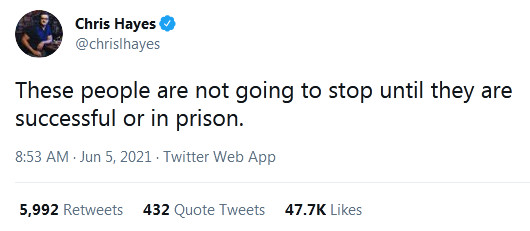

Those who have been following Chris Hayes’s coverage on MSNBC understood the above tweet to mean that by “these people,” Hayes was referring to the Trumpist faction of the GOP, hell-bent as it appears on keeping the government in thrall to itself. Hayes is convinced they will not stop until they either succeed in overthrowing democracy in the US or are sent to prison.

MSNBC has not settled on a consistent position regarding this question—which is a historic question, and not a “news” question open to conventional analysis. To put this another way: Hayes’s tweet is either true, or not. If the Republican party has in fact been hijacked by authoritarians, we are facing one reality, and if it’s not, another and very different one; the two views are so fundamentally irreconcilable as to foreclose on the idea that “reasonable people can disagree.”

Despite the failure of Republican leadership to permit even an investigation into the January 6 insurrection, MSNBC’s habitual politeness—its bias toward “balance”—is as prominent as it’s ever been. So how to square that fact with the views of one of the network’s prime-time anchors on the threat of encroaching authoritarianism?

I spoke with Hayes last week to clarify his views on these questions. The following has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Maria Bustillos: There’s an apparent disinclination to state the facts plainly in media, with respect to the current situation in the GOP.

Chris Hayes: Part of it, I think, is that reckoning comes with definitive defeat and concession. The most obvious example being Nixon, resigning and getting on the helicopter.

Yes, Nixon was pardoned by Ford, but a lot of the people around him went to prison. And it also occasioned an intense national reckoning: how could it have happened that this man became president and did what he did? And out of that reckoning we got the Church Committee, we got FISA, we got basically the structure of modern campaign finance regulations and the birth of the FEC; there was a multifaceted look at the weaknesses of American governance, at [the reasons why] Nixon was able to abuse state authority in the way he did. And we need that again.

In the end, everything held just enough. But you know, they’re gonna keep pressing until it doesn’t hold. Michelle Goldberg had an opening line in her New York Times column the other day that I thought was so good, about being in the eye of the storm of American democratic decline.

[Goldberg’s actual phrase was “American democratic collapse.”]

And it’s funny, because the first time I was actually in a real Gulf hurricane—Hurricane Irma—I knew, intellectually, when it was the eye of the storm. But when I went outside, during the eye, I literally had to keep telling myself that this was the eye. Because it did feel like a gorgeous day, like the storm was over; I knew it was the eye but perceptually, viscerally, emotionally, I was like: it’s gone. Maybe we got it wrong. Maybe the storm actually passed.

Because that would be nicer.

It would be nicer, and also that’s what it feels like, day to day. When you had [Trump] in the White House, particularly during the worst of COVID, the urgency of the crisis, the mounting death toll and the omnipresence of this horror was so suffocating.

And now it’s like… the threat hasn’t gone anywhere, but it’s harder to will yourself into feeling it that way.

In your tweet you referred to they—it’s they who are not going to stop. It’s not one person.

I agree; [Trump] is uniquely sociopathic, but his sociopathic qualities fit perfectly with what the movement wants, which is why he has been raised up by that movement. The crisis in America right now, to me, is the controlling faction of one of the two major political coalitions that is radicalizing against democracy.

And it’s not the full coalition, right? It’s a faction, but it’s a controlling faction, like… the Bolsheviks were just a faction. And they took the Winter Palace with so few men, so… that’s the worry.

If we really are in the eye of the storm, then clearly an immediate and total re-envisioning of news coverage seems essential. But institutional journalism is disinclined to perform what it thinks of as an “activist” role, or really anything challenging the notion of “objectivity.” So what do we do?

I don’t know. I can only do what I do; I focus on what I feel like is the urgency of the moment. I do think there was a recognition broadly across the press, the media, of the urgency of the crisis, particularly in the last year, between COVID and January 6th.

I think fundamentally I don’t see it as a press problem so much as like, a malformation of one of the two coalitions. Within the boundaries of how the press largely views itself, it’s been fairly forward-leaning about this sense of crisis and urgency.

The problem is, there’s two parties, and there’s two coalitions, and one of them is just… okay with this. And then it just sits there, in the middle of American life. In the middle of American governance. And it’s very hard to figure out how to talk about that.

But I mean, it shouldn’t be.

I don’t have the power to throw anyone in prison, all I have the power to do is sort of bear moral witness to what the stakes are as I see them… I’m not democratically elected, I’m not a member of the state, I haven’t been constituted by the demos to mete out that role.

You’re a citizen and you can demand justice.

Right, I mean… it’s hard, though, and this is where we get into these thorny institutional questions. [For example], I saw an interview with one of the Manhattan DA candidates, and she was being pressed to make a commitment to prosecute Trump. And I found myself tied into knots about whether you should say yes or not. One side was like yes, clearly. But the rule of law, and the traditions we have around prosecution, are in tension with that. So it’s a very strange moment.

What would be the signal that we’re going back into the storm, to you?

I don’t know. I have to say, I’ve been so knocked around by the last few years, maybe it’s because I came of age—my last college years were in the late nineties, the global victory of neoliberalism, The End of History, Fukuyama, the dot-com bubble—and then 9/11 happened, and I just had no expectation of normalcy, or the boat getting back onto an even keel.

So I have no idea what’s coming. There’s an enormous array of possibilities. But the fundamental threat to the American small-d democratic project is before us every day, and naming that and being vigilant about that is what I think my role is.

The sheer relentlessness of this junta, or whatever it is, I have no idea what to even call it, has been very easy to underestimate. So you’re like seeing this thing unfolding in front of you, and I feel like I watch television and it’s just not named.

I think it’s a hard thing to name. The other thing I will say about this is that different people have different theories about how bad it is, and where we’re at. And there’s lots of people, like I saw Dianne Feinstein saying this the other day, and even [Justice Stephen] Breyer—look, I mean I don’t bear folks that take the other view of this any ill will or malice, and at some level I hope they’re right… I kind of want to be wrong, and, and I do question myself. I mean, I wonder—am I being melodramatic here, like… is this—?

But three hundred thousand people died unnecessarily, and that culminated in a violent assault to install the loser of an election over the winner, at the cost of American democracy. That’s what happened. Those are the facts.

If anything, we weren’t paranoid enough.

Yes, I think that was the lesson on January 6th.

Maria Bustillos is the founding editor of Popula, an alternative news and culture magazine. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, The New Yorker, Harper’s, and The Guardian.