Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

On July 17, the vast photo archives of Ebony and Jet magazines went up for auction, in an effort by the Johnson Publishing Company, which had recently declared bankruptcy, to settle its debts. A week later, the archive was sold to a consortium of four philanthropic foundations—the J. Paul Getty Trust, the Ford Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation—for just under $30 million. The haul included some of the most important visual documentation of the twentieth century Black experience. Likely the best-known photographs are those taken for Jet by David Jackson of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old Chicago boy who was lynched by two white men in Mississippi; many African Americans credit those images for inspiring their activist awakening. Also in the archive is Moneta Sleet Jr.’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of Coretta Scott King at the funeral of her slain husband, Martin Luther King Jr.; veiled and dressed in black, the stoic widow comforts her forlorn daughter Bernice, who has taken refuge in her lap. There are pictures of eminent stars, and of unknown families, amassing a collection that conveys Black humanity and loss.

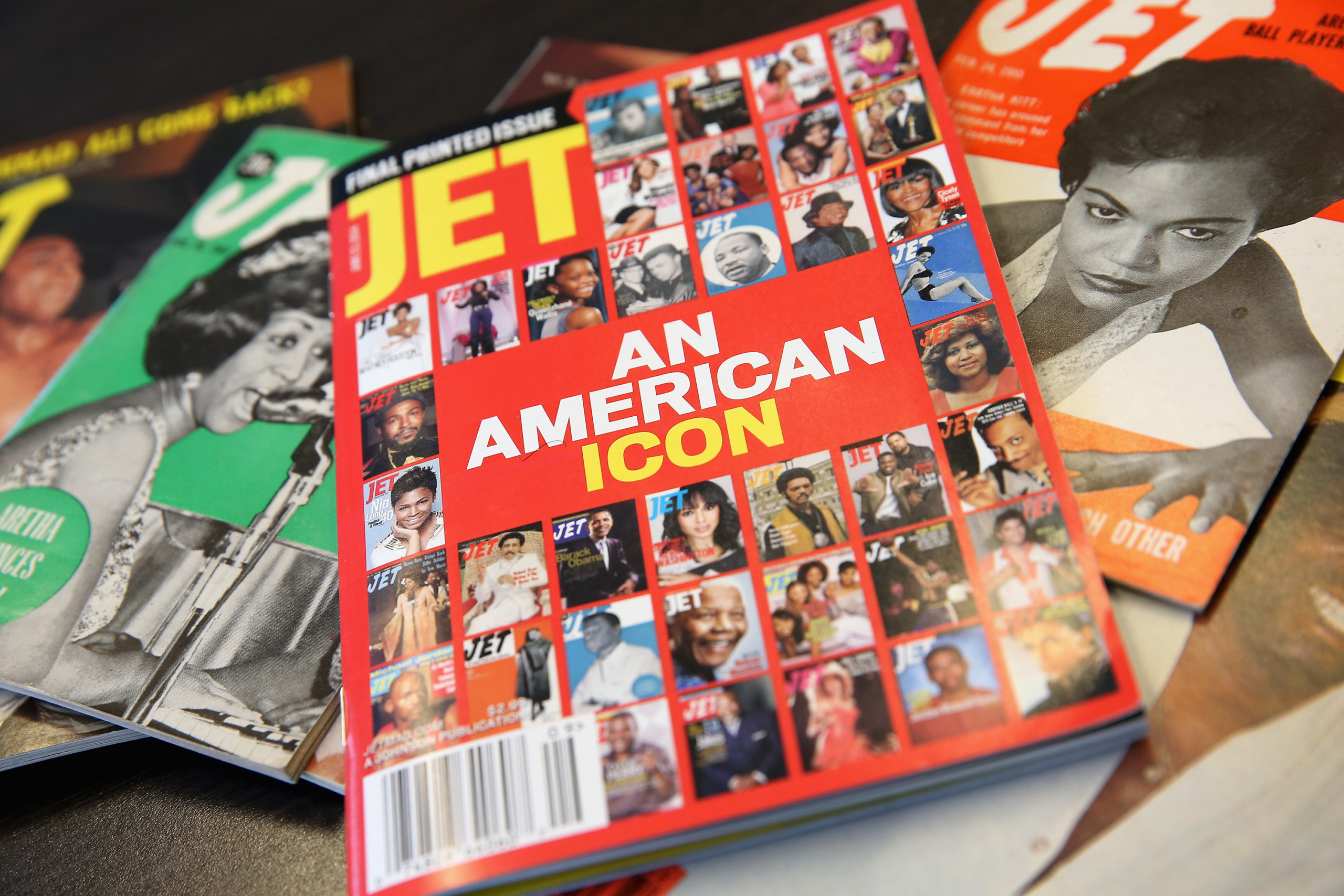

For anyone paying attention, the auction was not a surprise. It followed a decade of decline for a media company whose peak was in the past century. When the publisher, John H. Johnson, launched Ebony in 1945 and Jet in 1951, the two magazines filled a void in popular culture for stories that featured African Americans and portrayed them as they saw themselves. For much of the twentieth century, the Johnson Publishing Company (JPC) thrived. With the turn of the twenty-first century, however, competition with online media outfits grew daunting, and the company downsized to keep afloat.

ICYMI: The power and fragility of working in black media

In 2010, JPC sold its iconic headquarters building in Chicago; in 2016, company leaders sold Ebony and Jet to Clear View, an equity firm based in Texas. This left the company with few remaining assets, of which the archive, containing about 4 million images appraised at $46 million, was the only one of significant monetary value.

The appraisal, however high the dollar amount, cannot fully account for the tremendous historical and cultural value of this collection of photographs. When Johnson founded Ebony, he forever changed the popular representation of African Americans. Modeled after Life’s photojournalistic style, his magazine chronicled Black people and Black life through photo essays; photographs also filled the pages of Jet, a pocket-sized weekly digest, and other JPC publications that are now defunct: Tan, Hue, Copper Romance, and Black World. Beyond famous photographs of famous people, the images in these magazines illuminated lesser-known aspects of Black life. Wayne Miller’s photographs of female impersonators from the forties and Chicago’s drag balls of the fifties reveal a relatively unknown part of Black queer history. Photographs of mixed-raced couples and biracial families provide substantial record of resistance to legal, social, and brutal barriers to marriage and love. African Americans were depicted as politicians, professionals, homemakers, family men, scientists, artists and activists. Over seven decades, the JPC photographs represented African Americans as complex, ordinary, and extraordinary. The images are a visual counter to the popular racist imagery that has denigrated and dehumanized African Americans throughout United States history.

The scholarly value of this archive is as impressive as its cultural worth. In addition to about 100,000 photographs, it holds roughly 3.5 million negatives and slides, 160,000 contact sheets, and 9,000 audio-visual items. James Cuno, president of the Getty Trust, stated upon the sale’s finalization: “There is no greater repository of the modern African American experience.” It is little wonder, then, that in the weeks leading up to and throughout the bidding, historians (myself included) held our breath, fearing that the top bidder might be a private collector or a image-licensing corporation that might deny or monetize access to the archive.

Our fears had roots. The JPC photo archive first went up for sale in January 2015, because Desiree Rogers, the CEO, had determined that selling the photographs was necessary to grow the company. As a historian, I was struck by her characterization of the collection: “It’s just sitting here,” she said. I remember thinking, “Precisely, as a good archive should.” In her position, Rogers considered the collection to be a financial asset: “It’s almost like an African American Getty,” she said, comparing it to Getty Images.

Johnson Publishing never made its photograph collection widely available as an academic resource. The vast majority of the images were never public, and the company is known among scholars for being difficult. When I was working on a book about Black capitalist media makers, I spent years trying to access and acquire images; only after the company was sold did I obtain the permissions I sought, at a cost of thousands of dollars. (I would be remiss if I did not mention that despite all that, Vicki Wilson, the company archivist, was incredibly knowledgeable and helpful.) These challenges have stymied other research efforts, too, especially scholarship about the singular importance of JPC itself—once the largest and most powerful Black-owned outlet of communication in the world.

The paradox of this archive is that its contents, culturally priceless, were made to be sold on the market. Johnson was a businessman, and proudly so. “I wasn’t trying to make history,” he said. “I was trying to make money.” That the JPC photo archive ended up on the auction block is in keeping with its relationship to a capitalistic enterprise. The photographs were financially profitable precisely because they were of great emotional and political value to African Americans desperate to make sense of—and publicize—horrendous crimes against them.

We should also regard the JPC photo archive as an unparalleled repository of art to be studied and appreciated for photographic technique and aesthetics. Theaster Gates, an artist based in Chicago, highlights its contribution to photographic form in his exhibit The Black Image Corporation, which features the fashion photography of JPC’s Sleet and Issac Sutton.

When the JPC photo archive went up for auction, researchers feared the potential loss of stories, artistry, and knowledge crucial to understanding who we are and where we’ve been. When the archive’s new owners announced plans to donate its contents to historical and research institutions, including the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, we collectively exhaled. As a historian of African American history, business, and visual culture, I cannot help but worry about what will happen to JPC business records, too, in addition to the company’s photo archive. But we must recognize and accept our victories where we can.

ICYMI: Where have all the black digital publishers gone?

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.