Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

When longtime labor reporter Steven Greenhouse took a buyout from The New York Times in December, the funeral dirges began. The labor beat has “waned with the power of organized labor itself,” The Washington Post conceded, while a Huffington Post headline proclaimed that it “keeps shrinking.” Daily Kos described the move as “really sad news,” and Salon lamented the “end of an era.” A Politico Magazine headline summed up much of the collective consternation: “Does the media care about labor anymore?”

It’s a fair question. The Times was initially unsure whether it would hire a replacement for Greenhouse, temporarily leaving just one major US newspaper, The Wall Street Journal, with a full-time reporter covering issues ranging from federal labor policy to worker protests to employee rights. Greenhouse responded to the elegies by making rounds on the media interview circuit. But his prognosis was far different.

“I was flattered at the outpouring of support when I announced I was taking the buyout from the Times, and a lot of people said that it was the death of labor coverage,” Greenhouse told me. “That’s exaggerated, hyperbolic, and somewhat wrongheaded.”

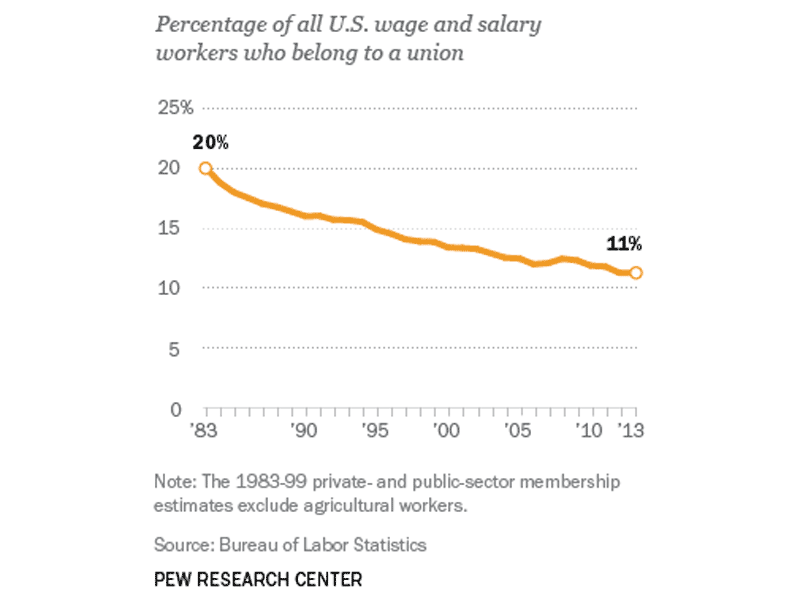

It’s also too simple. The ranks of the labor beat have indeed hollowed out alongside the atrophy of organized labor, continuing as news organizations have more recently hemorrhaged cash. But the beat historically focused on unions, a focus unsuited for an economy in which just 11 percent of American workers belong to them. “The old fashioned idea that you’re covering just organized labor went away a long time ago,” said Dean E. Murphy, business editor of The New York Times.

The proportion of US workers who belong to a union has declined from its mid-1950s peak around 35 percent. (Source: Pew Research Center)

Labor is nearly universal, of course. And as the American economy has become increasingly complex, so too have workplaces and media coverage of them. The Great Recession threw many of these changes into sharp relief, and workers’ issues have grown in prominence from fast food restaurants in Seattle to the halls of power in Washington. Many news organizations, meanwhile, have since channeled more resources toward such topics, if not dedicating full-time reporters to them. The new normal poses important questions about the future of this reporting, including continuity of coverage and policy or geographic expertise. But it’s clear that media outlets are waking up to the plight of the American worker. The labor beat is dead; long live the labor beat.

“There is no firm line that separates labor from anything else,” said Josh Eidelson, a former union organizer who now covers labor for Bloomberg Businessweek. “I don’t think it’s possible or productive to distinguish between what’s a labor story or education story or LGBT story…Labor, broadly speaking, is a huge part of American life, so publications should put a lot of resources toward that. And that’s more important than making sure they specifically dedicate someone to the beat.”

A number of nationally focused news organizations have indeed hired journalists to focus on the American workplace — a wide-ranging topic, to be sure. The Huffington Post assigned a reporter to it starting in 2011, and Politico launched a four-person labor team in October. The New York Times’ replacement for Greenhouse, ex-New Republic staffer Noam Scheiber, started in late February. BuzzFeed is also in the process of hiring a labor reporter, business editor Tom Gara said.

“There are a lot fewer people covering the topic than there used to be, and because of that, hiring a reporter could potentially have a higher return for us,” he added, noting that much of his site’s audience is in the beginning or middle of their working careers. “We thought having a person on that beat will give us an opportunity to incrementally advance these [workplace] stories.”

Far more media outlets have added labor coverage from elsewhere in the newsroom. The Washington Post’s Lydia DePillis has become a leading voice in the online conversation, even though she also covers housing policy. The Boston Globe created a “workplace and income inequality” beat last spring, and the Los Angeles Times has produced compelling work on issues such as the West Coast ports labor dispute in lieu of a dedicated beat writer.

Data journalism and interactive graphics have made everything from numbers-driven labor market analysis to human-driven workers’ comp exposés more digestible and informative. The topic also plays well to feature and investigative work. The Center for Public Integrity’s Chris Hamby won a Pulitzer in 2014 for his series on how West Virginian coal miners suffering from black lung were often refused benefits. And Slate’s Working podcast profiles various American workers, from porn stars to hospice nurses.

“Writing about labor is writing about people and what they do with their time to earn money; it’s about writing about their struggles and their ability or inability to put food on the table; it’s writing about their relationships with their colleagues and with their employers and why those relationships matter,” added Alejandra Cancino, who splits time covering labor and manufacturing for the Chicago Tribune.

Of course, the media’s newfound attention on the workplace is partly a reaction to its previous inattention. Television coverage of labor issues has always been relatively scant or shallow. And even when newspapers were stocked with labor writers, the reporting disproportionately focused on work stoppages and their effects on consumers. When such vivid displays of tension began to decline alongside the receding political power of organized labor — to say nothing of shrinking newsrooms — the beat was treated as expendable.

But the Great Recession has since shocked the system. The economic malaise that had long plagued the working class metastasized into the middle class. Though American economic growth has outpaced that of many other large nations since then, nearly two-thirds of households earn less than they did in 2002, according to a Brookings Institution report. Even some well-off Americans, who tend to consume news more heavily than their low-income neighbors, are nursing wounds.

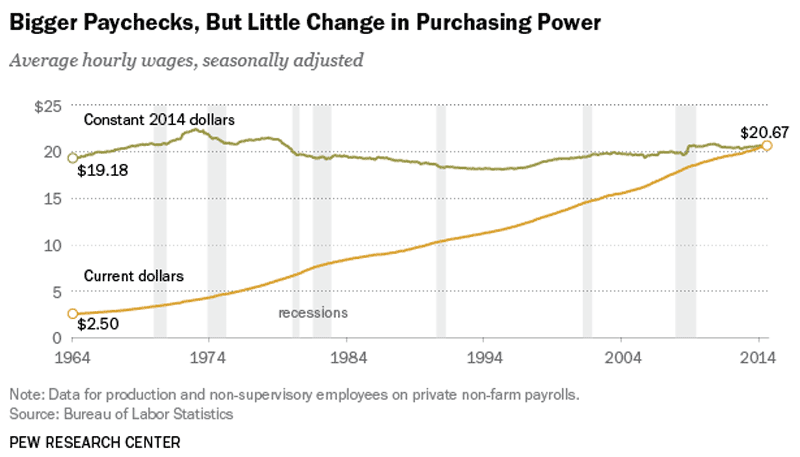

Median wages have remained stagnant as the country’s highest earners have seen bigger paychecks. (Source: Pew Research Center)

The question the media has yet to fully answer is not what is happening to American workers — they’re being squeezed, as Greenhouse wrote in a 2008 book — but rather how and why that’s happening. And that will be exceedingly difficult to do, given the paucity of daily reporting in the lead-up to the recession. Greenhouse and his contemporaries’ institutional memory can only be stretched so far in explaining how trends took shape in real time. The new era of workplace reporters, meanwhile, may be stretched too thin in covering today’s news to consistently return to the past. “I spend a lot of my day saying, ‘Sorry, I can’t cover your story,’” said Huffington Post labor reporter Dave Jamieson. “[The beat] is so wide open, and you can only get to so much of it.”

It’s telling that perhaps the most talked-about work of economics since the downturn is Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which analyzes the growth of wealth and income inequality. The debate over how to address those issues has grabbed bipartisan attention in Washington and is sure to be a central theme in the 2016 presidential campaign.

That this question has come to the fore with organized labor at an increasingly vulnerable state has also fueled media attention. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s 2011 push to curb collective bargaining rights for public employees drew as many as 100,000 protesters outside of the state capitol. Public pensions across the country are under threat as unfunded liabilities tower ever higher above state and municipal budgets. The passage of right-to-work laws in Michigan, Indiana, and Wisconsin struck decisive blows to unions in the cradle of organized labor.

“The prognosis of the US labor movement is dismal — that’s the reality,” said Timothy Noah, labor policy editor at Politico. “On the other hand, that makes this an interesting moment. If there is to be a labor moment — at least within the private sector — it will be built from the ground up. [Workers] will have to start from scratch.”

And it appears they have. The “Fight for 15” campaign has not only galvanized low-income workers across the country, but also proven adept at drawing national media coverage. The push has hinted at what a new labor movement might look like in today’s economy. What’s more, 21 states hiked their respective minimum wages in January, and Walmart, the nation’s largest employer, announced in February that it would give 500,000 of its lowest-paid workers a raise.

Resulting stories comprised more classical labor reporting. They, too, breathed additional life into today’s broadened genre, which in recent years has taken up issues such as the disjointed schedules of retail employees, how Obamacare affects workers’ health insurance plans, and the rise of contract work and franchising among corporations, creating what former academic and now-Labor Department official David Weil has termed “fissured workplaces.”

Of course, the new approach to workplace coverage also has its fair share of downsides. New hires have been concentrated at a few major outlets in New York or Washington, primarily analyzing national trends for national audiences. That won’t compensate for regional expertise lost in metro or local newspaper cutbacks. Coverage by Katie Johnston, The Boston Globe’s workplace and income inequality reporter, skews mostly toward low-income workers. But she also covers issues such as the gender pay gap, which reaches the highest rungs of white-collar employment.

“Like everywhere else, the workers with the lowest wages have seen them stagnating,” Johnston said of New England. But, she added, “[t]he economy here did not take quite the hit here as it did across the country.”

Thinning local coverage also holds the potential for national media to miss new labor models sprouting. In Chattanooga, TN, for example, Volkswagen workers’ push for a more collaborative relationship with their employer represents “a huge attempt to break away from the traditional, winner take-all-model of American labor relations,” said Bill McMorris, labor reporter for the Washington Free Beacon. “There has to be a return to local, specific coverage, because that’s what’s going to shape what eventually gets to the national stage,” he said.

Then there’s the issue of folding labor coverage into various other beats, the stopgap measure adopted by many news organizations. Political reporters may very well be able to write about right-to-work legislation, and financial reporters surely grasp pensions. But there’s value added by reporting such stories holistically. “If you have a financial guy who’s only interested in the performance of a public pension investment fund,” McMorris said, “you’re going to lose the political angle of the donations made by a public sector union to pass the law setting the rates.”

The implication is that reporters whose beats are tangential to labor might gravitate toward stories on the margins, perhaps missing core issues such as long-term economic trends and how government regulators react to them. More importantly, dedicating a journalist to the beat connotes buy-in. The Center for Public Integrity is expanding its environment and labor team to also cover issues of economic justice, such as wage theft, managing editor Jim Morris said. “It’s good for continuity and it sends a message that you’re in this for the long haul,” he added.

That’s important, as dedicated labor reporters are better positioned to cover the myriad incremental changes that add up to generational shifts. That’s what was missing leading up to the recession, and that’s much of the reason why news organizations are now playing catchup.

“There’s so much in a crisis in terms of workers today,” said Christopher R. Martin, a University of Northern Iowa professor who researches how the media covers labor and class. “But I fear that if we don’t have a labor beat, what happens when some of these issues are resolved 10 years from now? We might very well stop talking about them. And then 20 years from now, we might be asking, ‘How did we get here?’ all over again.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.