Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

It wasn’t the biggest story I broke in Miami. But it left its mark. In the fall of 1998, I was the first reporter to write about a federal investigation targeting Atlanta Falcons wide receiver Tony Martin. The DEA was looking into him on allegations of laundering the money of a convicted Miami drug trafficker and neighborhood pal. I was a few months into a new job at the Miami New Times, the Magic City’s alt-weekly, and wrote the story after a source tipped me off. I confirmed the investigation with the feds, lawyers, and folks on the street months before Martin was formally indicted—and then, ultimately, acquitted.

About a week after the story came out, a sportswriter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution called me up. Congrats, good stuff, would love to do a follow-up. Any chance you can share your sourcing? I shared what I could, looking forward to the New Times getting a little recognition. Except we didn’t. He called back a few days later and said his editor didn’t want to cite us—we weren’t a reputable enough publication. That was some shocking honesty. Appreciated, I guess. When the Journal’s story came out, the wires picked it up. Guess who got the credit then?

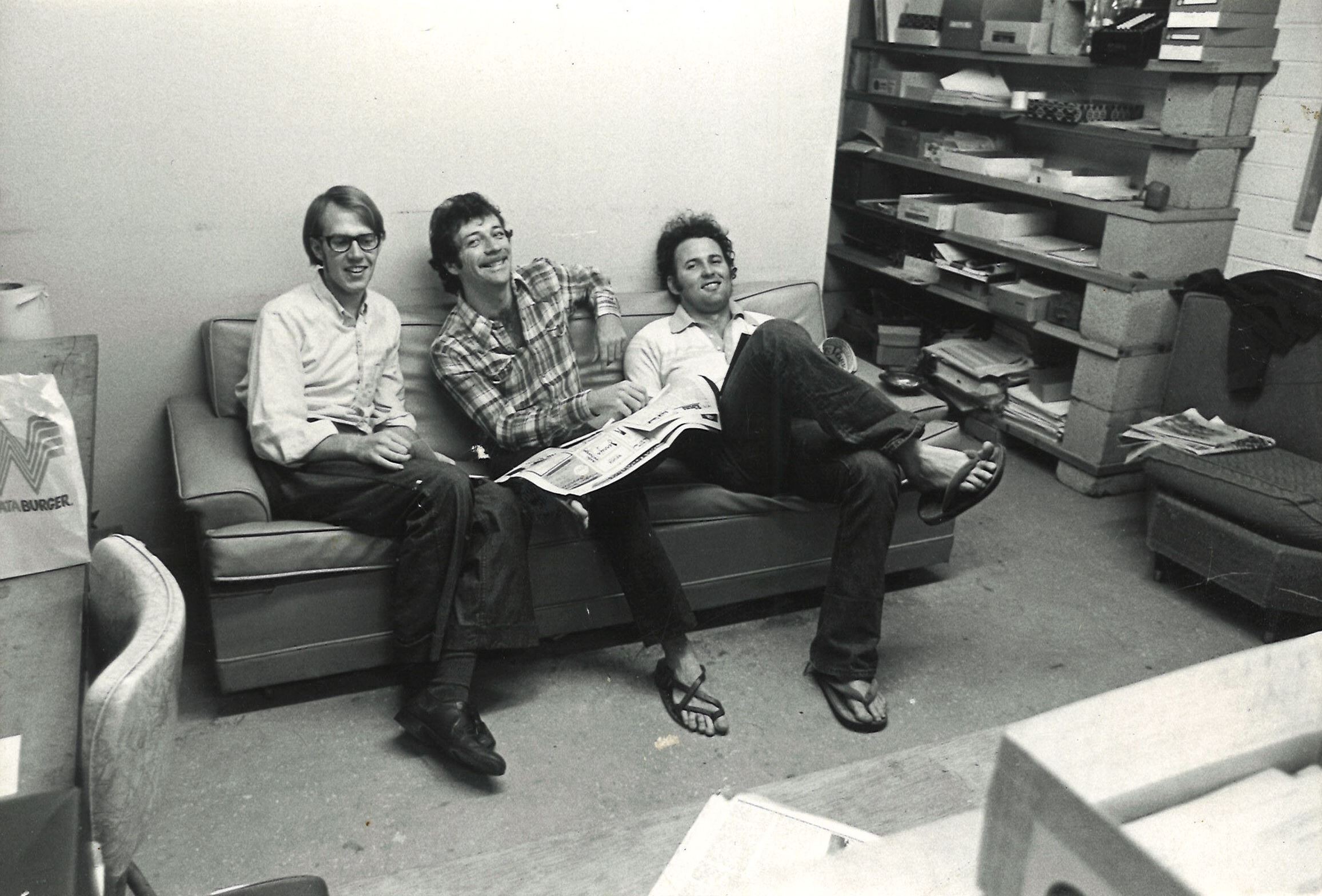

I was reminded of this mild indignity recently while listening to Hold Fast, the exquisitely told nine-episode podcast from Audible about the founders of the New Times Media chain of alt-weeklies and the federal case against them on charges of facilitating prostitution through their Backpage advertising website. The podcast, produced by three former Miami New Times journalists—Trevor Aaronson, Sam Eifling, and Michael Mooney—is a court drama and an exploration of freedom of speech, but it’s also a history of the world of alt-weeklies. (Aaronson and Eifling are friends, but I’m writing this anyway—how very alt-weekly of me.) The podcast, along with a new oral history of the Village Voice, The Freaks Came Out to Write, by Tricia Romano, chronicles the rise and fall of the alt-weekly universe and pays tribute to the genre-busting journalism that transformed criticism, writing, and newsgathering across the country but that never seems to get its due in the mainstream narrative.

As if to prove my point, just look at the lack of coverage surrounding the fate of New Times Media founders Mike Lacey and Jim Larkin. It’s hard to think of two more significant contemporary press figures. Lacey and Larkin reshaped American journalism at the local level. They did this by buying up alternative weeklies until they had the largest chain of such papers in the history of the country, and then recruited professionals and demanded they produce great stories.

Major American cities—Los Angeles, Miami, Houston, Phoenix, and ultimately New York—hosted New Times papers, all notable for their vivid cultural criticism and aggressive investigative reporting. Their local coverage often made national news. The Fort Lauderdale paper revealed that airport officials had detained 9/11 hijacker Mohamed Atta when he first entered the country, but released him because of a mandate to be more customer-friendly. The Phoenix paper found evidence that Motel 6 employees in Washington State were ratting out migrants to the immigration authorities. The Miami paper reported on Biogenesis, the anti-aging clinic accused of flooding Major League Baseball with steroids. New Times papers won all the major awards, including the Pulitzer, the George Polk, and the Livingston.

We were given the freedom and the support to get the most powerful stories we could in our communities. I traveled to out-of-state prisons to expose a ring of drug-dealing cops. I went to Haiti to cover the fall of Aristide (well, I had to go AWOL to do it, but they took me back). I once expensed a night in an inner-city cocaine speakeasy. I never had so much fun pulling a regular paycheck. As the Hold Fast podcasters duly note, these were not family papers.

I don’t want to imply that it was only New Times weeklies bringing home the big stories. Willamette Week in Oregon won a Pulitzer for revealing a former governor’s relationship with an underage babysitter and the efforts to cover it up. The Voice, the doyen of the weekly world, took home three Pulitzers, one for international reporting about AIDS in Africa. The daily papers tried to ignore us until they couldn’t.

It wasn’t just our stories that had an impact over the years, it was our entire approach. We shed the false objectivity the dailies had labored under since the 1950s. My editor, Jim Mullin, oriented me early on: “We have to be fair. We don’t have to be objective.” The alts were the first media to acknowledge that not everybody was straight. We ran stories about the LGBTQ communities and published their personal ads seeking connections long before newspapers would ever use the word “gay.” We made newswriting less formal. We took enormous risks both stylistically and journalistically. As a result, we sometimes failed with flair; there were plenty of boring, long-winded stories. But we had the freedom to fail. These days, you see much more of the frank tone that characterized alt-weeklies in mainstream American journalism, like when an outlet describes a politician’s lies as lies—and it’s more fun as a result.

Lacey and Larkin were instrumental in making all this possible. The two held fast on many press freedom issues over the past five decades. As the podcast notes, their flagship paper, the Phoenix New Times, born out of the anti-war movement in the 1970s, was later criminally charged in Arizona for running ads from abortion clinics when that was still illegal in the state pre–Roe v. Wade. In 2007, Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio threw both men in jail for publishing a grand jury investigation. (The charges were quickly dismissed.) They weren’t cowed: their papers went after Arpaio again and again, alleging unconstitutional treatment and abuse of prisoners and immigrants.

But for all the good they did to freshen up the media landscape, Lacey and Larkin had significant faults. They were arrogant about their approach to news and could be bullies. After years of competing with the Village Voice’s chain of weeklies, New Times Media finally took over their rivals in a 2005 “merger” in which they had a controlling interest. Lacey and Larkin were determined to remake the storied paper in their image, and in the process they alienated staff, ran through editors, and finally sold the Voice. “I hate those assholes who ruined it,” veteran Voice writer James Ridgeway succinctly told Romano.

This was already the era’s denouement. Small ads, especially classifieds, were the mainstay of the alt-weekly economy. When Craigslist’s free classifieds rolled onto the scene, in the late nineties and early aughts, like a boulder tumbling downhill, it crushed the papers. To compete, Lacey and Larkin started their own Craigslist, called Backpage. It was quickly overrun by ads for sex workers. Critics began accusing the papers of facilitating prostitution—and worse.

To buffer their papers from criticism and boycotts, Lacey and Larkin spun Backpage off into an independent business. As a standalone entity, this made it a nice fat target in the eyes of the public and the feds in Arizona. For the complexities of the case, what was and wasn’t protected speech, and how the internet publishing laws changed, you’ll have to listen to the podcast. But urged on by politicians who had been skewered by New Times papers in the past (like John McCain), prosecutors went after Lacey and Larkin and other Backpage executives for running a business that was aiding prostitution and laundering money. After a 2021 mistrial, the feds went at them again, winning a conviction against Lacey in 2023 on one count of money laundering. In a fit of prosecutorial zeal, the feds announced in January that they would try him again on several charges the jury deadlocked on. Larkin took his own life right before the trial. There was no mention of his death in the New York Times or the Washington Post.

Today, what was New Times Media is Voice Media Group, a mere five papers and a digital advertising agency, from more than triple that number back in the day. The staffs are a shadow of what they were, yet they manage the occasional knockout story. I can only wonder: For how long? Clearly the glory days are past. But like their founders, maybe the papers themselves were always destined to flame out.

Fittingly, my own tenure at Miami New Times also ended in flames, of a sort. I clashed mightily with two editors after I learned of a blog they ran that belittled staffers. I “confronted the editors about their nasty online messages,” as Miami’s Daily Business Review reported, and they complained about me. Lacey suspended all three of us without pay, and I left for another publication. Right before walking out the door, though, I sent that pugnacious Irishman a note saying no hard feelings, I had a great time. And I meant it.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.