Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

The corridors of the MAGNET center at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering buzzed with an excitement reminiscent of childhood science fairs. Booths decorated with monitors and gadgets lined the halls for The New York City Media Lab’s first-ever Fake News Horror Show, held June 7 and 8. The event, equal parts lecture series, workshop, and art show, had attracted a crowd that seemed as concerned with probing the problem of fake news and rampant misinformation on the internet as they were fascinated by the dystopian, gallows humor of it all. Think doomsday preppers, but media.

The show brought together computer scientists and technologists, counterterrorism experts and media researchers to probe the multi-headed beast that is fake news. There was a talk given by historian Matt Jones, a professor of contemporary civilization at Columbia University, that laid out the long history of misinformation—from propaganda to “perception management” (a defense term). Media Matters visiting fellow Melissa Ryan, who edits Ctrl Alt-Right Delete, a newsletter that tracks the alt right’s movements on the internet, hosted a panel spelling out the role activists play in helping to combat organized disinformation campaigns. J.D. Maddox, a consultant and counterterrorism expert, gave a talk laying out how the Global Engagement Center, a division of the Department of State, is handling the problem of misinformation and propaganda from terrorist groups and foreign governments around the world. Among others.

ICYMI: Cable news coverage of Trump’s summit with Kim Jong Un goes off the rails

The conference strongly demonstrated the tangled relationship technology, and all those who work to advance it, has with misinformation: From Facebook, an easy target of derision, to Adobe, whose development of an audio prototype that convincingly mimics speech fascinates and terrifies.

But reporters deep in the belly of the daily news cycle remained largely on the periphery of the conversation. Instead, the horror show kept technology and politics in its crosshairs. So where do journalists, the target of frequent attacks from the highest rungs of government in America and abroad, fit into that equation?

Often, they’re the unwitting victims. Several workshops held on Friday afternoon demonstrated the threat that “deep fake” photos and videos pose for news organizations and their consumers. Computer scientists Vishal Misra, a professor at Columbia University and Siwei Lyu, with SUNY Albany, offered a few solutions that news organizations and consumers alike can use: Signatures embedded into photos that could let editors and readers see what edits were made to an image and photography training that teaches people to study how the light hits multiple subjects in an image, revealing whether or not it has been spliced together. These tools, what Lyu called technology forensics, amount to a kind of visual fact-checking. Such an added step could prove crucial as news organizations become increasingly reliant on photos and video of breaking news uploaded to social media websites like Twitter and then broadcast nationwide, often without verification.

Despite the inevitable gloom of a conference focused on the worst parts of media, booths designed largely by students from various digital media programs combined art and engineering to criticize, poke fun at, and offer solutions for a way forward.

At one display, attendees played a mad libs style game to create their own fake news pulled from snippets of real articles published in The New York Times. Nouf Aljowaysir, a student with NYU’s interactive telecommunications program, designed a trio of partisan Twitter bots that users could feed information to, real or fake, and then watch them argue over it publicly on Twitter. Representatives from VettNews and Newscheck gave demos of browser apps intended to help readers discern the credibility of news sites.

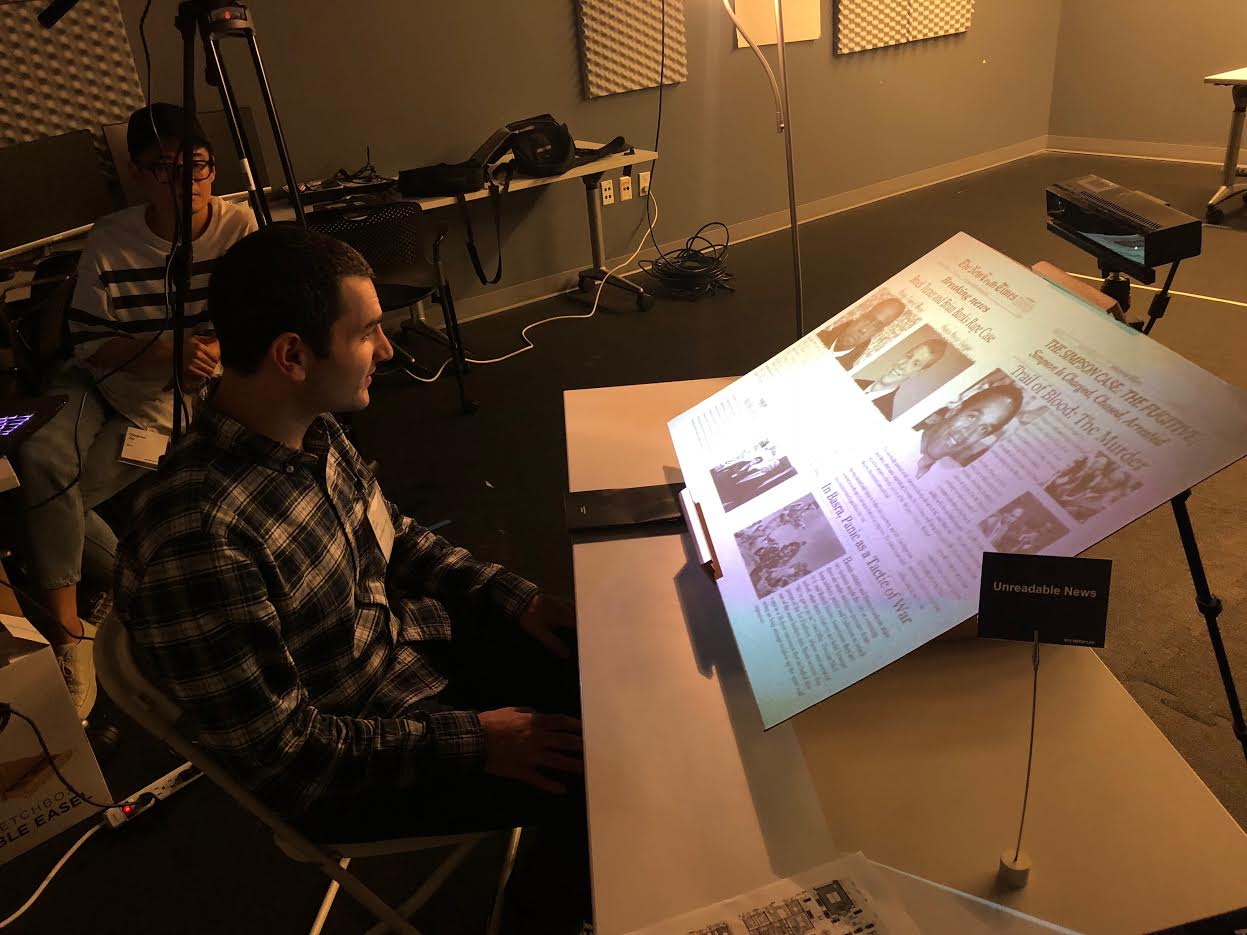

Ivy Huang, a student at NYU, offered commentary on how even real journalists at credible news outlets can distort the truth. Working with a classmate, she designed what looked like the typical front page of a newspaper, featuring real news stories on the Brock Turner rape trial, OJ Simpson, and Monica Lewinsky. But as you move your head from side to side, or closer to the display to read the text, it becomes distorted, physically blocking you from seeing the whole story. Words like “swimmer” and “Stanford” appear over the Turner story, and an image of the controversial 1994 cover image of Simpson in Time magazine covers the Simpson story. Near the Lewinsky story, viewers see just one phrase: “All her fault.”

Attendees at NYC Media Lab’s Fake News Horror Show view three news broadcasts, trying to identify which is fake news.

“All the content is reliable, but you still get the wrong news,” says Huang.

At a display designed by Utsav Chadha, Mithru Vigneshwara and Rushali Paratey, all recent NYU graduates, visitors were asked to look at a stream of broadcast news reports displayed on three monitors. The stories were arranged topically, and came from a variety of outlets including CNN, Fox News, MSNBC, and RT. Viewers were asked to study the stories and pick out the fake story. But here’s the catch: They were all stories that aired on real news stations. It’s the assumption that one of them hadn’t that was the real fake news.

“The real horror is not knowing what to believe,” says Chadha, who pointed out that one consequence of hysteria around fake news is the growing air of suspicion of credible news outlets that can, ironically, block consumers access to truthful information. “Let’s challenge everything about fake news by putting out real news,” he said.

The responsibility to solve the fake news problem likely involves multiple actors. But host Justin Hendrix, executive director of the NYC Media Lab, isn’t so sure working reporters should play an active role in this resistance.

“I’m not sure the extent to which it is the responsibility of journalists to fight misinformation,” he says. “[Their] role is to put good information out. The onus is on the technology companies.”

ICYMI: Looking for a journalism job? Here’s what hiring managers at WashPo, NPR and others are looking for

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.