Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the Serial podcast craze has been the amount of audience interaction with the story, a novel phenomenon for today’s journalists, though not historically. As Sarah Koenig and her team reported on the case, they didn’t know how it would end, leaving a vacuum for listeners to fill.

A Reddit page devoted to the podcast has nearly 45,000 subscribers, and there are countless tweets and blog posts, each with theories about whether or not Adnan Syed is indeed guilty of killing his ex-girlfriend in 1999. The vast majority of this amateur sleuthing was maladroit at best, but at least one listener advanced the case when even Koenig could not.

“I was listening to the podcasts, and started blogging about it, because I was getting frustrated with the way the narrative was trying to explain the cellphone evidence,” said Susan Simpson, a lawyer in Washington, DC. “I don’t think they did a bad job, but in terms of the medium, it’s hard to adequately explain what was going on.”

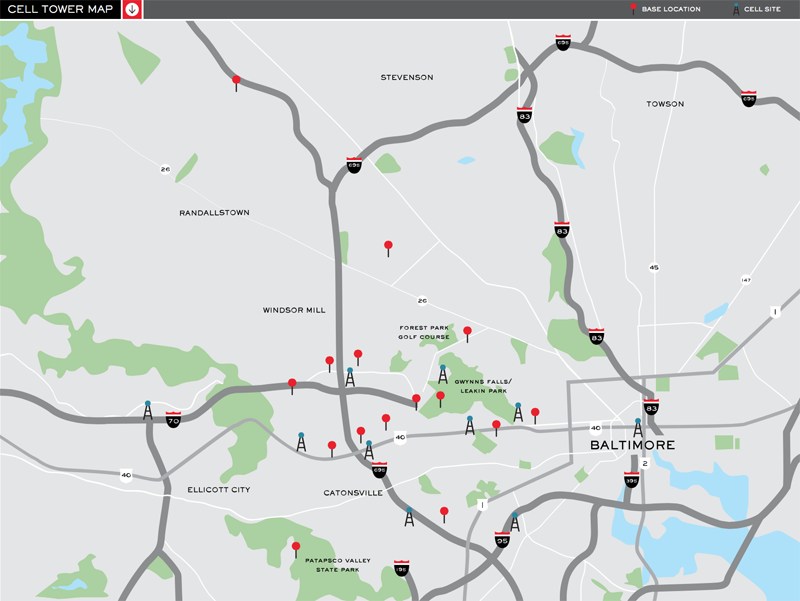

The cellphone evidence was the prosecution’s claim that Syed’s phone location data matched the timeline put forth by Jay Wild, the key witness in the case who testified that he was with Syed the day of Hae Min Lee’s murder. Koenig had an impossible task presenting this evidence via audio. There were dozens of calls that pinged dozens of cell towers, with names like tower “L648C” or “L689B.”

For simplification, Simpson mapped each call and made charts to see which calls matched Wild’s testimony and which didn’t. She found that many of the calls submitted as evidence were in areas of overlapping tower coverage, while others were to towers miles away from where they should be in Wild’s narrative of events. Perhaps most damning was a statement submitted by AT&T to the prosecution that only outgoing calls are considered reliable for determining a phone’s location status; incoming calls were not. “After I did that, I started getting more into the legal disputes,” she said. “And once I started doing that, the case started falling apart.” Rabia Chaudry, one of Syed’s closest friends and biggest public advocate for his innocence, expects Simpson’s work to be used in Syed’s upcoming appeal this summer.

Simpson’s investigation may harness the connectedness of the digital age, but it’s not a new way for audiences to react to compelling journalism; in a way, this unusual-seeming rush of audience participation is actually a throwback. In the late 19th century, when William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer competed for mass urban readership, true crime stories were all the rage, and papers would encourage audience interaction. One example of this, according to Columbia Journalism School PhD director Andie Tucher, was all the amateur sleuths investigating the murder of William Guldensuppe.

In 1897 bits and pieces of a body were turning up across New York City wrapped in oilcloth. First a torso was found by boys swimming in the East River. Then a pair of legs in the Brooklyn Navy yard. Soon body parts were being found in Harlem and the Bronx. According to Tucher, Newspapers appealed to their readers to solve the case: “They published drawings, saying things like ‘Here’s the torso,’ and ‘Here’s some tattoos’ and ‘Here’s the hand,’ and ‘Here you see the finger is broken,’ asking everyone, ‘Do you know this man?’”

Readers went to shops all across the city looking for a salesman who sold oilcloth with the same pattern the body parts were wrapped in. Some of Guldensuppe’s colleagues recognized his broken finger and tattoo and reported he was the victim. Thanks to the diligence of its readers and reporters, on June 30, 1897, Hearst’s New York Evening Journal triumphantly screamed the headline: “MURDER MYSTERY SOLVED BY THE JOURNAL!”

Other instances of audience interaction were abundant: Readers played with diagrams charting Nellie Bly’s attempt to travel around the world in 80 days, and her publisher sold authentic Nellie Bly caps to her fans. Today, amateur Serial detectives can buy an official red leather notebook embossed with the series’ logo on the cover, and use it to push the narrative forward.

By the early 20th century, this heavy reliance on audience interaction went out of style. It wasn’t seen as objective, and newspapers relied more on expert journalists and expert readers. In that vein, Koenig has said that she feels responsible for the story and didn’t want to rely on an online community to attempt to solve the case because she felt responsible to report the story accurately. But in the age of Twitter, interactivity may be taking a page out of the 19th-century playbook.

“Anything [Simpson has] uncovered or analyzed—because sometimes it’s a discovery, and sometimes it’s an analysis of things—gets passed on to [Syed’s] attorney immediately,” Chaudry said in an interview. “Susan’s been really amazing at parsing the cellphone evidence and bringing it to experts to show how they’ve been completely misused.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.