Before leaving Pulitzer Hall, the Columbia Journalism School building in Manhattan, on Election Night, I stopped by our makeshift newsroom to absorb some of the evening’s excitement. It was still early in the process; polls were just beginning to close around the country. Students were gathering and checking in with their professors, who were their editors for the night. There was a sense of history in the making.

My mind went back 44 years, to November 7, 1972, when I was a student at the school. I was just 23 years old, but on that night, I got to cover a presidential election and write about it for a special edition of the Columbia News. We followed the results on an AP teletype machine that spewed out state totals and on a black-and-white TV featuring Walter Cronkite on the screen.

The school was much smaller back then (after all, this was before Watergate made our profession sexy). There were 123 students in my class, roughly half our class size today. But the division of labor for election night wasn’t all that different. Some students, their pockets full of dimes, got to go to the campaign headquarters and phone in scene and color (from pay phones, of course), while others, like me, were on the rewrite bank. I typed my story on an IBM Selectric.

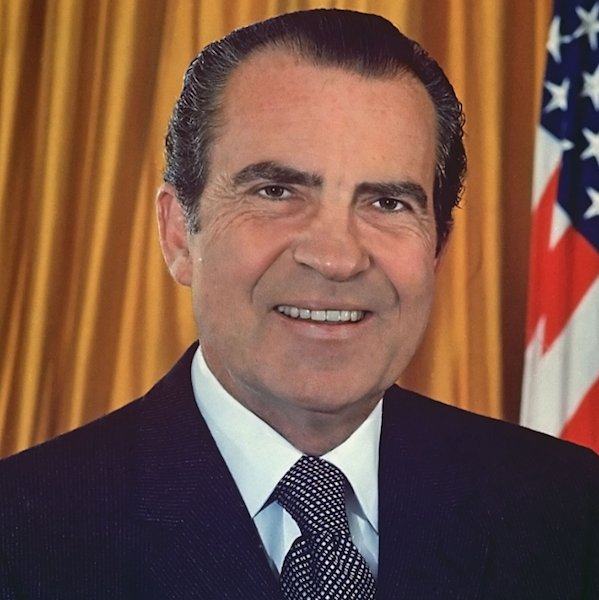

It was not a late night. President Richard Nixon, running for re-election, trounced Senator George McGovern of South Dakota, winning 49 states. McGovern won Massachusetts and the District of Columbia. Nixon even beat McGovern in his home state of South Dakota.

By contrast, the night of November 8, 2016 was a long one. It was after 3 am when Donald J. Trump took the stage and claimed victory. A huge, unanticipated upheaval had taken place in America, and few of us in New York media circles had seen it coming. At a Columbia Journalism School forum the next day, students were visibly upset and many, especially women and people of color, spoke about their fears. They worried aloud about Trump’s incendiary comments during the campaign about women, Muslims, African Americans, and the press. After all, here was a candidate for president who said he planned to “open up” the nation’s libel laws so “we can sue them and win money.”

I took the microphone and reminded the students that, like Trump, Richard Nixon, the president of my youth, was an ardent foe of press freedom. He wiretapped journalists’ phones, unleashed the Internal Revenue Service on them, and featured them prominently on his “enemies list.” In one landmark case, he went to federal court to stop The New York Times from publishing the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of American involvement in Vietnam. (Nixon lost when the Supreme Court reversed a lower court injunction and allowed the Times to keep publishing.) “Nixon won by a landslide that night,” I told the students, “but most important, he never served out his term. He was forced to resign less than two years later because of two young and smart reporters on The Washington Post.”

As George Packer reminds us in this week’s New Yorker, Nixon was felled by more than Woodward and Bernstein. It was the courts, the Congress and, as we later learned, the FBI, whose deputy director, Mark Felt, turned out to be Deep Throat.

But this was no time for a full history lesson. My purpose was to highlight the role of the press in bringing Nixon down and draw a line from Nixon to Trump. “We’ve been through worse,” I added.

Nixon-Trump comparisons are not new. In fact, Trump himself made one on the eve of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland in July. “I think what Nixon understood is that when the world is falling apart, people want a strong leader whose highest priority is protecting America first,” Mr. Trump said, according to The Times. “The ’60s were bad, really bad. And it’s really bad now. Americans feel like it’s chaos again.”

The Times reported that quote in a “news analysis” by Michael Barbaro and Alexander Burns headlined “It’s Donald Trump’s Convention. But the Inspiration? Nixon.”

“In an evening of severe speeches evoking the tone and themes of Nixon’s successful 1968 campaign,” they wrote, “Mr. Trump’s allies and aides proudly portrayed him as the heir to the disgraced former president’s law-and-order message, his mastery of political self-reinvention and his rebukes of overreaching liberal government. It was a remarkable embrace–open and unhesitating–of Nixon’s polarizing campaign tactics, and of his overt appeals to Americans frightened by a chaotic stew of war, mass protests and racial unrest.”

There was no mention in that article that Trump was also using Nixon’s playbook in his treatment of the press, especially what he saw as the elite East Coast liberal media. Like Trump and his Twitter account, Nixon found his own way around the establishment press by taking his case directly to the people through the new medium of television. Television turned out to be both his friend and his undoing.

In 1952, when Nixon was the vice presidential nominee running with Dwight Eisenhower, his place on the ticket was in jeopardy because of a report in the New York Post that he had access to “a secret rich men’s trust fund” that enabled him to live lavishly. Nixon delivered a half-hour televised address in which he defended himself and said that regardless of the charges against him, he was going to keep one gift: a black-and-white dog who had been named Checkers by the Nixon children. It became known as the “Checkers speech.”

In 1960, however, TV was not so kind to him when, running for president against John F. Kennedy, he appeared tired, sweaty and nervous on the screen during a presidential debate. It has often been said that people who heard the debate on radio thought Nixon won; those who saw it on TV thought Kennedy won. Nixon did not have a face for TV.

TV was also his undoing because his fall was played out for all to see when the Senate Watergate hearings were broadcast gavel-to-gavel on PBS and witnesses like John Dean, the former White House Counsel, boldly testified that the president knew of the cover-up.

Trump too is a creature of TV. He has exploited it brilliantly, from his game show, The Apprentice, which ran in various formats across 14 seasons on NBC, to hosting Saturday Night Live, to making the rounds of the late-night talk shows. Although he has blundered during the campaign, in the debates and in interviews, TV remains his friend. Twitter is his constant companion.

Trump also shares Nixon’s antipathy for the press. Some of Nixon’s most enduring quotes are about the media. In 1962, when Nixon lost in his bid to become governor of California, he bitterly lashed out at the media, saying “now that all the members of the press are so delighted that I have lost, I’d like to make a statement of my own. Just think how much you’re going to be missing.”

He later added: “You don’t have Nixon to kick around anymore because, gentlemen, this is my last press conference.”

It wasn’t, of course. In one of the great political comebacks of all time, Nixon defeated a host of challengers–including Governor Ronald Reagan of California and Governor Nelson Rockefeller of New York–to secure the Republican nomination for president. He went on to beat Vice President Hubert Humphrey in the general election to become the 37th president of the United States.

He started his presidency with this axiom: “The press is the enemy.” That was what he frequently told the White House staff, according to Mark Feldstein’s “Poisoning The Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington’s Scandal Culture.” At first, Nixon gave the main attack role to his vice president, Spiro Agnew, who labeled the press “a small, unelected elite,” and famous called them “nattering nabobs of negativism,” a phrase penned by William Safire, then a White House speechwriter.

Agnew was forced to resign in 1973 after being charged with accepting more than $100,000 in bribes while holding elected office in Maryland. He surrendered his role as vice president roughly a year before Nixon, facing impeachment, would himself be forced to resign.

There were others in the White House who picked up Nixon’s anti-press mandate, including G. Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt, who plotted to assassinate one of Nixon’s major irritants, the syndicated columnist Jack Anderson, a tale told in detail in the Feldstein book. The plot was never carried out, but the two would later plan another White House caper: the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington on June 17, 1972, a scandal investigated by two Washington Post reporters, Bob Woodward, 28, and Carl Bernstein, 29.

My students especially like to hear the story of these two reporters. When I invoked their work at the J School forum, several students thanked me for injecting a note of hope at a dismal time.

“You have your work cut out for you,” I told them. “The goal is not to fear Trump, but for Trump to fear you.”

Ari L. Goldman is a professor of journalism at Columbia and the author of four books, including The Search for God at Harvard and Being Jewish.