Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

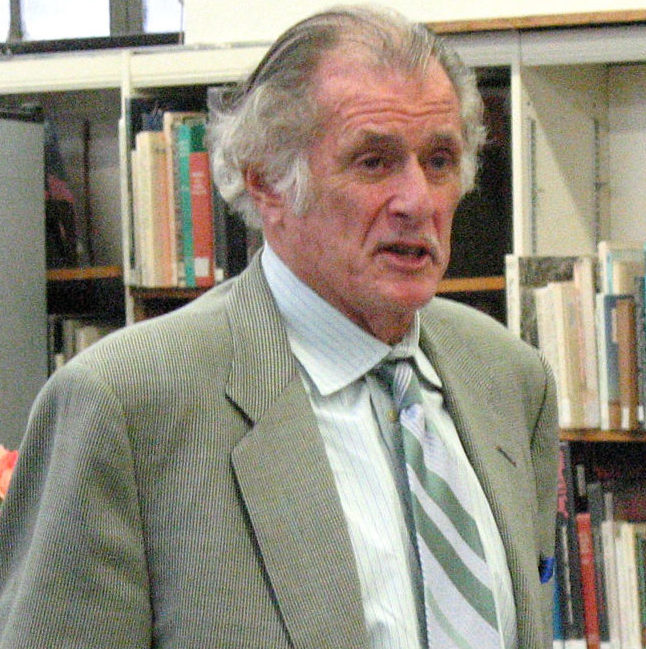

As a writer, there was nothing particularly innovative about Frank Deford. That sounds like a perfectly horrible thing to say about a man who just died, but it’s not. It’s the sort of compliment the former Sports Illustrated writer probably never sought—to be compared, as I’ll do now, with Gay Talese, John Updike, Norman Mailer, and even Hemingway and Faulkner. Deford didn’t set out to change journalism. He set out to write well, and to tell stories that, on the surface, appeared to be about sports.

By 1985, when Deford wrote “The Boxer and the Blonde,” an epic, novelistic love story about a beaten man and a beautiful woman, the literary heavyweights had already applied the tools of fiction—scenes, dialogue, narration—to bats, balls, and especially boxers. Talese on Joe DiMaggio. Updike on Ted Williams. Mailer on Muhammad Ali. Hemingway on bullfighting. Faulkner on the Kentucky Derby.

And then Deford on boxer Billy Conn:

The boxer and the blonde are together, downstairs in the club cellar. At some point, club cellars went out, and they became family rooms instead. This is, however, very definitely a club cellar. Why, the grandchildren of the boxer and the blonde could sleep soundly upstairs, clear through the big Christmas party they gave, when everybody came and stayed late and loud down here. The boxer and the blonde are sitting next to each other, laughing about the old times, about when they fell hopelessly in love almost half a century ago in New Jersey, at the beach. Down the Jersey shore is the way everyone in Pennsylvania says it. This club cellar is in Pittsburgh.

Deford had been writing for Sports Illustrated for nearly two decades when he published the Conn story, considered by many to be his masterpiece. He joined the magazine after graduating from Princeton, where he studied with British novelist Kingsley Amis. One day in class, Amis asked his students to name their three favorite writers. Deford’s answer: William Shakespeare, J.D. Salinger, and Red Smith. Amis had never heard of Smith, the New York Times sportswriter whose columns read like long prose poems.

“When Amis found out who this Red Smith was being linked with Shakespeare (I think everybody wrote down J.D. Salinger, so that didn’t count), he was titillated,” Deford later wrote. “And when he wrote a wry story for a British paper about his quaint experiences in New Jersey, prominent amongst those anecdotes was this one knee-slapper about how an especially rustic, provincial student had actually listed a sports hack as his favorite writer.”

But the joke was actually on Amis, that pretentious dullard.

By bringing his literary sensibilities to Sports Illustrated in the 1960s, Deford introduced great writing to middle class (and middlebrow) Americans far more successfully than Amis or other novelists of the day could have dreamed. Until then, literary sportswriting—and literary journalism in general—had been mostly limited to Esquire, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and other highbrow publications. In writing short stories that happened to be true for a magazine that put race cars on its cover, Deford became a literary man of the people, using the metaphor of sports to explore the struggles, mysteries, and absurdity of life.

Deford on Bobby Knight, the loudmouthed college basketball coach:

In the Indiana locker room before a game earlier this season, Knight was telling his players to concentrate on the important things. He said, “How many times I got to tell you? Don’t fight the rabbits. Because, boys, if you fight the rabbits, the elephants are going to kill you.” But the coach doesn’t listen to himself. He’s always chasing after the incidental; he’s still a prodigy in search of proportion. “There are too many rabbits around,” he says. “I know that. But it doesn’t do me any good. Instead of fighting the elephants, I just keep going after the rabbits.” And it’s the rabbits that are doing him in, ruining such a good thing.

Deford on Tony DeSpirito, a washed up jockey who died young:

This is what happens when you scale the top at age 16, and then can’t ever outdo it. Athletes get frozen in time. They get attached to a certain year. People say, “Oh, yeah, that was his year.” “That was Walt Dropo’s year.” “That was Dick Kazmaier’s year.” “Wasn’t that Tom Gola’s year?” Nobody ever says this about other people. Nobody once ever said that 1776 was Thomas Jefferson’s year. Maybe just athletes have years—and very few of them—usually just the kids. Willie Shoemaker never had a year. But 1952 was the late Tony DeSpirito’s year, and when we are all dead, the lot of us, when things are even, he will be able to say that he had the one thing very few others had. Maybe that is why nobody ever heard him rail at the misfortunes dealt him. At least he had a year in his hip pocket.

Deford would go on to become a TV and radio personality, for many years offering sports commentaries on NPR. He launched a short-lived newspaper in 1991 called The National Sports Daily, made up of sportswriters who wrote like him, though not as well. (In many ways, the National was Grantland before the internet.) But when the biographers come along to tell the story of Deford’s life, they should begin with the lack of pretension that undoubtedly helped make him one of the most important writers of his generation.

“When it began to occur to me, seven or eight years into the profession, that I was beginning to look like a lifer, I did spend agonizing hours at the bar, starting into another disappearing bourbon or talking over the quandary with other sportswriters of like conflict,” he wrote. “But, finally, I resolved the issue with myself: that I am a writer, and that incidentally I write mostly about sports, and what is important is to write well, the topic be damned.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.