Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

While Koch Industries snared headlines last fall for its partial acquisition of Time, Inc. (including Fortune, Sports Illustrated, and other holdings), the business empire’s nonprofit Koch Foundation made a smaller, little-noticed investment—granting $80,000 to the American Society of News Editors for its freedom of information hotline program.

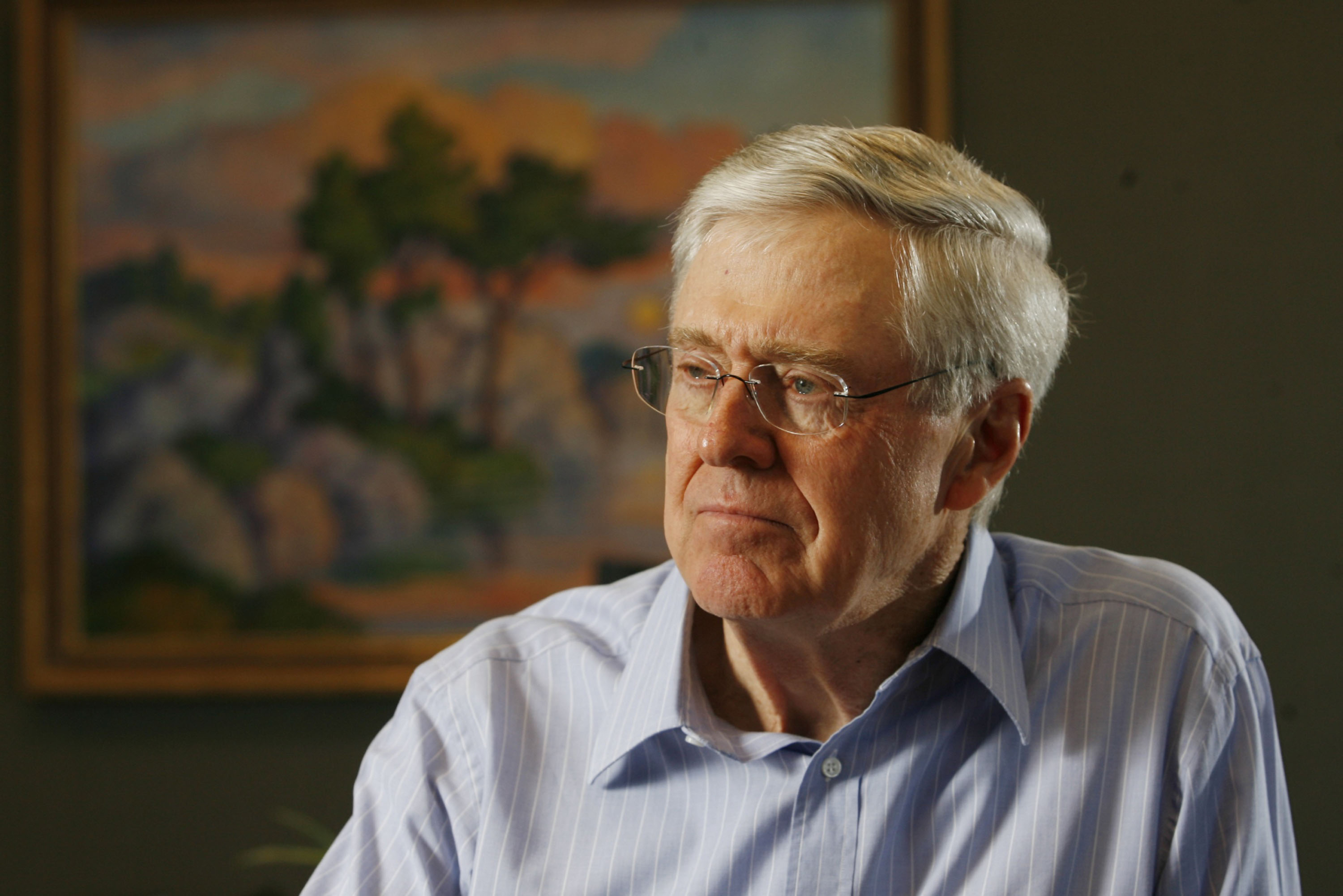

Historically media-shy, and famous for their efforts to discourage and discredit journalism critical of their business and political operations, the Kochs are now expanding their media holdings, while the family’s nonprofits ramp up donations to mainstream media institutions such as ASNE and the Poynter Institute, and underwrite programs for NPR and PBS.

ICYMI: A media controversy comes to an explosive conclusion

These two paths, by legally separate yet financially entwined Koch family institutions, have raised concerns about the Kochs’ larger effects on the media landscape, and on how they are viewed by the public and covered by the press.

The foundation’s grant to ASNE’s freedom of information program, and other Koch investments in government transparency, come on the heels of numerous attempts by the Koch brothers and their associates to discourage media coverage and disparage stories criticizing their political projects, such as their “dark money” campaign donations and climate denial campaigns.

In an ASNE news release, Charles Koch Foundation Director of Free Expression Sarah Ruger said, “The foundation supports many grantees committed to press freedom, including The Poynter Institute, the Newseum and Techdirt’s free speech initiative.

In June, the Poynter Institute and the Koch Foundation announced they were teaming up on a grant program for college journalists, “to encourage campus media to support and promote civil discourse around controversial topics.” College media organizations gaining grants will receive “up to $3,000 to spend on a reporting project or event that advances civil discourse on campus.”

Koch Foundation representatives highlighted their growing funding of both journalistic institutions and colleges, with more than 300 campus grants nationwide. As the foundation’s Director of University Relations John Hardin put it, the grants vary widely, exploring “civic and economic liberties that allow people to prosper.”

After this story published, Poynter Institute Vice President Kelly McBride wrote to CJR that when Poynter approached the Koch Foundation for funding, “we recognized that Koch Industries has not been friendly to journalists,” but maintained that the Koch Foundation is a separate organization. The Poynter Institute, McBride wrote, developed a clear policy to maintain independence from funders, but, “we’ve had to find new revenue in order to successfully fill our mission of elevating journalism in service of democracy.” The program funded by the Koch Foundation, she added, has been successful and they hope to expand it next year.

ICYMI: Not the best look for the New York Times…

Author and journalist Jane Mayer, who has investigated the Kochs for The New Yorker and her book, Dark Money, says the Kochs’ recent media philanthropy functions as “whitewashing” to clean up a corporate image stained by years of environmental pollution and what she calls “information pollution.”

“The Kochs have had terrible public relations issues,” says Mayer, “tarred by their reputation as one of America’s biggest polluters.” After years of bad press, “They have put a tremendous amount of money and energy into creating a new image, to win public favor through the press,” says Mayer. “I see this funding of institutions as part of their longstanding public relations effort. Those who take their money are doing them a great favor.”

Money helps expand hotline

According to longtime ASNE consultant Kevin Goldberg, who runs the freedom of information hotline, the project helps journalists contend with costly and contentious battles for public records, and occasionally with litigious story subjects. Journalists, he said, “increasingly find themselves without the financial wherewithal to fight legal battles…news media does not have the financial resources to defend themselves.”

Goldberg said the grant came about after conversations with the Koch Foundation, whose offices are near his, in Arlington, Virginia. “We’ve had these conversations for a while, and the next thing I know they were talking to Teri [Hayt],” ASNE’s executive director, about grant possibilities.

Hayt, a veteran journalist and editor who has led ASNE for the past three years, says the group has been “expanding our tent” and seeking new resources amid much financial belt-tightening. The Koch grant, which comprises the bulk of ASNE’s hotline budget, “really keeps us up and running…. They were very generous.”

In its first few years, the hotline has only seen “sporadic” use, a few calls each month, said Goldberg. “I’m kind of surprised it hasn’t been used as much as I thought.” Despite this, Hayt says, “We feel there’s a real need for this operation.”

ICYMI: Blockbuster White House book claims its first victim

In promotional materials announcing the grant, the Koch Foundation stated, “It’s no secret that news organizations are facing an increasingly hostile legal climate and that many do not have the available resources needed to protect and promote their legal rights.” Goldberg said his goal is to help ASNE members “avoid legal problems, better differentiate between true threats and frivolous attempts to bully, and proactively assert their right to information…An editor may come to me and say: ‘I know the story is going to be inflammatory and somebody might come after us. How worried should I be?’”

Journalists who have written about the Kochs say they have worried plenty about such threats.

Asked about the scope of the freedom of information project, Ruger, of the Koch Foundation, said it encompasses “promoting transparency and access to information to hold institutions accountable,” as well as “protecting journalists from attacks.” Trice Jacobson, the foundation’s director of communications strategy, added, “If it is possible for a lawyer or wealthy individual with a vendetta to sue someone out of existence, what does press freedom mean?”

But at least so far, the accountability focus is entirely on the public sector. When asked if the foundation is supporting any initiatives involving corporate accountability and transparency, Ruger responded, “not at this time.”

Private eyes and canceled stories

Consider Mayer’s experience after her longform New Yorker article probing the Koch business empire and its political impacts. Following her 2010 exposé on the Kochs, an operation with ties to the Koch brothers sought to discredit Mayer, according to numerous press accounts. “They went after me in a very personal way,” Mayer recounts. “They hired a private eye, and his firm spent months and months trying to dig up dirt on me.” The operation supplied dossiers to The New York Post and The Daily Caller alleging that Mayer engaged in plagiarism, a charge that was proven false.

“Naturally, you have to question their sincerity on freedom of the press,” reflects Mayer.

When award-winning Canadian journalist Bruce Livesey produced an investigative report on the Kochs in 2015, he soon found his story pulled from its scheduled release, and then himself out of a job. Just days before it was due to air, Livesey’s investigation, focusing on the Koch brothers’ oil and pipeline projects in Canada, was canceled by Global TV, based in Calgary near the epicenter of Canada’s oil industry.

While he couldn’t prove that the Koch brothers were behind his story’s cancellation (“At no point was expressed to me that the Koch industries had intervened,” he says), “the result was the same. Someone was fearful that some financial price would be paid for doing a critical story on the Kochs,” says Livesey.

Another indicator of the Koch effect: A number of sources contacted for this story declined to comment on the record about their experiences of backlash and intimidation.

In response to these accusations, the Koch Foundation’s Hardin said, “As far as we understand it, those accusations are not true.” Asked specifically about the Koch brothers climate denial campaigns, which journalists have criticized for denying verified scientific facts, Hardin said, “As far as we understand, we don’t know of any of that happening.”

Ed Wasserman, dean of UC Berkeley’s School of Journalism, sees a contradiction between intimidating reporters and promoting freedom of information. “Is intimidating reporters inconsistent with freedom of information? Of course it is… From the point of view of what I consider freedom of information, they’re total hypocrites for giving this grant.”

Asked about contradictions between the freedom of information grant and media suppression efforts by Koch-connected operations, Goldberg responded, “They’ve come to this with a purity of motive. They want free speech. They have no control over the Hotline, no control over my message….We are working with a 501(c)(3), that’s all. We only work with the Koch Foundation. I’ve never met the Koch brothers.”

When confronted with these criticisms, Koch Foundation representatives insisted on the separation between the nonprofit and the Koch brothers business and politics. Hardin said, “We can’t speak to what Koch industries is doing, we are the foundation.” Jacobson added, “We are a separate organization.”

However, Koch Foundation tax returns make clear that the nonprofit foundation and the for-profit Koch industries, which has aggressively pushed to expand its media holdings and conservative political impact, are financial bedfellows. Charles Koch sits on the board of both, and is the major donor financing the nonprofit foundation.

Strikingly, as the Koch brothers have expanded their public political profile, the nonprofit foundation has ballooned its resources and reach. In 2011, the foundation reported a total revenue of $6.1 million—in the following year, revenue jumped to $71 million, then $181 million by 2013. The bulk of the foundation’s growth can be charted to rising donations from the Koch industries business empire.

Invisible strings attached?

Critics say the integral relationship between the Kochs’ businesses and foundations creates a “symbiosis,” as Mayer puts it. “My concern as a working reporter who respects these institutions, is that the funders are trying to buy respectability, and maybe soften coverage of themselves. It’s really hard to bite the hand that feeds you.”

Wasserman adds, “I would speculate they surmise that the more money they give to media, the softer the coverage of them will be… In every newsroom funded by the Kochs, there will be a question about how coverage influences their funding… It will give journalists and newsrooms pause. They know, no matter what lipservice the Kochs pay, they are the ones writing the checks.”

Beyond his own experience, Livesey is concerned about journalistic institutions accepting money from the Kochs, who, he says, “are in the business of climate denial, denying what is factually true. When you have a family whose history is denying facts, and they are investing in journalism outfits whose business is in facts, it’s very disturbing. They should not be taking their money.”

Both ASNE and Poynter approached the Koch Foundation to initiate the grants, according to Jacobson. Asked for a copy of the grants, she said there is no memo of understanding or other formal document for either grant. McBride confirmed this to CJR after publication.

Hayt, of ASNE, says the Koch grant came after “robust” discussion among the board and staff, including conversation about the Kochs’ history. “The whole thing about their political action committees and not being very transparent, that came up. We are hoping that will change in the future.” Asked about the Koch operations’ efforts to stifle media coverage, Hayt responded, “I can’t condone any bullying of journalists, but I think they are reaching out. We are hoping that our association with them leads to a more positive environment.”

Disclosure: Here’s a list of CJR’s major funders.

This article has been updated to reflect comments from the Poynter Institute’s Kelly McBride after publication, and the fact that Charles Koch, personally, is the major donor to the Koch Foundation. In addition, a previous version said Bruce Livesey produced a story on the Kochs in 2014. He did so in 2015.

TRENDING: The real reason why journalists hate Michael Wolff’s White House book

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.