Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

A political rally is a forum to meet supporters—but it is also, inevitably, a media event. The other day, when Donald Trump met a crowd in the suburbs of New York, credentialed members of the press vied with hordes of social media personalities, of varying journalistic ambition, for interviews. Among them was Dylan Palacio, a thirty-year-old former college wrestler from Long Island with about thirty-two thousand followers on Instagram. “For the last twenty, thirty years, you had news networks,” he said. “I think moving forward, people are the news networks. You’re seeing that with YouTube. I could be ‘Dylan Palacio.’ That’s my network. People want to tune in to people.”

Palacio arrived with a placard that read, “Undecided voter. Win my vote.” He wore a bright red Cornell golf shirt—he’d gone to college there—and a matching Trump 2024 visor, with a wig of bleach-blond hair that plumed from the top. Two friends tagged along; one became his iPhone videographer. They stationed themselves a little distance away from the serpentine queue leading into Nassau Coliseum. Soon, Palacio was approached by Trump fans angling to make their case. “If you believe that Kamala should be president, you need to open your eyes,” a middle-aged man advised.

“Okay,” Palacio replied. A guy in a red “Make America Great Again” cap with “45-47” inscribed on one side asked that he consider the plight of cats and dogs in Springfield, Ohio. “The informational integrity of all of the sources on that are shaky,” Palacio suggested.

“I don’t think it is a shaky source,” the man countered, “when you can see a video recorded by a guy who has no racial or political or other motive to lie or to defame these people, who is taking a video of something in the backyard next to his house.”

Palacio nodded. “Do you think people have an incentive to lie for social media attention?” (The man did not.)

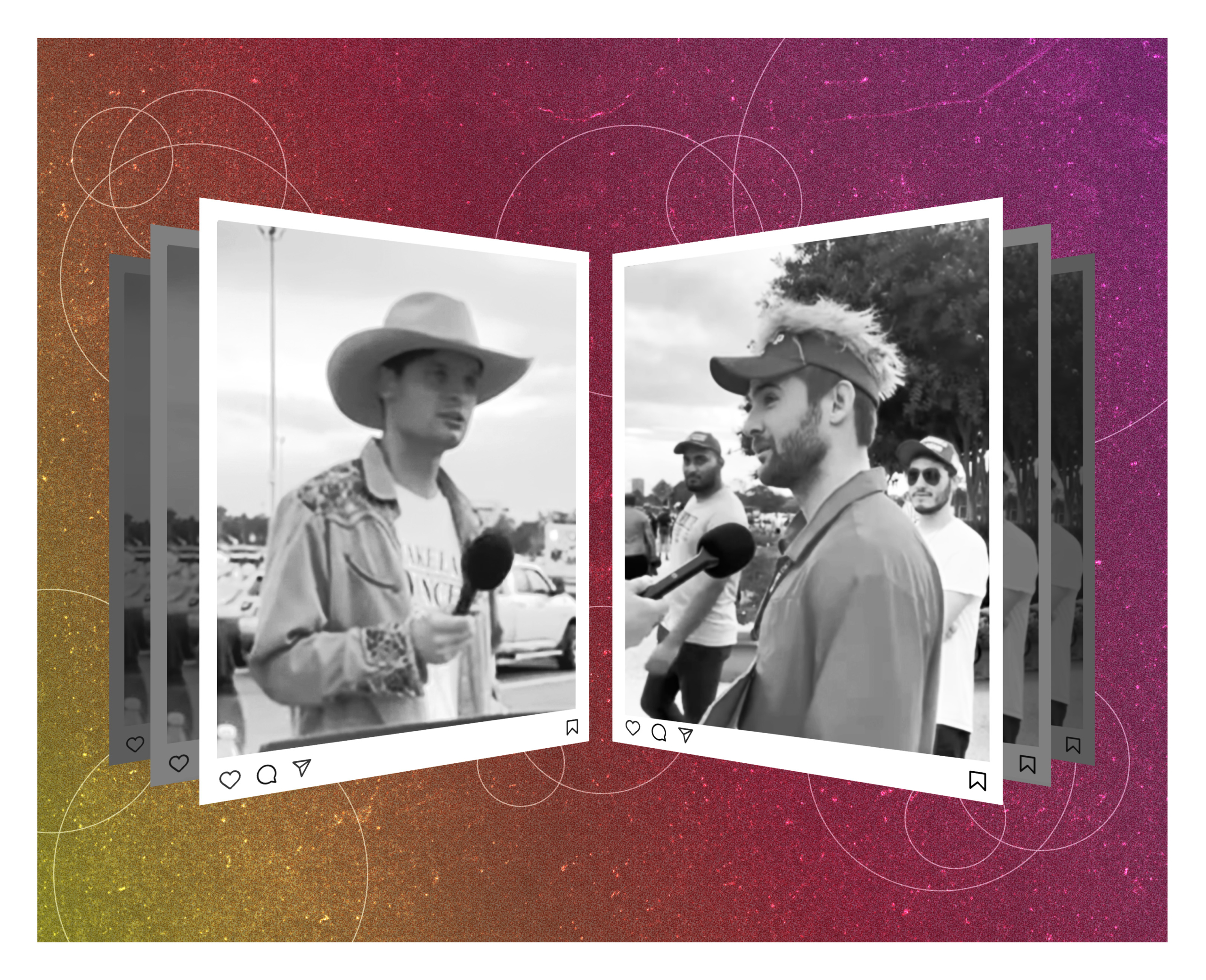

A while later, Palacio was approached by a lanky dude in a cowboy hat and a turquoise overshirt embroidered with flowers; underneath, his T-shirt advocated lap dances in MAGA verbiage. “Do you like pets being eaten?” he asked Palacio. And then: “Do you like peeing with the seat up?” The cowboy was Lionel McGloin, a comedian, who runs an Instagram page called NO CAP ON GOD, with more than 145,000 followers and the tagline “Real journalism.”

The camera guys for each of the dueling social media personalities began filming. This was a content opportunity for both accounts. Palacio turned McGloin’s questions back around on him: “Have you?”

“No,” McGloin said. “I haven’t. But that’s what you’re supporting when you’re undecided. You’re undecided about whether that’s good or bad.”

“It’s, like, a bit,” Palacio said later. “He wants to act really stupid and suck in the most polarizing people.” Palacio was game, but he views himself differently. He’d been at Cornell during the 2016 presidential election, and remembers how shocked his classmates had been about the outcome. This time around, he wanted to get a better sense of where voters’ heads were, including ideologues at a rally. “There’s something to listen to—good or bad,” he said. “I’m genuinely interested in where the needle is at a place like this.”

Do earnest Instagram interviews pay the bills? Palacio said that he makes a living from “a variety of entrepreneurial adventures” and by having been “an early Bitcoin guy.” That generates enough income to offer, for other man-on-the-street posts, a thousand bucks to anyone who can beat him in a wrestling match. He didn’t attempt that at the Trump rally. “The political temperature is very high,” he said.

The place was teeming with people covering the scene for social media, in one way or another. There was a woman who went by Aimee Marina (not her real last name), who identifies as a reporter, with a Substack, “No One You Know,” and a YouTube channel, “NYC For Yourself.” (She has twenty-seven hundred subscribers on YouTube; her most popular video from the rally garnered twenty-eight thousand views.) She, too, winced at the instigators among her ilk. “People go out and try to get the people that they interview to say something stupid or ridiculous on camera,” she said. “I think that is really destructive to our public discourse.” She likes talking to strangers about the goings-on in politics and public health, with a special interest in “vaccine mandates.”

Yoni Kletzel, who is twenty-seven, fills his Instagram account—he has thirty thousand followers—with street interviews about Israel and Palestine; he describes himself as doing journalism to “some extent.” (At least one of his videos was paid for by a super-PAC called the Republican Jewish Coalition Victory Fund.) A guy known on Instagram as Movie Moe (thirty-six thousand followers) arrived with a cameraman who egged interview subjects on while he did the talking (“Get her to do ‘Four more years!’”). Moe is striving to be the “best livestreamer, mainstreamer, and independent journalist,” he said.

None of the aspiring social media correspondents mapped neatly along traditional political lines, their coverage a jumble of current events and cultural commentary. What they seemed to have most in common was enthusiasm. Still, they are quick to sniff out colleagues’ attention-seeking. “At the end of the day, what these people want to do is dunk on people,” Palacio said, after he’d posted his Reels. “They want sound bites from the most polarizing of people. Because that is the financial model of social media, unfortunately.” Then again, he added: “They took a page right out of Fox.”

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.