Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Meredith Kopit Levien, who was named the new CEO of the New York Times last week, has six million subscribers, almost $700 million in cash in the bank, and a singular insight that underpins the Times’ path forward: the average number of news subscriptions a news subscriber will have is one.

Local publishers may not believe that they are competing with the Times, but the Times believes it is competing with them. Its rich-get-richer dynamic increasingly provides all the news that’s fit to subscribe to, while publishers both national and local fall further behind. Competing with the energized leadership of a dominant and implacable Times will require leveraging networks, rethinking how content works in a paywalled universe, and unlearning some of the lessons of the open internet.

There’s one slot…

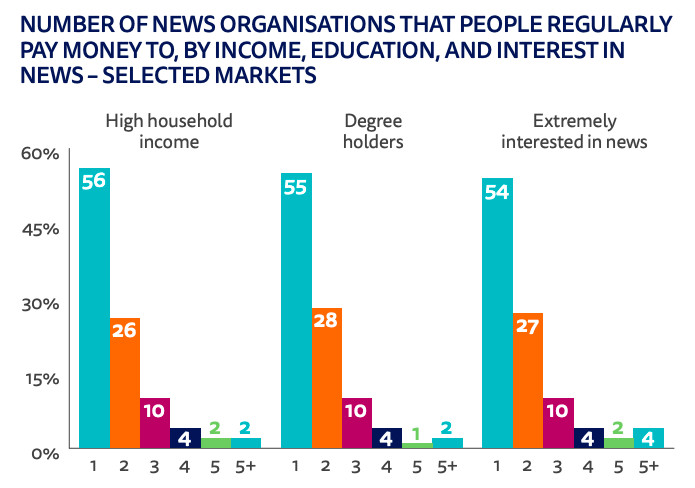

A 2019 study from Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism found that the vast majority of news subscribers in thirty-eight countries “have ONE online [news] subscription.” Even when taking into account people most likely to have multiple subscriptions, the majority still have just one subscription and four out of five have no more than two. The study was repeated and published in June, with few changes.

Credit: Digital News Report 2019, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Internal research at Google produced similar findings: the average number of subscriptions a news subscriber will have is just over one. Skeptics point out that local news offers a vastly different service from national outlets like the Times. That is both true and irrelevant. What matters is that for consumers choosing a news subscription there’s one slot for which both qualify. Fortnite provides a dramatically different service from Netflix, but you can be sure that Reed Hastings considers it a competitor. In 2019, Hastings noted that “We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO.” News organizations that look at their internal subscriber surveys and see a healthy space for two subscriptions are falling victim to survivor bias. They’re not surveying subscription candidates in general, but the small cohort of people who have shown unusual behavior already, in merely having a local digital news subscription.

THE MEDIA TODAY: The tech titans go (virtually) to Washington

More than any other publisher, the Times has recognized the market dynamic it is in. If the average number of news subscriptions remains one and the shareholders of the Times continue to demand growth, conflict with other publishers is inevitable. Luckily for the Times, it often finds itself in the best kind of fight: one in which only one side realizes a fight is going on.

The NYTs v. everyone

Here’s the Times in 2003, from its annual shareholders’ letter: “Our long-term strategy is to operate the leading news and advertising media in each of the markets in which we compete—both nationally and locally. The centerpiece of this strategy is extending the reach of the New York Times’s high-quality journalism into homes and businesses in every city, town, village and hamlet of this country.”

Here’s Jodi Rudoren, the assistant managing editor of the Times, speaking to Nieman Lab in 2018: “One of the things we always talk about is our cocktail of content—that is, what mix of New York Times stuff is going to make somebody, particularly somebody far away, or somebody who doesn’t feel today the Times is for them right now, think that this is totally relevant for me, and I want to have a relationship with that news organization?… Then, when we’re able to connect the global and local, it’s very powerful for people”

Here’s the Times in 2020: it added 587,000 new subscribers in the first quarter. That’s almost three times the number of total subscribers to the Los Angeles Times. It’s more than 70 percent of the total cumulative subscribers to Gannett’s 260 media properties. The New York Times has more digital subscribers in Dallas–Fort Worth than the Dallas Morning News, more digital subscribers in Seattle than the Seattle Times, more digital subscribers in California than the LA Times or the San Francisco Chronicle.

Again, there is one slot—and the Times wants it “in every city, town, village and hamlet of this country.” Local is a subscription cohort to be mapped and acquired, in the same way as Canadians or conservatives. This presents a problem for publishers who have attempted to replicate part of the Times’ strategy, but not all of it. They’ve successfully focused on differentiated homegrown content, hoping to drive brand loyalty and affinity. In many cases that has led to dramatic improvements in the quality of news produced at the local level. However, the other, crucial, aspect of the Times’ strategy is publishing a breadth of content able to capture sufficient attention share to make a subscription valuable in the first place.

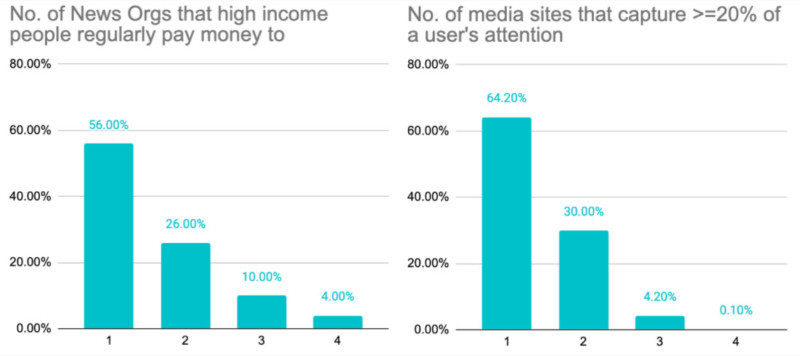

Why is that attention share important? The charts below show the RISJ data compared to Nielsen attention data. On the left is the RISJ distribution of number of subscriptions. On the right is a custom Nielsen analysis of the distribution of the number of sites that capture at least a 20 percent attention share among media sites.

Left: Digital News Report 2019, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford. Right: a private Nielsen study commissioned by Scroll labs inc.

The normal caveats about causation apply here, but the correlation between attention share and subscriptions is striking. It suggests that a successful strategy requires not just a focus on differentiated content but producing enough of it to capture attention share. It’s the same lesson that Netflix learned well: quality and differentiation are important variables, but attention share is the top priority for growing a subscriber base.

This is where the rich-get-richer dynamics of digital subscriptions prove so useful to the Times and so devastating to everyone else. The more subscribers it has, the more it can use that revenue to add more writers or build more products, which further improves its ability to capture attention share—leading to more subscribers. And the gap widens.

Imitating the strategy of the Times in a separate market makes sense. Doing so in direct competition with the Times, in a one-slot world, is slow strategic poison.

Making weaknesses strengths

What to do? A coalition of smaller players can work together to offset the singular strength of the dominant player. However, past proposals for networked subscriptions have simply thought to combine local publications, without recognizing that few Seattle Times readers care about access to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The content that makes them differentiated to their own audience makes them irrelevant to others.

The area where combining local content does make sense is sports news. If the Philadelphia Inquirer and the Chicago Tribune offered subscribers shared access to their sports content, this would be noncannibalistic and would increase the attention share associated with a subscription. The Matchup initiative, championed by Mike Orren of the Dallas Morning News and the Local Media Consortium, is a great first step.

Beyond sports, there are two approaches to a network strategy that would vastly improve the ability of other news publishers to compete with the Times: a hub-and-spoke strategy centered around the Washington Post; or a strategy modeled on cable.

A hub-and-spoke strategy

The Washington Post’s breadth of quality coverage has earned it more than two million subscribers. However, approximating the Times’ strategy over the past few years in a rich-get-richer market has led the Post to fall further behind.

While the Times is famously insular and slow to collaborate, however, the Post has leveraged a large and innovative base of tech talent to embed collaboration with other publishers into its DNA, first by enabling its Arc CMS on hundreds of sites, and now with the rapid growth of Zeus, a revenue management platform.

In a hub-and-spoke network, a digital subscription to the Post is combined with a local publisher in a series of bilateral skinny bundles. For example, the Seattle Times may struggle to compete with the Times on its own, but a subscription that provides the combined local and national coverage of the Seattle Times with the Post for the same price as the Times is far more attractive.

The Post made a half-hearted attempt at this in 2014, giving digital access away for free with subscriptions to six metro papers in a bid for audience reach. Without a clearly defined revenue arrangement, the deal felt too uncertain for publishers to effectively market, and quietly faded from view.

Distributing subscription revenue based on attention share would be more effective. A Seattle Times subscription is $16 a month. We can set aside $6 for the Seattle Times as a revenue buffer, and put the remaining $10 into a pool based on attention share. If the Seattle Times subscriber spends 50 percent of their time on the Post’s site, then the Seattle Times makes $11 that month and the Post makes $5.

The Seattle Times is trading some Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) dilution for the capacity to attract a dramatically larger subscriber base and to increase overall revenues. (They already do this through strategies like discounted subscriptions.) However, they are only doing so among the subscribers who actually get significant value from the combination. If the subscriber realizes no additional value, there is no dilution.

The Washington Post is not realizing its normal ARPU, but these are unlikely to have been subscribers it could have acquired on its own. These subscribers represent new cash flow at near zero marginal cost. The hub-and-spoke nature of the bundle protects their existing subscription base from ARPU dilution. The small number of Post subscribers with an interest in Seattle who switch to the bundled offer would still spend much of their time with the Post, making dilution minimal. In addition, this would likely be more than offset by subscriber growth.

Adopting the hub-and-spoke model would make metro publishers competitive in their own backyard. They trade some variable ARPU for a far greater subscription base and a competitive future. It also puts the Washington Post on a dramatically different path to success: no longer a mini monolith, it is the nexus of a network of successful publishers.

Common content in a one-slot paywalled world

The logic of the single slot requires us to unlearn the lessons of the open internet. With print, we had non-overlapping audiences divided by geography. There was little risk of a Minneapolis Star Tribune reader switching to the Sacramento Bee. Publisher value was built on a combination of shared wire service content providing breadth, augmented by homegrown reporting providing differentiation. With the open internet, we had overlapping audiences where it was as easy for a Californian to read the Boston Globe as the LA Times. Publishers lost the value of shared wire content and value became restricted to homegrown differentiation.

In a paywalled, one-slot internet, this thinking changes. The industry hasn’t yet embraced how much. We now have non-overlapping audiences divided by subscription. That opens the door to leveraging common subscription-only content that can be shared across multiple publishers to create enough value for a larger audience to value a single news subscription. This is then augmented by homegrown differentiated content that defines which publisher should be the entry point for that value—like cable companies.

Common content in a one-slot world is what formed the core of the cable bundle. Universally attractive premium content such as ESPN or HBO was successfully able to provide shared value among many cable providers as long as it consistently required a cable subscription to access it, and the average number of cable subscriptions that a household would have was one.

For a subscriber to the Miami Herald, the local newsroom would focus on what it does best: generate superb local content. However, under an adapted cable model, that Herald subscriber would also get access to a shared trove of subscription-only content: Business, Opinion, Analysis, Tech, Features, Science, Race, Gender, Health, Lifestyle, Productivity, Arts, Books, Style, Food, Short-form Fiction, Travel. Content that the Herald could not afford to create on its own. That this content is also available to subscribers of the San Francisco Chronicle or the Chicago Tribune does not change the value of the subscription to the Herald subscriber, as they cannot freely access that content on other sites.

There’s currently a glut of independent talent that could be creating subscription-only content in areas that would dramatically augment the value of a local news subscription. The marketplace and mechanisms for revenue distribution in such a system have yet to be built, but the broad architecture is clear.

A future for news organizations beyond the New York Times does exist. We can’t know for certain whether the options outlined above are the right way to go—but we do know that simply cargo-culting the Times will only escort us into twilight.

Disclosure: The New York Times is a small minority investor in the author’s company. It had no involvement in the drafting of this article and would probably rather he hadn’t written it in the first place.

FROM THE LATEST ISSUE: The Defunding Debate

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.