Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

In a survey of about seventy people working in American newsrooms, conducted by the Arab and Middle Eastern Journalists Association (AMEJA), journalists of Middle Eastern and North African descent described facing intensified levels of scrutiny since October 2023, with the start of Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. AMEJA published the results of its research as the ceasefire went into effect, marking a time for reflection on press coverage of the war. “We put together a survey because, as journalists, we always try to uncover the truth,” Aymann Ismail, the president of AMEJA and a staff writer at Slate, said. “Rather than talk about it, we wanted to see what the actual metrics were, and we wanted to see if this is something that was being experienced across the board.”

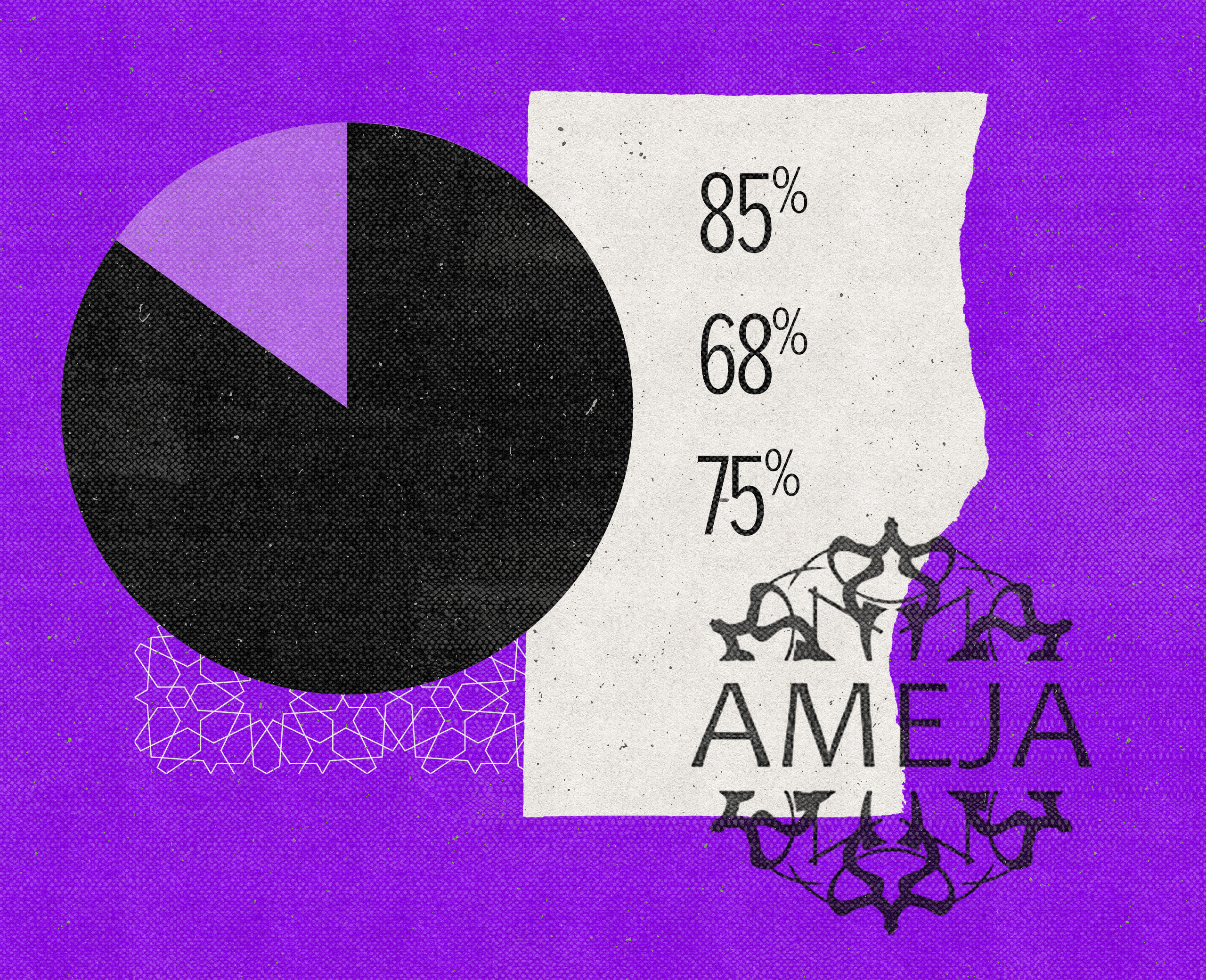

The results were striking: 68 percent of respondents reported noticing changes in how editors assigned or framed their coverage of the Middle East; 85 percent said that their reporting on the Middle East and North African (MENA) region had been held to a “higher standard of neutrality.” Three quarters of those polled said their newsrooms applied standards of objectivity unevenly, based on background or identity; 75 percent said they frequently or occasionally “self-censored their language and reporting due to fear of backlash,” and 44 percent reported an increase in online harassment.

AMEJA, which aims to support a sense of community for journalists who come from or report on the MENA region, views the survey as evidence of a news environment marked by suspicion and fear. Ismail traces the problems to newsroom stewardship: 60 percent of respondents said they believe MENA journalists are underrepresented in leadership roles within their organization. “There is a correlation here, especially when we look at who is assigning, editing, and fact-checking stories,” he said.

There are less structural, more practical steps news organizations can take to address the challenges staff members face: for instance, to curb online harassment, Ismail suggested, newsrooms could provide staff with resources that wipe their personal information from the internet. “These are solvable issues,” he said. “By presenting them, we’re going to find a lot of alignment and agreement in the journalism world that this is a problem, and that this does need to be addressed—not just for the sake of reporters, but for the sake of improving the journalism being produced about the region in the first place.”

Roughly a hundred people responded to the survey, but not all were of Arab or Middle Eastern descent, so the organization filtered the replies to focus explicitly on the identity of those from the region. “Having somebody who is Arab or Middle Eastern report on these regions gives publications a special kind of access,” Ismail said. “That’s not to say you need to be Arab or Middle Eastern to report on the Middle East, but if you have somebody who already speaks the language, who grew up in steeped in the culture, who might understand some of the informal cultural aspects of the community they are reporting on, you might then create a situation where you’re able to get better quotes, and better access to a community.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.