In April of 2018, Daniel Ortega, the president of Nicaragua, announced reforms to the country’s social security benefits. Protests erupted, following years of discontent with the increasingly repressive regime. The Ortega government responded with brutal crackdowns on protesters, political opponents, and the independent press that still have not abated.

As protests gained momentum that April, Ángel Gahona––an investigative journalist who ran El Meridiano, a local television news outlet––was shot and killed as he was livestreaming an anti-Ortega demonstration. Gahona’s family, and other reporters who were on the scene with him, believe the national police killed him, they told The Guardian, even as the government maintains otherwise.

Ángel Gahona’s family members during a vigil for murdered journalists. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

Months later, the government placed a blockade on materials needed to print newspapers, critically impairing two major independent news outlets, La Prensa and El Nuevo Diario. In December of 2018, national police ransacked the newsrooms of Confidencial (a news site), Esta Semana, and Esta Noche (TV news programs), which are all run by one of the country’s most prominent journalists, Carlos Fernando Chamorro. Officers seized computers and other materials from the newsrooms. “They are physically closing down our offices by taking them militarily,” Chamorro told The Guardian. Police also raided Niu, an independent magazine.

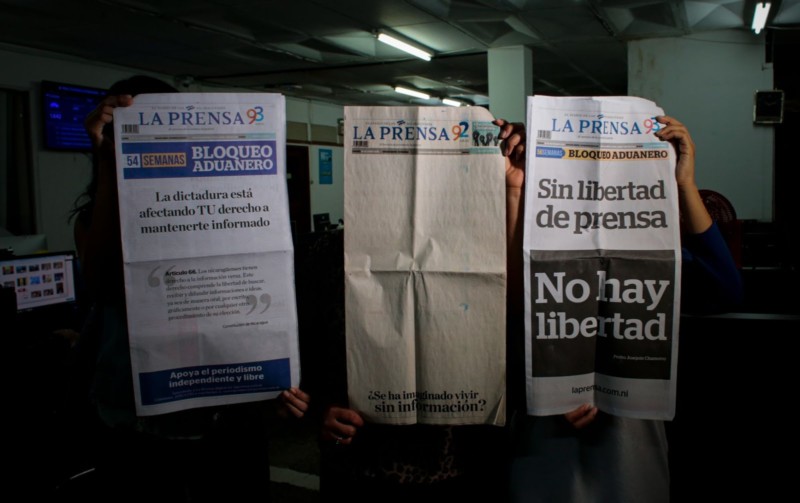

La Prensa workers show a blank front page as well as two other pointed covers as a sign of protest. They read: “The dictatorship is affecting YOUR right to stay informed”; “Have you ever imagined living without information?”; “Without freedom of the press, there is no freedom.” Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

Days later, police raided and confiscated equipment from 100% Noticias, an independent news network. They arrested Miguel Mora, the founder and owner of the station, and Lucía Pineda, the news director. At first, Mora and Pineda were held in a prison that Human Rights Watch called a torture site; they were later moved to maximum-security prisons. “We were locked in cells of total isolation, like small graves. There were very narrow windows. I did not talk to anyone. We were basically buried alive,” Mora told the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Carlos Fernando Chamorro, the director of Confidencial, peers into his ransacked office in Managua. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

By the middle of 2019, more than ninety Nicaraguan journalists, Chamorro and Pineda among them, had gone into exile in Costa Rica.

Carlos Fernando Chamorro and his wife in the Managua airport, returning from exile in Costa Rica. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

Attacks on press freedom have remained at historically high levels. From April 2018 to March 2019, press freedom violations increased more than one thousand percent from the past year, according to the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation. Sixty-one cases of violence against journalists were documented between December 2019 and February 2020, along with three hundred thirty-eight cases of press freedom violations between January and November 2020.

Arlen Cerda, an editor for Confidencial, is removed from the National Police headquarters, Plaza El Sol. Cerda and Carlos Fernando Chamorro, her boss, were trying to investigate why the police had raided their office. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

In October 2020, the National Assembly approved a group of laws that criminalize and promote censorship over journalism. A cybercrime law, for example, renders the spread of “fake news” punishable with up to five years in prison. The foreign-agents law––which requires Nicaraguan groups, including news outlets, to register as “foreign agents” if they receive any funding from outside the country, even indirectly––led to the closure of the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation, pen

International’s Nicaragua chapter and other nonprofit media organizations.

In recent months, several Nicaraguan journalists have been prosecuted. National police have raided their homes. Ortega loyalists have assaulted journalists. In late May, police raided Esta Semana and Confidencial again; they detained a cameraman, Leonel Gutiérrez, the only person in the newsroom at the time. That same day, police detained and attacked journalist Luis Sequeira, a correspondent for the Agence France-Presse, who was quickly released.

Riot police line up across from the 100% Noticias building. They blocked access to the newsroom during the arrests of Miguel Mora and Lucía Pineda. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

In May, the Ministry of the Interior summoned Cristiana Chamorro––a prominent journalist, former director of the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation, and daughter of the president who beat Ortega in 1990––and two other former officials to inquire about alleged inconsistencies in the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation financial statements. Under threat of money-laundering charges, the foundation, which monitored press freedom in the country, shut down in February.

Cristiana Chamorro, former director of the Violeta Barrios de Chamorro Foundation, prepares to address journalists shortly after meeting with government officials in Managua in May. Photo by Oswaldo Rivas

Nearly two dozen journalists, as a result of the Ortega investigation, have been called on to testify under oath. This week, the government added thirteen news organizations to its investigation, which leaders around the world have denounced as a farce. Cristiana Chamorro, a popular figure who is also planning to run for president, is currently under house arrest. On Sunday, police detained Mora––another presidential candidate; the fifth to be arrested––and ransacked his home.

Oswaldo Rivas is an award-winning Nicaraguan photographer. He began in the world of photography in 1988 at the Nueva Nicaragua International News Agency (ANN) as a war correspondent covering the country's civil war. In 1993 he was head of photography for La Tribuna. From 1997 to 2020, he was part of the team of photojournalists for Reuters. He currently works as a freelancer. His work has appeared in the New York Times in the US, El País in Spain, Gente in Italy, La Reforma in Mexico, and many more outlets.