KIEV—For Ukrainian journalists, “jeans” is not just a pair of denim pants, but also a media piece published for a payment without any mention of the latter. It’s simple: you pay, they publish–this is jeans. Why “jeans”? No one really knows. But it would be fair to say that in Ukraine, secretly paid-for stories come in as many styles and are almost as ubiquitous.

“Jeans” is not a recent phenomenon here, but has been part of local media life since the early 1990s. Indeed, jeans are a natural extension of Soviet media practices that included direct government interference in the editorial policy of broadcasters and publishers, all of which were state-owned. Jeans have become especially common in Ukraine since 2004, after the Orange Revolution had perturbed the post-communist course of things, ushering in a new era of political and business conflicts. These conflicts spilled over to the pages of general-audience media and filled them with materials intended to advance policy agendas and business interests of different sides. The financial crisis of 2007-2009, which was especially hard on Ukraine, gave even more space to jeans by shrinking the advertising market, cutting off a key support of legitimate revenue.

I started preparing this story before massive protests erupted in Ukraine in response to government’s refusal to sign the Association Agreement with the European Union. The scale of the protests, and the political changes they could bring, may turn out to be the needed catalyst for major shifts in the structure and practices of Ukrainian media market, including the pervasiveness of jeans.

Prevalent as the practice is, many people aren’t fully aware that jeans exist at all—and this is a problem. This cloak of secrecy and semi-acknowledged status reduces room for informed discussion—and, ultimately, decisions—among the interested stakeholders, readers first and foremost.

In any case, leaving judgments aside, the most productive way to really understand how jeans work and why they survive in Ukraine is to trace their place in the Ukrainian media’s business model, to look at the size and pricing of the jeans market, where the demand comes from, why the supply exists. In other words, to figure out who pays the proverbial piper and why the piper lets someone behind the scenes call the tune.

Officially, jeans don’t exist—you can’t call the editorial office of a media entity and order a story for a mutually agreed-upon fee. If you try, you will hear, “We do not publish anything for money, except the conventional advertisements.”

But the reality is different. Indeed, the Institute of Mass Information, a Kiev-based NGO devoted to promoting quality journalism and educating media consumers, regularly monitors Ukrainian media to measure the incidences of jeans. The institute tracks six national newspapers and magazines, and four online publications. According to their results (all links are in Ukrainian), jeans stories in Ukrainian print publications made up an estimated six percent of all copy during 2013, while in online publications the rate is substantially higher, in August reaching a peak of 18 percent. Approximately seventy percent of jeans, according to IMI, is political, that is aimed at promoting some political party or agenda, while the rest is business-related, that is aimed at pushing some product or improving the public image of certain businessmen. Ukrainian Educational Center for Reforms, another NGO, which monitors smaller and regional-level publications, reports jeans rates of 16.3 percent in print outlets in September and 16.9 percent in online ones.

The NGOs’ methodology is straightforward: a panel of media experts read the scrutinized publications in full and identify jeans materials if a story: represents the interest of just one side; blatantly promotes certain products or services; or covers politicians at ribbon cuttings and other trivial events. If a story appears in identical form in different publications, it means it has probably been paid for. Jeans also tend to feature comments from people who are not competent to express an expert opinion on the issue being covered.

“Things will not get better after signing Association Agreement with the EU–Symonenko,” is a story ran by news website Obozrevatel.com that is an illustrative example of jeans, and has been categorized as such by the IMI experts. This piece reports the Communist Party leader Petro Symonenko’s statement on the dangers of closer integration between Ukraine and European Union for the country’s economy: a view that has always been one of the cornerstones of communists’ political platform, has been reiterated many times over the past several months of active Agreement-related negotiations, and is characterized by cataclysmic exaggerations often superseding any economic arguments. Tellingly, it is based solely on the party’s press-release. (Neither the website nor Symonenko responded to the IMI’s report or a request for comment from me.)

By general consensus in Ukrainian media circles, the amount of jeans in national print media and on TV is generally lower than online, where paid-for news may top out at about a third of the content. And in regional publications it may sometimes even outnumber the untainted material. Obviously, relative frequencies of jeans depend on the editorial policy (for some media outlets, publishing jeans seems like a conscious strategy rather than an occasional guilty pleasure) and on the season (periods of election campaigns are especially abundant).

Surprisingly, perhaps, the going rate for jeans materials at a publication that accepts them is usually not much different from what it charges for an ad of the same space. There is a wrinkle, though: since cash is the only way to pay for the jeans, it generates unreported and untaxed revenues for the publisher, which means extra profit. On the other hand, such expenses can not be used for reducing the tax base for jeans buyer, so that’s an extra cost. As a result, effective price of jeans ends up being slightly higher than that of legitimate advertisement.

Even by black market standards, pricing schemes on the jeans market are rather opaque. But ballpark figures from knowledgeable media sources that were interviewed for this story but who prefer to remain anonymous, are as follows: a lower-traffic website will publish jeans “news” for approximately the equivalent of $40; national publications will ask $200-$300. The most popular print publications charge more–as much as $15,000. And one of the leaders of the Ukrainian TV-market airs a short jeans news story for about $50,000, according to one media manager informed about the situation on the station. Second-tier TV-channels may even offer a “season ticket” for a jeans series, costing as little as $6,000 for spots featured every week for a year (for example, this may involve regular reports on a company presenting computers or furniture to high schools boosting its corporate social responsibility credentials). If a client engaged in some political or business conflict wants to bring attention to his point of view, or a news story about his competitor not to be reported, or even to publish entirely fabricated “news”–that would raise the rates by 1.5 to two times, according to people in the business.

While news texts are published in a form close to originals prepared by the client’s marketing or public relations staff, analysis and opinion jeans stories are sometimes redrafted by editorial staff writers and published under their bylines, at a cost of $1,000 or so. Page one of a national newspaper goes for $5,000 to $50,000 depending on the circulation and what the “story” is about. A right-wing newspaper would charge more for giving space on their cover to Communist Party propaganda than to any national-democratic party–but it would run it. A large-scale two-to-three months long jeans media campaign consisting of materials repeatedly shown on television, broadcasted on radio, published in the online and printed outlets would cost around $60,000, these news executives say.

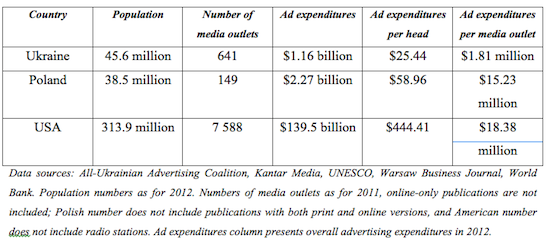

One possible reason for the prevalence of news corruption is that the pie of advertising expenditures in Ukraine is fairly small, and the media market is highly fragmented. Here’s how the country breaks down against a nominally similar Poland and also against the U.S.:

This structure probably impacts the media entities’ perception of the game they are playing: for most of them the ad-spend equivalent of reputation is tiny, and it is also highly dispersed as they share the blame with hundreds of other equally uninfluential participants (by the same token, those going against the wind of jeans have hard times trying to differentiate themselves and to capitalize on their fastidiousness).

As to the benefactors of jeans, IMI’s report accuses–by name–many incumbent politicians, including Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, first Vice Prime Minister Sergiy Arbuzov, head of Kyiv City State Administration Oleksandr Popov, of deploying jeans in their communications strategy. Members of Ukrainian parliamentary opposition do not shy away from jeans either: Mykola Katerynchuk from Yulia Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna faction regularly pushes own jeans materials into the media. Out-of-parliament opposition uses jeans too, with Viktor Medvedchuk and his pro-Russian movement Ukrainskyi Vybir among them. Communists are particularly fond of the jeans technology, sometimes ordering very expensive episodes on the leading Ukrainian TV-channels. One can not accuse them of inconsistency though, as far as decades-long Soviet traditions of meddling with media reporting are concerned. Generally, politicians avoid commenting on the jeans problem as it is not in the center of public attention, and when asked by journalists directly, they deny their own involvement.

Among business actors, as IMI calculates, the most active jeans users are alcohol producers (20% of the total), banks (20%), drug producers and medical service providers (11%), lotteries (6%), state-controlled Railway Administration company (6%). Lately, medium size businesses have been joining the bandwagon too.

Ukrainian political and economic analysts, who are often on the payroll of large political and business actors, have been deep into jeans practice too, many media managers and journalists say off the record. It is a role that sticks to the actor though: after an analyst crosses the line and starts jeansing his or her commentary and opinion pieces, media smell the money and become very reluctant to feature them later for free. And of course, the credibility losses, at least in the eyes of attentive observers, are substantial. The same logic applies to politicians and government officials: once they pay, media will often stop giving them floor for free.

Jeans’ biggest cost is, of course, the reputation of news organizations. “[The public] generally understands that too much positive information about some politician or businessman probably means it has been paid for,” says Natalia Ligachova, chief editor of Ukrainian online hub devoted to media industry Telekritika.ua. Obviously, a media entity cannot hope for the loyalty of its customers when the latter realize that they are being used. Thus, short-term profits come at a cost of long-term losses.

One important factor should also be emphasized: in general, major Ukrainian media are often more valuable to their owners as instruments of political influence than as stand-alone businesses. As a result, a lot of media outlets are dominated by oligarchs, who invariably have business interests that range far outside of media, with the latter serving subordinate roles in larger industrial conglomerates. For instance, country’s richest businessman Rinat Akhmetov owns Segodnya newspaper and Ukraina TV-channel, which are among the most popular Ukrainian media outlets; but his main businesses are in energy, steel and telecommunications. Ihor Kolomoyskyi controls 1+1 Media Group that includes several prominent TV-channels and online publications; and his business interests spread into the banking sector, metallurgy and oil extraction. Dmytro Firtash is an owner of Inter Media Group that is a major player on Ukrainian TV market; but his core businesses are in chemical, energy and titanium industries. Recently the list of such captured media has grown, as the largest independent market participant Ukrainian Media Holding, which has a strong presence in print, online and on the radio, has been acquired–at a premium price–by a business group with primary interests in banking and energy (this has already prompted many UMH journalists to resign).

At the same time, the dispersed Ukrainian media market also hosts a horde of minor independent players (hence media bazaar might be a more appropriate term), but for most of them reputation is not a valuable-enough asset to bring significant ad revenues, at least for the present. Future ramifications of decisions made today matter little in a country where the planning horizons of most businesses are ridiculously short even by emerging-market standards. Nevertheless, in the long-run, the media market, just like any other market, will reward suppliers that most efficiently satisfy the consumers’ demand. For media organizations, jeans should therefore be seen as a very expensive borrowing from the future.

And many journalists and others working in media fully appreciate the long-term consequences of wearing jeans. In an interview, Andrii Ianitskyi, Deputy Chairman of Independent Media Trade Union of Ukraine, says he hopes consumers will come to understand the need to pay adequately for quality information, generating a legitimate revenue stream and lessening the jeans temptation. He says it would also be helpful both if readers became more demanding and refused to buy publications pockmarked with jeans and journalists and even advertisers, too, stood against this shameful phenomenon.

Still many in media here are resigned to jeans. Oleksandr Chalenko, chief editor at news and opinions website Revizor.ua, says jeans have always existed in Ukrainian media market and always will. He sees them simply as a reasonable opportunity for our media and journalists to earn some money, and thinks in the future jeans, if anything, will just become pricier. Telekritika’s Ligachova says that jeans, regrettably, benefit all the main actors in the media market–from politicians to publications–and getting away with publishing “dirty” material is easy when there is so much on the market. But the IMI’s executive director Oksana Romaniuk sees hope in the fact that while jeans are not even noticed by the older generation, younger readers are more skeptical.

Indeed, there are some good reasons for optimism. Though initiators of jeans still tend to believe they work better than conventional ads, their effectiveness as an advertising method is actually doubtful. During the parliamentary elections of 2012, the newly formed Ukraine–Forward! party of a local second-echelon politician Natalia Korolevska has been a very active user of jeans, according to IMI, but such a strategy did not help them enter the parliament and brought only 1.58% of the vote. At the same time, another newcomer, a well-funded liberal party Udar, which gathered around Ukrainian heavy-weight boxing star Vitali Klitschko, as well as an older but much poorer right-wing party Svoboda were not noticed as heavy jeansers by the IMI. Yet, both demonstrated much higher than expected results, gaining 13.96% and 10.44%, respectively, and forming own parliamentary factions for the first time in their history.

Another good sign: a recent survey by two Ukrainian think-tanks, Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Fund and Razumkov Centre, shows that confidence in media among Ukrainian information recipients has been on the rise during this year. Why is hard to say. But given that this is happening at the same time when many influential media outlets and bright journalists have been particularly successful at producing resonant reporting and dramatic investigations, perhaps the improvement in confidence numbers is happening because slowly but steadily, those media that take the news seriously are winning out over those that go for the quick bucks.

Taking a bird’s eye view, jeans are evidence of Ukrainian democracy’s immaturity and stand in the same category as many people’s readiness to sell their votes during elections for cash or food. It may be the case that just like paid voting, jeans are also an intermediate station on the route to working democracy and rule-based free-market economy. However far from normal Western practices this is (and the West is not problem-free, of course), it may still be taken as a sign of progress considering the state of affairs in post-communist Ukraine. After the Orange Revolution, elites (policy-makers, oligarchs and such) finally realized that now they actually might need public support for what they do. Yes, jeans are a doubtful tool for these purposes, but they are still preferable to withholding the information completely and ignoring the attitudes of the sides involved.

In the future, it is only reasonable to expect that a growing maturity of Ukrainian voters and consumers in terms of democratic and market practices, as well as some consolidation of those dispersed media market participants that do not belong to large industrial conglomerates, will create an environment where good reputation will translate into larger subscription and paywall incomes along with higher advertising revenues, making jeans obsolete. There is a strong force at work here: readers are not going to tolerate being abused forever.

Here’s hoping the current protests are the push that’s needed for reform both in political and media spheres, as well.

Ivan Verstyuk is a senior editor at RBC-Ukraine, a member of the RBC business news agency that covers Eastern Europe. He is based in Kiev and can be reached at iverstyuk@rbc.ua.