Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

When Enrique Rivas became mayor of the Mexican border town of Nuevo Laredo last October, the city’s small El Mañana newspaper turned its attention to covering his administration.

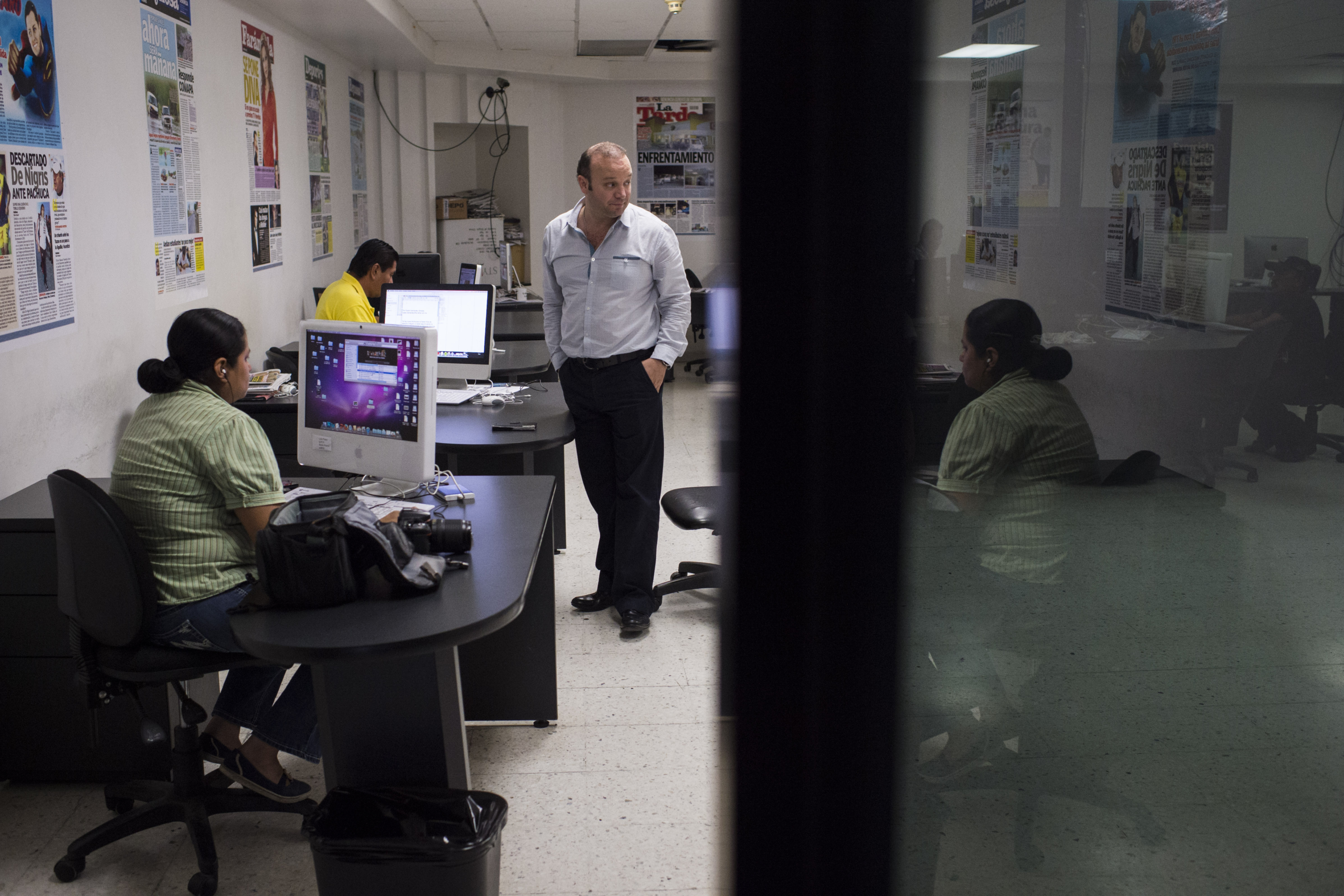

In the pages of the 93-year-old daily, which circulates some 15,000 copies on weekdays, reporters detailed everyday stories of local politics: Rivas had appointed women to key cabinet positions, discussed an eight-lane expansion of the World Trade Bridge with the mayor of Laredo, Texas, and talked about the city’s pothole problem.

They also made other observations. One article noted that a handful of Rivas’s family members and friends had been tapped to serve in his administration. Another used documents obtained through the country’s transparency law to show that a former police officer with a criminal record had been awarded a lucrative government contract. And a third took note of the municipality’s 120 million peso ($6.6 million) budget for communications and publicity.

ICYMI: While on air, authorities grab journalist and violently drag her on the ground several feet

That did not please the denizens of city hall. “We’re not going to allocate public resources to people who are mercenaries of information,” Rivas said at a news conference in May. He also announced his administration had retracted all official advertising from the pages of El Mañana, saying the newspaper had tried to extort 2.5 million pesos per month in exchange for positive coverage.

The only option they have is to live on what the government gives.”

In a phone interview, Mauricio Flores, assistant managing director of El Mañana, “categorically and unequivocally” denies the mayor’s allegations. “We see it as an abuse of authority that the mayor used the state apparatus to defame a news outlet,” he says. “The newspaper has never put its editorial content up for sale,” he adds, saying that Rivas sought retribution for the newspaper’s critical coverage of his administration.

For well over a decade, violence has afflicted Mexico, known as the most dangerous place to be a journalist outside a war zone. Since January alone, at least four journalists have been murdered, while nearly 100 have been killed in the country since 1994, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. But while physical aggression and impunity have stifled news coverage, the practice of awarding or withholding government advertising in exchange for editorial influence has functioned as another threatening form of censorship.

Official advertising is an ingrained part of Mexico’s media landscape. According to one report by the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers and the Center for International Media Assistance, half or more of local media budgets come from government advertising, which is frequently distributed based on political leanings. In one case the association took note of, the respected political weekly Proceso received more than 74 pages of federal government ads in 2006, but just seven in 2009 after it published negative articles about then-President Felipe Calderon.

In the absence of more commercial advertisers and given the decline of the classified section, however, many outlets depend on the government subsidy. “The only option they have is to live on what the government gives,” says German Espino, a professor at the Autonomous University of Queretaro who studies the intersection of politics and media.

In 2015, state governments in Mexico spent 11.9 billion pesos on communication and publicity— paid content that resembles news, full-page transcripts of government speeches, spot ads on radio and TV—while the federal government spent 10.2 billion, according to civil organization Fundar, which studies budget issues in Mexico. Such figures fuel claims of corruption. While some media owners and poorly-paid reporters temper reports just to survive, others readily collude with political figures or create phantom outlets to capture funds. According to a 2017 study published in the Global Media Journal, an estimated 63 percent of non-daily publications listed in state media directories exist in name only.

Hardly any outlet is immune from this form of government influence. In 2014, the most recent year for which Fundar analyzed data, television broadcasters Televisa and Azteca received roughly half a billion pesos each in government advertising, representing some 26 percent of all federal resources spent on communication and publicity. Grupo Radio Formula received more than 61 million pesos and leading Mexican newspapers Reforma and El Universal took in a combined 73 million pesos, Fundar noted, highlighting a system of financial assistance that has existed since the days of Mexico´s one-party regime, which lasted until the election of Vicente Fox in 2000.

During the seven-decade rule of Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party party, outlets rarely strayed far from the official line. When advertising revenue was not a sufficient incentive, wrote Chappell Lawson in Building the Fourth Estate: Democratization and the Rise of a Free Press in Mexico, other incentives were used. “Tax forgiveness, subsidized utilities, free service from the government-owned news agency Notimex, bulk purchases by government agencies, credit at below market rates, and cheap newsprint,” he wrote, “were all rewards for suitably pliant periodicals.”

Despite assurances from Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto that he would regulate the use of publicity when he was elected president in 2012, legislation has yet to establish criteria for the distribution of government advertising or rein in public spending on communications and publicity.

“[Peña Nieto] wants the discretion to use state funds to keep the press in line, especially since he is so embattled,” says Sallie Hughes, a professor of journalism and Latin American studies at the University of Miami, referring to the president’s approval rating, which has plumbed new lows in the last year.

ICYMI: How the ‘alt-right’ checkmated the media

Adding to the complicated picture, she notes, some journalists view the use of state ad funds as normal. “Critical media representatives say they have circulation so they deserve the allotments as part of legitimate state ad campaigns,” she says.

Pena Nieto’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

The only solution is that official publicity stops existing.”

While federal government spending on press activities has been public information since 2012, many consider the information recorded too vague and outdated to be useful. Other reforms that could regulate advertising and limit media concentration have not been implemented. Some argue that even increased oversight would not be a perfect fix. “The only solution is that official publicity stops existing,” says Raul Trejo Delarbe, a political science professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

For now, Flores, the assistant managing director of El Mañana in Nuevo Laredo, says that the mayor’s public criticism, combined with cartel violence in the restive state of Tamaulipas, puts the newspaper in a precarious position.

In 2004, El Mañana’s editorial director, Roberto Mora, was found in front of his house with more than 25 stab wounds. The newspaper’s office has been subject to multiple attacks by gunmen over the years. And in January, it stopped circulation for two days, citing threats made against its employees. “We wrote the newspaper, we printed our newspaper, but that was it,” Flores says, declining to give further details because of safety concerns.

The mayor’s decision to pull advertising and openly criticize the paper does not help.

If drug-traffickers see that the local government no longer supports the newspaper, Flores says, it “opens a door that makes us even more vulnerable.”

“Obviously it worries us.”

ICYMI: “If you’re telling me his secrets, you’re probably telling him mine. Now I know never to trust you.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.