Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

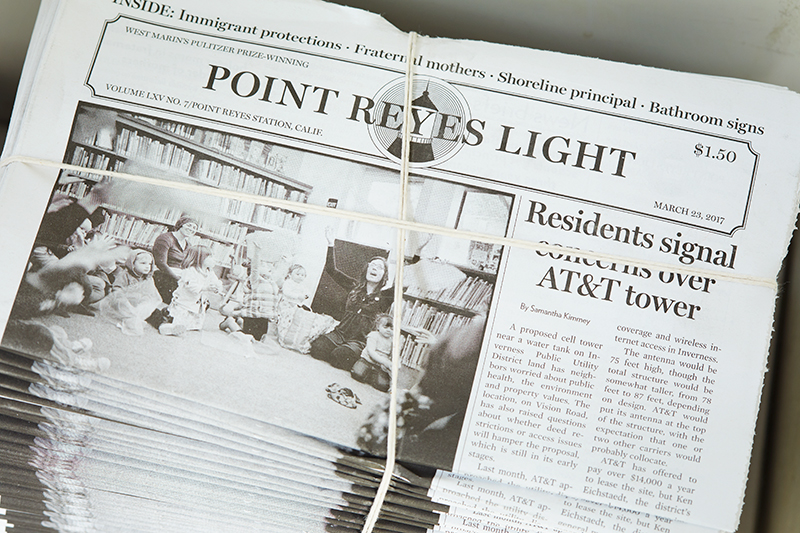

Wednesday is production day at the Point Reyes Light, a weekly newspaper based in the town of Inverness, just over an hour north of San Francisco along the bucolic, switchbacked coastal roads of West Marin County. In the middle of the Light’s skylit newsroom, lined with heavy wooden desks and filing cabinets containing years of old issues, five staffers are in various stages of completing the week’s stories and layout. Near the front of the office, the paper’s editor in chief, Tess Elliott, a slight, fine-boned woman with a tangle of auburn hair, frowns as she proofreads the Sheriff’s Calls page.

The police blotter is a fixture in many local newspapers, but it’s safe to say that most haven’t gotten quite as much attention as the Sheriff’s Calls. Compiled and written by Elliott, who has been running the paper for a decade, the column has inspired two short-story collections by a local writer and, more recently, national coverage by Slate (“The Best Police Blotter in America”). A New York literary agent has called Elliott about doing a book; the Oakland Museum of California has asked her to give a talk; one Bay Area writer wanted to collaborate with Elliott on a coffee table book. She hasn’t pursued any of these—largely because she doesn’t have the time, but also because she doesn’t want readers thinking that she is taking advantage of their misfortunes.

It’s worth examining what makes the Sheriff’s Calls so compelling, since Elliott says she’s simply paring down the notes from the Marin County Sheriff’s Office. One Sunday in mid-February looked like this:

OLEMA: At 7:50 am a black cow was outside a fence.

FOREST KNOLLS: At 11:28 am a teenager had reportedly come into a store and masturbated while staring at a teenaged cashier.

NICASIO: At 1:40 pm a passerby reported an overturned vehicle near the lagoon.

WOODACRE: At 7:18 pm a man reported an unwanted woman.

With those spare juxtapositions, Elliott manages to turn what goes on in her corner of the world into something of a meditation on the human condition. The unintentionally comic (“BOLINAS: At 12:40 pm a man said his neighbor kept cutting tree branches that hang over their fence and throwing them onto his property”) and the straightforwardly tragic (“STINSON BEACH: At 5:30 pm, a depressed woman felt that she would not make it through the night. Medics took her to the hospital”), are separated by just a few hours and a few lines. It is a temporal window opened, airing the worries of a rural unincorporated area of 16,000 people.

Elliott takes pains to point out that she does not think of the calls as poetry, nor does she intend them to be funny. But she does think of them as a reflection of how we are all subject to pain and conflict, both trivial and major. The calls are an indicator of what keeps a community up at night. In the months since the election, Elliott says, they’ve been getting darker: more suicides, more mental health emergencies. “Some people feel like we live in a bubble in West Marin, so I think it does you a service to read the calls,” she says. “To be reminded that there’s an underbelly—that it’s not a perfect life for everyone out here.”

With just six staff—two of them reporters—the Light is the very definition of a small-town paper. But the paper has the particular distinction of being the small-town paper that won a Pulitzer in 1979, under then-Editor and Publisher David Mitchell, for its revelatory reporting on a local cult. Since then, it has had contentious turnovers in management, including a brawl between Mitchell and his immediate successor, Robert Plotkin, a brash former Monterey County prosecutor who pledged to turn the Light into the “New Yorker of the West.” What ensued reads a bit like the plot of a Coen brothers movie, complete with crosstown feuds and heated rivalries. Plotkin’s managing editor, Jim Kravets, defected and co-founded a competing paper, the West Marin Citizen, in 2007, the same year Elliott took over as editor of the Light. Thus began the so-called West Marin Newspaper War, a rancorous eight-year-period during which the papers took opposing sides on major local controversies. Friendships broke up. Neighbors stopped talking to each other.

In the early years, critics accused Elliott of lacking transparency, stoking conflict, and neglecting basic journalism ethics. She is the first to admit that she was in over her head. By 2015, it was clear that the community wasn’t big enough to support two papers, so Elliott and her life partner, David Briggs, the Light’s photographer and general manager, acquired the Citizen and folded it into the Light, hoping to bring the once-divided readership together. Though there was some angst about the demise of the other paper, “things have calmed down since then,” she says.

‘Everything is very personal to me, in a way that it wouldn’t feel if I were in a big city, where things could be more anonymous.’

Elliott, the one-time outsider and neophyte, has lately, by dint of hard work and endurance, become one of the community’s own. During her tenure as editor, she has tried to restore the original news-oriented, investigative character of the Light. She is keenly aware of the importance of covering what’s important to locals: In this unincorporated area of Marin County, much is governed by service districts and decided by a never-ending parade of meetings about essential infrastructure issues like sewage, trash, and parking—those things, in other words, that no one else would cover. But she also aspires to publish stories with larger-world context. In recent years, several stories appearing in the Light have had wide repercussions: Its coverage of Drakes Bay Oyster Company’s fight to stay in business on federal parkland garnered national attention, and an 11–part investigative series on the flawed science behind the Bay Area’s so-called breast cancer cluster won a 2016 gold award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science. It was pitched to Elliott by writer Peter Byrne; he sought out the Light in part because publications like the San Francisco Chronicle and the Marin Independent Journal had published stories in the past that had not questioned the research.

How does a small-town paper manage to do its work and stay connected to its readership today? For Elliott, 37, it means being crammed into the newsroom from 9 am to 2 pm on Wednesdays with her staff and her toddler daughter, Olive. At 2 pm, she sprints out the door to pick up her son, Elliot, from kindergarten. “It’s really my life, juggling my kids and the paper,” she says. “And because I run the paper with their dad, my partner, it’s all one messy, inseparable thing.”

When I ask Elliott what made her want to run a newspaper, she pauses before answering. “I’m just here by accident,” she says, a bit wonderingly. “And that’s the truth.”

Elliott does not come from a journalism background, nor did she grow up in a small town. But she is sensitive to what it means to cover one’s intimate community. She grew up in Eugene, Oregon, the daughter of a social worker and a naturopath who met at the University of California, Berkeley, while protesting the Vietnam War. As a 5-year-old, she received lessons in meditation. She attended college in Boulder, Colorado, and earned a bachelor’s degree from the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, the writing program founded by Allen Ginsberg and Anne Waldman at Naropa University.

“It was a very alternative school, and much of my degree was in poetry,” says Elliott. In conversation, she often apologizes for fear of seeming scattered, but she is unfailingly attentive and thoughtful. “I studied Buddhism and my minor was in Tibetan language—I studied the language for a long time, practiced Buddhism, and thought about doing translation. Mostly I read religious and philosophical texts. I love languages, and that was partly why I was doing that.”

When she moved to California, in 2004, it was because of a road trip she took to Tomales Bay. She had no real direction in terms of employment, but she felt pulled to the land and seascape of Point Reyes. She tried writing children’s books. She painted houses with a friend. And then, in 2006, she applied for an intern position at the Light, where Editor Robert Plotkin was looking for a photographer.

Elliott was not a photographer, but she had a camera, and she thought it sounded like fun. When she went to talk to Plotkin, she says, he laughed at her portfolio. She left his office feeling deflated. But they saw each other around town and became friendly. He eventually offered her an advertising job on a special section spotlighting local merchants. She quit after six weeks. The sales work didn’t suit her.

She also began to grasp the community’s animosity toward Plotkin. “People did not like Robert—I’d walk into a shop and get an earful,” she says. “I liked him, but I couldn’t endorse what he was doing at the paper. That was hard for me.” Plotkin, who grew up in San Diego and attended the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, was vocal—and yet tone-deaf—about his lofty aspirations for the community paper. He had an outsider’s sensibility and a thirst for sensationalism that deeply offended local residents. His biggest faux-pas might have been a Christmas week edition that featured a disturbing full-page mug shot of an accused rapist on its front page. He says he’d been reading Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood at the time.

In spring 2007, Plotkin asked Elliott to come back to edit at the paper, which had 12 staffers, including a handful of interns, at the time. Jim Kravets had just left to start the Citizen, and he needed someone to take over. Though she had no real experience in newspapers, Elliott decided to try it. “I got a crash course in journalism—some things from Robert and a lot from these great young reporters and interns I was working with,” Elliott says.

Plotkin, for his part, told me it was out of character for him to hire Elliott. “I am an elitist,” he says. “I only hired people from Columbia, NYU, and Medill.” But during that combative period, Elliott’s graciousness and light touch with people was welcome. He could leave the office in her hands and not be afraid everything would burn down. By late 2007, Plotkin had thrown in the towel on day-to-day operations, and Elliott was on her own in covering one of the biggest controversies in recent years, a lawsuit between the National Park Service and Drakes Bay Oyster Company.

A small, family-run oyster farm that pre-dated the establishment of wilderness areas, Drakes Bay Oyster Company was located in a rich, 2,500-acre estuary on the Pacific coast side of Point Reyes National Seashore. It had been grandfathered in as the Johnson Oyster Company and allowed to keep farming until 2012. In 2005, a third-generation Point Reyes rancher named Kevin Lunny bought the farm, renamed it Drakes Bay, and announced that he would seek an extension from the National Park Service. The question of whether the permit should be renewed ignited a local and then national debate over what activities should be allowed in wilderness areas. “The story was just breaking, and the paper was breaking it,” Elliott says. On first blush, the story seemed simple: Environmentalists supporting full wilderness protection under the law were fighting against local ranchers, farmers, and dairies protecting their turf.

It was, of course, more complicated than that. The parsing of what Congress meant by “wilderness” came to the forefront. The 1976 law establishing the seashore as national parkland also recognized the pastoral ranches and dairies as critical to Point Reyes’s historic character. Where did sustainable marine agriculture on the coast fit in? The Sierra Club stated that closing the farm would be the best way to protect the fragile ecosystem. The National Park Service pointed to studies showing that oyster operations were disruptive to bird and harbor seal habitat. But the science ended up being far less conclusive than was portrayed. Notable Bay Area progressives, including Alice Waters and Michael Pollan, supported the oyster farm’s continued existence as the ideal model of man working with nature, not against it.

The more time I take as an editor to explain my thinking . . . the more trust I feel from people. I’m trying to be less defensive.”

Summer Brennan, who grew up in West Marin, worked as a reporter at the Light in 2012, and later wrote a book called The Oyster War, has described the conflict as “a Rorschach inkblot test”—people in the community “saw within it their own fears and prejudices.” The fight dragged on for years. The Light under Elliott drew supporters of the oyster farm, while the Citizen under Kravets drew supporters of its closure. Elliott, still inexperienced as a journalist, was overwhelmed.

“Early on, I didn’t know what I was doing, and in the midst of this intense debate and this difficult-to-grasp story, feelings were really inflamed,” she told me. She admits she was swept up in the conflict and was not entirely prepared to guide the reporting; eventually, she became a strong advocate for the oyster farm through editorials.

Kravets, who left the Citizen in 2010, tells me that he knew Elliott was learning on the job, but it led to problems. “She was largely unfamiliar with journalistic ethics, particularly when it came to the distinction between news and opinion,” Kravets says. “As the Citizen was covering the same stories with the same source documents, it was easy for me to see how and when the Light selectively chose facts to tip the editorial scales.” Instead of presenting the facts in a fair, unbiased way, Kravets says, Elliott was practicing advocacy journalism.

Complicating things further was the fact that Elliott had become personal friends with Corey Goodman, a scientist and entrepreneur on the side of the oyster farm who during this period also was leading a successful effort to purchase the Light from Plotkin. Elliott was getting ready to jump ship when Goodman persuaded her to stay; he, along with former Mother Jones Editor and Publisher Mark Dowie and other investors, formed the nonprofit Marin Media Institute to buy the paper in 2010. With a business structure modeled on Poynter’s relationship with the St. Petersburg Times (now called the Tampa Bay Times), the Marin Media Institute had nine board members and stated that its educational intention was to train people in “village journalism,” while a low-profit publishing arm, with Elliott at the helm, was to run the paper. Critics viewed the complex ownership structure as opaque, and readers became distrustful of who was making editorial decisions—especially when it came to Drakes Bay.

Kravets says that Light reporters leaving their jobs under tumultuous circumstances complained to him that Elliott demanded changes to their oyster articles that to them seemed dishonorable. Brennan, one of those former reporters, says she felt uncomfortable with the editorial process as dictated by Elliott. She left the paper after five months.

Elliott admits that the newspaper war and the Drakes Bay war merged in an unfortunate way. Kravets once attacked Elliott in a series of editorials for the Citizen. “The theme was that I was too cozy with Corey Goodman, a main activist in the Drakes Bay controversy, and others on that side of the debate,” Elliott tells me. “He was right, but it was also really hard not to be compelled by the data that Corey called out.”

The conflict dragged on for years, ending only with the farm’s closure in December 2014, two years after former Interior Secretary Ken Salazar refused to renew Lunny’s permit and six months after the Supreme Court declined to hear the case. Last August, the restoration of the estuary began with the removal of an estimated 500 tons of oyster racks and marine debris.

It does say something about Elliott that, when I ask her who her harshest critics have been, she sends me a list of names and offers to put me in touch with them. When I tell Kravets that he was on that list, he says that he gives her tremendous credit. In his eyes, she took a principled stand against what many in the community perceived as injustice and government abuse directed at Drakes Bay Oyster Company. But it wasn’t unbiased news coverage.

Much of Elliott’s maturation as an editor over the last five years—her renewed focus on transparency, her less frequent editorials, her awareness of public perception when it comes to conflicts of interest—is a direct result of being burned by that time. Since 2015, the Light has been run by an LLC of which she is the sole member. She purchased the paper from the failing Marin Media Institute in exchange for $100,000* in back wages she was owed. To buy the Citizen, she and Briggs raised another $50,000 from donors.

“Everything is very personal to me, in a way that it wouldn’t feel if I were in a big city, where things could be more anonymous,” she says. “I’ve learned that transparency is the key. The more time I take as an editor to explain my thinking, to be open about my thoughts and opinions, to apologize for and correct mistakes, to talk about my limitations, my struggles, and my vision for the paper, the more trust I feel from people. I’m working on being less defensive.”

David Mitchell, dubbed the godfather of West Marin journalism, is still a close observer of the paper he ran for nearly 30 years. “There certainly have been some major issues, contentious ones, and Drakes Bay Oyster Company was one of them,” he tells me. “Do you want to have a paper turning out a ‘he said, she said’ story, or do you want to have a paper that’s digging into what’s really going on? Here’s what people are saying, but look at the facts. That’s what I would prefer. But I think the paper has been more investigatory under Tess’s direction. She came in not having much experience at all in newspapering, and has had to learn on the job, and by most people’s assessment, she’s done a good job. I think some of the rancor has burned off.”

These days, the soundtrack to the Light’s newsroom is one of classical music and the chatter of a police scanner, punctuated by the occasional phone call and conversation with 17-month-old Olive, who roams around the desks inquiringly. I ask David Briggs if he ever chases down leads from the scanner. “Rarely,” he says. “Unless it’s right here in Inverness—it’s hard, since things are so spread out here. We don’t have enough people for that.” He pauses, listening to a report of smoke and fire near Nicasio Reservoir.

Something familiar clicks in the description and all five staffers in the office look at each other and laugh. “There are these feuding neighbors,” Briggs explains, his eyes lighting up. “One of the farmers is using propane to blow up gopher holes.”

The precipitous decline in staff and funding for daily operations is, to say the least, challenging. Revenue comes mostly from advertising (in 2016, $309,000 came from advertising, $109,000 from subscription and paper sales). Elliott helps deliver the papers on Thursday mornings. In the last 10 years, she has gone through a couple dozen reporters and interns. The rate of burnout is high, the pay abysmal. Elliott’s managing editor and most experienced reporter, Samantha Kimmey, 29, has been with the paper for four years. She is leaving in May, in part to deal with health issues. “As much as I love the Light—and I do, and I have cried over this decision to leave it, because it is my home—I would like to work on stories that have a broader scope and let me dive deeper than the weekly schedule allows,” Kimmey tells me.

When Kimmey departs, she will take years of hard-won community knowledge—the slow accumulation of intimate details, like the backstory of that fleeting police scanner report. And that’s only getting harder to replace.

Elliott and Briggs live a two-minute drive from downtown Inverness, up the hill from Tomales Bay, in a house above the tree line with big, light-filled windows. They have a kind landlord who charges them below-market rent. When I visited Elliott at home on a recent Friday morning, we talked in the toy-strewn front room while her children played with green and purple Mardi Gras beads sent by Briggs’s parents, who live in Louisiana.

“A paper is a really critical part of a community’s sense of itself, but everybody who’s working here hardly makes any money,” she says. “Our children come to work with us in part because we don’t make enough to afford childcare. David spends one day a week cutting trees. He develops film in our closet. And everybody else, our business assistants, are mostly retirees who want to make a little extra money. So that’s the other big piece: How do you make this work economically?”

The award-winning series on the Bay Area cancer cluster was funded in part by Kickstarter, and Elliott spent much of her maternity leave with Olive editing it, without pay. “It’s all we can do to cover the daily updates on weekly stories,” she says. “But I want to do the deeper stories, too.”

Elliott thinks the national conversation about newspapers is now evolving to include how they can bring us to common ground. She has seen the Light into what now seems to be a calmer, more united period. The latest controversy has to do with a new lawsuit brought by three national environmental groups against the National Park Service over ranching rules. Unlike Drakes Bay, however, there is agreement between the West Marin environmentalists and the ranchers. “People use the paper, and we run a lot of letters,” she says. “We have some new unity around the ranchers that we didn’t have a couple of years ago. And I would like to think that we’ve got something to do with that.”

For about nine months after the sale of the Citizen in 2015, West Marin residents sent story tips to Jim Kravets’ personal email address because they didn’t trust the Light’s coverage, despite the fact that he had not been involved in the newspapers since 2010. But those emails have trailed off.

In this post-election reality, what can a community paper do, or be, with the uncertainty around immigration and other issues acutely affecting West Marin? “We have a huge immigrant population that we’re completely dependent on, and a local school district that’s more than 50 percent Latino,” Elliott says. She has been thinking about how to develop a Spanish-language edition to more directly connect with those residents. “Right now, we’ve been reporting on meetings and presentations on immigration and civil rights, on political organizing that’s getting underway, and giving space for op-eds and letters from people who are connecting the dots or encouraging or describing their activism.” The changes in the Environmental Protection Agency are sure to affect this piece of the coast. She is certain that residents will have a lot to say.

The Light, it must be said, still works for reasons that are not sustainable. Talented people work for below market pay. The paper was rescued from failing nonprofit status. It navigated the acquisition of a competing paper. It has an especially civic-minded and engaged audience that relies on it for critical information. In other words, it works because of exceptional circumstances, and exceptional people.

Kravets, of all people, offers a benediction of sorts. “When it comes to community newspaper editors, it’s impossible to overestimate the importance of durability, and Tess has proven the most durable of editors,” he tells me. The job demands a steel spine: Half the community hates you each week, and if you’re doing the job right, next week it will be the other half. “Her endurance through some of the most contentious chapters in West Marin history speaks volumes. At this point, her institutional knowledge is incalculable, and she has earned every bit of it.”

*Correction: This story originally stated that Elliott purchased the Light with a $50,000 waiver of unpaid wages. The waiver was actually for $100,000 of unpaid wages.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.