Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On March 8, seeing the writing on the wall, the roughly fifty journalists at Mother Jones’s offices, in San Francisco, began working from home. That decision was well ahead of the city, which didn’t issue a stay-at-home order in response to the spread of the novel coronavirus until two weeks later. But really, Mother Jones had been readying itself for disaster since mid-February.

“We need to prepare,” Mitch Grummon, the magazine’s chief financial officer, told Monika Bauerlin, the CEO, at the time. He knew their staff could end up working remotely for months.

During the weeks leading up to the work-from-home orders, Grummon began to check that all Mother Jones employees had adequate internet connections at home. He took care of some long-standing problems, updating invoicing systems that hadn’t been digitized and working out vendor management issues. Even if he were overreacting, Grummon figured, taking these measures to address contingencies would come in handy at some point—in the event of, say, an earthquake or a fire.

ICYMI: The road to making small-town news more inclusive

Grummon says it’s in his nature—and, to some extent, his job description—to envision the worst-case scenario. As he sees it, low-probability events are generally only low-probability in the short term. (His example: Wimbledon paid $34 million in pandemic insurance over the past seventeen years, only to cash in on a $141 million claim this year, after it was forced to cancel its summer tournament.) “These are things that will happen eventually,” he says.

In California, worst-case scenarios tend to come true. Last fall, a number of Mother Jones staffers had their electricity cut off due to fire-related power grid shutdowns that affected hundreds of thousands of homes. Schools closed, and many employees, unable to make arrangements for childcare, were forced to stay home. The Mother Jones team had to figure out how to put out a magazine in the midst of a partial shutdown—which only better prepared them for business as usual falling fully apart.

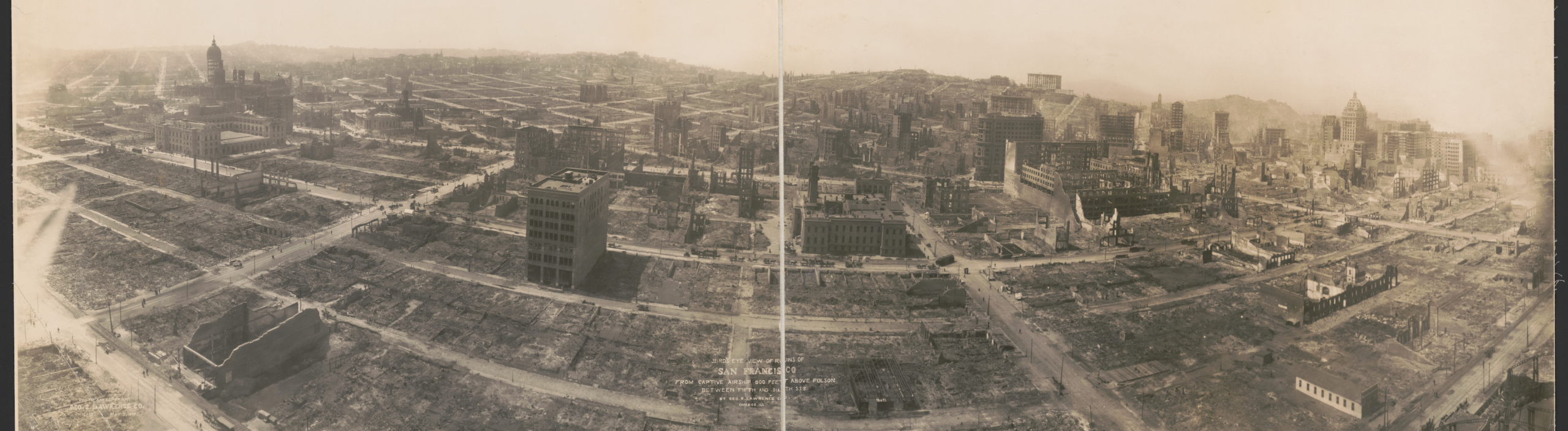

Newsrooms in California might thus have a leg up when it comes to operating in the midst of an emergency. The state is prone to sudden and devastating natural disasters. Audrey Cooper, editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, says her staff have been trained to go mobile on short notice. San Francisco has a history of catastrophic earthquakes, she points out, and the Chronicle building is more than a hundred years old.

In 2019, on the anniversary of the 1906 earthquake, the Chronicle held a work-from-home drill, putting out the day’s paper with the staff entirely remote. They held editorial meetings and filed and edited stories via online systems. That same fall, on the anniversary of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake—which destroyed the Bay Bridge, halted the World Series (which happened to be between baseball’s two Bay Area teams, the San Francisco Giants and Oakland Athletics, that year), and shut down the city for several days—they held another drill. By the time the novel coronavirus arrived, taking some newsrooms by surprise, the Chronicle knew how to publish remotely.

Most California newsrooms have some form of disaster plan at the ready. The Los Angeles Times keeps its printing presses separate from its main offices, in a downtown building equipped to withstand a major earthquake. The paper added a backup newsroom adjacent to the printing presses so that, in the event of the Big One, staffers could still turn out issues. Occasionally they issue a section of the paper from that emergency office, to ensure that the systems are working.

THE MOST CRITICAL QUESTION facing newsrooms is how to safely report the news out in the field.

Shelby Grad, metro editor at the LATimes, recalls that in the first days of the shutdown it was hard to know what guidelines to issue to reporters—there was little clarity on the precise risks presented by the virus. Ultimately, the Times developed a set of social-distancing and personal-protection guidelines to keep both source and reporter safe. Only reporters who opted in would be sent into the field, and management provided them with a mask, gloves, sanitizer, and goggles, where possible.

News outlets throughout the state had for years assembled go bags stocked with high-grade surgical masks, first aid kits, thermometers, hand sanitizer, gloves, and other protective equipment to assist in annual fire coverage. Grad went around the Times newsroom to cannibalize these into COVID-19 kits. He spent his weekends driving around to pick up equipment and drop it off at his reporters’ homes.

No degree of preparation, though, has made things easy, regardless of where the newsroom is based. “Co-ordinating a newsroom all of us together is Herculean and should be an Olympic sport imo,” Jessica Reed, features editor of the Guardian US, tweeted in March.

Editors and reporters say creativity suffers when colleagues are not in the same room. Even with the ease of remote communication, “it can be hard to replicate the organic creativity that happens when people converse, debate, and brainstorm in person,” says Reed, who normally works out of The Guardian’s New York offices but is now, along with the rest of the team, working from home.

Each morning, the up to forty journalists their East Coast team comprises log on to BlueJeans, a videoconferencing service, to plan the day’s coverage. It’s a lot of meetings, Reed admits—maybe too many—but “if any editor has found a way to reduce meetings right now, please, I will pay you a thousand dollars for your secret.”

Most disaster preparation is designed to provide short-term solutions to short-term disruptions, but this is no longer the circumstance in which any of us find ourselves. Even the California newsrooms have no long-term solutions for remote reporting, other than to grin and bear it.

“How do we build a resilient system that can’t get knocked down by one catastrophic event?” Grummon, of Mother Jones, wonders. All newsrooms need to ask themselves this question now, at a time when the public needs reliable journalism more than ever.

OP-ED: Covering science at dangerous speeds

This article has been updated.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.