Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Images from Afghanistan have always revealed the truth behind the notion that the American war was on solid footing. We may have been told, since it first began shortly after September 11, 2001, that significant progress was just around the bend. But the pictures showed something else.

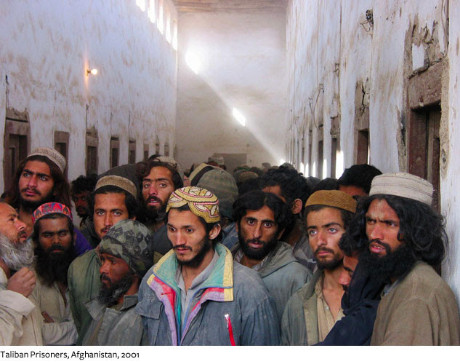

In November 2001, five thousand Taliban fighters surrendered to US-allied Afghan troops of the Northern Alliance in Kunduz. At least two thousand are believed to have either been suffocated to death or shot in container trucks by those allies. The survivors were held at the Sheberghan prison––a facility built for closer to a thousand inmates––where this picture was taken on December 29 or 30 by photojournalist Alan Chin.

In 2009, a New York Times article by Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter James Risen revealed new evidence that the Bush Administration impeded at least three federal investigations into alleged war crimes in Afghanistan, beginning in 2002. Despite seven years of investigation by human rights groups, the United Nations, and investigative journalists, not enough evidence could be secured to declare the events in Kunduz a war crime.

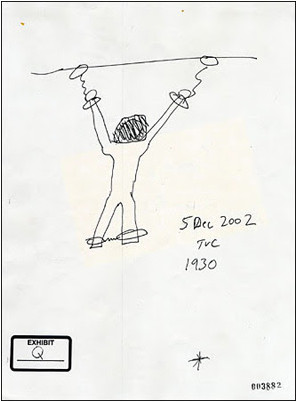

This drawing illustrates the torture of a taxi driver named Dilawar in December 2002 at Bagram Airforce Base. He was detained on December 5, 2002, and died five days later. It was included in over two thousand pages of Army documents detailed by the New York Times. The interrogation regiment at the facility included torture, beatings, and humiliation. Dilawar died of blunt force injuries to the lower extremities.

According to the report, a military intelligence specialist, Staff Sgt. W. Christopher Yonushonis, who participated in the interrogations, later told an agent of the Criminal Investigation Command that, “by the time Mr. Dilawar was taken into his final interrogations, ‘most of us were convinced that the detainee was innocent.’”

This is one of a series of portraits of active-duty US soldiers made by artist Susan Opton. All the portraits were taken in 2004-5 at Fort Drum, New York after the soldiers had returned from Iraq or Afghanistan, awaiting redeployment. The photo is titled: “Claxton: 120 Days in Afghanistan.”

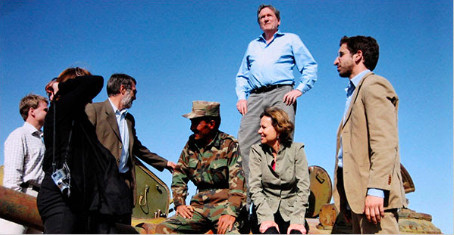

This family photo accompanied an article in the New York Times, profiling President Obama’s new envoy to Pakistan and Afghanistan, Richard Holbrooke. It shows him standing on a tank in Herat, Afghanistan, in 2006 above his wife, Kati Marton.

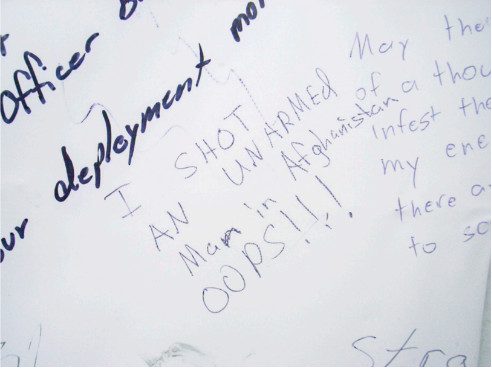

For a decade and a half, Magnum photographer Peter van Agtmael documented the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. In 2007, he documented graffiti of US soldiers on the bathroom walls at the Al Salem Air Force Base in Kuwait, a major traffic point for American troops.

Tim Hetherington’s 2008 World Press Photo-winning image of a shocked and exhausted US soldier seemed to crystallize the pathos and dysfunction of the war. Like so many other images he took of the war, including the widely-seen Sleeping Soldiers series, it also calls out the theme of masculinity.

David Guttenfelder’s photo for the Associated Press, taken on May 11, 2009, in the Korengal Valley, was touted at the time as the iconic photo of the Afghan war. Both the media and the Pentagon made light of Spc. Zachary Boyd fighting the Taliban in his “I Love NY” boxer shorts. Defense Secretary William Gates wrote at the time:

“Any soldier who goes into battle against the Taliban in pink boxers and flip-flops has a special kind of courage … I can only wonder about the impact on the Taliban. Just imagine seeing that: a guy in pink boxers and flip-flops has you in his cross-hairs. What an incredible innovation in psychological warfare.”

The US spent trillions of dollars to pay for the war and to prop up the Afghan government. In September 2008, in light of escalating civilian deaths from US attacks, Gates issued new rules dictating that Americans would quickly apologize and compensate survivors, even in advance of formal investigations. In the image, we see a woman who lost her husband and two of her children in a US airstrike the following year. She is being compensated by officials at the local governor’s office.

This photo, taken by veteran photojournalist João Silva for the New York Times, speaks to both in the most literal terms. In October 2010, Silva himself stepped on a land mine while on patrol with US soldiers in Kandahar and lost his left leg below the knee, and his right leg from just above it. He wears two prostheses and is still a Times staff photographer.

Anja Niedringhaus created an impressive body of work in Afghanistan and Iraq. She was killed at the age of 48 by an Afghan policeman while covering the country’s 2014 presidential election. This photograph, which happened to be taken on September 11, captures a patrol southwest of Kandahar in 2010 and symbolizes how out-of-step the western incursion was with the culture of the country. The Canadian coalition soldier in the foreground chases a chicken just seconds before the unit was attacked with grenades shot over the wall.

In 2010, US Army General David Petraeus broadcast that the US had been holding secret talks with the Taliban. Soon after, this photo came out showing Petraeus and the US Ambassador in Kabul, Karl Eikenberry (far left), walking with that contact, Alim Fedayee (in sunglasses). Fedayee was one of the most senior commanders in the Taliban movement and also the Governor of Maidan Wardak Province.

But the man who purported to be Fedayee––along with the man alleged to be the Education Minister Farooq Warda Mohammad (hands clasped)––turned out to be an imposter.

David Gilkey’s image features Lance Cpl. Anthony Espinoza, Bravo Co. 1/5, wiping salt and sweat out of his eyes following a day-long patrol in Sangin District, Helmand province on May 4, 2011. Gilkey, who had been covering Afghanistan for NPR, was killed there in June 2016, along with his colleague, Zabihullah Tamanna, after the Afghan army unit they were traveling with was hit by a rocket grenade.

This photo by Bryan Denton was taken in Kandahar province in 2013 as part of President Obama’s troop ramp down. We see a soldier with Bravo Co. 3rd Battalion, 1st Armored Division burning sensitive military documents as the unit transitions its outpost to Afghan National Army forces. The perception at the time was that this was part of the permanent withdrawal of US combat forces from Afghanistan.

There are few pictures in this article from the second decade of the war. By October 2015, with the ground war having been largely replaced by airpower, the conflict barely registered in the US. The American accidental bombing of the Médecins Sans Frontières Trauma Center in Kunduz might have been overlooked too if photographer Andrew Quilty hadn’t been there to document the horror and “the man on the operating table.”

At least thirty staff and patients died as the result of airstrikes carried out in an hour by a US AC-130 gunship. The Afghan government claimed its forces called in the attack after coming under fire by the Taliban in the hospital compound. Quilty’s reporting disputed that and the US military subsequently took full responsibility. Quilty encountered the man on the table, the only identifiable victim, a week after the event. Four weeks later, he learned his name, Baynazar Mohammad Nazar, and told his story.

The war left behind a generation of both physically and psychologically wounded American service people. Nearly a quarter of a million US military personnel have been specifically diagnosed with Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) since 2001. The effects include headaches, seizures, motor disorders, sleep disorders, dizziness, visual disturbances, tinnitus, mood changes, memory and speech difficulties. Anecdotal evidence ties it to the dramatic spike in suicides among veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Because TBI is an “invisible wound,” a therapeutic program at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD, encouraged victims to create masks that put a face on their injuries. The program was documented by photographer Lynn Johnson for National Geographic in 2015. Marine Cpl. Chris McNair (Ret.), who was injured in Afghanistan in 2012, modeled his mask after the “muzzle” worn by Hannibal Lecter.

The war in Afghanistan generated innumerable images. And no matter how disaffecting they remain, they continue to bear all the trauma and truth of that engagement.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.