On a Friday night in January, Bill Maher made an off-kilter joke about mass shootings. By the following Monday, Tamara Holder was summoned to The Sean Hannity Show, where she has built a following playing an extreme form of devil’s advocate for Fox News. Sandwiched between two right-wing pundits and the show’s brash host, the progressive Holder held her tongue and rolled her eyes while the rest of the panel bantered. Holder may seem like an odd choice for a network that’s been called “the PR arm of the GOP.” But the Chicago-educated attorney, who has collaborated with the Rev. Jesse Jackson, is a bone fide Fox News correspondent, and she sits among an increasingly prominent group of news analysts at the conservative network–those on its left wing. Call them punching bags, foils, or the engines of honest debate, Fox’s flock of liberal commentators lay out the nation’s partisan battles in real time–on a network where coastal elites would argue that no dissenting voices exist.

Since Holder signed with Fox in 2010, the charismatic brunette has made a name for herself hashing out the kind of controversies that spring from cable’s niche airwaves into the mainstream press. Fox colleagues and guests have slammed her haircut, calling her a “Farrah Fawcett wannabe.” Once, in a discussion turned shouting match over whether Attorney General Eric Holder committed perjury, conservative radio host Bill Cunningham ordered Tamara Holder to “know your role and shut your mouth.” “My role as a woman?” Holder shot back. (The network later apologized for Cunningham’s comments.) That Monday, on Sean Hannity, while her peers picked apart Maher’s remark–he’d suggested that conservatives match a gay wedding recently staged at the Grammys “by having a mass shooting at the Country Music Awards”–Holder sat waiting for a break in the chatter. It took two interjections of “let me finish” before Holder could break in. “They finally let me speak,” she told me, a few hours after she finished taping the segment. “They had to. Otherwise they knew I would stand up and choke them.”

The ranks of liberals welcomed one more in February, when Fox hired James Carville, formerly the left flank of Crossfire and once the lead strategist for Bill Clinton. Unlike many of Fox’s liberal pundits, who’ve built their public personas playing David to a team of conservative Goliaths, Carville has been one of television’s most visible progressives for decades, often debating his wife, the conservative political consultant Mary Matalin. (The Washington Post covered his move to Fox with the headline “Pundit James Carville prepares for further torture as Fox News contributor.” ) If there were any doubts about whether Fox just looks for middling also-rans to do the left’s bidding, the arrival of Carville should resolve them.

Though MSNBC has a handful of moderate conservatives–namely Morning Joe‘s Joe Scarborough–Fox stands out for the prominence it awards its on-air naysayers, many of whom occupy regular roles on the network’s most popular shows. Personalities like Kirsten Powers, who made her way up through the Clinton administration and now goes head-to-head with Bill O’Reilly on nationalized healthcare (she’s for it), the death penalty (against), and the Iraq war (against). Their screen relationship is one of playful respect; when their debates grow heated, O’Reilly warmly calls her “Powers.”

Why would liberals in good standing risk becoming Democratic Party outcasts by going to work for Fox? And why does Fox spend good money acquiring them? The first question is easier than the second. Tamara Holder says she’s often asked how a person who once wrote for GrassRoots, a medical marijuana magazine, found herself on a network geared toward the country’s most faithful conservatives. Her one-word answer: “ratings.”

The harder question is the one directed at Fox’s motives. Ratings, of course, would be the logical answer here, too. But it’s possible that’s not the sole explanation.

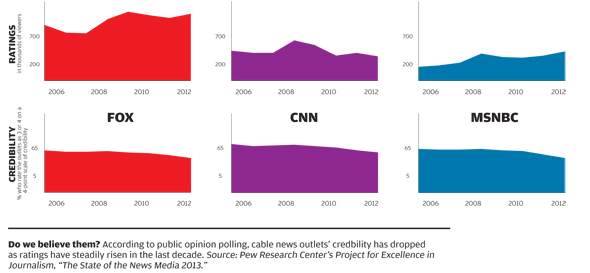

For a network that relies on a partisan base, adding a group of liberals is risky, pushing against the purity of programming that has historically been the core of Fox’s success. And yet the nation’s most-watched cable channel doesn’t maneuver without strategy. Since it launched in 1996, Fox has grown into the largest cable news network, drawing 1.1 million viewers in primetime and 1.76 million viewers in total per day, an audience that’s four times larger than its next closest competitor, CNN, and greater than both MSNBC and CNN’s audiences combined. Fox has gained this market share by its masterful manipulation of ideology, drawing an audience that’s primarily conservative, and then seeking to reinforce their values. It’s a strategy that MSNBC has scrambled to copy, setting itself up as Fox’s ideological opposite. But this year, when MSNBC’s daytime ratings slid below CNN’s, Politico’s Dylan Byers blamed the fall on MSNBC’s programming, which airs more opinion than any other news network, reaching a tipping point of “too much liberal outrage.”

Fox’s approach is more nuanced. At face value, its roster of progressives supports the network’s tagline of “Fair & Balanced,” a motto liberals have always discounted as clever branding. Whether Fox is employing adversaries because public feuds fuel ratings, or because it’s in pursuit of a franker public debate, they aren’t saying. (The network declined requests to participate in this piece.) But the way the voice of dissent is wielded–liberals are always outnumbered, thrust into subjects that descend into brawls–often undercuts balance in favor of fireworks. It’s a version of on-air political theater that some research suggests can actually further polarize opinions. Put another way, having two conservatives and a liberal can be a more powerful force than three conservatives–a counterintuitive approach that can solidify political beliefs and quash the other side.

The public’s increasing tolerance, even preference, for hard-edged, high-volume television news is a clear driver behind the dynamics of cable news. Consider the case of Crossfire. CNN killed the show in 2005 after a famous interaction where Jon Stewart blamed the show for reducing news coverage to partisan hackery by airing only extreme talking points. “You have a responsibility to the public discourse, and you fail miserably,” he said in his late-2004 appearance. Since then, Stewart has built his career on the backs of such comical partisan hackery, and when CNN re-launched Crossfire this fall, it found that, compared with the current aggression standard, the program no longer seemed extreme. “Crossfire . . . is far from a shouting match,” Laura Bennett wrote in The New Republic. “And that is precisely the problem.” The show has simply become too mild for modern tastes. What people want from cable news, says Holder, is something with a little life to it. “Anderson Cooper, I think he’s great. But he’s boring,” says Holder. “Would you watch an old guy talk rationally about a topic? Bet you’d rather watch two hot chicks who are smart and who disagree yell at each other.”

Unpacking the echo chamber

Before she ruled primetime, Megyn Kelly was a minion in Fox’s fleet of news anchors. That is, until she filmed a segment with Kirsten Powers. An outspoken liberal journalist, Powers had been brought in, along with a conservative analyst, to debate the merits of an alleged instance of voter intimidation in Philadelphia. But after introductions, the conservative analyst goes silent, leaving it to the women to battle it out. Powers, briefly, asserts that conservatives had overplayed the case. As Powers speaks, Kelly’s eyes narrow just before spitting out a response: “With all due respect, you don’t really know what you’re talking about.”

For almost seven minutes in split-screen the two go at it, their banter reaching fever pitch over which it’s impossible to make out what they’re actually arguing about. For a full minute they berate each other about whose turn it is to speak: “No, don’t talk over me.” “You’re talking over me.” Their quips grow increasingly accusational. “You’ve been completely doing the ‘scary black man thing,'” Powers whines at one point. The two focus less on the details of the case and more on whether Powers, who unlike Kelly has not read the court transcripts, is ill informed. The next morning MSNBC aired the clip, calling it “a Fox on Fox battle,” about the only analysis they could offer since the substance had been completely obscured by the force of the row. Still, the brawl is riveting: Vile makes for good television. And as it turns out, the subject–or lack thereof–was secondary to the attention the onscreen antics received. Many credit this moment with raising Kelly’s profile, vaulting her from the daytime grotto into primetime, where her show America Live became one of the highest rated on Fox News.

While MSNBC’s docket of shows contains the occasional conservative guest, they appear without the bluster and hyperbole of the typical Fox News debate–an aesthetic that MSNBC courted from its earliest days, when it aimed to resemble the amicable banter of a coffee shop. While the liberal hosts of MSNBC often skewer conservatives, the debates happen with villains who are not in the studio: lambasted, by proxy, in news clips. At Fox, they happen in person, with a real-live liberal who is often on staff. “I still think that Fox is the one place on the cable dial for sure where that kind of freewheeling debate takes place,” said Juan Williams, who was hired as one of the network’s first progressives. “Of course I find it ironic, because it’s a network with a lot of conservative personalities.” Fox has been so supportive of the liberal Williams that he has even guest-hosted The O’Reilly Factor, the network’s top-rated show. Williams attributes his good ratings to surprise: “I think the audience is like, ‘Oh, he’s there tonight. I’m used to arguing with him. How is this going to work?'” It’s hard to imagine a conservative subbing in for Rachel Maddow.

The element of surprise infuses a lot of left-right programming on Fox. In June of 2013, after the Supreme Court ruled on the Defense of Marriage Act, Sally Kohn, a community organizer and Fox contributor, tussled with Republican Congressman Tim Walberg on Geraldo at Large. For Kohn, a lesbian who lives in Brooklyn with her partner and young child, the discussion took a personal turn. After the two cycle through the usual talking points, Kohn shifts to talking about her own life, noting the federal benefits that she is denied access to, and then says to the Michigan congressman. “You’re saying that we shouldn’t [have access] because we’re somehow lesser families?”

“I’m not on TV to be famous,” said Kohn. “I’m not even on TV to make a living. The reason I go on television is the same reason I’m a community organizer–because I want to change people’s hearts and minds. As long as I’m doing this I want to talk to people where I’m going to make a difference. Preaching to the choir–what’s the point of doing that?” But Kohn’s experience with Geraldo and Walberg, where the liberal point of view got full airing, is more the exception. More often, one liberal faces off against two or even three Republicans. Williams sometimes wonders just how many conservatives they can put on against him. And the host, who sets the topic and directs the debate, is almost always conservative–all of which amounts to a home-court advantage.

Choreographing the role of those with opposing views is a technique Fox News founder Roger Ailes perfected while working as a television advisor to Richard Nixon during his 1968 presidential race. To craft an image of Nixon as a warm candidate, the campaign staged city hall debates–complete with hand-selected adversaries. “It had this veneer of authenticity because he was fielding questions from liberals, from Jews, from blacks, from different groups that might be hostile toward Nixon,” said Gabriel Sherman, author of The Loudest Voice in the Room, a biography of Ailes. “If you’re trying to appeal to an audience that doesn’t want propaganda–they want news–it’s going to make it seem like you’re giving it to them from both sides. But really it’s a situation that’s designed for conservatives to win.”

As this bit of history reminds, balance is a malleable word, and though “Fair & Balanced” has been Fox News’ motto since the channel launched, the public’s view of what constitutes “fair” coverage has shifted since then. In earlier decades, broadcast focused on relaying the news without opinion. “If you had any editorial commentary at all on a station, it ended up being very centrist,” said Jim Baughman, a media historian at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Any on-screen drama came from the facts. Balance was dramatically reshaped, however, when 60 Minutes decided to unfold the news in the form of a conversation, hiring James Kilpatrick, a Harvard-educated libertarian, to banter on stories with the liberal journalist Shana Alexander. Conversations grew heated and 60 Minutes’ ratings soared. The segments were so popular, they were satirized by Dan Aykroyd and Jane Curtin on Saturday Night Live, in jabs that seem tame by contemporary standards. (“Jane, you ignorant slut!” “Dan, you pompous ass!”)

As 60 Minutes showed, adding conflict increases the audience size for what might otherwise be a wonky program. And then came cable. Through the 1980s the number of TV news options expanded, forcing channels to get competitive to retain viewers. When CNN lifted Crossfire from the radio to cable in 1982, it solidified the fad and amplified the heat generated by such an approach. Crossfire didn’t just create a partisan battle; it explicitly announced the components of it: “On the left there is Tom Braden. On the right, Pat Buchanan. And tonight in the crossfire is our guest . . . ”

An eye for an eye

Adding opposing voices seems like a win for a democracy reliant on open debate: Even if you don’t agree, you hear the other side. But viewers pay a price for open hostility. In the mid aughts the American Political Science Review published a series of experiments showing that people trusted the authority of government less after watching arguments about politics on television. To reach their findings, the researchers played a set of political debates with and without conflict. The respondents who watched the placid exchanges didn’t change their views of government. The ones who saw a lively exchange tended to trust government less. Viewers also are more likely to retain information if it’s offered with angry disagreement–numerous studies suggest that the kinds of camera close-ups that Fox and other cable networks regularly use enhance our focus by placing us visually close to the unrest. There’s a strong evolutionary basis for our reaction: Out in the wild, strident conflict might kill us, so we pay attention. “When we assign people to watch a civil versus an uncivil program, they are increasingly likely to change the channel if they are given the civil one,” said Diana Mutz, a professor at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and author of the upcoming In Your Face Politics, chronicling several decades of research on the phenomenon.

Viewers may remember more from visceral segments, but that doesn’t mean the additional knowledge translates into more respect for the other side. Mutz’ research suggests that aggressive political debate leaves audiences even less trusting of their political foes. “The problem with that is when it comes to governing, you’re not going to feel that there’s a respectable opponent out there,” she said. “And given that sometimes they win, you’re stuck in a situation where you don’t feel like the leaders are legitimate leaders.”

This might explain why talking heads who transgress into opposing territory find themselves deluged with hate mail, in rates that rise along with the hostility of a particular segment. After filming with the anti-abortion activist Michelle Malkin, Tamara Holder received hundreds of outraged comments, some laced with personal threats. “Someone said I should have all my arms and legs removed by all the dead babies I killed,” she said. The furor was so extreme that the two no longer appear on television together. “The segments somehow got ratings, and that’s great, but it wasn’t facts–it’s just this weird screaming match,” Holder said. This aggression loop hits all parties, as the conservative pundit Erik Erickson demonstrated, in a post on his blog, RedState, after announcing a move from CNN to Fox. “For three years I have received unmitigated hate and loathing from the left and, ironically, from a lot of folks on the right,” he wrote. “For some reason, saying something negative about the GOP was fine here at RedState, but saying the same damn thing on CNN brought in a flurry of emails from conservatives accusing me of selling out. Funny how that works.”

Last October, liberal Fox contributor Sally Kohn stood before a packed auditorium and attacked the issue head on. “So when I do my job, people hate me,” she began her TED Talk. (“At this point, my only request with the word ‘dyke’ is that you spell it correctly,” she joked.) In the six-minute speech, Kohn called on liberals and conservatives to transcend party lines with more respect. It’s not enough, she argues, to simply show up and recite a series of informed talking points. Reaching viewers requires listening to, understanding, and empathizing with, the other side–even when the other side consists of people who “don’t want me or people like me to even exist.” Kohn labeled the idea with a catchy term: emotional correctness. “What I’ve realized is that political persuasion doesn’t begin with ideas or facts or data–political persuasion begins with being emotionally correct.”

A few weeks after she delivered the talk, Kohn announced she was leaving Fox. (She describes the parting as “amicable” and signed with CNN last January.) Even though her foes now appear with less fervor and in smaller number, she still feels the need to empathize with them. Her philosophy of debate stands, regardless of who is listening. “It’s easy enough to go on television and think, It’s about me, I’m debating,” she said. “I guess I feel that I’m at my best when I’m thinking about the people who are watching and what they’re getting out of this.” Perhaps the structure of debate matters less than how we play the game.

Alexis Sobel Fitts is a senior writer at CJR. Follow her on Twitter at @fittsofalexis.