.”

Gralnick’s voice came on again. “Bobby,” he said. “Do you realize you’re interrupting a majority summation to deal with the minority report?”

Wussler, cutting his microphone off, leaned over and conferred with Manning next to him, and in a few seconds he told Greenberg that “we’ll stay with Boggs and then throw it to Mike.”

CBS did allow Boggs to remain onscreen for the rest of his speech. And then they threw it to Mike. I gathered that the Star was not pleased.

After the debate had ended, and as the state-by state vote on the minority report was being counted, Cronkite made a reference on the air to “a considerable erosion of the pro-Humphrey vote on the anti–Viet Nam plank.” A while later, Wussler broke in on the intercom to Gralnick, “Jeff, try to get Walter not to use the word ‘erosion’ away from Humphrey. We’re getting a lot of heat from on high about this.”

“I’ll write him a gentle note,” Gralnick said.

“Jeff, it’s only the word ‘erosion’ they’re objecting to,” Wussler said. (This word had been used a great deal by Cronkite and other CBS correspondents at the Republican convention, and had been the object of some derisive comment in the press.)

Gralnick, after a few seconds, said, “Mr. Cronkite just answered the note with [enunciating carefully] ‘I quit!’ ”

“Did he?” Wussler said.

Socolow’s voice said, “And he gesticulated at Jeff so that Jeff would pass the word back to you and Manning.”

“He’s serious!” Gralnick said.

In the Central Control Room, I could see Wussler and Manning scrutinizing the bank of monitors in front of them with unusual attention. On the various monitors were shots of the podium, a close-up of a lady delegate with a large hat, a bleak-looking shot at the perimeter of the hall showing people wandering by with apparent aimlessness. On the anchor booth monitor there was the off-the-air image of Cronkite, leaning back at his desk and looking very annoyed.

But the Star had time to regain his composure as the business of calling the roll and registering the state-by-state votes in the convention hall went on. During this formal process, I was interested in how the rows of images on the monitors, normally so utterly restless and diverse in their movement and direction, became relatively still, with only an occasional zoom in and out from one camera shot of a particular delegation reporting its vote to the next delegation in line. Then, when the delegate vote for the Administration plank exceeded the 1,3111/2 needed to pass, the whole array of monitors began moving once again, with an agitated, swarming quality.

As camera next to camera swiveled, slewed, and panned, and as images zoomed in and out among delegations, searching out subject matter, fixing on floor correspondents with their headsets topped by man-from-Mars antennas, their wireless microphones and instant questions, the bank of monitors in front of Wussler and his companions in Central Control took on, for me, the character of a sort of bazaar—a set of simultaneous visual offerings. I would almost call them enticements. Every camera at the convention, and every producer behind it or reporter before it, might be intended to serve as an extension of some central directorial sense, but I had a strong feeling that if he were such an extension, every man whose person or work was appearing on a monitor in Central Control was there also as an expression of a strong competitive drive—competition not only against the work of other networks, but against his own colleagues at CBS News. (“Believe me, every time that red light on the camera lights up and you’re on, you’re putting your ego right on the line,” the CBS News correspondent Hughes Rudd told me later. And Dan Rather told me, “Yes, I’m competitive, all right. When I go out there on the floor, I want to be on camera beating the other guy. I want in. I want to be the biscuit company.”)

The resulting, final image on the central air screen represented for me a correspondence to reality, but it was an image of reality peculiarly heightened and shaped, particularly by chronological juxtaposition of segments of simultaneously occurring images. It was an effect produced, really, by an editorial process unlike anything we have ever seen before—as different from any other editorial process as tennis is from croquet. Disregarding, for the moment, gross distortions of live actuality that would be apparent to everyone, it seemed to me that the nature of television makes it peculiarly difficult for one to divine its ability to perceive reality by attempting, just to separate original action from the series of the electronic images representing it, because what is involved is not merely the subject before the cameras or the instant editorial process but also the immediate reaction of the universal audience. The reality of the televising process consists only of the whole works—an entire cybernetic complex of mutually and instantly adjusting elements, in which the act of observation itself inherently tends to modify that which is under observation. The process is something like a man walking down a corridor of mirrors, along which not only his reflections change but the man himself somehow alters as he goes.

Sometimes the reflection even eliminates the subject. On Wednesday, the networks showed shots of delegates reading newspapers during speeches from the podium; on Thursday, the Democratic National Committee deprived them of the chance to get similar shots by having security guards refuse entrance to the floor of any delegates carrying newspapers. On Thursday, too, while Hubert Humphrey was making his acceptance speech, Greenberg, in Floor Control, noticed a little man behind Humphrey who was wearing a microphone headset. Using the CBS floor cameras as telescopes, Greenberg began to explore the connection between the behavior of this little man with that of the convention bandleader on the opposite side of the hall, who also had a headset and, it seemed, a copy of Humphrey’s speech.

Every lime Humphrey paused for applause, a signal was passed to the little man by J. Leonard Reinsch of the Democratic National Committee, who was also sitting behind Humphrey. The little man said something urgently into his microphone, and across the hall the bandleader immediately raised his baton and had his men strike up hearty chords to swell the noise of the applause. Then Greenberg’s shots of the three men were fed into Central Control in the form of two intercuts, one immediately following the other, without any accompanying verbal explanation of the connection between the little man, Reinsch, the bandleader, and the applause. But when that happened, Reinsch, who himself was equipped with network television monitors, could be seen on the bank of Central Control monitors looking with suspicion at the shots he was seeing of himself and his crew on television. The result was that Reinsch said something to the little man, and thereafter, for a long time, when Humphrey paused for applause, the little man deliberately withheld his signals to the bandleader, who could be seen on the CBS monitors looking absolutely baffled that he couldn’t get the sign to do his bit in a Presidential nomination acceptance speech cued for music.

A while after having Cronkite declare that he was quitting, I ran into Mike Wallace in the CBS newsroom. Wallace is a gregarious, fast-talking man with a slightly pockmarked face that used to look somewhat sinister when he ran an inquisitor style interview years ago on New York’s Channel 5. Wallace’s expression now conveyed an air of cheerful, non-stop push. He had his headset off and resting around his neck. He was also wearing other elements of miracle transistorized audio broadcasting gear in the pockets of the gray gabardine vest that was standard equipment for the CBS News floor correspondents. Actually, these were fishing vests from Abercrombie & Fitch, specially adapted for CBS to use to hold batteries and miniature receivers and transmitters. “I have California with 174 delegates, and New York with 190, and eight other delegations to cover. It’s hard to hustle around down there on the floor,” Wallace told me. “The aisles are smaller than they were at the Republican convention in Miami Beach, and just finding people is so much more difficult. In Miami Beach, every Republican delegate wore a tag with his name and the state he represented. Here there are no name tags, and often no identification of the state.”

I told Wallace that I had noticed on the monitors how delegates the floor correspondents lined up to interview were sometimes kept waiting quite a while before they went on the air, and that sometimes even after such delays the correspondents let them go; and I asked him if the subjects raised any objection to this waiting around.

“Very few of them are unwilling to wait,” Wallace said. “Very few. Some of them are willing to do it to help you out, and of course some of them do it because they want publicity. They’re acting out their thing, and it’s difficult for them to act it out in solitary. I guess they’d rather act it out in prime time.”

A little more than four hours later, after the debate had ended with the adoption of the Administration plank, the first of the nominating speeches—a favorite-son harangue on behalf of Governor Dan Moore of North Carolina—began, and I went into Central Control once more. Cronkite, on the air, was saying something about there being no doubt that it was Hubert Humphrey all the way, and he went on, after a floor interview by Ike Pappas with Mrs. Frances Howard, Mr. Humphrey’s sister, to say that he had got word that anti-war demonstrators were around the big hotels downtown and had got particularly unruly; they were even said to be battling in the lobby of the Conrad Hilton Hotel; he added that tear gas was reported to have drifted up even to Vice-President Humphrey’s suite in the hotel.

Then Mike Wallace, interviewing on the floor, looked around and told Cronkite excitedly, “I see a battle going on over here near the New York delegation.”

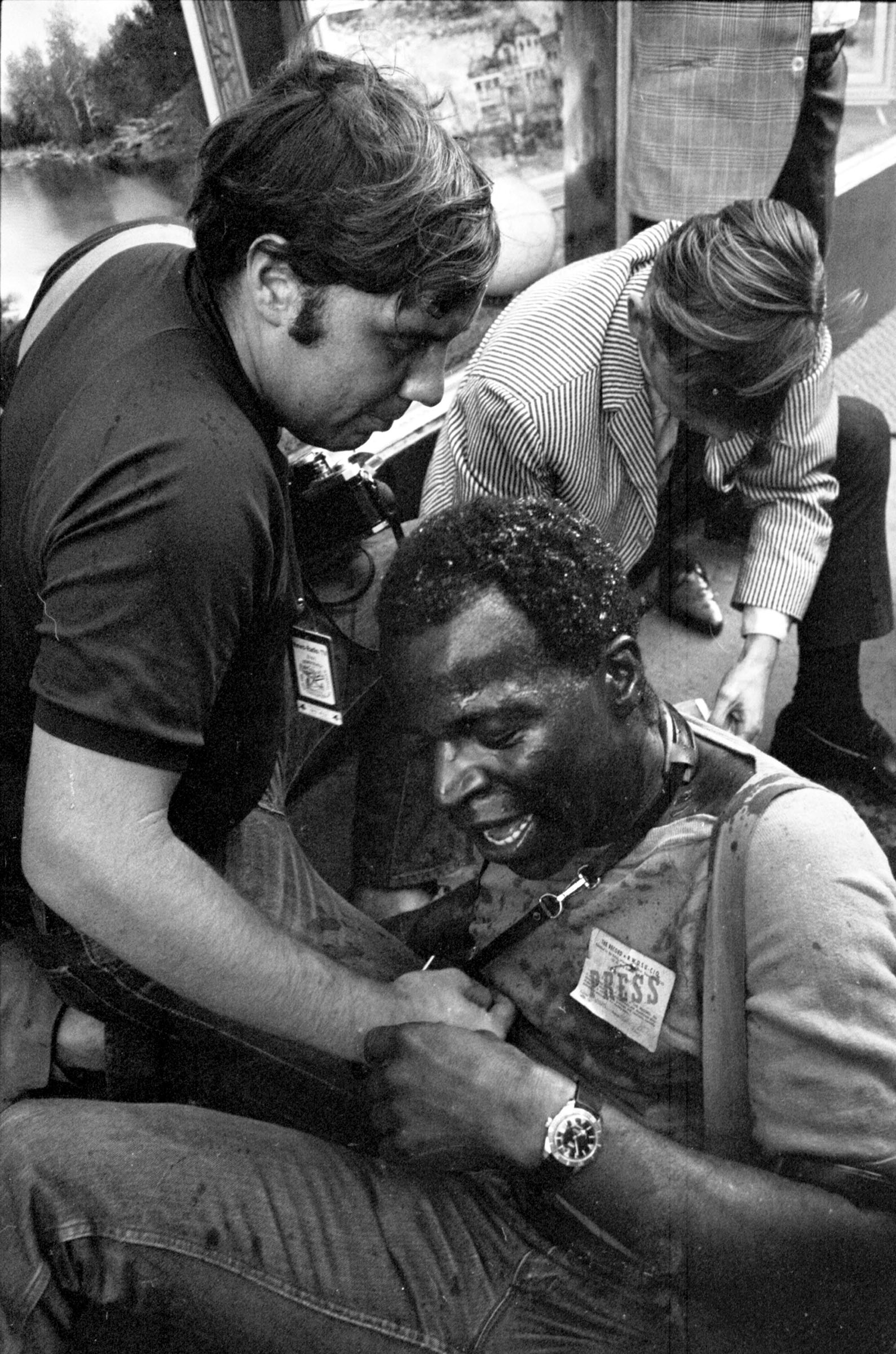

“Yes, I can see them carrying a man out bodily,” Cronkite’s voice said, over an on-the-air shot of Wallace, who quickly hustled his way over to the area of trouble. “Sergeant-at-arms, why are you doing this—who is the man?” Wallace cried.

The man was a Manhattan delegate named Alex J. Rosenberg, who, apparently after having become indignant at repeated demands by security men on the floor that he show his credentials, had refused to do so and had been collared by the security people. In the resulting melee, I could see Wallace himself being pushed around; his headset was coming off, but he somehow kept talking into his microphone: “Now come the strong arms! The Chicago police, wearing hard hats.” From one of the monitors, a shot of helmeted police with billy clubs, muscling their way onto the floor, became replicated and jumped to the central air monitor.

“Oooh!” Wallace said.

“Yes, Mike, I saw you shoved down by those fellows,” Cronkite’s voice said, on the air. Then, with increasing indignation: “A duplication of the Dan Rather scene last night.” He was referring to a scene the previous evening when Rather, accompanying Georgia delegates who were walking off the floor, had been punched in the stomach and thrown to the ground by one or more of the security plainclothesmen at the convention—causing Cronkite to exclaim in front of the CBS audience, “I think we’ve got a bunch of thugs here!”

On the intercom, Wussler said, “Call in Dan!”

“It’s a roughhouse situation.” The voice of Dan Rather, who could now be considered something of an expert on the subject, and who had already homed in on the trouble, came over the on-the-air scene of chaotic milling around: “This is by far the roughest scene of the convention so far.”

“Where’s Mike?” Wussler said on the intercom. He was scrutinizing monitor after monitor in front of him.

“Bobby, Socolow tells me he thinks Wallace is under the anchor booth,” Gralnick said.

“We’ll look for him on camera,” Wussler said. “Greenberg, where do you think Wallace is?”

“Under the anchor booth. That’s where he went out,” Greenberg’s voice said.

On the bank of monitors, camera shots restlessly zoomed in and out and swiveled around over the heads of crowds.

Different voices came on the intercom:

“I’m told the police have taken him to McGovern headquarters.”

“Are you interested in Senator Mondale of Minnesota, with Dan Rather—do him in a seconding speech?”

“Mike is in custody. We believe he’s in one of the police trailers outside.”

“Greenberg, who do you have on the floor?”

“Senator Mondale.”

“No, no, no, NO! What reporters do you have on the floor?”

“It seems that Mike got into an argument with a cop outside.”

“Senator Mondale is down on the floor with us, waiting. When can we get to him? He wants to go.”

“The cop belted him. And they arrested Mike.”

On the air monitor, there was a succession of shots following a speech by Governor Harold Hughes of Iowa placing the name of Senator McCarthy in nomination: people cheering, confetti fluttering down, people waving “Peace” signs and McCarthy posters designed by Ben Shahn.

Gralnick’s voice, low but enunciating very distinctly, said on the intercom: “Downtown Chicago is blowing up.”

“We have videotape in on the rioting,” another voice said.

As soon as the McCarthy demonstration was fairly well over (and a total of seven commercials, relieved only by a station break, had followed), a section of videotape showing violence outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel downtown came on the air.

It showed a melee of blue-helmeted police and young people—from the tape, one could not call them demonstrators, because there was really no sign of anything as organized as a demonstration in sight. The police were running about everywhere, in and out of knots of youngsters, and clubbing and dragging them over to patrol wagons. On the accompanying sound track, one could hear a great deal of confused noise, yelling, boos, and an occasional bang, whether from the firing of tear gas grenades, the explosion of firecrackers, or some other cause, one could not tell. Over the videotape, Cronkite’s voice provided a commentary that was based partly on a description of the material that had been provided by CBS people on the scene of the disturbance and partly on what he was seeing of the tape on a monitor in front of him. “There seems to be a minister in trouble with the police,” he observed. “They’re manhandling him pretty severely… that cop certainly had his eye on a target”—this over a scene showing a policeman running right into part of a crowd and wildly clubbing and collaring a young man. (Chanting in the background of “Sieg Heil!”) “There seems to be a wounded man there, at that point.” And again: “The young lady [here, a shot of a girl, in great distress, being led away from the crowd] seems to be quite well dressed.” (This in an avuncular tone.)

The scenes, Cronkite said, had been videotaped about an hour previously and represented a situation that now had been restored to comparative calm. He reported that the National Guard had “advanced” into the lobby of the Conrad Hilton, and had cleared the lobby.

Over the intercom: “Dan Rather is with Paul O’Dwyer on the floor. Mr. O’Dwyer is going to say the police used unnecessary brutality on the floor and that real delegates to the convention have been thrown out because that’s the way the convention is being stage-managed. Do you want it?”

“Joe Benti up in the stands—he has information that people up there in the stands have been picking up credentials in the mayor’s office. We can’t do a thing about how it’s stacked for Humphrey up there. Are you interested?”

“Alioto is going to nominate Humphrey, and when the demonstration breaks out I suggest cutting to Benti and we can explain how this demonstration got organized.”

“Mike Wallace is back. He’s okay.”

Forty minutes after the first videotape of the violence outside the Conrad Hilton had been shown, Cronkite, on the air, made a brief introduction of a second section of videotape that had just arrived from downtown. “There has been a display of naked violence in the streets of Chicago,” Cronkite told the CBS audience before the film came on. But, he said, there had been no repetition of the worst of the previous violence; he went on to say that National Guardsmen had since reinforced five distinct lines of police that had pushed anti-war demonstrators half a block from the demonstration area outside the Hilton. Cronkite also reported, before the video tape went on, that “CBS News producer Phil Scheffler, a witness to that Hilton violence, said it seemed to be unprovoked on the part of the demonstrators; the police just charged the demonstrators, swinging at the crowd indiscriminately.”

The videotape, which had a narration by Burt Quint, showed, against a background of great noise and booing, and in the glaring artificial lights of the television network people, columns of National Guardsmen advancing north on Michigan Avenue with bayonet-tipped rifles, a shot of a machine-gun manned by a National Guardsman on top of a car, and other shots of Guardsmen and Chicago police pushing and herding people around.

These shots, I understood, had been made from a CBS mobile unit known as Flash Unit Number One, which had been stationed in Grant Park, directly across Michigan Avenue from the Conrad Hilton. Flash Unit Number One consists of a big, gray-painted truck with a platform on top of it for two television camera rigs, and, inside, a miniature control room manned by a producer, a director, a videotape-recording engineer and a couple of other technicians. Normally, it is used for live transmissions by microwave equipment, but during the Chicago convention, because of the telephone workers’ strike, it could be used only for producing videotape. The producer in charge of this Flash Unit, a big, gregarious man named Alvin Thaler, later told me that the first two sections of videotape concerning the disorders outside the Hilton that were shown on CBS that evening were taken from at least an hour of continuous electronic-camera photography by two cameramen on top of the truck, using four 1,000-watt floodlamps. As the pictures were monitored in the little control room inside the truck, the images were intercut sequentially, in whatever way seemed desirable to the unit director, David Roth, and compiled into one videotape recording. As the tape progressed, parts of it would be cut off, stuffed into a videotape box, and thrown out the back of the truck by Thaler to one of two motorcycle couriers who would dash off with it to CBS convention headquarters at the Amphitheatre. Flash Unit Number One had been in Grant Park since about dusk, and for about half an hour thereafter Roth, watching the monitors in front of him, had his attention focused on the police who were throwing people into a van at the corner of Balbo. Then, he told me, he suddenly saw something on one of the monitors that caused him to be momentarily disoriented; he saw on it a foreshortened shot of a big formation of helmeted troops marching along with rifles and bayonets. He told me that for a moment he imagined that the closed-circuit monitor he was looking at must have been feeding in an actual television broadcast, and that what he was seeing was part of some war movie. He assumed that both his cameras were pointed northward, at the disturbances at Balbo and Michigan Avenues, and sticking his head out of the truck in that direction, he saw no troops there. Still confused, he looked southward, and only then did he realize that one of his cameras was pointing south, and that there really were troops with bayonets and gas masks and machine guns and rifles, and jeeps with barbed wire screens in front, advancing north on Michigan Avenue.

During and since the convention, not only Mayor Daley but a number of other politicians have denounced television coverage of the disorders in downtown Chicago as biased and unfair to the Chicago police, who, they said, were subject to great provocation, which was not shown on television, by demonstrators. There were also allegations that television itself, with all its lights and paraphernalia, had had a provocative effect on the demonstrators and had increased the intensity of the clashes between them and the Chicago police. From where I sat on Wednesday evening in CBS Central Control at the Amphitheatre, I obviously could not be an eyewitness to the scenes in downtown Chicago. But I was highly interested in the circumstances under which CBS, like the other television networks, was able to cover the disorders, and this interest was based in part on what I had been hearing from CBS people, since well before the start of the convention, about the problems of coverage confronting them in Chicago.

In fact, I had talked to Robert Wussler about the subject as long ago as the beginning of December, 1967, when Wussler and fifteen other people assisting him had already been at work for several months on CBS convention-coverage plans. Wussler had been apprehensive about the choice of Chicago for the convention. He told me that the Democratic National Committee had had a subcommittee of ten people at work to recommend the most appropriate convention site, and that the subcommittee had had presentations from the mayors or other representatives of Miami Beach, Houston, and several other cities as well as Chicago. He said that after hearing these presentations the subcommittee had voted on its preferences and that of the ten votes cast eight had been for choosing Miami Beach as the convention site and two had been for Houston. Chicago got no votes. But in the end, he said, the recommendation was overturned. “I guess what it amounted to was that Lyndon Johnson and Richard Daley had ten votes between them on the committee,” Wussler told me. “Half a million dollars was raised by Daley as an inducement to bring the Democrats to his city, and Daley also made a pledge that no riots would occur in Chicago during the convention.” Wussler then had added, “I have great respect for Daley—he’s one of the best old-time mayors in the country. But I doubt that he can make good on that pledge. It could get pretty messy in Chicago.”

In April, I had talked again to Wussler, and he had still sounded worried about the likelihood of disturbances in Chicago during the convention, particularly since the CBS people had had a chance to observe the temper of the Chicago ghetto during their coverage of the rioting that had taken place there after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. And I had talked to him again a week or so before the beginning of the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach. By then, Wussler was deeply worried about another development, the strike of electrical workers in Chicago against the Illinois Bell Telephone Company, which began this past May, and which threatened (because telephone lines are almost inextricably involved in any full scale live television coverage of any event) to interfere with the ability of the networks to bring the Democratic convention to the home screen. As the Republican convention got under way in the first week of August, the ability of the networks to complete their live installations in Chicago, even if the electrical workers’ strike should be settled, looked very dubious. Because of the impasse in the telephone strike and the increasingly ominous signs that violence might erupt in Chicago, representatives of the Democratic National Committee considered briefly, before or during the Republican convention, changing the site of the Democratic convention to Miami Beach, where very elaborate live television installations existed at Convention Hall and throughout the city. In connection with this possibility, Richard Salant, the president of CBS News, told me, just before the Republican convention, that “suggestions, not so subtle, were made to us that since the networks would save money on any move of the Democratic convention to Miami Beach we ought to pay up money we would thereby be saving. We turned these suggestions down. Personally, I think network television is vulnerable enough as it is, considering, for example, what it’s done to sports, where it moves games from day to night, to have them take place in prime time, and where it arranges for guaranteed times out in football to get in a specified number of commercials, and so on.”

A week before the Democratic convention in Chicago I talked to Salant again. Early in July, Mayor Daley had made an accommodation with the striking local of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, under which the electrical workers agreed to lift their strike temporarily at the International Amphitheatre itself, but not elsewhere in Chicago, which meant that live network coverage of the convention would be confined strictly to the Amphitheatre and would not extend to the downtown hotels where the candidates and delegations would be staying. Nor would it be possible for television mobile units to operate, live, between remote locations and the Amphitheatre; the striking telephone workers claimed jurisdiction over the microwave relaying of televised images from these units. Salant was now plainly disturbed by what he considered to be the political implications of these restraints placed on television coverage of the convention. “Daley had enough muscle to obtain a strike moratorium at the Amphitheatre. Why couldn’t he have enough muscle to extend the moratorium to the hotels where the candidates were? Daley told our people that the only live microwave relay we would be permitted outside the hotel would be at O’Hare Airport, and that only if and when President Johnson arrived there. Why just Lyndon Johnson? When the strike moratorium was announced, Daley held a press conference, and someone there raised the question of why the delegation headquarters and the Conrad Hilton wouldn’t be covered live. Daley said that this wasn’t the candidates’ problem, it was TV’s problem. I attach considerable significance to this; nobody who is politically wise would give an answer like that, because he knows that no candidate can operate effectively unless he has full contact with the communications media. It has the effect of giving a great edge to the guy who’s ahead. I have the suspicion that the power structure here feels that it can so arrange things that network television can be excluded from those aspects of the convention that they’d just as soon we didn’t cover. They obviously don’t want us to cover any of the demonstrations live; I’ve had word that one of Daley’s aides considered writing a letter to the Federal Communications Commission asking it to send fifty observers to watch how the networks cover demonstrations, and to have these officials empowered to order us out if that should prove desirable.”

In an age when a boy in a ghetto riot who heaves a rock within view of a television camera can do it with a sense that he may be throwing the rock not just across a street but also into the living rooms of tens of millions of homes, the relationship of television cameras to what they are registering at scenes of civil disturbance involves serious problems of judgment. In general, in talking to CBS people before as well as during the Democratic convention in Chicago, I found them quite frank to acknowledge the possibility that the presence of a television crew at scenes where violence might break out might itself somehow help to trigger violence, or, where violence was already occurring, to exacerbate it. In fact, before the start of the convention, Salant called his executives together and briefed them on their manner of any covering of civil disorders that might take place in Chicago. He instructed them to keep all of their reports in reasonable context and to avoid giving publicity to people “desirous only of getting their faces on television by making inflammatory statements.” Further, he said, “We must in no circumstances… give reasonable ground for anybody to believe that we in any way instigated or contributed to civil disorder.” He told them to have their men avoid using lights when shooting pictures, since lights tended to attract crowds, and to obey police instructions instantly and without question. Camera crews were to be instructed that if they found, during any civil disturbance, that but for their presence the disorder would not be taking place, they should immediately cap the lenses of their cameras, regardless of what the crews from competing networks were doing.

As the convention got under way, I found the CBS people in Chicago expressing increasing dismay over what they felt was a deliberate policy on the part of the Daley administration to hamper television coverage of any civil disorders, of any demonstrations taking place within the city against the Johnson administration and American involvement in Viet Nam, of the discussions taking place at delegation headquarters in the downtown hotels, and of the convention itself. The Chicago police were reported to be taking a tough and uncooperative attitude toward television crews working outside the convention hall. The Department of Streets and Sanitation refused to give permits for the networks to park their mobile units on the streets outside the major hotels; when the CBS people attempted to rent space for their mobile units in parking lots adjacent to the hotels, they encountered an extraordinary reluctance on the part of the lot operators to let them have space, even at fees amounting to several hundred dollars a day. Alvin Thaler reported that parking space for mobile units in some places, such as service stations along a projected line of march of a demonstration scheduled for August 28, in several cases could not be obtained at any price mentioned, although usually the owners of such places are delighted to cooperate with television networks and to turn an easy dollar. At the Amphitheatre, the CBS people were informed that “for security reasons” they would not be allowed to put cameras in the windows at the front of the building to photograph any action going on outside; and even at the Conrad Hilton, where on the fifth floor CBS had set up a newsroom to cover the candidates’ and delegations’ headquarters, the head of the newsroom operation, Ed Fouhy, was warned by security people that the network would not be allowed to use the windows of its suite to photograph events outside—even to train its cameras on Grant Park opposite, where Yippies were expected to gather. At the convention itself, neither CBS nor any other network could obtain any assurance from the Democratic National Committee until the night before the convention as to how many cameras would be allowed on the floor during the proceedings. (In Miami Beach, the Republicans had let the networks know as far back as the beginning of June just how many floor passes they would be allotted.) When at the last moment the decision on floor coverage was made in Chicago, CBS, like the other networks, was allowed passes for only two television correspondents and one miniature portable television camera; the network had been asking for passes for four correspondents and two cameras. (In Miami Beach, CBS had been allowed passes for four correspondents and two miniature cameras.) Eventually, and after many protests, accommodations were made with the authorities over some of these difficulties—for example, parking and the number of floor correspondents, which was increased to four, with the other correspondents getting on to the convention floor with messenger passes. But the CBS people, who in Miami Beach had had the run of the place and had enjoyed quite full cooperation from the Republican National Committee, the city administration, and the police, and had even had a minimum of difficulty with local unions, continued to feel, in Chicago, a sense of official reluctance and resentment. As for the convention itself, the atmosphere was an almost palpably oppressive one, with barbed wire entanglements, masses of helmeted police around the Amphitheatre, the Potemkin-village quality of the approaches through the stockyard slum areas—along which, on block after block, the Daley administration had erected redwood screens that concealed rubble-strewn lots and dingy entrances—the countless security checkpoints, the magnetically coded passes, and the swarms of unrelentingly suspicious plainclothesmen with hips and armpits bulging with weapons. With all this around them, the CBS people, who at the Republican convention had mounted a most elaborate live communications system between Republican headquarters, the delegation hotels, and Convention Hall, were now reduced to keeping in touch with their newsroom downtown by having secretaries continuously dialing the switchboard at the Conrad Hilton Hotel in the hope of getting a line that wasn’t busy, so that they could then be connected with the newsroom. On Tuesday, during the CBS Evening News, I had seen on the screen pictures relayed by satellite from three different continents, showing in turn scenes of the Russian occupation of Prague, the visit of Pope Paul to Colombia, and the results of Viet Cong rocket attacks on Saigon. From Chicago that same day, a satellite was relaying to Europe with equal efficiency television coverage of the Democratic convention. The big communication problem seemed to be making a telephone call from the Amphitheatre to a downtown hotel.

All these frustrations had to be coped with by people who had been working for eighteen or twenty hours a day, seven days a week, during the frantic preparatory period at the Amphitheatre. (Casey Davidson remarked to me that the people in his Remote Control unit had “volunteered for service in Czechoslovakia to a man.”) But the CBS men had their first really ominous signs of deteriorating relations between the Daley administration and the news media when, on the first night of the convention, at Lincoln Park, Chicago police began beating Yippies and also began to pay physical attention to television cameramen, still photographers, and reporters. One of the cameramen was Delos Hall, of CBS, who had been filming a crowd of young people who were being dispersed on Division Street near Wells by three policemen. “As far as I knew, three policemen were doing a fine job of dispersing the crowd,” he later reported. “Then, apparently, a larger group [of police] arrived, running from behind me toward the marchers. Then, without warning, one of the first officers to pass me swung at me and hit me on the forehead with his nightstick, knocking me to the ground. When I got up I continued filming and was pushed and shoved from policeman to policeman, especially when they saw me filming them clubbing or arresting marchers.” The clubbing of Hall was witnessed by Charles Boyer, a cameraman for WBBM, the CBS-owned television station in Chicago, who himself had just been beaten by police, and who, at about the same time as he saw Hall being assaulted, saw police attack a third television cameraman, James Strickland of NBC, who is a Negro. Strickland, he said, kept telling two officers who grabbed him that he was from NBC, “but they kept telling him, ‘You black mother——, we’ll kill you before the night is over.’ He got rapped in the mouth a couple of times and I understand he had a tooth busted off.” Besides the scores of young demonstrators and onlookers attacked, about twenty-five newsmen were beaten, maced, or otherwise severely harassed by the police in or around Lincoln Park that night.

On Wednesday night outside the Conrad Hilton, and in the neighboring streets, newsmen were beaten during the disorders, but the extent of their injuries appears to have been minor compared with those inflicted on other people that night. So far as I know, no CBS people were among those injured. By no means all the CBS network cameramen were sympathetic to the demonstrators. Most of them just aren’t made that way; they are people who may earn tens of thousands of dollars a year, have comfortable homes in the suburbs, belong to a craft union that sees to it that they fly first class while the producers of the programs they are shooting are obliged by the network to fly economy. Some of them consider the demonstrators outside the Hilton to have used considerable provocation, ranging from the free use of obscenities to the throwing of bottles at the police. “The Yippies deserved the cops, and the cops deserved the Yippies,” one of the cameramen said later in a typical comment. Yet if the cameramen witnessed physical provocations by demonstrators outside the Hilton, they seem, in spite of their generally neutral or even unsympathetic attitude, not to have been able to include shots of these acts in their videotapes or film. (Nor, for that matter, were the undercover police cameramen who provided material for the television film which was later put out by the Daley administration to justify the actions of its police in Chicago.)

On Wednesday night, CBS televised, in addition to the two tapes shot by Thaler’s unit that I have referred to, two other sequences of the disorders along Michigan Avenue. The first of these, which was run just before 1 a.m., EST, when the nominating speeches were still going on in the Amphitheatre, was a videotape recording of a film that largely duplicated the scenes shown earlier of arrests and clubbings around the patrol wagons outside the Conrad Hilton. The second sequence was run after the formal close of the Wednesday convention proceedings and the nomination of Hubert Humphrey as the Democratic Presidential candidate. This sequence, which went on the air almost without narration and with only the comment by Cronkite that the pictures seemed to speak for themselves, showed dramatically the predicament of a woman who had picked up a couple of demonstrators in her car at a roadblock at about 5 p.m. (These demonstrators, I learned later, were casualties of tear-gassings by the National Guard at Michigan Avenue and Congress Street.) As the woman gave the demonstrators a lift, and attempted to drive on, National Guardsmen in gas masks stopped her with guns and bayonets; one guardsınan thrust a big barreled tear-gas grenade launcher through the driver’s window and aimed it at her; another, with his rifle pointed downward, motioned as though to bayonet the car’s right front tire. (A cry on the sound track, from a bystander: “Come on, CBS, show it all! Show the world!”) Then another guardsman discharged tear gas at the car. The sequence, which came through on the screen as though enacted in slow motion, lasted some four minutes.

Much later on, after the Democratic convention was over, and when the initial reaction of shock in the press had abated and an uproar of criticism by Congressmen of the television networks’ coverage of the violence was breaking out, I asked for and obtained an opportunity to take another look at videotapes of these sequences. And it did seem to me that there was a considerable difference between reports of the disorders that I had been reading in the press and the sequences I was seeing on the television screen. The television sequences that CBS ran as its version of events on Wednesday night showed far less violence, and far less detail of what took place outside the Conrad Hilton, than reports that appeared in the daily press or those that were compiled by, say, Time or Newsweek. And even the still photographers, it seemed to me, provided far more detailed documentation of the violence than the CBS sequences that appeared on television did. The only real violence that CBS documented that night was the clubbing of a few young people as they were being dragged and thrown into the patrol wagons, and that action was later repeated, in a different version, in lieu of other original material from the scene. What the CBS shots televised on Wednesday night did not catch and that press reporters on the scene caught and described in detail included: first, the police charge at Balbo and Michigan Avenues upon a crowd through which, a short time before, a four-mule train of Poor People’s Marchers led by the Reverend Ralph Abernathy had been allowed southward; second, a rampage of motorcycle police who drove over the curb on the east side of Michigan and into the crowd gathered on the sidewalk; third, a further charge of police from west on Balbo upon a crowd of onlookers and demonstrators hemmed in around the northeast corner of the Hilton; fourth, the specific acts of police clubbing of individuals among the trapped mass of onlookers and demonstrators; fifth, the panicking of the pushed and beaten crowd (the southerly fringe of which was even assaulted with police sawhorses used as battering rams) so that it backed up against the plate glass windows of the Haymarket Lounge, at the northeast corner of the Hilton, causing the window to break, and people to fall back, some bleeding badly, through the jagged hole to the inside; sixth, the police clubbing, inside the Haymarket, of those who had fallen in, as well as bystanders; seventh, further acts of police clubbing, in the main lobby of the hotel, of young people, some of whom had taken refuge there from the action on the street; eighth, a further charge by the police, with another mass assault with nightsticks on another crowd of onlookers—many of them delegates’ wives—on the sidewalk a block north of Balbo at Harrison, and similar indiscriminate assaults on crowds on the side streets of Michigan. In the press, all of this and much more, in detail, was spread over column after column and shown in scores of still pictures. Yet CBS could not show this detail even with a total of something like six television cameras and three film cameras trained on the scene outside the Hilton and north along Michigan Avenue. And when the violence first broke out, the area in front of the Hilton, brilliantly lighted by the television network people, looked, in the words of one CBS man, “like a movie set.”

Why the discrepancy in detail between media? I believe part of the answer is that individual reporters and photographers possess much greater mobility in such scenes of disorder than do television crews, burdened with cameras, lights, and sound equipment. (And when the television crews are working with electronic rather than film cameras, their equipment usually is tied by coaxial umbilical cord to a parent truck carrying recording and relaying equipment.) Television people usually need room in which to operate; they work only with difficulty in crowds. The electronic cameras on top of a mobile television unit have an elevated view and are equipped with lenses that can zoom in or out of scenes in a telescopic manner, and this is a great advantage in certain situations, but again not necessarily in crowds, since an overhead telescopic show of part of a dense crowd usually gives such a foreshortened effect that action taking place within the crowd is hard to distinguish especially during a scuffle, when some of the people involved may be on the ground and out of sight. (A still photographer, using a miniature camera and a wide angle lens, can work very close to his subject and encompass a great deal of action in his field of view.) Further, a press reporter is in a better position to isolate and record the relationship between a particular action and reaction in a crowd or confrontation; when he sees, for example, a provocation such as a taunt that is followed by some reaction on the part of police, he connects the two in his account; but the television cameraman, unless he trains his lens continuously on one spot, is hard put to record the instant when provocation draws police action. He may record the police reaction, but his camera has no memory of what happened before he pressed the camera trigger; it has no capacity for generalization, and the cameraman himself is no writer; he usually hands his film on to a courier with a hasty note about the subject matter. I mention this difficulty because often, in disorders, isolated provocations such as stone throwing occur so quickly that only a cameraman with the quickest reflexes could record them. I was told later by CBS people on the scene that some missiles such as beer bottles were thrown at the police outside the Hilton after the police charged into the crowd. But in the CBS shots shown on the air I could see no flying objects other than young people who were being thrown into patrol wagons.

But what seems to have interfered most with the ability of CBS to televise in detail the disorders outside the Hilton on Wednesday night was the lack of light. The very conspicuousness and drawing power of the television cameras, which, critics say, attracts trouble within camera range, also attracts trouble for the television crews themselves, and it did so, especially in Chicago. Thus, about fifteen minutes after the violence first broke out outside the Hilton, the array of television lights on the second floor of the Hilton that was trained on the area in front of the hotel suddenly went out. This represented nearly all the illumination that had been used by the networks (on a pool basis, with CBS in charge of the pool) to televise the demonstrations and disorders up to that time. When the lights went out, Walter Urban, a CBS man who was in charge of the pooled lighting arrangements, heard a rumor that the cause of the blackout was the police. He went down to the second floor with another CBS man, James L. Clevenger, who had been asked by Ed Fouhy, the chief of the CBS newsroom at the hotel, to get the lights back on. The two men found that the lighting cables had been disconnected. Urban reconnected the cables and turned the lights on again. They had only been on two or three minutes when, according to Clevenger’s account, “A policeman wearing a helmet arrived and barreled by me and started pulling the lighting cables. I told him to stop and suggested that he come to the fifth floor and talk to Fouhy. He told me to shut up. I told him he could not pull these cables. He turned, put me up against the wall, waved his nightstick at my nose, and said he was giving the orders. I said, ‘Yes, sir.’ The lights went out.”

Then, according to Clevenger, another policeman, wearing a soft hat, arrived on the scene, was asked pointedly by the helmeted policeman if he had his gun and nightstick with him and told him to guard the disconnected lighting cables and to see that they stayed disconnected.

At about the time of the first outbreak of violence outside the Hilton, Herbert Schwartz, a CBS film cameraman, was standing with his crew, an electrician and a sound man, on Balbo Avenue next to the Hilton Hotel, waiting to film Senator McGovern when the senator emerged from the hotel to travel to the Amphitheatre. Schwartz saw a large contingent of police marching east along Balbo toward Michigan Avenue. Schwartz and his men grabbed their portable sound equipment, walked toward Michigan Avenue ahead of the police, and under the marquee of the Hilton on Balbo began to film the advance of the police. Just before Schwartz started his camera, his electrician, Tim McGann, turned on his portable light to illuminate the scene. “Suddenly, a white-shirted police officer charged at [McGann],” Schwartz reported, and he said the officer then yanked the electrical cord from the battery pack the electrician was carrying. According to McGann, he was then pushed back so that he fell against another officer, and then to the sidewalk, and as McGann was falling the second officer hit him on the side of his face with the back of his hand. The electrician never again saw his lamp. All three men wore prominent CBS identification badges, along with Amphitheatre press credentials, which they wore around their necks. Schwartz and his sound man then were pushed by police with nightsticks into a crowd of onlookers and protesters on the corner of Michigan and Balbo, and according to Schwartz the two narrowly escaped being shoved through the windows of the Haymarket, but they managed to get out of the melee by shouting loudly for a police lieutenant who was nearby, thus momentarily distracting the attention of the police who were pushing them against the plate glass. (Schwartz and his sound man then went on to film some of the arrests being made, and they were not further molested. I don’t want to convey the impression that the rough treatment they received that night applied to all CBS people on the scene of the disorders; the attitude of the police toward them, by the accounts I have heard, varied from officer to officer and from one incident to another.)

The charge of the police on the crowd near the Haymarket Lounge was observed by a cameraman on top of another CBS mobile unit stationed near the corner of Balbo and Michigan, and the producer in charge of the unit, David Fox, instructed his men to train their cameras on the action. But the unit possessed no lights other than those from the hotel, and since the amount of light shining on the scene was very limited, the unit was unable to get a usable record of this incident. When Fox, sitting before a monitor inside the unit, had a chance to judge the quality of the violence he saw on the screen, he decided, on the basis of instructions issued by Salant not to endanger his men, that the situation might get much worse, and he ordered his men to pull out after the lights from the Hilton were turned off.

At about this time, Ed Fouhy, in the CBS newsroom on the fifth floor of the Hilton, decided that in view of the peremptory disconnecting of the networks’ lights by the police he ought to have Urban turn on a limited number of lights in the newsroom and rig them in the windows of the fifth floor CBS suite so that CBS electronic cameras on the floor could record at least part of the scene outside. But as soon as Urban did so a fuse blew and all power in the newsroom was lost. After some delay the fuse was replaced, and the lights were used for a while, but a police officer turned up and requested that they be turned off. Fouhy told me afterward that he had them turned off. (Much later that night, when the Chicago police outside the Hilton were replaced by National Guardsmen, these fifth floor lights were turned on again without objection, Fouhy said.)

When Fox’s unit left the area of Michigan and Balbo, Alvin Thaler, across the street from the Hilton on the Grant Park side of Michigan Avenue, continued recording on videotape what his electronic cameras were picking up with the 4,000 watt lights mounted on Flash Unit Number One, but after a while Thaler was told by a police officer to put his lights out. He did so. Some time later, when action broke out on the edge of Grant Park that he felt he ought to be recording, he turned his lights on for a brief period, and then he, too, gave the order for his unit to leave the area. Thaler strongly believes, he told me, that “whenever we put our lights on, we reduced the amount of violence in front of us. You have to realize that cops are far less eager to break heads right out there in front of the TV cameras than they might be somewhere back there in the dark.” James Fusca, who was working during the convention at the CBS news desk, was present when the police drove the demonstrators north on Michigan Avenue, well away from what television lights there were outside the Hilton, and he told me that in his opinion police action against demonstrators and onlookers was much more violent out of the lighted area than it was within it. The relationship between turned-on police and turned-on television lights is neatly illustrated by the observations of an assistant U.S. attorney that were reported to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. He was describing the progress of a melee that Wednesday night at State and Jackson:

I observed the police striking numerous individuals, perhaps 20 or 30, I saw three fall down and then overrun by the police. I observed two demonstrators who had multiple cuts on their heads. We assisted one who was in shock into a passer-by’s car.

A TV mobile truck appeared… and the police became noticeably more restrained, holding their clubs at waist level rather than in the air. As the truck disappeared … the head-clubbing tactics were resumed.

Police action in putting out lights when that suited their purposes was not confined to television floodlights, which the police later claimed had only served to heighten existing disorders; the police also broke or seized the strobe flash units belonging to many still cameramen. Since the duration of a stroboscopic flash averages something like one thousandth of a second, it can hardly be claimed to provide the kind of floodlighting likely to attract crowds. Nor was the dousing of lights by police even limited to the suppression of photographic activity in general. One CBS employee who was present when the police drove demonstrators north on Michigan has described how “One CTA [Chicago Transit Authority] bus had become stranded on Michigan and a number of demonstrators sought refuge from tear gas by climbing on the bus. The police followed them and blocked the exits from the bus while their associates beat those who were on the bus. To avoid being seen, the police turned the lights off. I heard a policeman shout, ‘You little long-haired queer. We’re going to stomp the —- out of you and all the other punks like you.’ Someone managed to get the bus lights on, and I had someone hold me up so that I could see what was happening on the inside. I observed demonstrators trying to squeeze themselves through the bus windows on the other side and I saw policemen beating one of the demonstrators all about the head and back and one of them had his foot in the kid’s groin.”

How was it, then, that with such limited coverage, and with all that the CBS people did not film or videotape of the more violent episodes in downtown Chicago on Wednesday night, that the sequences that were seen had such a remarkable effect on the audience? In terms of the communications process involved, it strikes me, after having viewed these sequences by themselves, that on Wednesday night the impression of violence in them was greatly heightened by the visual and aural context in which they were shown. And this was true in spite of the fact that the act of taping television shots always robs the audience, in some measure, of the unpredictability inherent in the originally occurring action, and the time lag tends to interrupt and dampen the immediate interactive process so remarkable in viewing live television. By the time the audience saw these tapes, it was already aware of the situation on which they were based, and understood, in effect, that the worst of what it was seeing was already over. It seems to me that the taped scenes appeared so violent because of something resembling what medical men call, in connection with the action of drugs, a potentiating effect—an unusual heightening of the action of some drugs in the presence of others.

How powerfully the interaction of even relatively inert images placed in immediate sequence can affect an audience was pointed out in the 1920’s by the Russian film director Pudovkin in his book On Film Technique:

Kuleshov and I made an interesting experiment. We took from some film or other several close-ups of the well-known Russian actor Mosjukhin. We chose close-ups which were static and which did not express any feeling at all—quiet close-ups. We joined these close-ups, which were all similar, with other bits of film in three different combinations. In the first combination the close-up of Mosjukhin was immediately followed by a shot of a plate of soup standing on a table. It was obvious and certain that Mosjukhin was looking at this soup. In the second combination the face of Mosjukhin was joined to shots showing a coffin in which lay a dead woman. In the third the close-up was followed by a shot of a little girl playing with a funny toy bear. When we showed the three combinations to an audience which had not been let into the secret the result was terrific. The public raved about the acting of the artist. They pointed out the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, were touched and moved by the deep sorrow with which he looked on the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he surveyed the girl at play.

In these cases, almost exactly the same neutral facial expression succeeded in conveying, through the process of visual potentiation, quite different and, in two of the sequences, very strong emotions. In the case of Chicago on Wednesday night, it seemed to me that the potentiating effect I have referred to was enhanced by the immediate juxtaposition of the tapes of the disorders in downtown Chicago with the supposedly more orderly scene of a nominating convention, which actually was exhibiting in its own way not dissimilar characteristics of irrationality and violence. It was as though, from widely separate sets of strands, someone were weaving cloth of unique pattern in front of one’s eyes.

Of the four tapes relating to the disorders downtown, the one showing the arrival of the National Guard and showing guardsmen pushing people back to the sidewalk near the Hilton probably displayed the least actual violence, although the sight of rows of bayoneted rifles advancing in front of the delegates’ hotel and the accompanying boos and crowd noise on the sound track certainly conveyed an air of considerable menace.