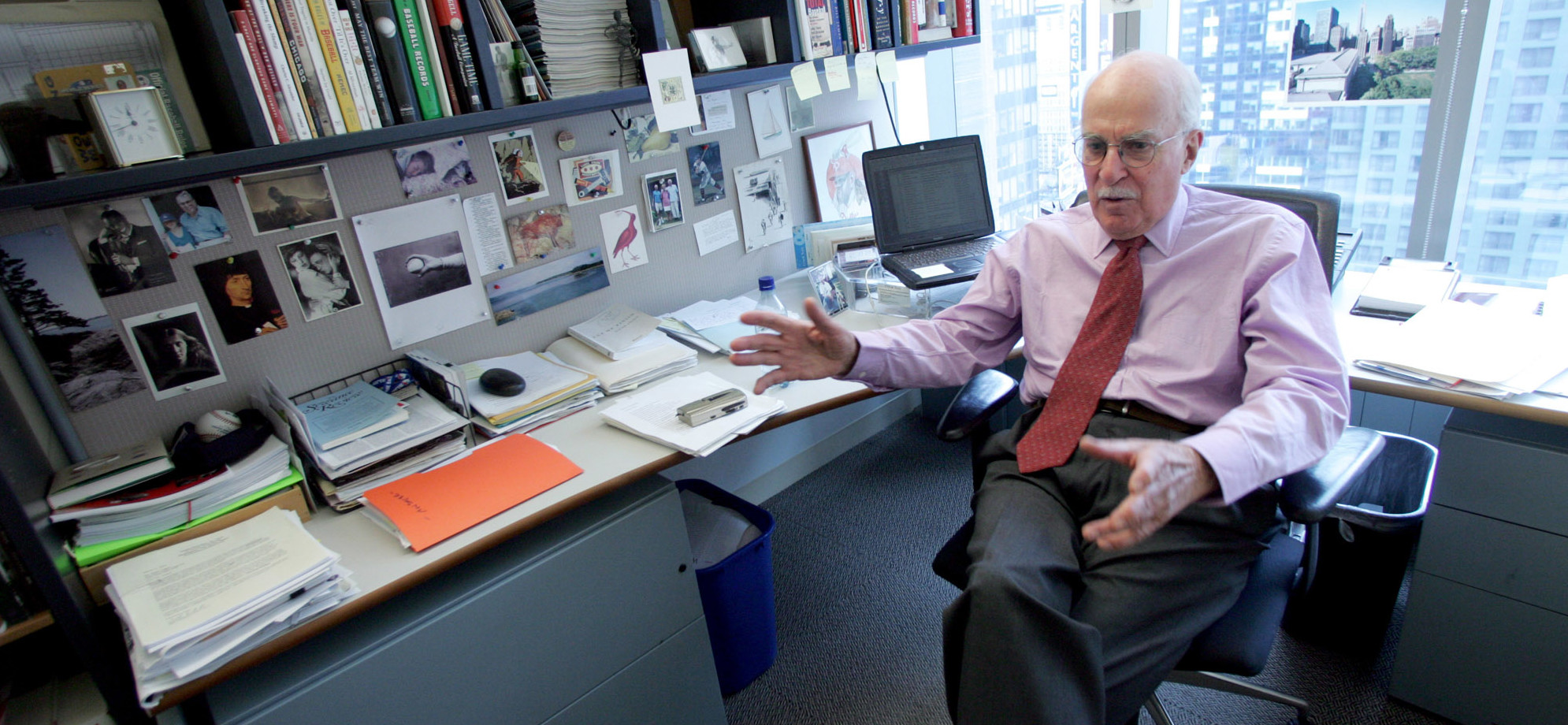

Tomorrow is Roger Angell’s hundredth birthday. I met Roger at The New Yorker, where he has contributed since 1944. I was assigned to be his assistant; we’ve since become dear friends. Reading his pieces, many of them about baseball, a few things are obvious: Roger is a terrific noticer. He has an extraordinary talent for finding just the right word. He douses the page with sincerity; he is willing to embrace all the tragedy and comedy of human experience. Roger has had the great fortune of being an editor and writer for a magazine that let him contribute pieces when he wanted to, not on demand. (“I’ve had a life sheltered by privilege and engrossing work,” he wrote in 2004.) Free from the burdens and pretenses of a daily reporter, he has been able to engage people in meaningful conversation. He has the time to devote to his subjects, and he takes it, yet his pieces feel precise and effervescent, never labored. A Roger story has a sense of being organic, solid, destined—like an outcropping of schist in Central Park where people come to sit. The rock wasn’t always there, but it feels like it was meant to be.

Journalism owes Roger so much—for the fabulousness of his prose, for the way he’s inspired generations of sportswriters, for his model of decency. The best way to celebrate the first hundred years of Roger’s life may be to read his stuff. I asked him to make a few selections:

From 1973, there’s “Three for the Tigers,” about, of course, three Tigers fans in Detroit. From 1976, “Scout,” on Ray Scarborough: “In this scene, a man sits alone on a splintery plank bleacher seat, with a foot cocked up on the row in front of him and his chin resting on one hand as he gazes intently at some young ballplayers in action on a bumpy, weed-strewn country ballfield,” Roger writes. “He sits motionless in the hot sunshine, with a shapeless canvas hat cocked over his eyes. At last, responding to something on the field not perceptible to the rest of us, he takes out a little notebook and writes a few words in it, and then replaces it in his windbreaker pocket.” That last line might also belong in a self-study.

In 1980, Roger profiled Bob Gibson in “Distance,” which has one of his favorite question-and-answers of any story: “Someone asked him if he had been surprised by what he had just done on the field, and Gibson said, ‘I’m never surprised by anything I do.’ ” Roger’s favorite baseball piece may be “In the Country,” from 1981, about a semipro pitcher named Ron Goble and his partner, Linda Kittell, a writer. It begins, “Baseball is a family for those who care about it.” Also from 1981 is “The Web of the Game,” in which Roger is in the stands with Joe Wood, “an old gent with a cane,” who was once the baseball coach at Yale and, before that, known as Smoky Joe Wood; in the piece, Wood is ninety-one. In Game Time, you’ll find “The Purist,” on Ted Williams, and “Blue Collar,” about the Milwaukee Brewers and St. Louis Cardinals in 1982. In the latter piece, Roger writes, “This seven-game Series, which was captured at very long last by the Cardinals, lacked for nothing but restraint and consistency, and its motto might have been ‘Both Things Are True’ ”—a phrase I’ve heard him say often, outside the context of baseball, and there’s lots of wisdom to it.

We both love “In the Fire,” from 1984, about catchers. “Armored, he sinks into his squat, punches his mitt, and becomes wary, balanced and ominous; his bare right hand rests casually on his thigh while he regards, through the portcullis, the field and deployed fielders, the batter, the base runner, his pitcher, and the state of the world, which he now, for a waiting instant, holds in sway,” Roger writes. “The hand dips between his thighs, semaphoring a plan, and all of us—players and umpires and we in the stands—lean imperceptibly closer, zoom-lensing to a focus, as the pitcher begins his motion and the catcher half rises and puts up his thick little target, tensing himself to deal with whatever comes next.”

For some non-baseball reading, open up Let Me Finish and turn your hymnal to page 272 for “Jake,” Roger’s piece about a writer named John F. Murray. You’ll also want to read “Andy,” about Roger’s stepfather, E.B. White. “White’s gift to writers is clarity, which he demonstrates so easily in setting down the daily details of his farm chores: the need to pack the sides of his woodshed with sprucebrush against winter; counterweighting the cold-frame windows, for easier operation; the way the wind is ruffling the surface of the hens’ water fountain,” Roger writes. He describes White as “the first writer I observed at work,” revising endlessly, sometimes morosely. “Writing almost killed you, and the hard part was making it look easy.”

Finally, there’s the one you already knew he’d pick, the one you may have already revisited recently: “This Old Man.” (The Andy this time is his dog, a smooth fox terrier.) Describing life in his nineties, Roger imagines what people are thinking when they see him: “Holy shit—he’s still vertical!” He then proceeds to tell us more of what’s going on inside. “Getting old is the second-biggest surprise of my life,” he writes, “but the first, by a mile, is our unceasing need for deep attachment and intimate love.”

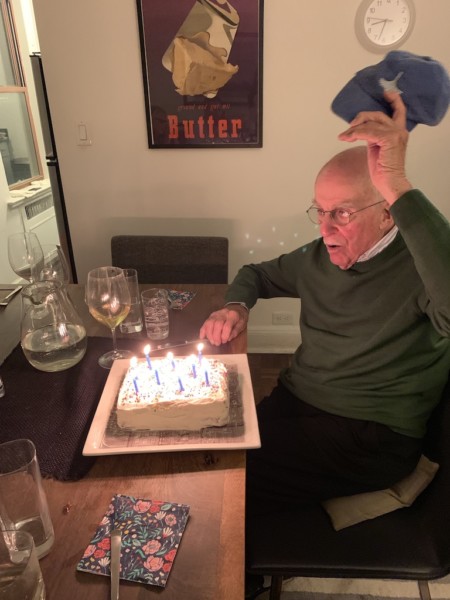

Angell, in a photo taken last year, celebrates his 99th birthday.