The other day, President Trump delivered an unexpected outburst about changing the nation’s libel laws. This is what he said:

Our current libel laws are a sham and a disgrace, and do not represent American values or American fairness. So we’re going to take a strong look at that. We want fairness. You can’t say things that are false, knowingly false, and be able to smile as money pours into your bank account … I think what the American people want to see is fairness.

Let’s try to unpack this statement. What steps is he going to take?

First things first. “We’re going to take a strong look at [the fact that] our current libel laws are a sham and a disgrace.”

ICYMI: The real reason why journalists love to hate the new Trump book

Trump doesn’t seem to know, here, that libel laws are a state issue, and that he, as the head of the federal executive branch, doesn’t have much say in the matter. The federal government is involved only to the extent that the Supreme Court has laid down guidelines putting limits on state laws when they do not pass constitutional muster.

“There is no federal libel law, period,” observes Floyd Abrams, one of the nation’s foremost authorities on the issue. “All American libel law is state law.… Each state can adopt whatever libel law it wants, as long as it comports with the US and state constitutions.”

“And the”—he pauses to laugh—”musings of President Trump about doing something about libel runs into that first, and then of course, runs into the First Amendment because of the ruling in New York Times against Sullivan, which is really what upsets him.” (More on that in a moment.)

What about the president’s contention that authors can say “things that are false, knowingly false, and be able to smile as money pours into your bank account”?

The specific issue Trump was complaining about here is actually at the very heart of libel law.

Abrams was making reference to The New York Times vs. Sullivan (1964), the Supreme Court’s most important ruling on libel.

ICYMI: Trump might be in serious trouble for his NBC tweets

In Sullivan, the court said the press must be able to make mistakes and not be unduly punished for them. However, the court also said that a public figure could win a libel judgment if the material published was false—in cases where the entity publishing it knew it wasn’t true, and published anyway.

One would think the president would know something about libel laws before he started tweeting about them.

He was either asserting something he knew wasn’t true …

… or recklessly making assertions about something without checking whether it was true.

One could make the argument that he was essentially libeling the nation’s libel laws.

But he said this doesn’t represent the nation’s values.

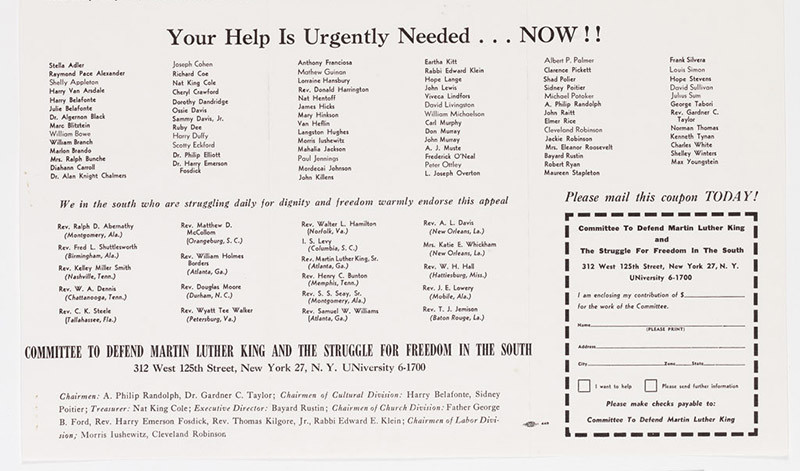

The Sullivan case has an appropriately confused history. It wasn’t about a news story. It was based on an advertisement that was published in the Times. The ad was calling for donations to the Civil Rights Movement, and it cited an “unprecedented wave of terror” directed against black students in Montgomery, Alabama.

(The full image is here.)

This ad was not a perfect poster child for the First Amendment. A number of details it stated were factually inaccurate, and the man who brought suit wasn’t even named in the ad. Lester Sullivan was a town commissioner of Montgomery at the time, with authority over the police. He contended that the word “police” referred to him. The Alabama courts awarded him $500,000, a large sum in the ’60s. (Abrams says this was part of a pattern of large libel judgments in the South designed to punish reporting on Civil Rights battles.) The Times appealed to the US Supreme Court.

ICYMI: A “potentially seismic” change comes to Facebook

The unanimous decision was written by Justice William Brennan. Brennan noted a “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open, and that it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

In other words, according to the Supreme Court, libel laws do contribute to “American values.”

But Trump has also said he thinks the British system is better. It’s easier to sue for libel in the UK.

It is certainly true that the British do not share American values when it comes to free speech; the British do not have a First Amendment.

But the framers of the Constitution were familiar with British Common Law, which included libel protections and probably did not intend it to displace them.

Here’s one argument James Madison made for the First Amendment. He pointed out that Britain’s government was based on royal power—kings who could as a matter of definition do no wrong. See if you can catch the rather dry irony in this polysyllabic observation:

The nature of governments elective, limited, and responsible, in all their branches, may well be supposed to require a greater freedom of animadversion than might be tolerated by the genius of such a government as that of Great Britain.

Animad-what?

It’s a fancy word for tough commentary, or for getting someone’s attention. Madison is saying this: “Hey, if you’re ruled by a king, who needs free speech? Doesn’t matter anyway—and what a great system you guys have over there!” But a republic needs an informed citizenry, and you don’t want information being cut off in any way, and particularly not cut off by the government.

Abrams notes that loose contemporary British libel laws make publishing in the UK more perilous. They also created a condition where politicians almost have to sue.

“One of the realities in the US [is that] it’s very unusual for public officials to bring libel suits,” Abrams said. “It’s the norm in England. There, the press says, If you don’t bring a libel suit, it must be so. The absence of a libel suit is taken in English society as a concession of truth.

“That’s never been the case here. More recently, it has provided a sort of excuse-slash-explanation for politicians. They say, I can’t sue because American libel law makes it so tough to win.”

What about appointing Supreme Court justices who will take a tougher line on libel?

That might take some time. The trouble is that the conservative judges Trump is likely to nominate are hardline on the First Amendment.

“This has been a very, very pro-First Amendment court in my view,” says Abrams—”more of a First Amendment court than it may ever have been in American history. In the last few decades, the conservatives on court have adopted a very broad reading of the First Amendment.”

So there’s nothing Trump can do about libel?

Well, there’s one thing. Trump libels people more than most. He said for many months that Barack Obama’s birth certificate was false, contrary to all evidence. He repeated it even when told it wasn’t true, and, when he did finally withdraw the accusation, he did so incompletely and grudgingly. That’s an example of a half-hearted retraction—something that’s been often used as foundation for a libel judgment.

Trump also said the Obama administration had wiretapped his campaign. As the now head of government, he can easily find out if that’s true. But he chooses not to, and he has recently repeated the claim. That’s evidence of recklessness.

In a recent Wall Street Journal interview, Trump accused an FBI agent of treason for criticizing him before he was elected, in private text messages.

So Trump could improve the libel climate in the country simply by libeling others less frequently.

ICYMI: Headlines editors should be very proud of

Bill Wyman is the former arts editor of NPR and Salon.com. Follow him @hitsville.