Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Last night, at the event space of The New York Times building, a collection of Black journalists, poets, and museum curators announced their intention to tell the truth about slavery. Announcing the debut of The 1619 Project, a special issue of the Times magazine published with additional material in the newspaper, Nikole Hannah-Jones, a staff writer, told the crowd, “This project is, above all, an attempt to set the record straight. To finally, in this 400th year, tell the truth about who we are as a people and who we are as a nation.” She went on, “It is time to stop hiding from our sins and confront them. And then in confronting them, it is time to make them right.”

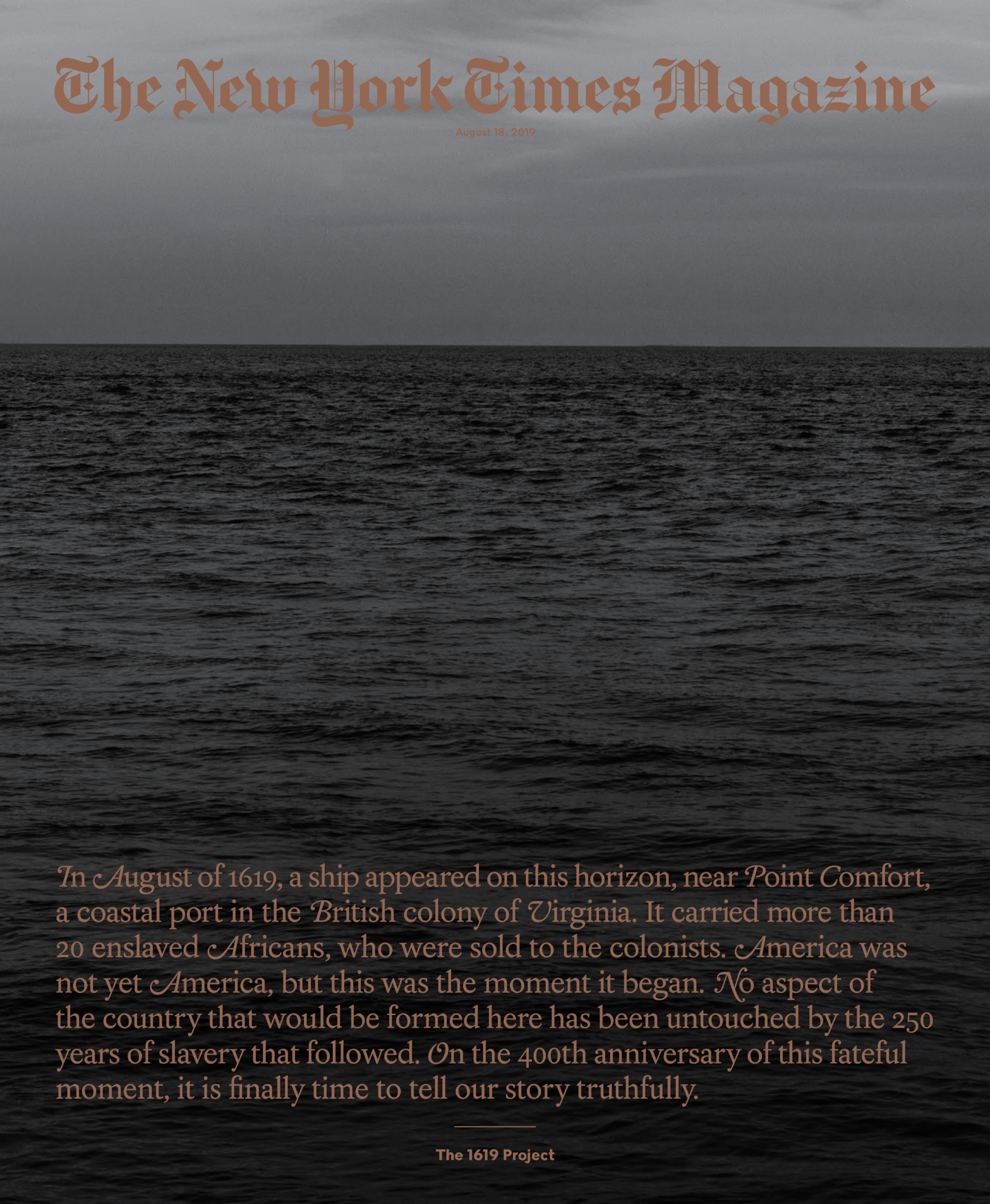

Several hundred people filed into plush red velvet chairs for a launch event; hundreds more tuned in online. The issue, Hannah-Jones explained, marks the 400th anniversary of the first arrival of enslaved Africans, aboard a Portugese slave ship to Port Comfort, in the British colony of Virginia. It is a historic moment that typically passes without acknowledgement from news outlets or the general public.

In the American psyche, slavery is regarded in the past tense; it is thought of and written about as a distant blip on the extended timeline of United States history, an unfortunate atrocity of long ago. But violent chattel slavery and the systems of apartheid that followed it defined this country before it even had a name. Slavery informed every institution, from politics to healthcare to housing infrastructure. Knowledge of its mechanisms puts in context all of today’s struggles for equity and, by extension, every attempt to document them. Yet the record does not adequately reflect that, like the founding documents of this country, our misunderstanding of slavery’s awful influence is deceit by design.

Inside the magazine, Black reporters, novelists, poets, photographers, historians, and artists reframe American history, centering the arrival of those first few dozens of enslaved Africans, whose descendants would become the first African-Americans; the brutality white colonists would spend centuries perfecting and protecting; and the persistent resistance of Black people that pushed the US to live up to its own ideals. “What if America understood, finally, in this 400th year, that we have never been the problem but the solution?” Hannah-Jones writes in the opening essay.

Contributors consider various modern quandaries—rush hour traffic, mass incarceration, an inequitable healthcare system, even American overconsumption of sugar (the highest rate in the Western world)—and trace the origins back to slavery. Literary and visual artists drew from a timeline chronicling the past 400 years of Black history in America; their work is presented chronologically throughout the magazine. Taken together, the issue is an attempt to guide readers not just toward a richer understanding of today’s racial dilemmas, but to tell them the truth. For many, it may be the first time they’ve heard it.

In addition to the magazine, a special section of the Sunday newspaper, made in partnership with the Smithsonian, will examine the genesis of what would become the transatlantic slave trade, beginning with the Roman Catholic Church’s granting of a monopoly on trade in West Africa and Spain to Portugal, in the 15th century. Full-page images display artifacts, such as iron ballast blocks that were used to counter the weight of enslaved men, women, and children as they made their way across the Middle Passage. Today, the blocks cover the streets of Charleston, South Carolina. The insert also explores how and why American schools failed to teach children this significant history and, in partnership with the Pulitzer Center, the Times has offered curricula, including lesson plans, guides, and activities to help teachers bring this material into their classrooms. The Daily, the morning news podcast of the Times, will debut a multi-episode series dedicated to The 1619 Project beginning August 20. The Sunday sports section will feature a story exploring slavery’s impact on professional sports. Jake Silverstein, the editor of the Times magazine, promised more stories and events in the coming weeks and months.

The effort began with a pitch. Hannah-Jones wanted to dedicate an issue to this underappreciated anniversary and challenge the notion that American history begins with victory in 1776. The staff quickly got on board, she told guests at the event, and the project grew. The goal, Silverstein writes in his editor’s note, is to consider what it would mean to shift our perception of America’s birth to the year 1619. Doing so, he writes, “requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.”

For generations, journalism has papered over slavery’s impact, at times openly advocating the white supremacist ideologies that enabled the founders of the United States to justify treating human beings as property fit only for forced labor. Language—the selection of words—is the spine of journalism, and just as our views of American history need recalibrating, so too does the language we use to describe it. Throughout the evening’s program, Hannah-Jones corrected the language typically used to describe slavery and Black subjucation: Africans were not just brought to North America, they were kidnapped. The Middle Passage was, Hannah-Jones writes, the “largest forced migration in human history until the second World War.” Plantations were forced labor camps. Black Americans, post-slavery, fled racial apartheid in the South; they were refugees in their own country.

The media has enabled and contributed to the mischaracterization of American slavery. Stories refer to it, tonally, in radically different terms than atrocities like the Holocaust or South African apartheid—both human rights violations that the US opposed on international stages, with the help of Black soldiers, while Black Americans were denied constitutional rights at home. Perhaps most pernicious is the insistence on slavery as a historical fact, rather than a present day influence.

“Like most Americans, slavery was largely taught to me as something that was marginal to the American story,” Hannah-Jones said in the program’s opening remarks. “Slavery had to be mentioned in our history books because we had to talk about the Civil War, but outside of that, it was just a brief discussion that relegated slavery largely to the backwards South, and assured us as a nation that slavery had little to do with how our country developed.”

For the media to tell the truth about the US, it must commit to both a reeducation of its readers and of its workers. Efforts like The 1619 Project look backwards to inform a path forward. But to really reach the truth, journalists must make a sincere effort to interrogate our daily performance such that, some day, we won’t need to correct the record, because the record will have been accurate the first time.

“How are we replicating these dehumanizing narratives every single day?” Eve L. Ewing, a sociologist and writer asked the crowd at the launch event. “How are we, in fact, at risk of undermining this kind of great work if it sits in parallel to rhetoric that continues to demonize and dehumnanize Black people, Black trans people, Black undocumented people, Black disabled people, Black queer people, Black people with HIV, Black poor people, and so on?” Ewing, who contributed a poem to the magazine about Phillis Wheatley, the first African-American woman to publish a book of poetry, went on: “That’s the kind of questioning that we have to take into all of these institutions. It’s not just learning lots of facts, but learning modes of questioning that we need to be constantly interrogating in a time when we’re facing the rise of authoritarianism, which rests upon regular people doing nothing and asking nothing.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.