Late last week, there was a fair bit of online chatter (see here, here, here, and here) about an unlikely subject: an academic paper that’s cluttered with terms like “Bayesian heteroskedastic ideal point estimator” and “standard homoskedastic estimators” (and that’s just in the abstract). But for all that intimidating tech-speak, the paper (PDF), by Princeton Ph.D. candidate Benjamin Lauderdale, was engaged with a question that’s of recurring interest to the press: Just who are the most “maverick” politicians? And what makes a politician a maverick, anyway?

The logic of Lauderdale’s approach is actually pretty straightforward. Members of Congress can be plotted, according to their votes, on a liberal-to-conservative scale. For most legislators on most issues, their position on that scale will predict their vote pretty well.

There is a subset of legislators—those who are economically liberal and socially conservative, or vice versa—who deviate from this pattern, and who sometimes get branded as “mavericks” in the press as a result. But Lauderdale notes that if you introduce a second axis, you can predict their votes pretty well too. (He also helpfully distinguishes between mavericks and moderates: a conservative Democrat or liberal Republican who occasionally votes with the other side still occupies a stable place on the liberal-conservative spectrum.) Instead, he introduces another way to identify mavericks—as the lawmakers whose votes don’t reflect any of the standard perspectives in electoral politics, or, as he puts it, who display “voting driven by factors orthogonal to those that influence most legislators.”

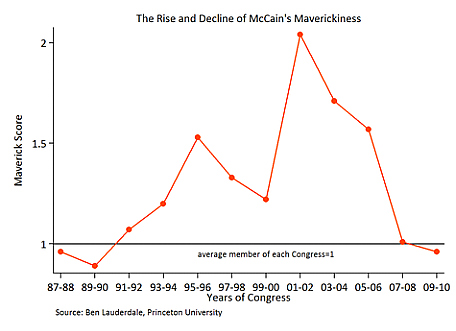

This is all conceptually interesting, but it’s doubtful anyone outside the academy would have heard of it if John Sides of The Monkey Cage hadn’t used Lauderdale’s data to test the status of the best-known maverick of recent times, John McCain. The result has been making the rounds:

This is consistent with the qualitative account of McCain’s trajectory, which is that he became somewhat mavericky after the GOP takeover of Congress in the mid-90s, got more conventional as he ran for president, found his maverick tendencies rejuvenated during his fit of pique after losing to George W. Bush (this is when the McCain-Feingold campaign finance law, which sealed his maverick status, was passed), and has been getting more orthodox ever since, to the point where he’s more or less become a conventional Republican.

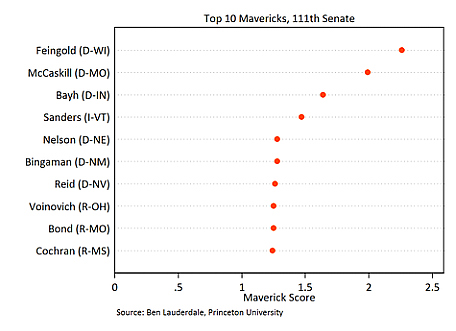

But Sides also did some other interesting stuff with the data, including building this graph of the most mavericky members of the 111th Senate (that’s the one in session now):

One of the notable results here is the predominance of Democrats at the top of the list (although Harry Reid’s position is the result of tactical voting for procedural reasons). Another notable outcome: the absence of South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham, who, as CJR has previously noted, has repeatedly been tabbed as McCain’s successor as D.C.’s Top Maverick.

Maybe that’s a small-sample size result—we’re not even through the session, after all. How about the 110th Senate, for which Sides did not build a graph but did provide a top-10 list?

1. Feingold (D-WI)

2. Voinovich (R-OH)

3. Hagel (R-NE)

4. Reid (D-NV)

5. McCaskill (D-MO)

6. Byrd (D-WV)

7. Gregg (R-NH)

8. Kyl (R-AZ)

9. Coburn (R-OK)

10. Bayh (D-IN)

No Graham there, either. That was as far back as Sides went in his post, but over email, Lauderdale provided a little more information:

Graham has not really shown any maverick tendencies in his voting over the last three Congresses. He is reliably between the 10th and the 20th most conservative Senator, and he votes quite predictably as such. Perhaps if climate change or immigration legislation comes to the floor, we might start seeing something though.

So what does all this mean for press coverage of this subject? Well, it’s another indication that, as Matthew Yglesias says in his post, in political discussion “a lot of terms get bandied about that lack rigorous definitions.” It’s possible to argue for definitions of “maverick” other than the one Lauderdale offers: there’s more to legislating than casting votes, after all, and Graham’s readiness to engage on issues like climate change has been genuinely significant. Still, his “maverick” standing seems to have come as much from a media-friendly approach and a personal relationship with McCain as an actual record. It’s maverickiness by association.

It’s also a sign that the press loves a maverick—they signify both unpredictability and a willingness to turn against regular allies, two things that make for great copy—and will create one of it has to, which, in an era of high partisan polarization and strict party discipline, it may. Graham’s maverick status, after all, is now imperiled because of a dispute over whether and when to bring climate change and immigration legislation forward, but as poor a maverick as he makes, there aren’t many good alternatives among the Republicans.

On the other hand, maybe that’s just as well. One of the all-time historical mavericks, according to Lauderdale’s methodology, was one William “Wild Bill” Langer, whose biography is titled, natch, The Dakota Maverick. Here’s how Lauderdale describes his career:

…Langer (R-ND) had been removed from office as governor of North Dakota after a felony conviction for fraud in 1934, an episode that led to Langer (temporarily) declaring North Dakota independent of the U.S. and barricading himself in the state house with a group of armed supporters. His popularity resilient, Langer was re-elected Governor in the following election, and then elected to the Senate in 1940. Langer was sufficiently controversial that the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections recommended that Langer not be seated 13-3, but was overturned 52-30 by the full Senate. During his legislative career, Langer opposed Lend Lease, NATO, and the Marshall Plan. Unlike most Americans (senators included), Langer was no fan of Winston Churchill, “in 1951, when the former British Prime Minister visited the U.S. Langer sent a telegram to the pastor of Boston’s Old North Church requesting that two lanterns be placed in the belfry to warn Americans that the British were coming.”

Maybe the “M” word shouldn’t be used as a compliment, after all?

Greg Marx is an associate editor at CJR. Follow him on Twitter @gregamarx.