Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In the months since OpenAI and other companies began releasing generative AI tools to the public, the technology has become the basis for jokes, apocalyptic fears, business models—and it has also become a highly contested front in copyright law, including for the news media.

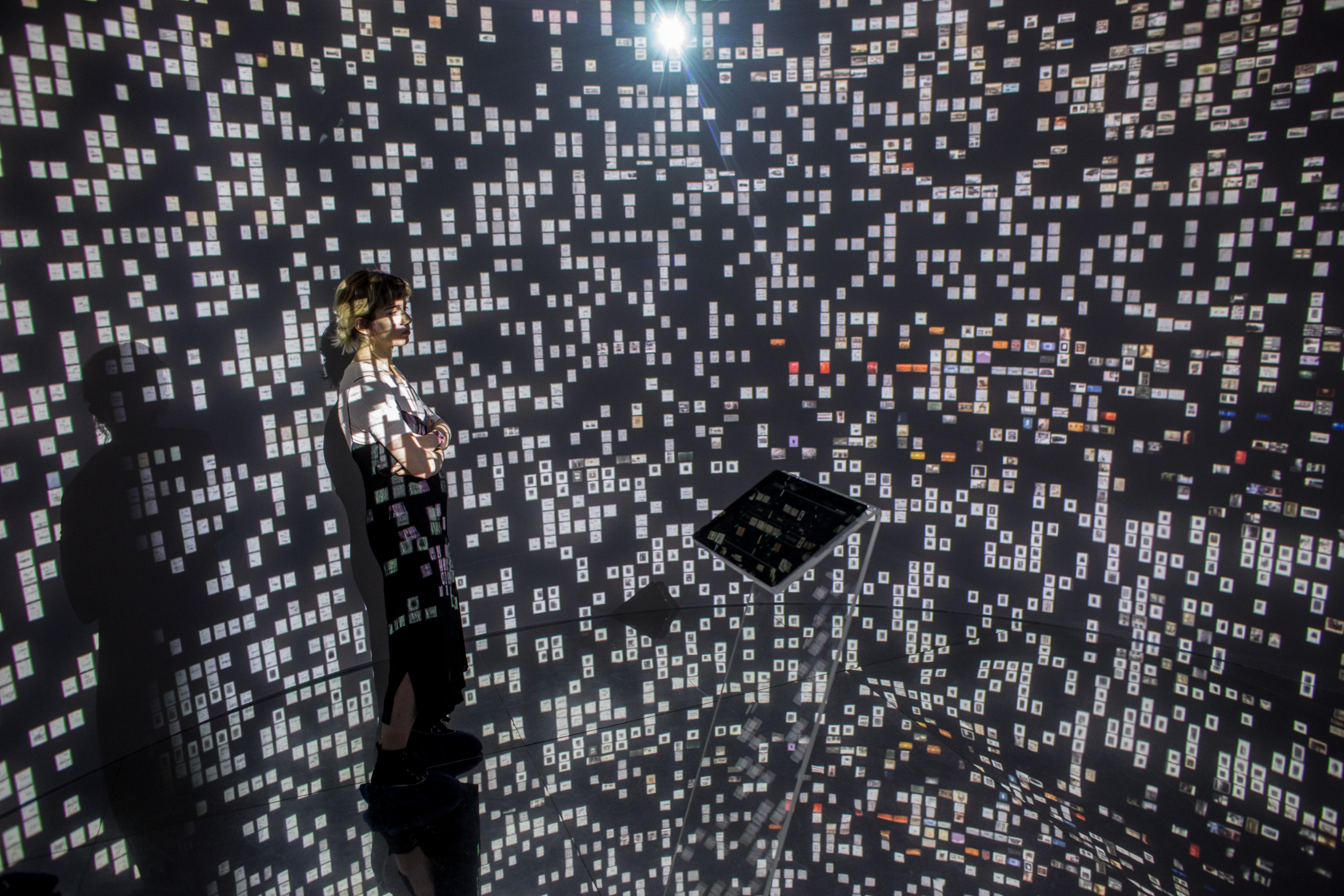

A step back: the thing we call generative artificial intelligence is, in fact, a kind of computing that looks for patterns in information and mimics them on command. To do this with any amount of coherence, the system must first be rigorously “trained”—fed absolutely enormous amounts of data to digest into a series of statistical probabilities. For an image-generating AI, this content includes millions of images. For a words-generating AI, it includes millions of words.

Several artists and authors have filed lawsuits over the use of their work in these training datasets. Karla Ortiz, a conceptual artist, is a plaintiff in ongoing cases against three image-generating services. “The creative economy only works when the basic tenets of consent, credit, compensation, and transparency are followed,” Ortiz said at a roundtable hosted by the Federal Trade Commission on October 4.

And, according to interviews with lawyers and media companies, as well as public statements from some of the key players, it may be an issue for the news media, too. We know for certain that at least some of the large language models (LLMs) behind generative AI tools—Open AI’s ChatGPT, Meta’s Llama, Google’s Bard—pulled from the copyrighted material of online publishers to train their systems.

The data on what material was used is ambiguous and fragmentary. But in addition to repositories of pirated books, research papers from Meta and OpenAI report that their models were trained in large part with data scraped by CommonCrawl, a nonprofit that essentially compiles data from public websites for use in research.

In 2021, the Allen Institute of AI ran an analysis based on a snapshot of CommonCrawl data. The Washington Post drew on this report to publish a searchable index of the websites scraped by CommonCrawl and used to train LLMs. The analysis revealed that half of the top ten Web sources were news outlets, including the New York Times and Los Angeles Times. (CJR was 13,420th on the list.)

What remains unclear is how the inclusion of this content could affect the news publishing industry—and what individual publishers will do about it. Tech companies maintain that their datasets are protected by the fair use doctrine, which allows for the repurposing of copyrighted work under certain conditions.

But Ortiz’s lawyer, Matthew Butterick, is not convinced by that argument. “Worst of all,” he said in an interview, “these language models are being held out commercially as replacing authors. There are instances already of AI-generated books being posted to Amazon, sometimes under real names, sometimes under fake names.”

In recent months rumors have circulated that several high-profile media companies might also bring the likes of OpenAI, one of the most prominent generative AI developers, to court.

During an interview at the Semafor Media Summit in April, Barry Diller, chairman of IAC, which owns the Daily Beast and People magazine, among many others, said that unless media companies are compensated for the use of copyrighted material, “all will be lost” for the industry. Diller argued that the practice is absolutely grounds for litigation, suggesting that companies should pursue legal action against OpenAI and others. (Later he seemed to soften that position.)

In June, the Wall Street Journal reported that companies including the New York Times, News Corp, and Diller’s IAC were considering forming a coalition to address the threats posed by AI. According to the article, one threat was that the ability of chatbots to respond directly to user queries could draw traffic away from publishers’ own websites, potentially diminishing ad and subscription revenue.

(In June, ChatGPT Plus users discovered that the chatbot’s internet search feature, Browse with Bing, could even bypass publisher paywalls directly when asked to reprint an article from a URL. The company temporarily disabled the feature “in order to do right by content owners,” which it said it did “out of an abundance of caution.” The feature was modified and made available again to paying users in September.)

According to Mehtab Khan, a lawyer and legal scholar at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Institute whose work focuses on copyright and internet law, filing a lawsuit at this stage would be a gamble. If the publishers lost, it could define training data for AI as fair use, which would close off an avenue for contesting the practice. So other options are also being explored.

The Times and a number of other outlets have indicated their desire to protect their copyrighted material with the addition of a line of code, robots.txt, meant to prevent Web scrapers from accessing their materials in the future (it does nothing to remove material that had previously been scraped).

In July, the Associated Press became the first news outlet to reach a licensing agreement with OpenAI over the use of some of its news content, effectively sidestepping court involvement and ensuring that the news agency would benefit from the use of its work.

Even as the industries work toward common ground, Congress and the FTC are involved in discussions around how copyright law applies in the training and use of AI. Their task, according to Khan, will be reframing existing ideas about how the fair use doctrine protects the public interest.

“There’s this fear that if text and data mining is restricted, if it’s not considered fair use, then there’d be too much power concentrated in the hands of large copyright holders,” she said. The key, she said, is to “find a balance that would allow the public to have access, but would also address some of the anxieties that artists and creative industries have about their words being used without consent, and without compensation.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.