Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

For a moment in time when the internet was new, and even a little later when excitement about longform reached a fever pitch, one important question was largely ignored: Who is this particular story for, and how can I make sure that an audience sees it?

It’s a question journalists are only beginning to answer.

A year or so ago, three of us at The Big Roundtable asked ourselves, how do we—with limited access to Web analytics—better understand the reading behavior of longform lovers, and what it is that compels those readers to share a story? Were there a few basic lessons, we wanted to know, that every publication could easily, and with no technical overhead, adopt—a few universal truths of sharing?

So we conducted a study, funded by Columbia University’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, that looked at how 63 self-identified longform readers found, read, and shared long stories over the course of 21 days. The participants included 33 men and 30 women who ranged in age from approximately 20 to 50 years old, though slightly more than half were 32 and younger. Most came to us through Narratively and Medium, both of which included a call for participants in their newsletters; others got in touch after learning about the experiment in The Big Roundtable’s newsletter.

Among our most remarkable findings is that readers finished 94% of the longform pieces they started. To understand why that completion rate is a big deal, we have to step back in time to the early days of the internet, when conventional wisdom held that readers would not be interested in stories longer than the height of a computer screen.

Instead, with much faster download speeds and the advent of the tablet’s “lean back” reading experience, journalism has seen a rise in “longform” ventures, among them curated sites like Longreads.com and Longform.org, and publishers of original content like the Atavist, Narratively, and The Big Roundtable. In addition, more and more media organizations, like BuzzFeed and Politico, have begun publishing longer pieces, while others, such as The New York Times, have thrown their resources and manpower behind ambitious design projects like “Snow Fall.”

“Snow Fall” was a milestone achievement in online interactive storytelling, and quickly every newspaper and Web magazine seemed to want its own version. In the flurry of excitement about the story’s great design, the question of who was reading it got lost.

Where once the only measure of success for a magazine story was the number of copies sold, which gave little indication of which articles were most widely read, digital publishing offers a host of metrics designed to measure an individual story’s “success.”

But analytics offer an incomplete picture of reader behavior, and little real insight into how readers engage. Page views, entrances, time on page, and bounce rates are helpful to only a limited degree. In place of empirical evidence, user comments, social media chatter, and emailed feedback give journalists a glimpse of the people engaging with their piece (whether for good or ill); but on a whole, journalism’s picture of The Reader is still hazy.

Steve Jobs famously said, “Customers don’t know what they want.” The same can be said for readers. So we figured: Let’s stop asking readers what they want and start asking them who they are, and how they act when they encounter longform stories.

Our participants read a total of 1,349 stories in three weeks and shared 469 (35%) of them. Intuition tells us that a 35% is a high sharing rate, so it’s important to keep in mind that our participants are longform lovers who may be predisposed to finding, reading, and sharing longer stories at a higher frequency that the average reader coming across a magazine piece.

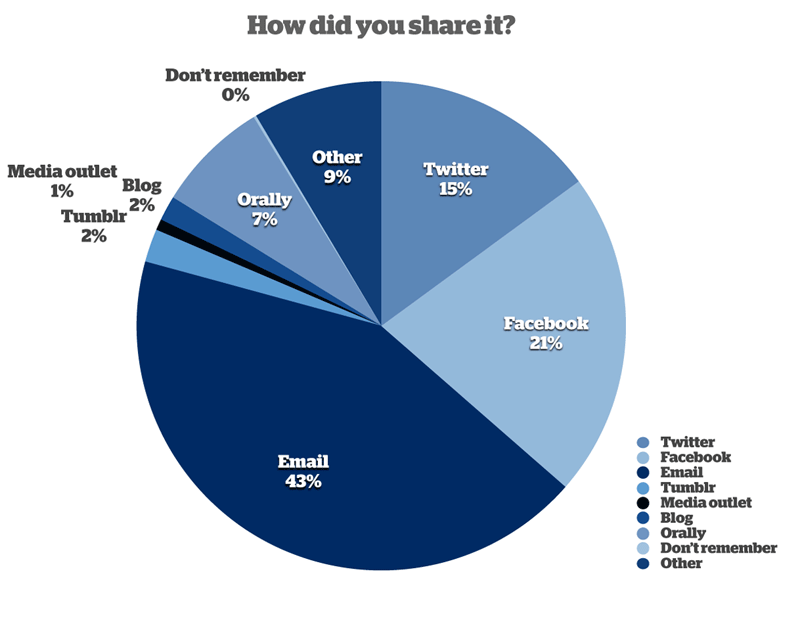

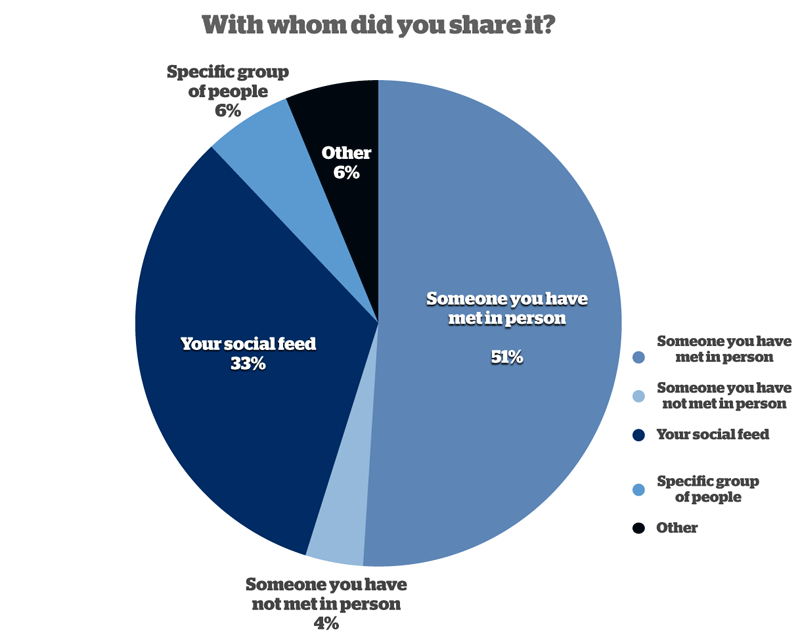

The 469 stories were shared a total of 549 different times, most commonly through email (43%), Facebook (21%), and Twitter (15%). People shared the story 51% of the time with someone they had met in person, 33% of the time with their social feed, 6% with a specific group of people, such as members of a writers’ group, and 4% with someone they had not met in person.

At The Big Roundtable, we had been publishing virtually all our 40 plus stories on Thursdays and Fridays, in the belief that weekends were a time for reading long stories. But that wasn’t quite right. According to our findings, participants read 50% of the stories during the week and 50% over the weekend.

Although people were likely to read the same amount over the two days of the weekend as they were during the five days of the week, they were much less likely to share a story they read over the weekend. Only 18% of stories read over the weekend were shared, compared with 52% of stories read during the week.

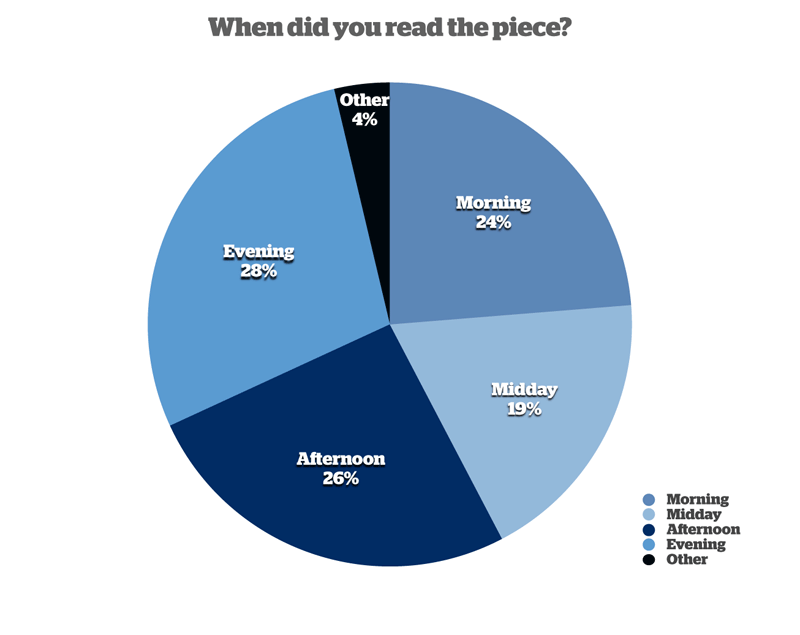

The time of day participants chose to read was fairly evenly distributed between evening (28%), afternoon (26%) and morning (24%). Nineteen percent of participants reported reading midday. Readers finished a long story in one sitting 66% of the time; 28% of the time, they finished after putting the piece down and returning to it later.

When readers do decide to share a story, the most powerful tool—email—is also limited: Personal emails from one individual to the next are most powerful at getting someone to act, but because the interaction is between so few people, it’s less likely that the recipient will be someone with the power to make a story go viral.

Email brings with it a social compact: that the sender knows the recipient and, it seems reasonable to conclude, understands what might interest the recipient most. It also feels fair to conclude that in the act of sharing via email, the sender assumes a certain risk, one built upon the assumption of knowledge and understanding of the recipient’s interests. After all, in sharing a long story, the sender is essentially saying to the recipient, “I know you well enough not just to believe, but to know that you will want to commit half an hour or so to this story.” If a story recommendation misses the mark, it dilutes the sharer’s future power. Far safer, then, is sharing via social media, especially Facebook and Twitter, where the broadcasted story is essentially scattered to all of one’s “friends,” regardless of whether they are people the sender has met.

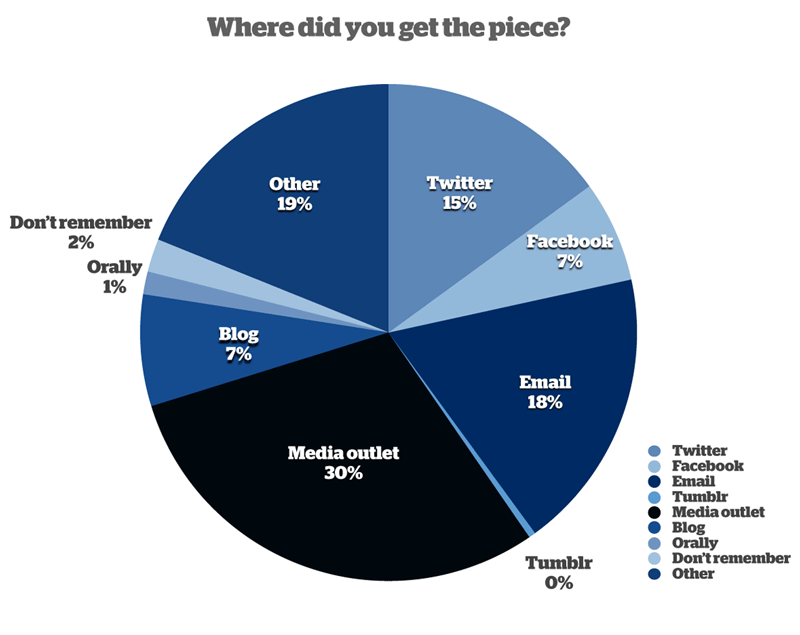

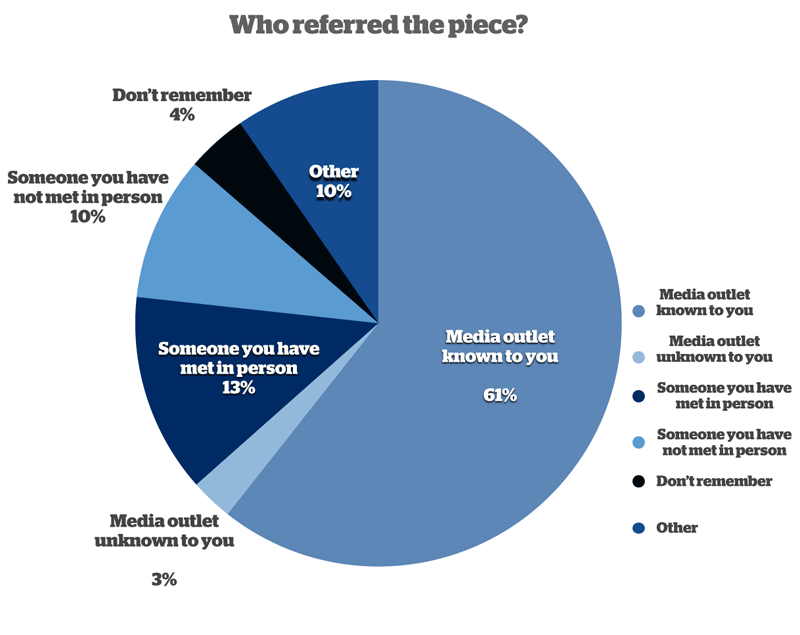

Our respondents got stories from a media outlet’s website 30% of the time. The next most common sources were “other” (19%) and email (18%), followed by Twitter (15%). The most common answer choices for “other” were: magazine/print subscription, magazine/newspaper app, curatorial services, and search engine.

It appears that a trusted name brings with it the warrant of quality; readers are more likely to invest their time in a story that comes from a media outlet they know rather than one they don’t. This, in turn, suggests that curation is an essential component of how longform gets read—whether that curator is an editor at a media outlet the reader values, or a friend.

Publishers are beginning to see the fuzzy outlines of their readers, to better understand who they are and what stories they tend to click on, but anecdotal evidence and intuition continue dictate how these organizations share stories.

So why do some stories take off while others—of equal quality and intrigue—don’t?

The answer here, too, is linked to the notion of trust, in this case the trustworthiness of the source who first shared the story. The very nature of the work, and the processes through which longform stories are discovered, consumed, and shared are antithetical to the scattershot clickbait method of grabbing eyeballs that dominates so much traffic on the Web.

Anecdotally we understand that long reads are never going to compete with the likes of “Charlie Bit My Finger” (800 million page views) or BuzzFeed’s listicles, and to use those measures of viral success as a yardstick would be inappropriate.

Long reads take time to produce—to report, write and edit—and time to read, and they demand something of a reader, with the promise of delivering something more lasting in return.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.