Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In a contract bargaining meeting on Wednesday, October 12, Gannett, which had just made what senior reporter Diane Smith characterized on Twitter as an “insulting, lowball financial proposal” to the Record-Courier NewsGuild in Kent, Ohio, ominously suggested union members tune in to the monthly town hall meeting that afternoon. In a widely unexpected move, Gannett president and CEO Mike Reed announced several company-wide cuts—just two months after laying off four hundred employees and eliminating four hundred open positions in response to a dismal second quarter with $54 million in losses.

“I’ve been with this company for [nine years], and all I’ve known is cuts,” Adrian Szkolar told the Tow Center, “but even this newest round of cuts took everyone by surprise. It came out of nowhere for me.” Szkolar, a producer for USA Today, Gannett’s flagship national brand, and member of the Atlantic DOT Guild, said he’s used to annual or sometimes biannual cuts, but never cuts just a couple of months apart.

The October cuts, which Reed attributed to the “deteriorating macroeconomic environment” in a staff-wide email, include a 401(k) match suspension, voluntary severance offers, a hiring pause, and five days’ unpaid mandatory leave in late December. These are only applicable, however, to non–union members.

The timing of these cutbacks is disturbing. The midterm elections are less than a month away. Partisan and pink-slime “news” networks are blurring the lines between journalism and campaigning while posing as legitimate local news sites, according to the Tow Center’s own reporting. The US is shedding local newspapers at a rate of two per week, which is deepening America’s divides and expanding news deserts.

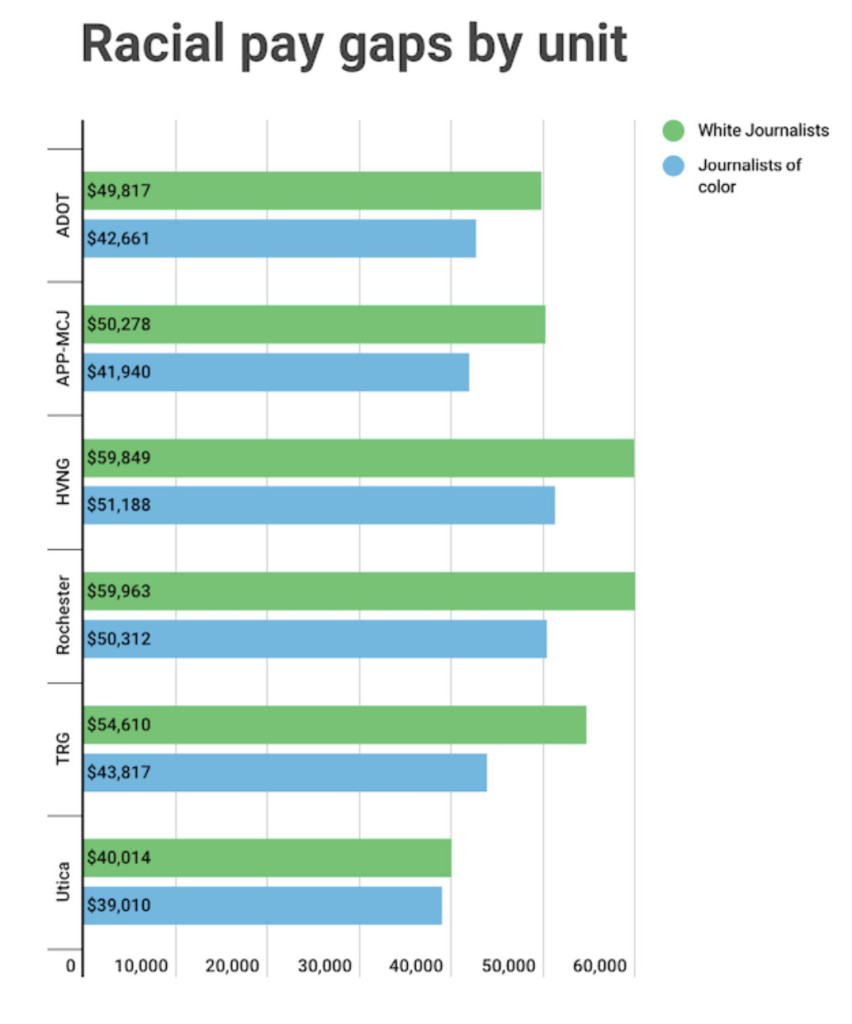

Today, the NewsGuild of New York published a pay study in six Gannett newsrooms in the Atlantic region that shows deep wage inequities across gender and racial lines despite the company’s commitment to diversity.

Parallel to these crises, though, is a historic movement to unionize newsrooms across the country. While Gawker is often credited for kick-starting this revolution by becoming the first digital media company to unionize, in 2015, other digital outlets, broadcast stations, and local newspapers have since joined the movement in droves. One in six US journalists are currently part of a union, according to recent findings from the Pew Research Center, and more would join one if they could. And only days before Gannett made its latest round of cuts, the NewsGuild of New York organized a virtual “Rally to Save Local News” that provided a public forum for Gannett journalists and others to speak out about worker conditions and Gannett’s flailing business model.

While unionizing has its limitations amid the decline in local news—a crisis characterized by a myriad of complexities—the back-to-back Gannett cuts provide some indication that unions can both protect newsroom workers on bread-and-butter issues—like immediate job protections—and safeguard the industry more broadly.

Background

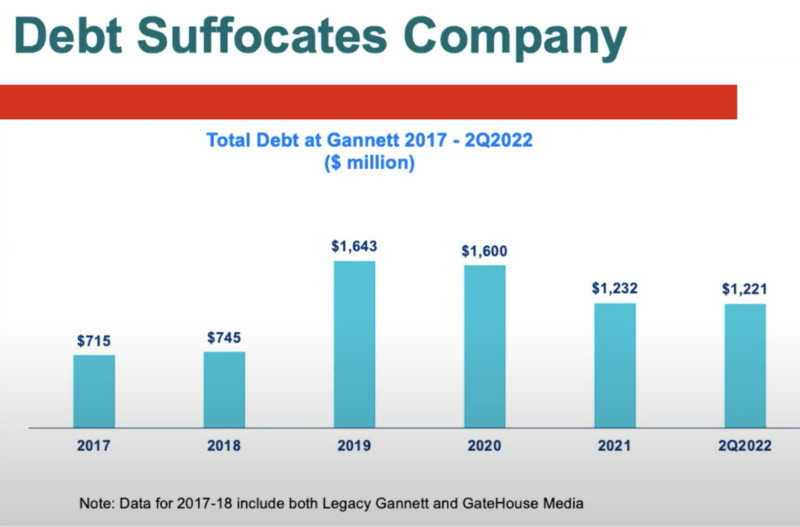

Gannett’s 2019 merger with GateHouse Media made it the largest US newspaper chain, owning and operating more than 250 newspapers across 46 states: about a fifth of all local papers. The private-equity-backed media chain, in a deal totaling around $2 billion, also agreed to acquire GateHouse’s more than $600 million of high-interest debt.

The media conglomerate has also developed a reputation for relentless cost-cutting in its newsrooms. In March 2020, at the outset of the covid-19 pandemic, Gannett announced furloughs and pay cuts that reduced salaries by as much as 25 percent. Less than a month later, Gannett notified workers that as a result of the merger, an unspecified number of workers would be laid off. (The Tow Center, however, found that at least eighty-one employees were laid off in a report on the economic impact of the coronavirus on US newsrooms.) As news of these layoffs spread that week, GateHouse Media’s share value rose 23 percent. In 2021, the number of Gannett employees fell 24 percent, far exceeding the headcount decline of about 17 percent each year since 2018.

The latest October newsroom cutbacks sparked immediate outcry from Gannett journalists and the news industry more broadly.

Many were quick to point out that Reed earned $7.74 million in 2021 alone, more than 160 times the median Gannett employee’s salary, according to the Boston Business Journal.

A government watchdog reporter at the Register-Guard in Oregon thanked Gannett for the wedding present. A travel reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel tweeted that she received the news while sitting in her basement in the middle of a tornado warning. And a Knoxville News Sentinel photojournalist characterized the cuts—specifically the unpaid time off in late December—as Gannett’s version of a holiday bonus. The commonality between these and several other tweets, however, was a shared sense of gratitude for some newsrooms’ unions and the protections that came with representation.

Reed has called the NewsGuild a “big problem.” In 2019, he told the New York Times that the Guild wants to “do business like it’s 1950” and “until [Gannett] can get them to sit at a table and have a real discussion about where the world is today, there’s going to be inefficiencies.” Gannett has also dragged its feet in union contract negotiations for as long as three or four years in newsrooms like the Arizona Republic and the Akron Beacon Journal, respectively.

Some, however, attribute these cuts to Gannett’s financial mismanagement. There are also frequent accusations that the media company prioritizes shareholders over journalism.

Jon Schleuss, president of the NewsGuild-CWA, responded to the October cuts in a press release that read, “Gannett only cares about cutting costs by bleeding newsrooms dry.” Schleuss also said, unsurprisingly, that the only way to fight back is to build a strong union in every newsroom.

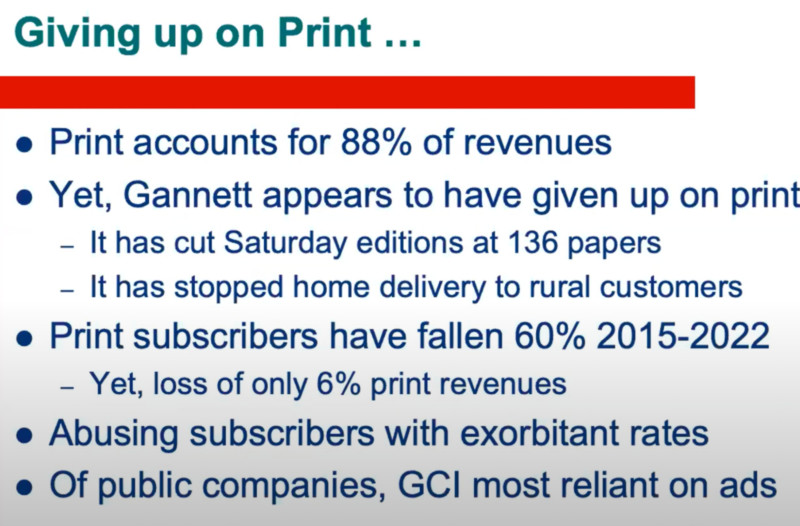

Edd Pritchard, a veteran reporter at the Canton Repository and president of the Northeast Ohio NewsGuild, believes Gannett leadership runs on assumptions about the economics of news. In an email to the Tow Center, Pritchard said that since arriving in Canton, Gannett has been “starving the cash cow while it chases elusive digital dollars.”

Pritchard also told Tow that Gannett has willfully ignored the print side of newspapers, which has resulted in price hikes and near-constant delivery issues. The loss of once-loyal readers is often blamed on newspapers’ inability to adapt to the Web rather than Gannett’s own strategic inadequacies, Pritchard added.

Chart presented by NewsGuild-CWA economist Tony Daley at the virtual Rally to Save Local News. (GCI is the symbol format for Gannett on the New York Stock Exchange.)

Szkolar expressed similar sentiments. “I have zero confidence in [Mike Reed’s] ability to actually lead this company into something that’s sustainable long term,” Szkolar told Tow. “In my nine years [at Gannett], it feels like all they want to do is make some flashy moves, make a lot of money from boosting stock prices temporarily, and then, when things inevitably go awry, they [take off] in a golden parachute.”

The limitations and possibilities of unions

Unions, however, can only do so much to protect news workers amid a decline in local news. For one, only a small proportion of newsrooms, especially at the local level, are currently unionized. The latest Gannett cuts also prompted some to point out that middle management and above, such as editors, cannot be included in bargaining units and therefore aren’t offered the same protections as journalists.

However, Errol Salamon, senior lecturer in digital media and communication at the University of Huddersfield, UK, told the Tow Center that while unions don’t cover everyone, they “still have the power to set the broader agenda.” He added that, “in other words, union gains within the news industry can benefit the entire industry, not just the individual members of that particular union.”

According to Jessica Mahone, research director at the University of North Carolina’s Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media, last week’s Gannett cuts are also evidence of why unions are necessary. “There are people who, were it not for their union, would have gotten that announcement Wednesday and they would not have been protected,” Mahone said, which could’ve been “absolute devastation” for some.

Salamon believes that companies like Gannett can continue to do whatever they want without the collective power of unions. “Although unions alone aren’t going to save the news industry,” he said, “without having that kind of collective power, collective support, and collective public action, companies and management are left on their own to do what they want, and that can make the situation worse for the news industry and workers.”

New union pay equity study

Gannett’s problems extend well beyond its business model.

Despite Gannett’s public commitment in 2020 to foster a “culture of inclusion” for women, people of color, and other underrepresented groups in its newsrooms, inequities persist.

The NewsGuild of New York’s pay study, only the second analysis of its kind, released today, was based on data provided by Gannett in August for both union and non-union employees represented by the Record Guild, the Atlantic DOT Guild, the Hudson Valley News Guild, and the APP-MCJ Guild—all certified in 2021—as well as the Rochester Newspaper Guild and the Utica Newspaper Guild. Together, these units represent more than two hundred employees at nearly a dozen local newspapers.

The NewsGuild found pay disparities between white journalists and journalists of color in nearly every newsroom included in the study. This amounted to median salary losses of around $11,500 per year for journalists of color, who made $43,426 compared with $54,928 for white journalists. The gap widens when comparing white men and women of color, where the median disparity is over $12,200.

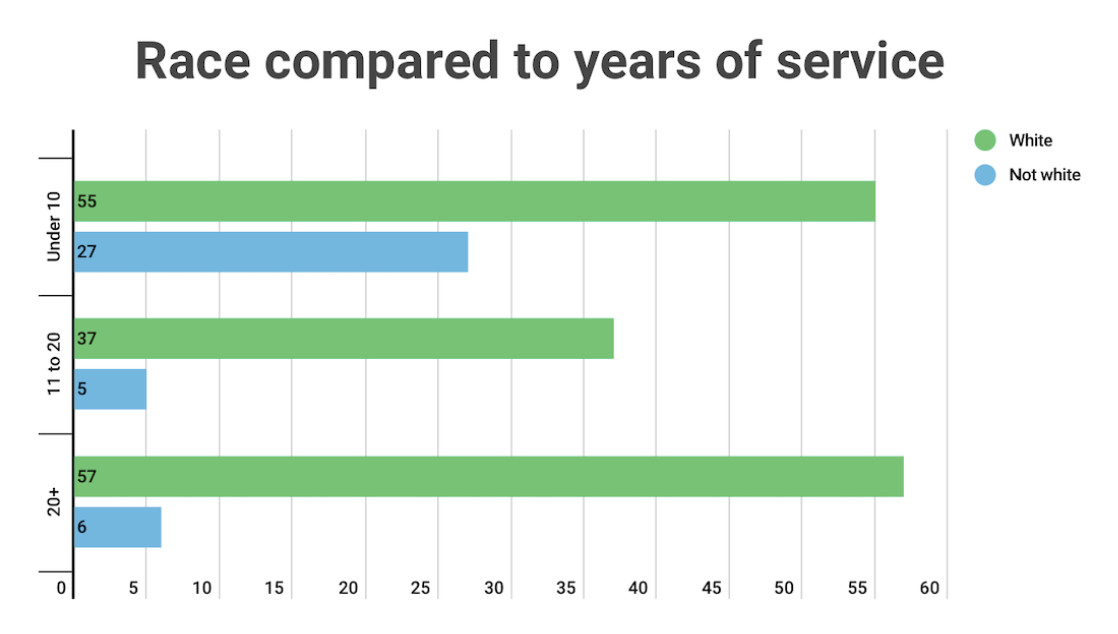

The data also show that few nonwhite journalists make it past a decade of service. The NewsGuild study attributes this trend, at least in part, to the long-term impacts of both the racial pay gap and wage stagnation for mid-career journalists of color seen across every Atlantic-region newsroom included in the study.

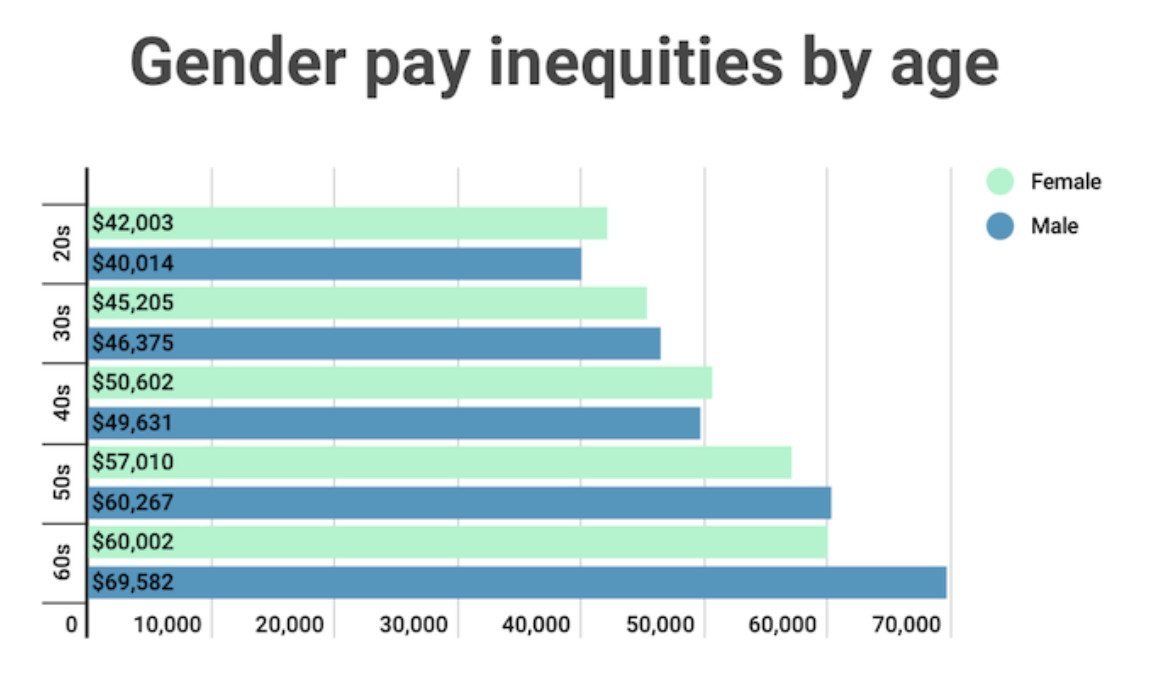

Experienced women journalists are particularly vulnerable to pay inequities. The NewsGuild found that wages begin stagnating significantly for women journalists with over five years’ experience. By the time women journalists enter their sixties, they are earning around $9,500 per year less than the median salary of men.

Szkolar, the USA Today producer, says that if Gannett is really serious about its commitment to a diverse workplace, “they have to pony up and be willing to invest in newsrooms,” which means paying journalists a living wage.

A Gannett spokesperson, in response to Tow’s request for comment on the pay study, said only that “Gannett is committed to ensuring equitable employment practices for all employees.”

Salamon, however, emphasized that diversity and inclusion goes well beyond analytics and quantitative measures and that media owners should also prioritize the subjective experiences of individual workers. This can include things like workers’ ability to provide input into editorial decision-making, which the unions can help facilitate.

The union fight continues

Pritchard says the fight for worker protections is difficult when Gannett continues to unilaterally chip away at different parts of the newsroom. “We can tell them that we don’t think this is a good idea, we think you’re violating our contract, but if they aren’t gonna listen to you, sometimes it’s like telling an alcoholic, ‘Hey, you really should stop drinking,’ and they say, ‘Eh, I don’t care, I’m going to keep drinking.’”

Szkolar believes it’s up to workers to save Gannett-owned newsrooms from their owners. “I think the general feeling in our industry right now is like, ‘No one else is going to help us, so we have to help ourselves.’”

In the meantime, non-unionized Gannett workers face immediate cuts—like the 401(k) match suspension—while others weigh their options to apply for voluntary buyouts. If its proposal is accepted, Gannett has indicated paid-out workers could be dismissed as soon as November 4, or the Friday before Election Day.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.