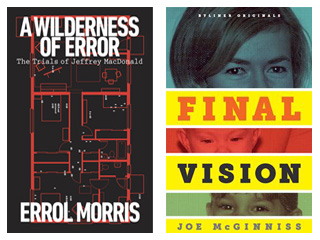

A Wilderness of Error: The Trials of Jeffrey MacDonald | By Errol Morris | Penguin Press | 544 pages | $29.95

Final Vision: The Last Word on Jeffrey MacDonald | By Joe McGinniss | Byliner, Inc. | $2.99

In 1970, 26-year-old Colette MacDonald and her two daughters were found stabbed to death in their Fort Bragg, NC apartment. Colette’s husband, 26-year-old Army doctor Jeffrey MacDonald, claimed that a band of hippies, including a girl with long blonde hair and a floppy hat, burst into his apartment and murdered his family. He was acquitted by an Army tribunal, retried by a civilian court, and convicted of murder in 1979. He has spent the last 33 years proclaiming his innocence from a prison cell.

In his new book, A Wilderness of Error, filmmaker Errol Morris sets out to prove that Jeffrey MacDonald is, if not an innocent man, at least a victim of the criminal justice system. Morris is best known for The Thin Blue Line, a documentary that got an innocent man off death row. This September, a New York Times book critic raved that A Wilderness of Error would leave the reader 85 percent convinced of MacDonald’s innocence.

In his new book, A Wilderness of Error, filmmaker Errol Morris sets out to prove that Jeffrey MacDonald is, if not an innocent man, at least a victim of the criminal justice system. Morris is best known for The Thin Blue Line, a documentary that got an innocent man off death row. This September, a New York Times book critic raved that A Wilderness of Error would leave the reader 85 percent convinced of MacDonald’s innocence.

In Morris’s telling, MacDonald is also a victim of unscrupulous journalism. In 1983 journalist and author Joe McGinniss published Fatal Vision, which would become the definitive popular account of the MacDonald murders. Morris argues that Fatal Vision distorted the facts of the case and poisoned public opinion against the doctor.

MacDonald has every reason to loathe McGinniss. In 1979, MacDonald made McGinniss a full-fledged member of his defense team in exchange for a cut of the book’s future profits. McGinnis even lived with MacDonald and his lawyers at a frat house in North Carolina. Over the course of the trial, and during his jailhouse correspondence with MacDonald, McGinniss became convinced that MacDonald was guilty, but he kept telling MacDonald that he thought he was innocent. MacDonald only learned otherwise when Fatal Vision was published.

(Update, 01/08/13: This afternoon, Joe McGinniss left a message on my Facebook page clarifying his original arrangement with Jeffrey MacDonald’s defense team. McGinniss writes: “MacDonald’s lawyer realized that prosecution could subpoena me during trial and force me to testify about inner workings of defense. Being a journalist did not provide immunity. To eliminate the risk he paid me one dollar and named me ‘investigator.’ It was a ruse, and not necessary because prosecutors had no interest in me. Obviously, I did no investigating for the defense. My role was clear. But for many years after The Selling of the President, some people thought I’d worked for Nixon. Since I left the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1968, except for a couple of teaching gigs, I’ve never worked for anyone but myself.”)

Last month, McGinniss released an ebook called Final Vision: The Last Word on Jeffrey MacDonald. In it, he summarizes the post-conviction history of what has become the longest-running criminal case in US history and explains why Morris’s claims of startling new evidence are really old news. McGinniss scoffs at Morris’s claim that Fatal Vision sealed MacDonald’s fate, noting that the book came out after the doctor was convicted and that the courts began rejecting MacDonald’s appeals before Final Vision saw the light of day.

Read side-by-side, A Wilderness of Error and Final Vision amount to a journalistic sumo match in which two heavyweights grapple for control of the MacDonald narrative. In order to assess Morris’s book, we must lay out the case made by the prosecution at trial and reported in Fatal Vision.

Jeffrey MacDonald looked suspicious from the outset. He was in the apartment that night, and he was a Green Beret, trained to kill hand-to-hand. He was barely injured, and injured in ways that could have been self-inflicted, or inflicted by his wife, Colette, in self-defense. His cover story was preposterous. “Drug-crazed hippies killed my family” is “The dog ate my homework” of murder.

Upon closer examination, MacDonald’s cover story didn’t match the physical evidence at all. For example: He claimed he was attacked in the living room, where he held up his pajama top to ward off the blows of an ice pick-wielding hippie. According to MacDonald, after being clubbed unconscious, he awoke to find the attackers gone and his wife dead on the floor of the master bedroom. MacDonald said he covered his wife with his ripped pajama top before going to check on the girls. Yet investigators found no pajama fibers in the living room—meaning it couldn’t have been ripped there, as MacDonald claimed—and lots of pajama fibers and threads in the master bedroom, including several under Colette’s body.

Even more damning, a lightly soiled pajama pocket flap found near Colette’s body shows that she bled directly on it before it was ripped off. The area covered by the flap was soaked in blood, so we know the flap came off first. One sleeve was bloodied before it was ripped down the seam. The defense didn’t even try to dispute this evidence at trial.

Morris breezes past the inconvenient pajama threads and blood spatter. As far as he’s concerned, the whole crime scene was hopelessly corrupted. Everyone agrees that the military police lost control of the scene but that doesn’t explain how Colette bled on the top before it was torn, or how those threads ended up under her body.

Morris spends a lot of time trying to discredit a model the prosecution used to show that MacDonald stabbed his wife’s corpse 21 times through his own pajama top, creating 48 holes in the garment. Morris discounts the simulation because it relies on unsupported assumptions about how the top was draped over Colette’s body. If Morris is right, the prosecution’s model should be downgraded from incontrovertible proof of MacDonald’s guilt to highly plausible conjecture. But even if we throw out the prosecution’s pajama model, the rest of the fiber and blood evidence still points squarely at MacDonald.

MacDonald claimed that he attempted CPR on his daughters, even though they were both obviously dead when he found them. Yet his daughters, 5-year-old Kim and 2-year-old Kristy, were found on their sides with their mouths closed, posed as if they were sleeping. If he’d actually performed CPR on the dead children, they’d have been on their backs with their mouths open. We know Kim’s body was moved after she was mortally wounded because her blood and cerebral spinal fluid were found in the master bedroom. The fact that blue pajama fibers were found under her bedclothes suggests she was moved by someone wearing her father’s pajama top.

There are many, many more instances where MacDonald’s story conflicts with the physical evidence. And yet the jury might still have been inclined to believe the doctor—if they hadn’t also heard about the outlandish lies he told about the case. (He told his father-in-law and a family friend that he located, tortured, and murdered one of the intruders, for example.)

So why is Morris willing to believe that MacDonald might be innocent? Basically, because MacDonald seemed like such a good guy. Morris simply can’t believe that a Princeton-educated Green Beret doctor who was widely regarded as a loving husband and father would do such a thing. He thinks it’s perfectly plausible that a bunch of hippies would decide to attack a Green Beret for no particular reason, but he can’t imagine that MacDonald might have a dark side.

Morris also believes MacDonald might be innocent because of the confessions of local drug addict named Helena Stoeckley. Stoeckley was one of scores of Fayetteville-area hippies who were questioned in connection with the MacDonald case. At the time, she was a 17-year-old runaway who supported her omnivorous drug habit by working as a police informant. When her handler asked her if she knew anything about the murders, Stoeckley, still tripping, said she “felt in her mind” like she was there.

Stoeckley’s handler asked her about the murders because she sometimes wore a blonde wig and a floppy hat, like the one MacDonald described.

A military policeman saw a young woman with long hair and a wide-brimmed hat standing on a corner near the MacDonalds’ home as he rushed to the scene. Neither the officer nor MacDonald could identify Stoeckley from a photograph, however.

For years, Stoeckley alternated between confessing to anyone who would listen and swearing she didn’t remember anything. When she was finally called to testify at MacDonald’s trial, she said she was so high on mescaline that she had no idea where she’d been.

Morris suggests that Stoeckley knew things she couldn’t have known unless she was in the house that night, but these claims are unconvincing. Stoeckley was interrogated so many times over the years, and the case received so much publicity, that it’s impossible to know which details she picked up from her interrogators. Like many who trust Stoeckley, Morris tends to seize on what she got right—when she got it right—and forget about all the errors and wildly implausible claims she made over the years. Morris omits Stoeckley’s most outlandish “confessions,” such as her claims that she applied to babysit for the MacDonald children, burglarized their house three weeks before the murders, and got high and had sex with Jeffrey MacDonald.

Morris makes a big deal out of the fact that Stoeckley passed various polygraph tests, which suggests she was sincere. As a champion of the wrongfully convicted, Morris should know that false confessions are surprisingly common. An estimated 15 to 25 percent of cases reversed by DNA evidence involve some kind of false confession or guilty plea. False confessions where the subject comes to believe the false narrative are unusual but hardly unheard of. Stoeckley had many risk factors for one of these so-called internalized false confessions. She was young, drug addicted, hallucinating on the night in question, suffering from a personality disorder that made it difficult for her to distinguish between fantasy and reality, and eager to please her police handlers.

Of all the claims of judicial misconduct in A Wilderness of Error, only one stands out as being both serious and credible. Morris suggests that Stoeckley clammed up because one of the prosecutors threatened to charge her with murder if she testified to being in the house that night. If Stoeckley had confessed and the prosecutor hadn’t told the defense, he would have been withholding exculpatory evidence, a serious form of misconduct. Morris takes it one step further and suggests the prosecutor’s behavior was akin to witness tampering.

Morris’s case centers on a 2005 affidavit from a now-deceased US Marshal named Jimmy Britt who claimed to have transported Stoeckley from South Carolina to North Carolina to testify. Britt swore that Stoeckley confessed to him en route and later to the prosecutor in a closed-door meeting. He claimed the prosecutor threatened to charge her if she told the truth.

At the evidentiary hearing in September 2012, after A Wilderness of Error had gone to press, the government demolished Britt’s affidavit. McGinniss enumerates the many defects of the document. The paper trail proves that Britt didn’t transport Stoeckley from South Carolina and that he was never alone with her for any extended period of time. It’s doubtful that Britt was in the meeting between Stoeckley and the prosecutor; US Marshals don’t usually do that. The prosecutor denied both that Stoeckley confessed to him and that Britt was in the meeting. Stoeckley told the judge that she gave the same story to both sides. We know she didn’t confess to the defense, because Joe McGinniss was there and reported the meeting in Fatal Vision. With that, Morris’s only substantial case for miscarriage of justice crumbles.

The most dramatic moment in Final Vision comes when McGinniss recalls his realization during the 2012 evidentiary hearing that MacDonald’s lawyer lied to the trial judge during a tête-a-tête at the bench in 1979. The lawyer claimed that Stoeckley said all kinds of incriminating things in their pretrial meeting to which she later refused to testify. McGinniss reported in Fatal Vision, and reiterated in Final Vision, that Stoeckley said nothing of the sort.

As McGinniss explains in Final Vision, most of the putative miscarriages of justice that Morris cites in his book have been exhaustively reviewed by appeal courts and rejected. A pattern emerges. The defense got the original crime scene investigation file through a FOIA request, and they’ve since insisted that every scrap of debris that can’t be traced to something in the house is proof of invaders, proof that should have been turned over to them earlier.

Morris doesn’t give us enough information to assess the procedural merits of their claims. Just because MacDonald’s lawyers say evidence should have been turned over to them doesn’t mean that they were entitled to it, let alone that the prosecution committed malfeasance by not turning it over. One might infer from MacDonald’s more than 30-year losing streak that his case lacks merit; but Morris considers it further proof of the system’s bias against MacDonald.

As far as the probative value of the “withheld” evidence, it’s pretty much a bust. Any occupied home will contain hairs and fibers that can’t readily be sourced, especially transient housing like the MacDonalds’ apartment.

In 2012, the defense shamelessly trumpeted the results of DNA testing released in 2006 as “new evidence” of MacDonald’s innocence, even though none of the three untraced hairs matched Helena Stoeckley or her boyfriend Greg Mitchell, whom she named as an accomplice.

Morris tries to blame McGinniss for poisoning the well against MacDonald, but Fatal Vision mostly reported the facts as they were presented at trial. The disappointing truth is that MacDonald was proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in 1979 and his lawyers have been grasping at straws ever since. Joe McGinniss’s Final Vision should indeed be the last word on the subject.

Lindsay Beyerstein is a freelance journalist in Brooklyn and the co-host of the Point of Inquiry radio show and podcast