Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Ted Young faces the glass wall of his office and asks me what I see.

“A newsroom?” I answer, puzzled. He looks disappointed, so I elaborate uncertainly. “Uh, people working?”

“What are they all staring at?” he says with a classic British mélange of irritation and impatience, then brightens to answer his own query: “Their screens! They’re going to spend eight or nine hours looking at their screens at work today.”

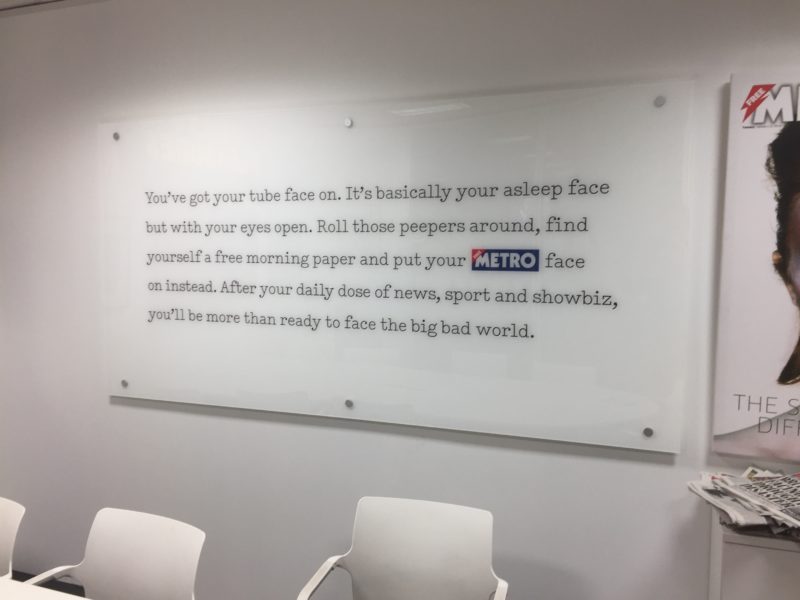

Young, the 55-year-old executive editor of British tabloid Metro, is offering a theory for why his publication is a runaway success with millennial readers. It already has the United Kingdom’s highest readership, according to the National Readership Survey, and this summer it is expected to become the country’s largest-circulation newspaper.

It’s free, yes, and that helps for a generation unaccustomed to paying for their news and information. But Young believes there’s something more at play: “Before people go to work, it’s actually quite nice not to have to look at a screen, to have a product that you actually don’t have to download, don’t need WiFi for, don’t need to scroll, doesn’t have ads that pop up in front of your face. There are certain advantages of paper.”

Advantages of paper? In 2017? Evidently so.

Metro, founded in 1999 by DMG Media, parent company of the Daily Mail, now boasts a print run of more than 1.47 million a day, up from 1.3 million in 2014, when it started being monitored by the Audit Bureau of Circulation. As Metro grows, circulation is dropping at The Sun, Rupert Murdoch’s legendary tabloid and longtime British newspaper champ. The Sun ended 2016 with a weekday print run of 1.6 million, half what it was in 2010, and it has since fallen below 1.5 million to hold a slim 30,000-copy lead over Metro as of February’s audit figures. (Metro is not affiliated with the free commuter tabloids of the same name published in some East Coast cities in the US.)

RELATED: Print is dead. Long live print.

“People still pick up Metro despite the army of technology being thrown at them,” Metro circulation chief Paul Lamoureaux says. “They’re still picking up, reading Metro, and engaging with a physical product.”

Metro is popular, Young insists, because it knows exactly what it is: A breezy, photo-heavy 60-page rundown of the day’s top stories delivered to more than 2,500 locations aimed at folks taking “the tube in London, the tram in Edinburgh, the buses in Glasgow and Manchester.” Stories average just 300 words and, in the edition being planned the day I visited, ranged from the sensational tale of a swingers’ sex club being run out of a row house to a heart-tugging piece about the high cost of care for dementia patients. The covers, as would be expected from a tabloid, feature what in another format would be dubbed “clickbait”; for the next day’s edition, it would be an item about three burka-clad women, purportedly ISIS combatants, appearing in court to face charges connected to a thwarted London knife attack. “That, I think, is clearly the biggest story today,” Young told me that afternoon.

Stories average just 300 words and ranged from the sensational tale of a swingers’ sex club being run out of a row house to a heart-tugging piece about the high cost of care for dementia patients.

“I try to at least give people a rounded view so that when they get to work, they’re informed,” says Young, noting most content comes off the wires because his news desk consists of six journalists including an editor. “It’s people like The New York Times, The Washington Post, they’re the ones who’ve got the resources to go out and really break stories. My job is to inform people in as responsible a way as possible what is going on in as entertaining a way as possible.”

To be sure, Metro carries healthy doses of entertainment items and sports coverage, and Young says he’s beefed up the political news content because he’s noticed an uptick in interest. “Brexit, I think, has had a huge effect of making a lot of younger people more interested in politics because a lot of people didn’t bother to vote and then they suddenly said, ‘Oh, how did that happen?’”

RELATED: In a tabloidized world, tabloids struggle

Lamoureaux says Metro’s core reader, per ABC audits, is between 18 and 44 and has a full-time job, a demographic that “nobody else gets anywhere near. If you’re advertising around a young, upwardly mobile audience with a high disposable income, we’re it.”

Yet once those readers get to work, Metro essentially relinquishes them until the next morning’s commute, rather than aggressively chasing them all day online. Metro.co.uk drew an average of just 1.7 million unique visits in April 2017, a tenth of its print readership and seventh nationally, ABC reports. Its corporate sibling, The Mail, by contrast, led the nation with 15.1 million uniques, and The Sun came in No. 5 with 4.8 million.

https://www.gettyimages.com/license/527553654

While most major papers have integrated their Web and print operations to the degree that online placement of stories is as much a focus of daily editorial meetings as the next morning’s print lineup, at Metro that doesn’t even come up. The only references to any internet operations during the news meeting I attended in early May came in a brief report about the amount of time readers had spent with various parts of the two daily digital editions—a record combined “dwell time” of 29 minutes during the prior week that has since risen to over 30 minutes, thanks in part to the introduction of new puzzles. One e-edition of few days earlier was downloaded 30,000 times, digital content chief Simon Garner brags, before ticking off a few other data points.

“The stuff about the new Watergate, the FBI firing by Trump, got us 45 seconds, which is a long time for a top story,” Garner says. “Also getting 45 seconds was that crazy nurse story. Our audience loved that.”

None of those figures seems particularly impressive, although he also was excited to note Apple News had picked up as a lead item a Metro digest of what to look out for in the next day’s news. “Ah, I should’ve taken a [screen] grab, I’m sorry,” he told Young.

“I would imagine you would have even fewer people bothering to pick up the Metro when there’s good internet reception below ground.”

Young, who served for two years as online editor for the New York Daily News before returning to London to take the helm of Metro in 2014, finds it liberating not having to worry too much about all that.

“We as journalists are constantly trying to feed the beast online, get the next story, get the next analytics, get SEOs so you’re ahead of the rest,” he explains. Focusing too much on what’s happening on the Web, he says, can leave editors with a mistaken impression of what readers already know and what they should. “Sometimes the readers aren’t keeping up with it as much as you think they are,” he says.

In British journalism circles, few are impressed by Metro. Its success is attributed in equal measure to the simplicity of its content and the fact that it’s free. While acknowledging Metro is “the only paper you see anyone reading on the train in the morning,” Suzanne Franks, head of the journalism department at City University of London, had little complimentary to say about it otherwise.

“It’s a very, very low-grade effort, really,” she says, griping that the paper’s refusal to take editorial stances is one reason it feels “colorless compared to most papers. Because it’s free, people take it, and it’s there. It has a very good distribution system, but nobody would pay for that.”

Young disputes the notion people will pick up the paper just because it’s free, citing a recent experience when he was at Heathrow Airport on a Saturday evening, picking up his wife. A news vendor was offering the weekend edition of the Financial Times, normally about $4.50, for free, but few people took copies.

“There were great piles of them that nobody wanted,” Young says. “Just because it’s free, you should not underestimate the intelligence of the reader. If it’s a rubbish product, they’re not going to pick it up. They’ll pick it up once and then they’ll say, ‘I’m not reading that again.’ We give them something they’ll want every morning to pick up and say, ‘Right, I’m going to read this on the way to work.’”

The test of Metro’s durability, Franks says, will come if the London Underground ever provides better, reliable access to data or WiFi for devices.

“It only works as a commuter paper where they can’t get internet and that’s all there is to do,” she says. “I would imagine you would have even fewer people bothering to pick up the Metro when there’s good internet reception below ground.”

TRENDING: Six rare images that capture Trump’s TV addiction

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.