Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In Suffragette, a movie due out in October, Meryl Streep portrays Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the early 20th-century British movement that helped get women the vote. In a discussion of the movie on a women’s group forum, one member objected to the term “suffragette”: The “-ette” suffix is a diminutive, the member argued, meaning it conveys the idea of cuteness, smallness, or less import than the root word. Instead, the member said, these women should be called “suffragists.”

But it turns out there are shades of “suffrage.”

Despite its resemblance to “suffering” and the common misspelling “suffrance,” “suffrage” does not involve grief, misery, or woe (unless you were at the other end of some of the “suffragettes’ ” arson attacks).

“Suffrage” originally meant prayers, especially prayers on behalf of someone else, often the dead. The word entered English about 1380, according to The Oxford English Dictionary, and about 200 years later came to mean “a vote given by a member of a body, state, or society, in assent to a proposition or in favour of the election of a person.” Not just a vote; a vote in favor of something. It wasn’t until 1665 or so, the OED says, that “suffrage” came to mean the right to exercise a vote.

“Suffragist” entered in 1822 in England, the OED says, to mean “an advocate of the extension of the political franchise.” In the United States, though women had been seeking the vote since before the Civil War, “suffrage” and “suffragist” was applied mainly to the movement to give black men the vote, which happened officially if not actually in 1870. After about 1885, “suffrage” was applied almost exclusively to the movement of women seeking the vote, the OED says. (American women finally got the vote nationally in 1920, eight years before women in Britain were enfranchised.)

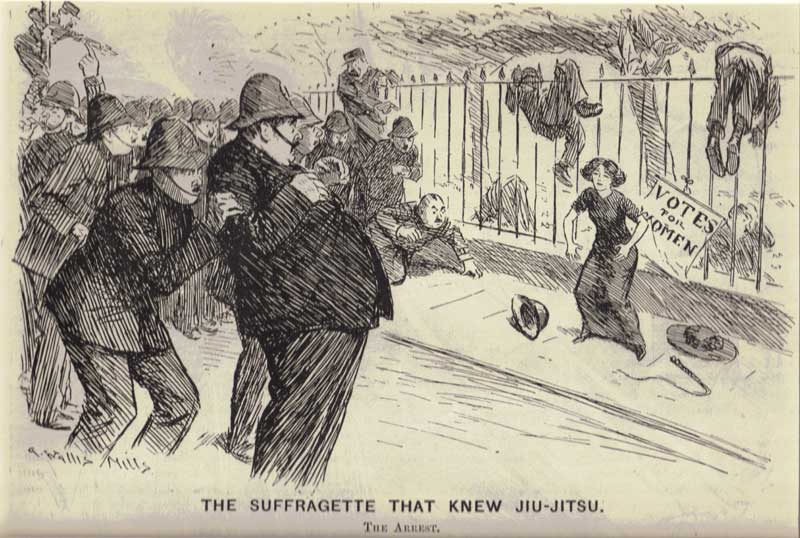

The Suffragette that Knew Jiu-Jitsu. The Arrest. By Arthur Wallis Mills, originally published in 1910 in Punch and The Wanganui Chronicle.

And then, in 1906, the Daily Mail in London coined the term “suffragette.” Not just women seeking the vote, these were the “violent or ‘militant’ type” of women seeking the vote: They chained themselves to railings, set buildings on fire at night and went on hunger strikes, among other tactics. While the Daily Mail wanted to differentiate the militants from the “suffragists” who had been more peaceably seeking the vote in England since the 1860s, it also wrote derogatorily about the “suffragettes,” so perhaps the “-ette” suffix was a deliberate demeaning of the movement. But the militant Women’s Social and Political Union, headed by Emmeline Pankhurst, quickly adopted the term for itself. So by that measure, “suffragette” is correct for the movie and the woman in this instance.

Before 1908, at least in The New York Times, women (and blacks) seeking the vote were only “suffragists.” The Times used “suffragette” for that more militant movement in England, until 1908, when it started distinguishing between “suffragist” and “suffragette” in the United States as well.

The suffragists (emphasis on the last syllable) were talking yesterday about the suffragettes (emphasis again on the last syllable). The suffragists said that the suffragettes had put back the cause of votes for women ten years by their Wall Street meeting on Thursday. At different women’s meetings yesterday the subject was brought up, either officially or in private conversation. (Italics added.)

This being the early and genteel 20th century, the article of course noted that, at one meeting, “the decorations for the tea were in suffrage yellow.” And each married women was identified by her husband’s first name, not her own.

So while women had come a long way, they still had some way to go.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.