Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

Mike Hudson began reporting on the subprime mortgage business in the early 1990s when it was still a marginal, if ethically challenged, business. From his street-level perspective, he could see the abuses and asymmetries of the market in a way that the conventional business press could not. But because it appeared mostly in small publications, his reporting was largely ignored. Hudson pursued the story nationally, via a muckraking book, Merchants of Misery; in a 10,000-word exposé on Citigroup-as-subprime-factory, which won a Polk Award in 2004 for the magazine Southern Exposure; and in a series on the subprime leader, Ameriquest, for the Los Angeles Times in 2005. He continued to pursue the subject as it metastasized into the trillion-dollar center of the Financial Crisis of 2008—briefly at The Wall Street Journal and now at the Center for Public Integrity. In 2010 he published The Monster: How a Gang of Predatory Lenders and Wall Street Bankers Fleeced America—and Spawned a Global Crisis. Hudson, 50, is the son of an ex-Marine who also was a legendary local basketball coach. He started out on rural weeklies, covering championship tomatoes and large fish, even producing a cooking column. But as a reporter for The Roanoke Times, he turned to muckraking and never looked back. CJR’s Dean Starkman interviewed Hudson in the spring of 2011. A longer version of their conversation is at cjr.org/feature/hudson.php.

Follow the ex-employees

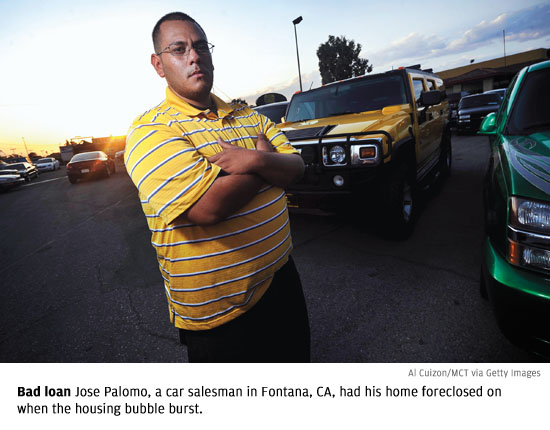

I was doing a series on poverty in Roanoke, and one of the local legal aid attorneys said, “It’s not just the lack of money—it’s also what happens when they try to get out of poverty.” He said there are three ways out: They bought a house, so they got some equity; they bought a car, so they could get some mobility; or they went back to school to get a better job. And he had example after example of folks who, because they were doing that, had gotten deeper in poverty, trapped in unbelievable debt.

His clients often dealt with for-profit trade schools—truck-driving schools that would close down, medical-assistant schools that no one hired from. And they’d end up three, four, five, eight thousand dollars in debt, unable to repay it, and then of course be prevented from ever again going back to school because they couldn’t get another student loan. So that got me thinking about what I came to know as the poverty industry.

I applied for an Alicia Patterson Fellowship and proposed doing stories on check-cashing outlets, pawn shops, second-mortgage lenders (they didn’t call themselves “subprime” in those days). This was ’91. I came across a wire story about something called the Boston “second-mortgage scandal,” and got somebody to send me a thick stack of clips. It was really impressive. The Boston Globe and other news organizations were taking on the lenders and the mortgage brokers, and the closing attorneys, and on and on.

I was trying to make the story not just local but national. I had some local cases involving Associates [First Capital Corp., then a unit of Ford Motor Company]. Basically, it turned out that Ford, the old-line carmaker, was the biggest subprime lender in the country. The evidence was pretty clear that they were doing many of the same kinds of bait-and-switch salesmanship and, in some cases, pure fraud, that we later saw take over the mortgage market. I felt like this was a big story; this is the one! Later, investigations and congressional hearings corroborated what I was finding in ’94, ’95, and ’96. And it seems so self-evident now, but I learned that ex-employees often give you a window into what’s really going on with a company. The problem has always been finding them and getting them to talk.

Subprime goes mainstream

In the fall of 2002, the Federal Trade Commission announced a big settlement with Citigroup, which had bought Associates, and at first I saw it as a positive development, like they had nailed the big, bad actor. I’m doing a 1,000-word freelance thing, but as I started to report I heard from people who were saying that this settlement is basically giving Citigroup absolution, and allowing them to move forward with what was, by Citi standards, a pretty modest settlement. And the other thing that struck me was the media were treating this as though Citigroup was cleaning up this legacy problem, when Citi itself had its own problems. There had been a big New York magazine story about [Citigroup Chief Sanford I.] “Sandy” Weill. It was like “Sandy’s Comeback.” I saw this and said, “Whoa, this is an example of the mainstreaming of subprime.”

I pitched a story about how these settlements weren’t what they seemed, and got turned down a lot of places. Eventually I called the editor of Southern Exposure, Gary Ashwill, and he said, “That’s a great story; we’ll put it on the cover.”

I interviewed 150 people, mostly borrowers, attorneys, experts, industry people—but the stuff that really moved the story were the former employees.

As a result of the Citigroup stuff, I got a call from a filmmaker [James Scurlock] who was working on what eventually became Maxed Out, about credit cards and student loans and all that kind of stuff. And he asked if I could go visit, and in some cases revisit, some of the people I had interviewed and he would follow me with a camera. So I did sessions in rural Mississippi, Brooklyn and Queens, and Pittsburgh. Again and again you would hear people talk about these bad loans they got. But also about stress. I remember a guy in Brooklyn, not too far from where I live now, who paused and said something along the lines of: “You know I’m not proud of this, but I have to say I really considered killing myself.” Again and again people talked about how bad they felt about having gotten into these situations. They didn’t understand, in many cases, that they’d been taken in by very skillful salesmen who manipulated them into taking out loans that were bad for them.

If one person tells you that story, you think maybe it’s true, but you don’t know. But you’ve got a woman in San Francisco saying, “I was lied to and here’s how they lied to me,” and a loan officer for the same company in suburban Kansas saying, “This is what we did to people.” And then you have another loan officer in Florida and another borrower in another state. You start to see the pattern.

I was not talking to analysts. I was not talking to high-level corporate executives. I was not talking to experts. I was talking to the lowest-level people in the industry—loan officers, branch managers. I was talking to borrowers. And I was doing it across the country and doing it in large numbers. And when you actually did the shoe-leather reporting, you came up with a very different picture than the PR spin you were getting at the high level.

One day, Rich Lord [who recently published the muckraking book, American Nightmare: Predatory Lending and the Foreclosure of the American Dream] and I were sitting in his study. Rich had written a lot about Household International [parent of Household Finance], and I had written a lot about Citigroup. Household had been number one in subprime, and now CitiFinancial/Citigroup was number one. This was in the fall of 2004. We wondered, who’s next? Rich suggested Ameriquest.

I started looking up Ameriquest cases, and found lots of borrower suits and ex-employee suits. There was one in particular, which basically said that the guy had been fired because he had complained that Ameriquest’s business ethics were terrible. I found the guy in the Kansas City phone book, and he told me a really compelling story. One of the things that really stuck out is, he said to me, “Have you ever seen the movie Boiler Room [the 2000 film about an unethical pump-and-dump brokerage firm]?”

By the time I had roughly 10 former employees, most of them willing to be on the record, I thought: This is a really important story. Ameriquest at that point was on its way to being the largest subprime lender. So I started trying to pitch it.

The Los Angeles Times liked the story and teamed me with Scott Reckard, and we worked through much of the fall of 2004 and early 2005. We had 30 or so former employees, almost all of them basically saying that they had seen illegal practices, some of whom acknowledged that they’d done it themselves: bait-and-switch salesmanship, inflating people’s incomes on loan applications, inflating appraisals. Or they were cutting and pasting W2s or faking a tax return. It was called the “art department”—blatant forgery, doctoring the documents. In a sense I feel like I helped them become whistleblowers because they had no idea what to do. One of the best details was that many people said they showed Boiler Room—as a training tape! And the other important thing about the story was that Ameriquest was being held up by politicians, and even by the media, as the gold standard—the company cleaning up the industry, reversing age-old bad practices in this market. To me, theirs was partly a story of the triumph of public relations.

Leaving Roanoke

I resigned from the Roanoke Times and for most of 2005 was freelancing full-time. I made virtually no money that year, but by working on the Ameriquest story, it helped me move to the next thing. I was hired by The Wall Street Journal to cover the bond market. Of course, I came in pitching mortgage-backed securities as a great story. I could have said it with more urgency in the proposal, but I didn’t want to come off as an advocate.

Daily bond-market coverage is their bread and butter, and I tried to do the best I could on it. I was doing what I could for the team but I was not playing in a position where my talents and my skills were being used to the highest. I felt like I had a lot of information that needed to be told, and an understanding that many other reporters didn’t have. And I could see a lot of the writing focused on deadbeat borrowers lying about their income, rather than how things were really happening.

Through my reporting I knew two things: that there were a lot of predatory and fraudulent practices throughout the subprime industry. It wasn’t isolated pockets, rogue lenders, or rogue employees. It was endemic. And I also knew that Wall Street played a big role in this, and that Wall Street was driving or condoning and/or profiting from a lot of these practices. I understood that, basically, the subprime lenders, like Ameriquest, and even Countrywide, were creatures of Wall Street. Wall Street loaned these companies money; the companies then made loans and off-loaded the loans to Wall Street; Wall Street then sold the loans as securities to investors. It was this magic circle of cash flowing. The one thing I didn’t understand was all the fancy financial alchemy—the derivatives, the swaps—that was added on to put the loans on steroids.

It’s clear that people inside a company could commit fraud and get away with it, despite a company’s best efforts. But I don’t think it can happen in a widespread way when a company has basic compliance systems in place. The best way to connect the dots from the sleazy practices on the ground to people at high levels was to say, “Okay, they had these compliance people in place. Did they do their jobs? And if they did, what happened to them?”

In late 2010, at the Center for Public Integrity, I got a tip about a whistleblower case involving someone who worked at a high level at Countrywide. This is Eileen Foster, who had been an executive vice president, the top fraud investigator. She was claiming before OSHA that she was fired for reporting widespread fraud, but also for trying to protect other whistleblowers within the company who were reporting fraud at the branch and regional levels. The interesting thing is that no one in the government had ever contacted her! In September 2011, this became, “Countrywide Protected Fraudsters by Silencing Whistleblowers, say Former Employees,” one of CPJ’s best-read stories of the year; 60 Minutes followed with its own interview of Foster, in a segment called, “Prosecuting Wall Street.” It was very exciting.

There needs to be more investigative reporting of problems that are going on now, rather than post-mortems about financial disasters or crashes or bankruptcies that have already happened. And that’s hard to do. It takes a real commitment from a news organization, because you’re working on these stories for a long time, and market players you’re writing about do some real pushback. But there needs to be more of this early-warning journalism.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.