Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

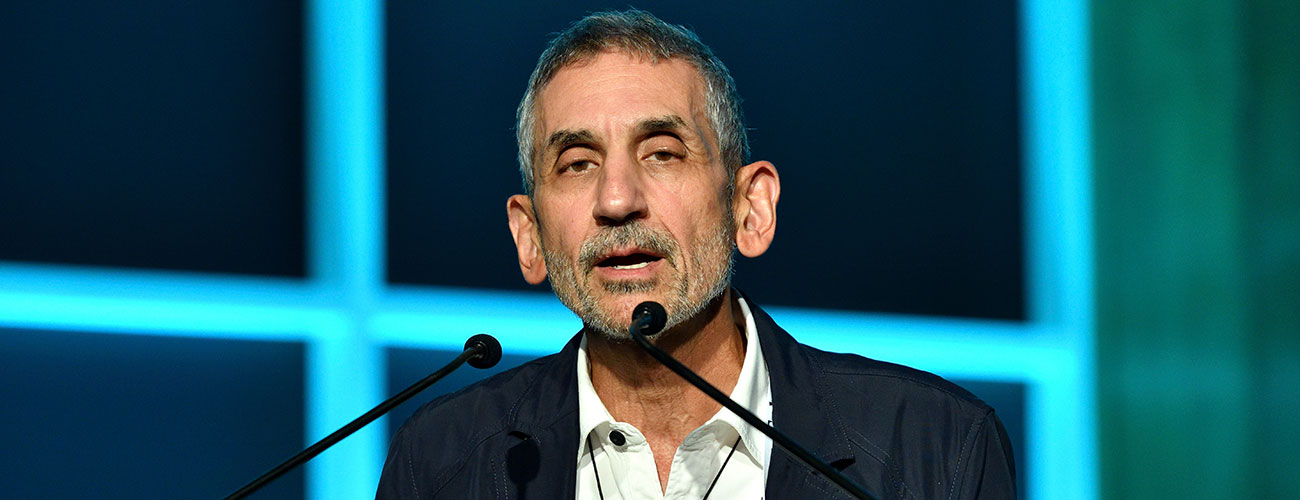

Lewis D’Vorkin’s voice is tranquil as he threatens his staff. The editor in chief of the LA Times explains slowly that someone in the newsroom isn’t playing by the “rules of ethical behavior.” Someone, he says in a recording obtained by CJR, is “morally bankrupt.”

He doesn’t name names.

For a man who often tells people his favorite movie is All the President’s Men, and claims to be “half journalist” and half businessman himself, the threat is incongruous. After all, he’s talking to a room full of reporters at one of America’s most respected, cherished, and recently besieged news outlets—an institution that won a Pulitzer in 2016 for reporting on the San Bernardino massacre. A newsroom at the moment busy covering the California wildfires, cases of police corruption, and the bewildering news cycle of the Trump administration.

ICYMI: Reporter exposes list that “ruined good people’s lives”

In early November, D’Vorkin gathered together over 100 journalists in the LA office not to congratulate them, or encourage them, but to warn them: This is his newsroom, and they will get on board. The threat is the final moment of the recording and follows a long-winded talk about himself. “You guys really don’t know much about me,” he explains on the recording, after describing a trip to LA’s art district, where he bought a painting of a typewriter emblazoned with the phrase, “Dream bigger.” “It might be good to know what I believe and what makes me tick.”

Getting to know Lewis D’Vorkin isn’t that easy, and neither is making sense of what exactly he has planned for the LA Times. In a nearly 44-year career, D’Vorkin, 65, has made few friends and many enemies. Even those who speak positively about him acknowledge he can be difficult, threatening, and, in the words of one writer who worked with D’Vorkin for more than four years and actually likes him, “without journalistic ethic.” And the successes that underpin his career, such as bringing an unpaid contributor model and branded content to Forbes, are among the very innovations that have helped bring media to a crisis moment. CJR interviewed more than a dozen journalists who once worked with D’Vorkin, many of whom refused to go on the record for fear of losing their jobs, talked to several journalists who currently work for him, and even visited his alma mater, the University of Iowa, to understand a man at the epicenter of media discord.

ICYMI: Reporter attends school meeting longer than other journalists. That ended up being a good decision.

After initially agreeing to an interview with CJR, D’Vorkin later declined to discuss his career or plans for the Times. With the exception of a couple of interviews, D’Vorkin has remained more of a figure behind the media than in front of it. The criticism and nicknames that follow in his wake have not yet impeded his path. What is clear about D’Vorkin is that he’s propelled by a love of buzzwords (gif is a current favorite) and an overriding ethos of change. LA Times journalists are probably wise to worry. Look no further than Stewart Pinkerton’s book, The Fall of The House of Forbes, which includes two chapters on D’Vorkin, who often wears black jeans, dark colored sweaters, and fashion sneakers. The first is titled, “The Prince of Darkness Part I,” and the second, “The Prince of Darkness Part II.”

Writer and editor Jeff Bercovici, the San Francisco bureau chief for Inc. who previously worked under D’Vorkin at Forbes, tells the story of a meeting where D’Vorkin told him: “Get shit done, because most people don’t.” Bercovici doesn’t remember what shit he wanted done and how. But D’Vorkin has a knack for quippy lines, often quoting movies to his staff, including lines from All The President’s Men, Network, and the romantic comedy Broadcast News. His speech is always polished, with few vocal fillers, no pauses, and no hesitation, which Bercovici says is evidence of his singular focus and drive. “[D’Vorkin] always has a lot of polished concepts that he can resort to,” Bercovici explains.

In the recent LA Times meeting, he also told his staff, “My goal is short, and it’s important: To combine the values and standards of traditional media with the dynamics of digital publishing.” On the recording, he goes on to explain the value in “pursuing a mobile future” and “flipping the script” and letting “mobile drive desktop and desktop driving print.” Such platitudes may have served him well at Forbes, AOL, and his Forbes-funded start-up True/Slant, but the LA Times is simmering with skeptical journalists who have seen significant editorial turnover in the past 10 years, just voted to unionize, and are tired of vague plans for a digital overhaul that go nowhere. Already, his newsroom has been more leaky than the White House—journalists aren’t taking his threats lying down.

Already, his newsroom has been more leaky than the White House.

There are audible sighs on the recording and perhaps a few punctuated sips of tea when D’Vorkin waxed about a “new” kind dynamic homepage that is “bold” and “conversational,” “newsy,” and “bright,” with “text that people can read.” And on this very different kind of homepage, D’Vorkin vowed to the staff of the LA Times, there will be breaking news, investigations, profiles, videos, graphics, and “gifs, gifs, all manner of media.”

Gifs.

Separately, in a November blog post that takes journalists to task for being wedded to print culture, D’Vorkin outlined a grand, confusing future with “a new more conversational tone; and visual storytelling that combines long-form text with the elements that mobile and social consumers want—video, photos, graphics, gifs and more.”

More gifs.

But a good gif is not a comprehensive vision. And it’s not even radical for the scope of the Times’s reporting and projects. Perhaps the new editor in chief hasn’t had time to familiarize himself with the (as of this writing) 298 custom web pages built for some of its stories. These projects include mobile-friendly layout, slideshows, and even the hit podcast Dirty John based on the long-form reported story, which is both conversational and bold (but sadly lacks gifs).

In another post, published in December, D’Vorkin criticized “newsrooms” (no one in particular, mind you) for not doing enough. He wrote:

Today, most visual storytelling on mobile news sites is desktop presentation shrunk to fit smaller screens through responsive design. That simply is not good enough in a world of social-sharing-minded consumers who want to tap out individual elements to friends rather than 1,000- to 5,000-word pages with embedded graphics and such. Staff structures will need to change to produce such news experiences.

One thing he suggested specifically was more stories that look like Instagram stories. And he linked to a story from Thrillist about 2017’s best new restaurants as an example of what the Times should aspire to.

ICYMI: Journalists have something new to worry about in February

That story from Thrillist looks a lot like the stories on the Times projects pages. It’s just that Thrillist was writing about restaurants instead of the California fires or a con man preying on women. But okay, the Times also wrote about 2017’s best restaurants, which included an interactive map.

D’Vorkin’s exhortation to the newsroom that produced all of this?

With reluctance, traditional newsrooms accepted the desktop and laptop revolutions in theory, if not practice. To grow and prosper and to serve new audiences in a mobile world, reporters and editors must do more than talk the talk. They need to reinvent themselves.

Bercovici explains that D’Vorkin has always been like this. “He’s not a happy talker kind of guy who’s going to come into an organization he thinks isn’t working and say everything’s great, everyone’s getting a raise. That’s not his style at all,” says Bercovici.

As a result, D’Vorkin’s leadership has stirred up controversy. An early run-in with the newsroom came after news surfaced that Disney had banned the Times from advanced screenings as punishment for an investigation into the company’s business ties to the city of Anaheim that alleged an almost incestuous relationship between the company and the city that houses it. (The story included embedded video, mobile responsive design, and an interactive chart illustrating Disney’s campaign contributions to various PACs. Truly a coup for a newsroom still married to print.)

The New York Times reported, “During a daily meeting attended by roughly a dozen editors, a staff member proposed publicizing the two-part investigative series that had precipitated the ban. But Lewis D’Vorkin, the recently installed editor in chief of the Times, flatly rejected the idea, according to several employees with knowledge of the discussion.”

According to The New York Times, journalists were warned over Slack not to share the first New York Times story on social media. On November 7, after those warnings and a meeting with D’Vorkin, Disney agreed to end its ban of the paper. According to The New York Times and sources within the LA Times newsroom, journalists believed that the D’Vorkin-enforced social media blackout was part of D’Vorkin’s deal to woo Disney to end the ban.

“It might be good to know what I believe and what makes me tick,” D’Vorkin told his staff.

It wouldn’t have been the first time D’Vorkin had eased the worries of a big company at war with journalists. In August 2017, journalist Kashmir Hill wrote about her time at Forbes, where she was pressured to unpublish a story about Google’s PR bullying tactics. Her boss at the time: D’Vorkin. When reached for comment about the story, Hill said she had written all she intended to say about the situation.

In a piece for Gizmodo published in August 2017, Hill wrote, “I was told by my higher-ups at Forbes that Google representatives called them saying that the article was problematic and had to come down. The implication was that it might have consequences for Forbes, a troubling possibility given how much traffic came through Google searches and Google News.”

Hill ultimately pulled the story due to what she phrased as “continued pressure from my bosses.” Hill declined to offer more insight on the story, but this implication of business before ethics has his new staff worried.

D’Vorkin’s warning to his staff comes at a time of upheaval for the newspaper. In 2016, Chicago entrepreneur Michael W. Ferro, Jr. took over Tribune Publishing and announced he would turn the paper into a “global entertainment brand.” In August 2017, he installed CEO and Publisher Ross Levinsohn and interim Executive Editor Jim Kirk to replace Davan Maharaj, who had been criticized for stonewalling important stories and bleeding the paper of talent.

Levinsohn hired D’Vorkin in October 2017, and D’Vorkin brought with him a reputation as the media equivalent of a house flipper—making cosmetic changes to gussy up a brand for some quick cash. At Forbes and at his Forbes-funded startup True/Slant, he performed his media remodel by instituting a contributor model, where writers were paid according to the volume of their traffic, and sometimes not at all. The scheme flooded Forbes with content, a swath of it of suspect quality and journalistic value, but enough to boost traffic and entice an Hong Kong firm, Whale Media Investments, to buy Forbes for an undisclosed amount in July 2014. In an interview with CJR, Mike Perlis, former CEO of Forbes, states that D’Vorkin’s changes saved the magazine.

A writer who worked with D’Vorkin for several years agrees. “[D’Vorkin] took over Forbes at a time when search and social was a nice, new growing stream of traffic, and then it became the whole thing, and the ad networks took over all of digital advertising,” explains the writer. “The tide that lifted the boat eventually swamped it. I don’t know. I don’t know how anybody solves that problem.”

So if D’Vorkin gets credit for raising the tide with his push to expand the contributors at Forbes, he should also be blamed for sinking the boats. And so far, it looks like he’s taking a similar approach at the LA Times, with a my-way-or-the-highway attitude, plus gifs, plus a contributor model.

If D’Vorkin gets credit for raising the tide, he should also be blamed for sinking the boats.

At a recent presentation to the Needham Growth conference, Levinsohn outlined a new contributor model for the newspaper. He described the model in a slideshow as (buzzword alert), “[A] network of deep micro-niche vertical ‘entrepreneurs’ and their audiences.” That same model also outlined branded content as a key element going forward. So basically: D’Vorkin’s tired, old Forbes model repurposed for the LA Times.

It’s also worth noting that amid all of this change Levinsohn has recently taken an unpaid leave of absence from the LA Times, after a report by NPR correspondent David Folkenflik found that Levinsohn was a defendant in two sexual harassment cases.

Looks like Tronc is launching a contributor network, according to this presentation our publisher gave today. "Over time, emphasis shifts to more audience-targeted, self distributed and cost-effective models." https://t.co/EemCzRVZPf pic.twitter.com/G2Q2suatml

— Matt Pearce 🦅🇺🇸 (@mattdpearce) January 18, 2018

Meanwhile, the actual innovator of the contributor model, The Huffington Post, just announced its plans to drop that approach and focus on quality journalism.

D’Vorkin grew up in Long Branch, New Jersey, the oldest child of Abraham and Gloria D’Vorkin. His father ran D’Vorkin & Sons salvage yard. He graduated from Long Branch High School in 1971 and attended the University of Iowa, where he served as the editor in chief of the student-run paper, The Daily Iowan.

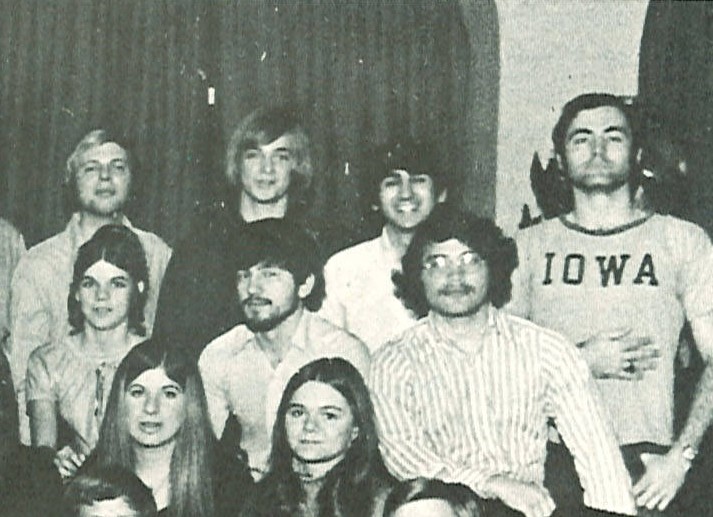

Lewis D’Vorkin, pictured with his dorm floor, top row, second from the right. The picture is from the 1972 University of Iowa Hawkeye yearbook.

The year D’Vorkin was a freshman in college, the journalism program and the paper were caught between the forces of progress and traditionalism. Leona Durham, who served as editor of the student paper during the 1970-1971 school year, temporarily lost her job as the editor because she’d been seen at a anti-war rally on campus. She was reinstated when an advisory panel of professors ruled in her favor.

“Before the paper had been controlled by the university,” Durham tells CJR. “They didn’t like me.”

After Durham, a panel of students and faculty picked more staid editors. “They wanted company men,” explains Durham. Was D’Vorkin in that category? I asked Durham. “Absolutely,” she replied.

D’Vorkin became editor in chief of the Daily Iowan in 1973, two years after Durham. He graduated with high distinction from the University in 1974 with a BA in economics and journalism. His first job out of college was with Dow Jones newswire, which began an early career inside the big names of media—The New York Times, Newsweek, and The Wall Street Journal.

From archives: Politico embarrasses WSJ

On his LinkedIn profile, D’Vorkin gives his title at The New York Times as “Enterprise Editor, Sunday Editor.” A representative from the Times noted that their files indicate he was employed as, “Assistant to the Editor – Business.” When reached for clarification, D’Vorkin wrote in an email, “I joined the NYT as a Business Day copy editor. I was promoted to the backfield as assignment editor and then enterprise editor. I then became deputy to the Sunday Business editor, Soma Golden.” Golden did not respond to CJR’s request for an interview.

At the Journal, D’Vorkin was hired to be the Page One editor in 1987, a job he held for six months before he left and filed for personal bankruptcy. According to a 2010 profile of D’Vorkin in the Observer, he had reportedly misused his expense account. The bills were from Brooks Brothers, Lord & Taylor, Saks Fifth Avenue, and Tiffany.

“He wasn’t terribly popular. I don’t think he would deny that.”

A New York Times story from 1988 about D’Vorkin’s bankruptcy notes, “Mr. D’Vorkin’s bankruptcy filing listed personal debts of about $129,000, said a spokesman for Dow Jones & Company, which owns the Journal. Those debts include an unspecified sum owed to Dow Jones. The largest debt is about $45,000 owed to American Express, the spokesman said.”

A New York Times story about his resignation noted, “Mr. D’Vorkin ruffled some feathers when he replaced Glynn Mapes, his popular predecessor, who had been Page One editor for 12 years…” Journalists complained that D’Vorkin went too far as an editor—jazzing up their stories beyond what they were comfortable with. The Page One staff, writes Pinkerton, “…felt D’Vorkin was pushing traditional Journal standards of taste too far.”

Even the people who liked him note that he wasn’t well liked. Glynn Mapes, who worked with him at The Wall Street Journal in the late 1980s, says, “He wasn’t terribly popular. I don’t think he would deny that.”

D’Vorkin surfaced later that year at Ziff Davis Enterprise, where his LinkedIn page says he worked as editorial director. Then he joined USA Today (working on the USA Today television show). He founded a magazine, Virtual City, which was designed to be a print-based guide to the online world. It never made it past the fourth issue. From there, D’Vorkin worked at Forbes and was later recruited by Jonathan Sacks, who was president of AOL Interactive Services, to work at AOL. At AOL, he explained in an interview on Digital Riptide, “I went on as the editor of what then was the welcome screen. Went on to run news and sports and entertainment, and run AOL.com.” There, he either launched (according to his LinkedIn page) or relaunched TMZ.

In June of 2008, D’Vorkin left AOL and founded True/Slant. The site was funded by Tim Forbes, and later acquired by Forbes. True/Slant was a small-scale knockoff of The Huffington Post, borrowing heavily from the model of contributor networks. Except here they were paid, more or less. Contributors were paid traffic bonuses and high-profile writers were given more, while some just did it for the exposure.

Writers worked day and night; sometimes D’Vorkin would bring up cookies from the coffee shop on the floor of the building below. According to Michael Roston, who worked for D’Vorkin at True/Slant, D’Vorkin could be encouraging, especially to writers he liked. But more often than not he was in meetings while his staff churned out content—hitting publish first, editing later. Roston estimated the site was generating a million monthly unique visits every month for the last six months the site was up.

ICYMI: A newsroom was told by management to run a “vile” editorial. Staffers made a bold move.

Forbes acquired the site in 2010. What they got was a content mill, which they folded into their site, and D’Vorkin, who became chief product officer. There were some snafus, of course—after the site was acquired by Forbes, stock promoters wrote self-promoting stories and one writer called the president of Ireland an “acknowledged homosexual”—but there was also traffic. Before long, D’Vorkin’s hands-off editing with a scrum of motley contributors began causing trouble for Forbes.

In September of 2010, the magazine published a story titled, “How Obama Thinks,” by Dinesh D’Souza. The article was inflammatory and riddled with errors, causing the White House to push back. Forbes eventually added a small correction at the beginning of the Web version of the story. The blame for the article was shifted to Steve Forbes, who was editor in chief of the magazine at the time, and people familiar with the story noted that it was Forbes who pushed for it. Yet, as Perlis explains to CJR, “Ultimately, all editorial decisions ran through the organization that reported to Lewis.”

In response to the story, The New York Times noted, “In one sense, the episode was a cautionary tale for the new media age, which finds traditional media outlets like Forbes responding both to the economic imperatives of the digital age by cutting staff and to the editorial imperatives by bringing in more outside voices—Mr. D’Souza is not a staff writer—and sometimes elevating opinion above rigorous reporting.”

And also, rigorous editing—an element often overlooked in D’Vorkin’s newsrooms. By all accounts, D’Vorkin has never been a hands-on editor. Even back in his early days of journalism, beyond shutting down an idea, or tweaking a lede or a headline, writers doubted he even read the content.

He’s always been a big-picture guy—someone more concerned with the overall spread of the magazine than the day-to-day minutiae of fact-checking stories for accuracy. “Speed is the new accuracy,” Pinkerton quotes D’Vorkin as saying.

Beyond shutting down an idea, or tweaking a lede or a headline, writers doubted he even read the content.

Some writers liked the freedom. Journalists who found favor in D’Vorkin’s eyes were supported in their work, no questions asked. Bercovici explains, “If you were aligned with him, he removed a lot of the clutter and bullshit that makes it hard to do your job in most places. I really appreciated that. I felt like he understood what I needed to do my job well, and tried to give me the tools and tried to take away everything that was getting in my way.”

To them, he was warm, and friendly, even fatherly. But the rest of the writers were afraid of him. A true “Darth D’Vorkin,” as the New York Observer noted in 2010.

It’s a fitting metaphor for his authoritarian rule over the newsroom. As Pinkerton writes in The Fall of the House of Forbes,

The long-time Forbes journalists who spent years doing substantive multisource stories, being told to blog in a chatty “cocktail party voice” is inherently offensive…These staffers felt they were in a sort of purgatory, a transitional period of purifying punishment where the pain comes not from the fire but from a dumbed-down world of sound bites, workers being flayed to turn out more hits, demands for tweets, a loud Babel of finger-waving ideologues, and the moans of those ordered to write about Paris Hilton.

D’Vorkin is a job hopper who has stayed afloat in part by embracing change at all cost, or at least talking a good game about it. He spent four years at The New York Times, four years at Newsweek, four at AOL, and even less time at other places. As a result, Perlis and Pinkerton hail him as a pioneer of change.

Yet Ken Doctor, the media analyst and author of Newsonomics: Twelve New Trends That Will Shape the News You Get, says D’Vorkin’s legacy is more complicated. “D’Vorkin brought the contributor model and the idea of branded content to a legacy magazine, so in that sense he is a pioneer,” Doctor tells CJR. “But they weren’t his ideas, and I don’t think he’d say they were.”

One thing has stayed the same: Confusion reigns in the newsrooms he takes over, and D’Vorkin tends to make enemies quickly. The 2010 “Darth D’Vorkin” profile in the Observer notes of his entrance at Forbes, “One high-level editor who has been with the paper since the ’90s said that while there seems to be a clear strategy for the magazine, the staff isn’t clear on how it will affect them. ‘I don’t know if I would use the word bewilderment,’ the staffer said. ‘It’s kind of unclear even at this stage, when he talks about turning people into bloggers, self-promoters and everything, does that mean us? Where do we editors and reporters fit in?’”

Swap out “bloggers” and “self-promoters” for “gifs” and “mobile-driven,” and the quote could have as easily come from an editor at the LA Times.

Another former staffer who worked with D’Vorkin at Forbes for four years and also asked not to be named, calls D’Vorkin’s editing style mercenary, more concerned with what will get attention and what will work for the audience than the accuracy and import of the writing itself.

A second former staffer notes, “His overriding ethic is to do whatever he has to do—he’s a chameleon—whatever fits the moment.”

Another staff member at the LA Times shared a December 10 email from D’Vorkin praising the newsroom for hip hop coverage in the lifestyle section. The big story on the front page from the day before? An explosive investigation into police misconduct at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. (In the email, he specifically called out the gif—a black hat that reads “NWA” and a swinging gold chain.)

“His overriding ethic is to do whatever he has to do—he’s a chameleon—whatever fits the moment.”

Mapes, who worked with D’Vorkin at Page One, and others say that D’Vorkin has an instinct for what will encourage clicks. It’s a skill that’s good for business, but not always aligned with the values of journalism. Others describe his skills as a disruptor. Perlis explains: “Lewis is a change agent, and when you’re a change agent and you’re bold and you are decisive, everything is not always smooth.”

Jeff Jarvis, a professor at City University of New York’s Graduate School of Journalism, has called Forbes’ brand diluted. Writing in 2015, Jarvis outlined the perils of the contributor model, explaining:

In Forbes’ case, the brand and company were dying when Lewis D’Vorkin arrived with a solution. He used the brand as candy to attract more than a thousand contributors to supplement a few score editorial staffers, reducing the average cost of content to near nil. Though I’m all in favor of publications opening up to new voices, it must be said that this tactic reduced the average quality of Forbes content.

A long-time Forbes staffer says the initial excitement of change buoyed many journalists upon D’Vorkin’s arrival, but the buzzwords soon wore thin: “Lewis always said the right things—every quarter we had celebrations, with big cakes with Warren Buffet’s face on it, celebrating our new accomplishments. He was good at giving speeches and telling us revenue was up. But soon, it was a running joke in the newsroom that literally once a quarter he would have a ‘game-changing’ idea for journalism.”

D’Vorkin spent a lot of money on his ideas, and it began to chafe. “He talked about how the future was in mobile and spent so much on these cutesy mobile graphics. Meanwhile, amazing reporters were fleeing the magazine,” the former staffer explains.

There were other problems, too. A 2014 article in Fortune accused contributors of accepting payments in exchange for stories about stocks, an unethical pay-for-PR scheme that Forbes still can’t shake. In 2016, The Outline published a story exposing the rotten underbelly of the contributor model: contributors at Forbes taking payments to write about companies and products.

The gentleman who enabled this apparent practice at Forbes now sits atop the @latimes. https://t.co/kYpe923uNi

— David Folkenflik (@davidfolkenflik) December 5, 2017

For his part, D’Vorkin sees online news as a different animal than print. “The editing process online is vastly different than in print,” he said in a 2010 interview for the Observer. “There is a fit and finish that you must have in print. Online, it’s not about fit and finish; it’s about the flow of information, the updates of information. It’s about relevance and timeliness. It’s not about craftsmanship. Quality online does not equal craftsmanship. In print, quality does equal craftsmanship.”

Contributor models have given conspiracy mongers, fake news, and advertisers the cloak of respectability all for the price of clicks. But Perlis dismisses these concerns, noting, “If, with a couple thousand contributors, from time to time a line is crossed, we deal with it very swiftly and keep the credibility and the quality of our content strong by doing so.”

“The legacy that Lewis leaves here is one that has us proud of being innovators and accomplishing a great deal that other companies have not been able to accomplish. In large part, I give credit for that to Lewis,” lauds Perlis.

ICYMI: NPR drops a major scoop

And if journalism is a business, as D’Vorkin writes in his 2013 e-book The Path Forward for the News Business, one of two e-books he self-published through Forbes Media, then, the contributor model was a success. Not a success of journalism but a success of economics. In 2014, the once-floundering media company was deemed successful—selling a majority stake to a Hong-Kong investment company in a $475 million deal. Not bad for a four-year turn around.

At the LA Times, D’Vorkin is adjusting his approach, but not by much. He has written two blog posts outlining his vision for pulling the newspaper into the future, and lectured his newsroom on the importance of understanding how the editorial, and tech, and product, and sales come together. The contributor model probably is not far behind. And Levinsohn, who is currently on a leave of absence, has said he wants to build the paper into a global entertainment brand with a dominant entertainment vertical. “[Ferro] bought The Daily Meal [a site that bills itself as all things food and drink],” explains Doctor. “[Levinsohn] tried to buy US Weekly. Levinsohn and D’Vorkin are clearly focused on building a strong vertical.”

“The real question here is, is the model to build big and get page views even relevant anymore?” Ken Doctor asks.

But Doctor questions the relevance of that model in 2018: “The real question here is, is the model to build big and get page views even relevant anymore? If you look at any successful media start-up, the focus is on quality over quantity. But D’Vorkin innovated the reverse model. Can he adapt?”

Doctor continues: “Another issue is that the survival of media depends on building a subscriber base, which means having loyal fans and producing the content that loyal readers want. And if D’Vorkin is a change agent, are his changes going to motivate that base or alienate them? What is new in D’Vorkin’s bag of tricks?”

Doctor doesn’t answer his own questions. And neither does D’Vorkin.

But with Levinsohn’s recent announcement about contributor networks and branded content, it appears Doctor isn’t too far off: D’Vorkin’s vision is just same old media dressed up in new buzzwords.

Oh, and also gifs.

ICYMI: The New York Times made a decision that infuriated readers

Correction: This article has been updated to clarify that the “snafus”—in which stock promoters wrote self-promoting stories and one writer called the president of Ireland an “acknowledged homosexual”—occurred after True/Slant was acquired by Forbes, and to clarify the nature of the cases against Levinsohn as harassment, not assault. The piece also previously identified the buyer of The Daily Meal as Levinsohn. It was Michael J. Ferro, Jr.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.